A snapshot of Raqqa city (Edited by Enab Baladi)

Zeinab Masri|Ninar Khalifa

Before 2011, Hamrin Asa’ad and her husband, both born in Qamishli city, could not have property of their own, even their families’ real properties were registered in the names of other citizens. Why? The couple was deprived of this basic right because they were ethnically born Kurdish and were denied the Syrian citizenship under the Special Census of 1962.

Harmin and her husband, like many other Kurds, were stateless and legally classified ajanib (foreigners) in al-Hasakah governorate.

In 2011, the Syrian government passed Decree No. 49. Hamrin, her husband, and both their family members were granted the Syrian citizenship. She and her husband could finally establish ownership over the houses they owned.

Today, and though a Syrian citizen, Hamrin cannot transfer property rights to her children. All three of her sons are legally labeled maktumeen (unregistered)—children or grandchildren of foreigners—and are thus denied the right to property ownership.

In the eyes of the Syrian law, Hamrin’s three sons do not exist, with dozens of hundred other children like them who were forced into the maktumeen category for a variety of reasons, historical or arising from the decade-long war in Syria.

In the past ten years, the category maktumeen expanded beyond its original boundaries. Today, this tag is not exclusively used to refer to Syrian-born Kurds left stateless by the census. The category also includes unregistered children in opposition-held areas, where parents failed to establish lineage or document births in civil registration departments of the Syrian regime, deterred by political, security, economic, and even social reasons.

Of all the adverse impacts of the maktumeen tag, legal ones remain the harshest. These children continue to live outside the law, nonexistent and unrecognized. They are, accordingly, deprived of rights that citizens are allowed access to, including entitlements to ownership and inheritance.

In this extensive article, Enab Baladi discusses with a group of Syrian legal professionals the mechanisms needed to safeguard the rights of maktumeen Syrians to ownership and inheritance, particularly as laws that regulate civilians’ lives vary from region to region, contingent on parties holding reins to power throughout the country.

Hamrin got married in 1995; she was 18 years old. When she and her husband were granted the Syrian citizenship in 2011, they still could not register their marriage. The couple failed to proceed with the marriage registration procedure because in the family booklet Hamrin’s birthdate was documented as in 1986—nine years after her true birthdate and indicating that she got married while yet a little girl. This prompted the civil registration department to dismiss the registration application.

Harmin told Enab Baladi that she is not certain whose fault this was. It was either the mukhtar (leader of the neighborhood) or the civil registry employee that got her birthdate wrong. Regardless of whom to blame for the mistake, Sharia courts refused to register her marriage. “It is nonsense. I absolutely did not get married at the age of nine. My older son was born in 1996.”

Hamrin added that she also failed to correct the birthdate in the civil registration department’s records because the department dismissed the application she submitted and refused to respond to her husband and family’s repeated pleas. Consequently, she and her husband were granted the Syrian citizenship, but not her three sons, who were robbed of their right to establish ownership over any of the properties their parents had.

Harmin did not give up and searched for a way to register her marriage and births of her sons. The civil registration department and her lawyer advised her to file a lawsuit against her father, claiming he was the person responsible for the registered erroneous birthdate.

However, even if she consented to sue her father, the case might remain pending for a long time because her father has been a refugee in Europe for nine years.

At the end of her interview with Ena Baladi, Harmin was desperate, lost for a way out of this deadlock, while torn apart by the pangs of guilt, for her father would be arrested should he set foot in the country, while her sons deserved to be compensated for the suffering they experienced, and still experience, particularly that they are not children anymore. Her older son is 25 years old, married, and a father of a little boy.

| Legislative Decree No. 93,

It was passed on 23 August 1962 and ordered a special census, exclusively in al-Hasakah governorate, northeastern Syria, which is considered the center for the Syrian Kurdish minority. In a 2019 report— “Syrian Citizenship Disappeared: How the 1962 Census destroyed stateless Kurds’ lives and identities”— Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ) discussed the decree, its enforcement, and its legal implications on Syrian Kurds. The decree states in its Article 1: A general census is to be carried out in al-Hasakah governorate in one single day. The exact date will be more closely determined by an order from the Ministry of Planning, at the recommendation of the Interior Minister. In order not to lose their Syrian citizenship, the al-Hasakah Kurds had to prove residency in Syrian territory since 1945, at least. The extremely short time frame for the census – one day – set by the government was not enough for people to prepare the required documents or even to understand what was going on. The responsible authorities did not provide sufficient information about the census’ procedures and aims. Following the onset of peaceful protests in Syria, which demanded sweeping reforms in the country, Decree No. 49 was issued on 7 April 2011, granting Syrian Arab nationality to those registered as ajanib in al-Hasakah. |

According to the Civil Status Law, promulgated under Legislative Decree No. 26 of 2007, a maktum is— anyone whose father or both parents are registered with the Syrian civil registration departments or anyone with Syrian origin— who was not registered within the deadline stipulated by the civil registration departments; namely, within 30 days from the birthdate.

An informed Damascus-based lawyer told Enab Baladi that the key entitlement maktumeen are denied is their right to property ownership, which they might access through inheritance.

He added that the proceedings of settlement of succession and transfer of ownership both rely on the records of the civil status departments. Accordingly, maktumeen, whose names are not listed in the records of these departments, would not be allowed to initiate any of these proceedings, which deprives them of their right to concerned properties.

The lawyer added that the larger percentage of matktumeen today are children born to parents who married outside Syria and were not registered with the Syrian civil registration departments. Article 28 of the Civil Status Laws stipulates that birth cannot be registered unless the marriage of parents is registered first.

The Legal Committee, formed by Administrative Order No. 5380 dated 17 June 2007, states that marriage rulings issued in foreign countries, whether by a civil department or an Islamic center, are not applicable in Syria. To document a marriage in Syria, couples must take the necessary Syrian legal measures. Parents should first file a suit at the Sharia or spiritual court to establish their marriage, and then register the births of their children.

The inability to follow these processes by many Syrians living outside the country, for financial reasons or otherwise, has exacerbated the problem of maktumeen and deprived them of any future property rights, particularly because the registration of marriages and births with the civil or personal status departments in countries of residence or where parents have sought asylum does not exactly mean that marriages and births will be automatically registered with concerned Syrian departments. Parents have to go through the complex set of measures stipulated by Syrian laws.

The lawyer told Enab Baladi that this major challenge, encountered mostly by Syrians living abroad, cannot be practically overcome unless the authorities of the Syrian regime show readiness to facilitate recording civil status incidents occurring outside Syria through Syrian embassies and consulates.

Syrian judge Riyad Ali, for his part, told Enab Baladi that the Syrian war has undoubtedly created a breeding ground for maktumeen. However, he added, the large number of persons classified thus can be evidently traced back to the period that followed the unfair special census of al-Hasakah in 1962.He added that the census was conducted over a single day and that persons who managed to register their names and the names of other family members with the civil registry and obtained all required identity documents still maintained the Syrian citizenship, while, unluckily, those who registered their names but failed to obtain documents were classified as ajanib in al-Hasakah—that is, registered but stateless.

Those who failed to even register their names were classified as maktumeen, left both stateless and unregistered. These, as an identification document, were granted a card by the mukhtar of the local area they resided in, which articulates their names and other personal information. The card, nonetheless, did not guarantee holders any of the simple rights recognized Syrian citizens enjoy. Maktumeen had to obtain a security permit to practice basic rights such as moving unrestricted between provinces or making hotel reservations in Syria.

Judge Ali noted that the majority of those classified as ajanib or maktumeen were Syrian Kurds.In 2011, Decree No 49 was passed providing for granting Syrian citizenship to the ajanib of the al-Hasakah governorate, excluding maktumeen, who continue to be stateless to date.Judge Ali added that the past 10 years have given rise to a large group of maktumeen in Syria, particularly as entire areas broke of the Syrian regime’s control.

The Syrian regime approached areas with the loyal or opponent criteria. It was thus keen on depriving opposition-held areas of all government services, including those provided by the civil registry and courts. Denial of these services resulted in larger numbers of maktumeen over the course of the war, for many parents did not have access to regime-run civil registration departments, while those in the opposition predominated areas were all inoperative.

Judge Ali said that many families refrained from seeking regime-held areas to register their children, fearing security prosecution and arrest, particularly since the Syrian regime considered everyone living in areas outside its sway a popular source of support for “terrorist militants”, and therefore they are all liable to be chased by its security services.

He added that maktumeen, because they do not have the Syrian citizenship and are unregistered, do exist physically, but not legally. Therefore, they are deprived of all rights, including the right to own property. He noted that those classified as Maktumeen of al-Hasakah governorate, since 1962, are incapable of registering their property in their names. Instead, they have been registering their real estates in the names of trusted relatives or friends.

Registering maktumeen with the civil status departments is the first step to preserving their right to ownership of property, inheritance of any of their parents’ properties, and transfer of real estate ownership at the wish of the parents. This applies to children of unestablished parentage born to a Syrian mother and a foreign fighter, a border crosser, in the Syrian territories controlled by the opposition, or children born to Syrian parents inside Syria or in countries of asylum around the world.

When the peaceful protests took a turn into armament, foreign fighters from across the world joined the ranks of the Syrian opposition forces, using noms de guerre. They withheld their real names and descent. Many fighters appeared calling themselves names such as Abu Aisha al-Tunisi and Abu Ahmed al-Masry. These were later known as cross-border fighters.

As they flocked into opposition areas and while their stay lengthened, many of these foreign fighters married Syrian women citizens with unofficial marriage contracts, unregistered with the state’s relevant departments.

Children born of these undocumented marriages, whether in Syria or in fathers’ countries of origin, remain unregistered in their parents’ countries or in Syria, for fathers either failed to return to their countries or were killed during battles. Consequently, these children are growing up without knowing their real descent and without having any ties to their extended families.

An informed Damascus-based lawyer told Enab Baladi that children born to a Syrian mother and a foreign fighter, especially the children of Islamic State (IS) fighters, are pressing the concerned authorities into an “insurmountable bind.” The only measure that a Syria-based mother can take in this case is to register her children with the civil registration department as born to an unknown father.

The lawyer added that these children will have access to neither of their rights, for a person is born twice, once at a natural birth, and once at the legal birth—namely, registration in the state records that grant them their civil rights.

For his part, judge Abdullah Abdul Salam, Minister of Justice in the Syrian Interim Government (SIG), said that registration proceedings applied in the “liberated” areas are identical to those stipulated by the Syrian Personal Status Law. He added that the SIG adopted the entire system of Syrian laws with reference to the 1950 Constitution. Accordingly, it is the Syrian law that is applied in this regard.

The judge told Enab Baladi that the marriage of Syrian women to combatant border crossers is registered only when the husband’s descent is legally established. Then, the children’s linage to the father is also established.

Marriages, however, are denied registration in the case of Syrian women married to legally unidentified foreigners. As a result, children too are denied registration in the areas north of Syria. The registration proceeding mandates that the father’s real name and descent be both legally established, with two witnesses that testify they are real.

Judge Abdul Salam added that the SIG is holding discussions with the Syrian Islamic Council and will soon hold a workshop with personal status judges “to find a solution to this dilemma because these children should not remain a burden on their communities.”

| Al-Laqīṭ (Foundling)

The administrative classification under which fall children abandoned by their parents for fear of financial burdens or social stigma and policing. The child, in this case, remains unidentified, without established parentage or a guardian. Maktum Is the administrative classification under which fall persons unregistered in the official state records. Persons of unrecognized parentage Is the classification under which the children’s linage is attributed to the mother, without any clues to the father’s identity. |

The informed lawyer told Enab Baladi that the situation of maktumeen born to Syrian parents is less problematic than those born to foreign fighters. These children can be registered in the areas held by the opposition and thus can have access to property transfers. The only factor that might complicate the situation, in this case, is the location of the property, namely when the parents’ properties are located within the regime-controlled areas.

In this case, it would be difficult to document births, and thus difficult to maintain their property and inheritance rights.

Commenting on the same group, judge and minister Abdul Salam said that “children, classified as maktumeen who are born to Syrian parents, are registered after marriage is duly confirmed in the personal status courts of SIG, even if the husband is missing or dead.”

He added that of core matters relating to establishing lineage is the issue of inheritance. In the majority of the “liberated” areas, there are no real estate records. He added that when such documents are available settlement of inheritance is established through Sharia-based proceedings when the property in question is owned by citizens themselves and through an administrative proceeding when the property is owned by the state and to which citizens have been granted the right of disposal.

He pointed out that people in the northern regions mostly prefer the sharia settlement— whereby the male shall have the share of two females—over the legal settlement which equates between male and female. Today, inheritance is divided, and the distribution of allocation is recognized by the hires themselves because there are not operative real property registration departments in the region.

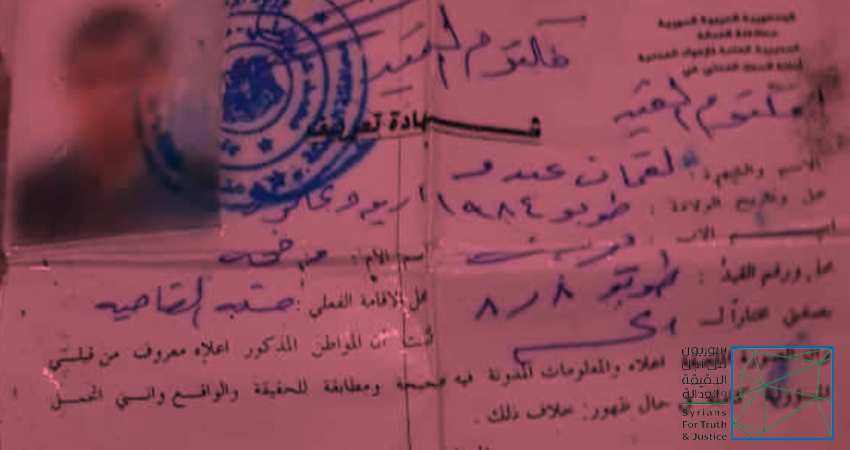

The identification document granted to Luqman Abdo, Kurdish Syrian classified as Maktum —(obtained from the witness Luqman Abdo by Syrians for Truth and Justice)

To discuss the maktumeen’s documentation of linage and access to property rights in the north-eastern regions of Syria, Enab Baladi spoke to a judge working in the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES) departments. Wishing that his name be withheld for security reasons, the judge said that the administration is applying the Civil Status Law enforced since the 1950s.In the areas held by the AANES, affiliate offices, directorates and judicial departments oversee real estate transactions and related lawsuits.

Even though the AANES has been enforcing the Syrian Civil Status Law in the documentation of marriages and registration of maktumeen children born to Syrian parents, its affiliated Social Justice Council prevents offices of justice in northeastern Syria from addressing actions in rem.

The council requires the dismissal of all in rem lawsuits, regardless of the stage they are in and no matter what rights they are seeking to determine— disposition, usufruct, documentation and certification of sales contracts, or even establishing a parallel (informal) real estate registry.

In the AANES areas, real estate lawsuit judgments are put to force by the Land Registry. However, currently, court orders are impossible to execute since there are no active land Registry offices in the region. Such executive and registration restrictions apply to property transactions of maktumeen even after they are registered with the civil registration department.

A large segment of Syrian families is facing major identity issues, relating to lacking identification or property ownership documents, which they lost and/or were unable to obtain because they failed to record their civil events— births, marriages, and deaths—with the official civil registration departments, prevented by displacement circumstances, the fact that many areas are outside the control of the Syrian regime, the destruction or closure of civil registration departments, that remained operative, along with courts, only in regime-held areas.

The Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) stated that 70 percent of Syrian refugees lack basic identity documents.

The NRC interviewed 734 internally displaced families in areas administratively affiliated to the governorates of Daraa and Quneitra. Half of the interviewees said that “their marriage documents were lost, confiscated, destroyed or left behind when they were displaced.”

The NRC added that, in the same sample of interviewees, a quarter of each family’s members, mostly above 14, do not hold the national identification document though they are at the legal age to obtain it.

The NRC also addressed the status of children of the families interviewed. It found out that out of 675, under the age of five, 304 are unregistered in the family booklet, a document that families need to obtain other essential documents, and 195 do not have an official birth certificate, except for the certificates issued by departments run by the de facto authorities and which official departments do not recognize. This lack of documents threatens a large number of these children with statelessness.

The state obliges male and female citizens to document all civil status events, including births, deaths, marriages, divorces.

Failure or inability to register births costs newborns their legal identity, political and civil rights, such as the right to vote or run for elections. Loss of legal identity lays the ground for a multi-fold deprivation, such as deprivation of rights to education, healthcare, property ownership and legal work conditions, in addition to deprivation of freedom of movement, obtaining a passport, as well as officially documenting a marriage, establishing children lineage, divorce, or death.

The loss of legal identity also has a bearing on a person’s social position, for children of unknown parentage too often suffer from societal discrimination, in addition to protection implications that women, wives and mothers endure, as they get denied, not only rights but also protection guaranteed by the law.

Lacking any of the documents above has extremely complex consequences on the life of households run by women, whose husbands are arrested or forcibly disappeared. These women are usually denied their husbands’ death certificates which adversely affects their handling of legal matters relating to the deaths of their husbands, and thus, the registration of their children. Such women cannot travel with their children and have to battle over property rights, including inheritance, ownership, housing and using a piece of land.

To circumvent these implications many women were forced to have their husbands officially declared dead, when they have been absent for four years, or claim that they have abandoned them when they have been missing for a year. To do this, women rely on Article 109 —separation for absenteeism—of the Personal Status Law, which says that a woman is entitled to resort to the court to obtain a separation ruling four years after the husband was missing. The woman can pursue this procedure after the husband’s absence for three years without an acceptable excuse or due to serving a sentence in prison of over three years, even if that husband has money the women can spend.

The Syrian Nationality Law provides mothers with an opening to save children of unknown parentage from statelessness. Article 3-B of Legislative Decree No 276 of 1969, states that children born in Syria to Syrian Arab mothers, whose linage to the father has not been legally established, can be granted the mother’s nationality. This right also applies to children born outside marriage or in cases of rape. However, social stigma has been a major barrier to using this legal text.

Undocumented marriages impose other challenges to the mother and jeopardize her right to legal guardianship of children. Article 167-2 of the Personal Status Law (amended) grants mothers access to this right only when she is legally assigned a guardian by the father, for overseeing the assets of minors after the father’s death is delegated to the guardian chosen by the father, even if that guardian is not a close relative to the children.

Court proceedings, which offer women a solution to access their own rights and those of their children, have been adding an extra layer to concerned women and children’s suffering.

Lawsuits filed to the courts to get a separation ruling are proceeding slowly, even when the men involved have already been documented dead. This legal stalemate is due to the increasing number of lawsuits filed for establishing common-law marriage and the security approvals demanded for all applications filed to the court, including applications to document divorce, death, burial, sale, property purchase and rent.

According to an investigation conducted in cooperation with the office of the first Sharia judge in Damascus, requests for administrative marriage confirmation increased ten times in 2015 (10,504 applications) compared to 2009 (719 applications).

In addition to pressure on the courts, the costs of marriage documentation procedures are adding to the women’s financial burdens, particularly those married by common-law contracts and whose husbands are either dead or have been missing. The extravagant costs are also giving rise to extortion and increasing corruption which has been preventing families, women in particular, from registering events with the civil registration departments.

There are no official statistics as to the exact number of maktummen in the areas outside the Syrian regime’s control, whether those born to identified parents but were unregistered or born to women married or forcibly wedded to legally unidentified fathers, such as foreign combatants. However, the Who Is Your Husband campaign documented that there are 1826 children of unknown parentage in Idlib and its countryside, the northern and western Hama countryside, who were born to 1124 undocumented marriages out of 1735 marriages monitored in the area. In said areas, women refrain from filing lawsuits to document their marriages fearing accountability, particularly those married to IS fighters.

Though it seems that a long path lies ahead of authorities concerned with affairs of maktumeen and their rights to property ownership, a solution can be based on the following steps:

-Raising awareness on the importance of registering marriages with the civil registration departments;

-Providing Syrians with access to an effective, swift, and sustainable mechanism to register civil status events;

-Prioritizing the interests of children and their rights;-Collecting and preserving property ownership documents;-

Eliminating legal discrimination against Syrian women;

– Urging courts to speed up issuing a ruling in cases related to families’ affairs;-Encouraging Syrian lawyers to volunteer to represent women, particularly displaced and refugees, filing applications to document marriages and lineage;

-Demanding the release of detainees and forcibly disappeared, including, children, women, and men;

-Reinforcing international standards on preventing and reducing statelessness, a status that facilitates the involved persons’ loss of protection, security, and dignity.

if you think the article contain wrong information or you have additional details Send Correction