Saleh Malas| Zeinab Masri | Amal Rantesi

Since the Chilean military commander Augusto Pinochet was arrested in London in 1998, the human rights community in Latin America has been making unrivalled efforts to combat the impunity of perpetrators of human rights violations, seeking to prosecute militants and politicians involved in Operation Condor, hold them to account, and subject them to established penalties.

Condor—a large-scale political repression operation— involved the assassination of opponents in exile, arbitrary detention, and enforced disappearance.

In a research paper titled “Remnants of Truth: The Role of Archives in Human Rights Trials for Operation Condor“, Latin American human rights activist, Francesca Lessa, argues that one key source of evidence used in the trials of the Condor violations’ perpetrators was archival records, which offered a reading of the investigated crimes by linking the clues they contained to the context of trials held. This one incident helped archives overcome the thorny issue of relevance and turned them into an authoritative piece of evidence in accountability proceedings.

Vested with a functional responsibility towards human rights, these archival records assisted in the prosecution of perpetrators through recounting the political activities of the victims and demonstrating the mechanism middle-ranking officers adopted to suppress them. Consequently, archives became crucial to the transitional justice phase in Latin America, according to the research.

Political repression practiced by dictatorships in Syria and Latin America is not very dissimilar. However, repression in Syria took an excessive course after 2011 when the Syrian regime used chemical weapons to oppress its civilian opponents, some of whom struggled to catch their breath.

On 2 March, a group of chemical attack survivors and rights groups—the Syrian Center for Media and Freedom of Expression (SCM), with the support of the Open Society Justice Initiative (OSJI) and the Syrian Archive—filed a complaint in France, asking prosecutors to probe the August 2013 chemical attacks in Douma and the Damascus suburb of Eastern Ghouta.

Within the scope of evidence and data science, events of the past do not have an objective existence unless they are engraved in human memory and preserved in archives. That is, violations committed in the past are only those which exist through intersectional combinations of survivors’ accounts and archives documenting them.

In this extensive article, Enab Baladi interviews Syrian human rights defenders, legal professionals, and activists, discussing efforts aimed at archiving the history of the Syrian conflict and crimes against humanity committed over a decade, as well as the difficulties facing these efforts.

Enab Baladi also sheds light on the role of archives in providing evidence that human rights organizations or governments may legally rely on to hold accountable the perpetrators of human rights violations inside Syria that never stopped since the beginning of the 2011 protests and during the shift from peaceful demands to armed violence.

Institutional activism watching over Syrian memory

In June 2020, a group of Syrian activists launched a campaign entitled “Facebook is fighting the Syrian revolution.” The campaign was organized after the social networking service company shut down accounts documenting what is happening in Syria, alleging they violated its heavily regulated content policies, updated with a new list of banned words relating to the Syrian revolution. These words fall under the tag of incitement to “violence and terrorism,” reported Anadolu Agency at the time.

In a June 2019 OP-ED, “How Facebook’s sudden change hinders human rights investigations,” Amnesty International denounced the changes applied by social media platforms to search tools that aid the human rights community document violations, in addition to removal of content and videos uploaded on these platforms by Syrian activists in hope of final accountability.

The OP-ED stressed that the platforms are dropping or changing search functions without any consultation with human rights investigators. These sudden changes do not foster “trust” in these platform’s claims that they support human rights and will hamper concerned organizations’ activities in this regard.

One of these sudden and unannounced changes was undertaken by Facebook. The platform turned off the Graph Search tool, which could lead to “disastrous results.”

“Graph Search is a Facebook tool that allowed investigators to find the publicly available content that otherwise would be buried – much like a needle in a haystack,” Amnesty described the function of the tool and the impact of its deactivation.

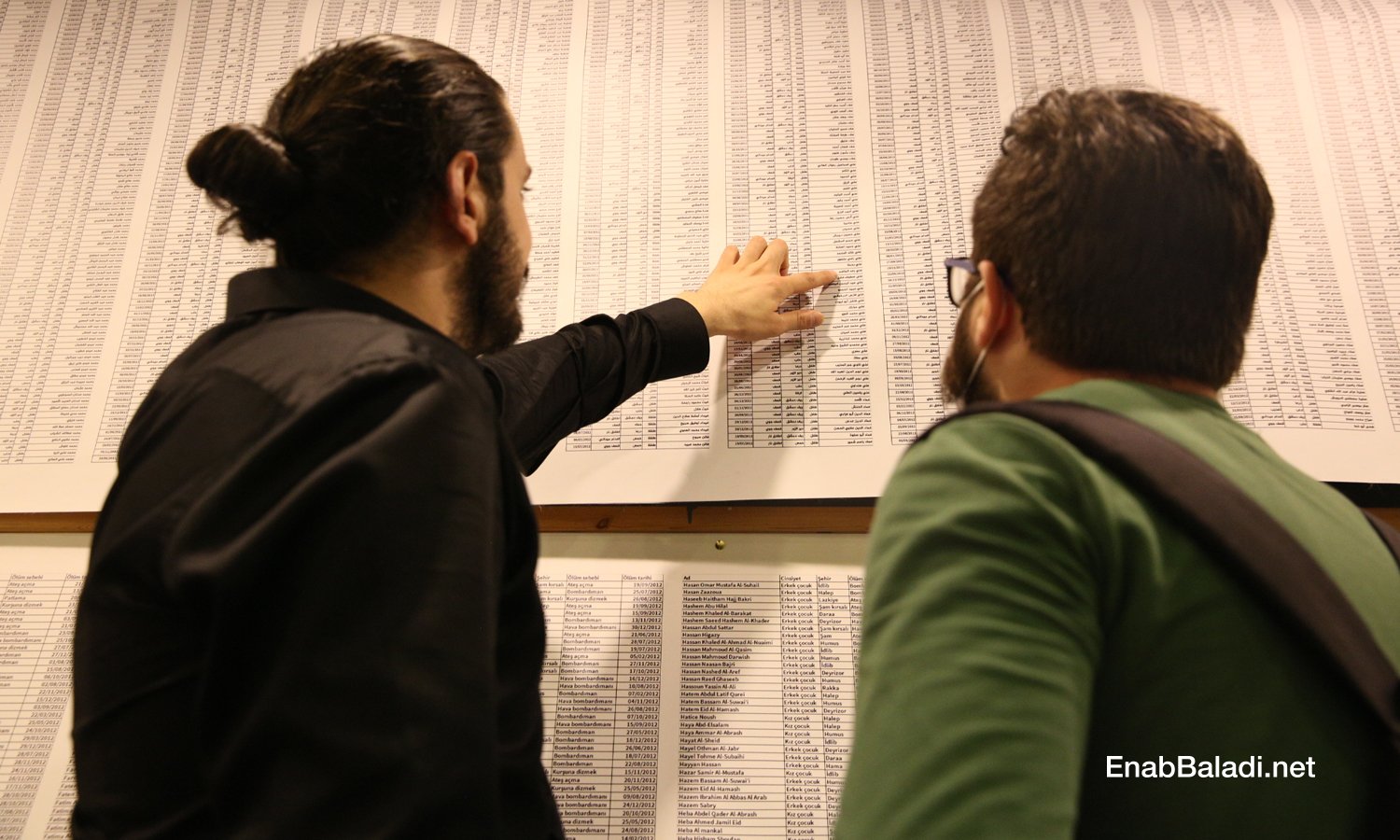

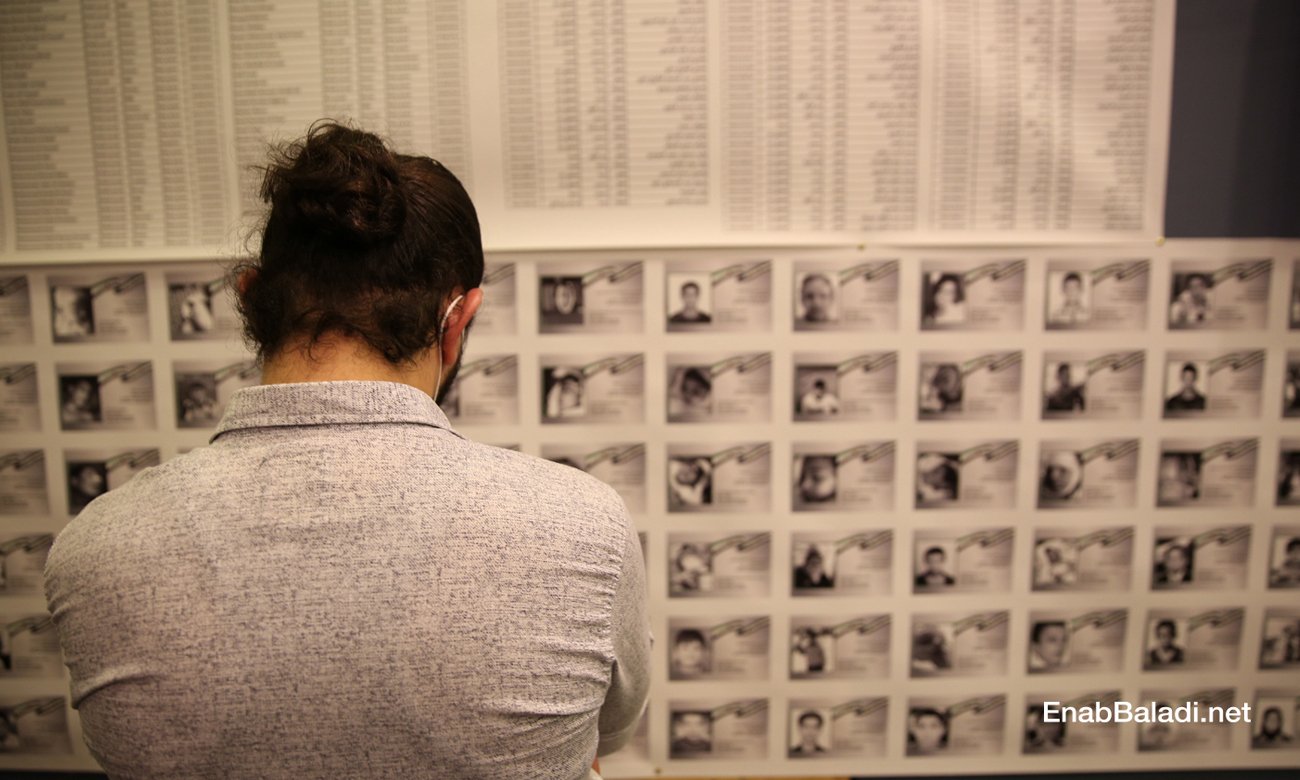

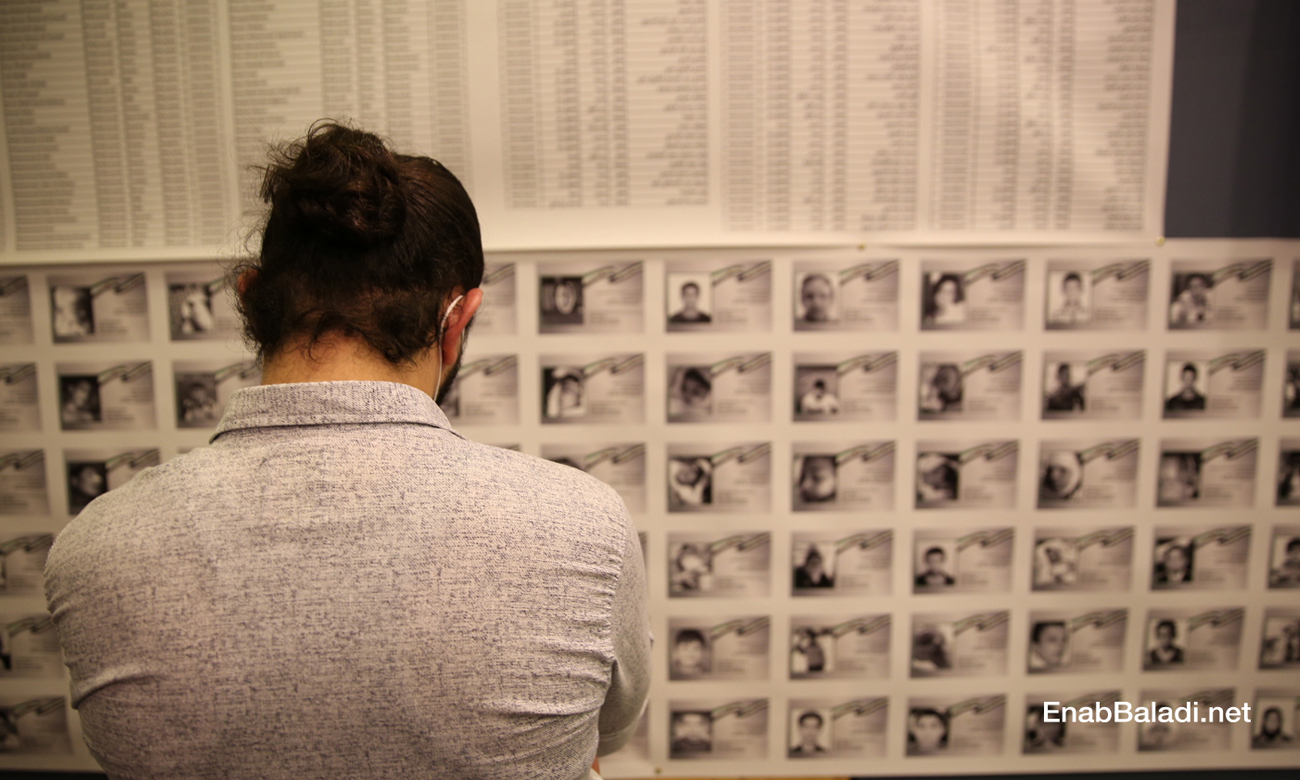

Residents of Memory photo exhibition, displaying thousands of pictures of child victims killed after 2011, organized by the Syrian activist Tamer Turkmane in Istanbul – 13 October 2020 (Enab Baladi/ Abdulmuin Humus)

Amnesty added that “This is not the first time a social media company has betrayed the human rights community. In mid-2017, under pressure from governments to remove content that could depict or glorify terrorism, YouTube started removing masses of videos from Syria from its platform.”

Listing another unjustified change, Amnesty referred to the removal of the Panoramio in 2018. The organization called Google Earth’s deactivation of the tool “a blow to the human rights community,” depriving it of “an amazing resource.”

“Integrated into Google Earth Pro (one of two tools every human rights investigator using content online should have),” it gave human rights researchers access to massive content on the Internet.

Offering them a time capsule that connects them with the past, through Panoramio, “researchers could look back at holiday pictures online from people who had visited, say, Aleppo before 2010, or parts of Nigeria and Cameroon now engulfed in conflict.”

The tool came to the organization’s help “in the time-consuming work of establishing where a video of an airstrike had been filmed, where a torture scene took place, or where a trafficking victim was last seen.”

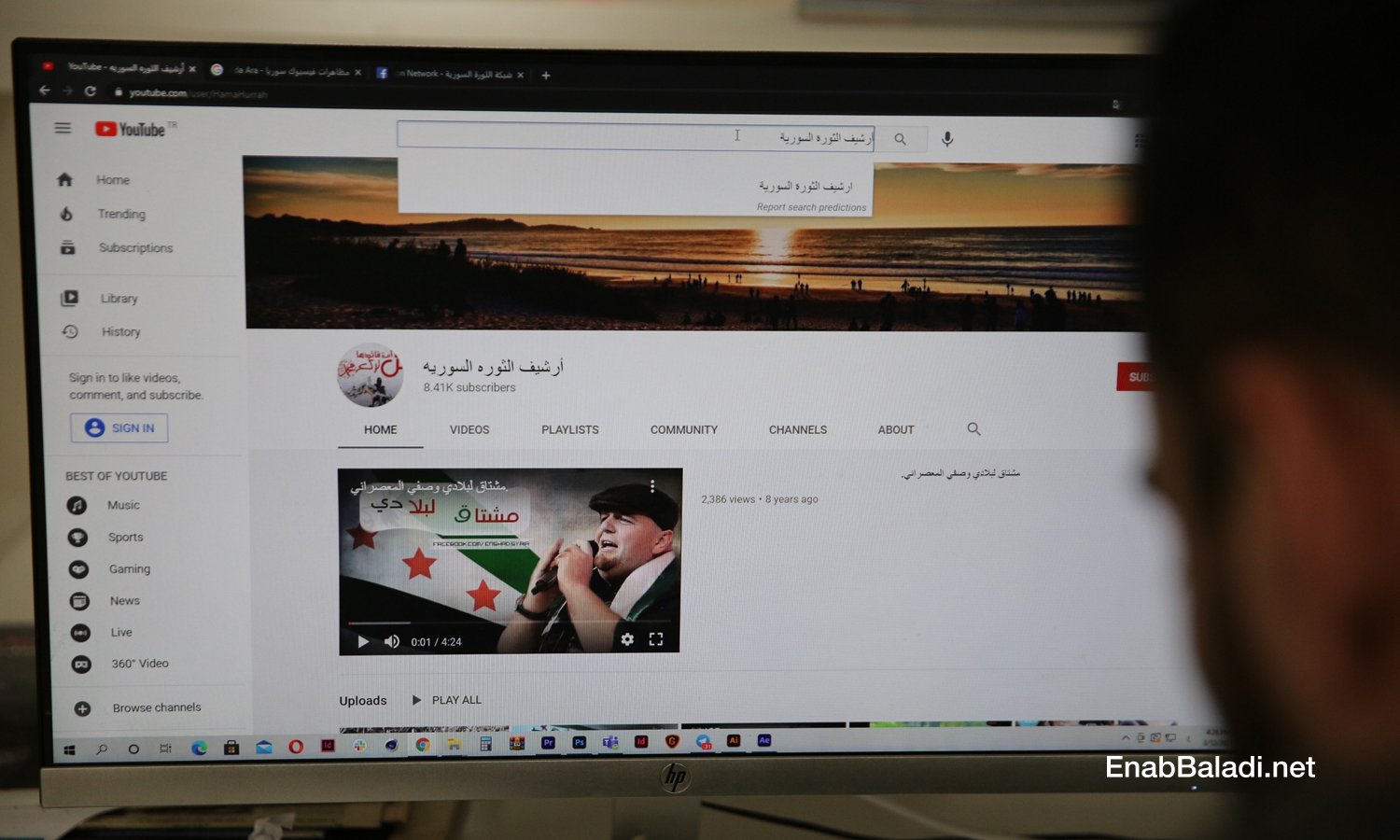

In September 2019, the Syrian Archive—a Berlin-based NGO established to profile the crimes of the Syrian conflict— posted a statement on its Facebook page. It said that YouTube shut down the channels run by Ugarit and Sham media agencies. The channels archived a mass of 300,000 videos, all lost today.

Fortunately, the Archive said it had a backup version of the two channels’ removed videos. It also called on Syrian content contributors, makers, and owners of visual materials related to Syria to send these materials for archiving.

The Syrian Archive defines itself as a project of Mnemonic, a non-profit organization dedicated to archiving disappearing digital material.

The organization launched a campaign— Lost and Found— to restore removed content that aimed at “re-humanizing the Syrian digital memory” and succeeded in retrieving and reuploading 350,375 videos onto social media platforms.

Syria Archive’s Campaigning and Advocacy Officer, Mohammed Abdullah, told Enab Baladi that the organization also works on collecting, categorizing, and analyzing visual evidence of human rights violations across Syria, in addition to archiving the compiled data into a digital memory and establishing a verified database of human rights abuses.

Challenges

Abdullah added that the organization reacts to the significant documentation content that disappeared from the Internet. The organization, he said, assists in preserving or restating content, in addition to its endeavor to be one of the tools that contribute to achieving justice and promoting accountability.

According to Abdullah, such Syrian archiving initiatives are prominent because a mass of documented data was either lost or got corrupted, while remaining data could turn into future evidence of the historic narrative, or into evidence that helps in building a legal case or pushing action towards accountability.

One major challenge to documentation and archiving efforts has been loss, particularly the removal of content uploaded onto social media platforms and other publishing channels, which shut down many users’ accounts.

Another challenge, that pertained to the early stages of the archiving process, originated from the adopted documentation method. Organizations working on the issue sometimes lack documentation and verification tools, not to mention the voluminous visual content recording what happened in Syria over the past decade. The vastness of materials makes it “extremely difficult” for concerned organizations to document and archive data given their limited resources, Abdullah added.

How does the Syrian Archive work?

The Syrian Archive’s team collects videos and footage available on the Internet, which are archived and then subjected to various levels of verification, specific to the incident documented.

Once archived, videos and footage are checked against other available materials to ensure the content is veracious and confirm the date of filming. The team then reaches out to relevant sources, including field journalists and activists, as well as active humanitarian organizations to investigate into certain incidents.

The team also incorporates digital verification tools, such as satellite images and functions that define dates and identify shades, in addition to tracking flights and verifying victims’ identities.

Abdullah told Enab Baladi that the Syrian Archive follows an innovative methodology. The organization’s approach involves several attack-related indicators, which help the team categorize attacks as deliberate or not. The approach also involves establishing a database of the documented information, conducting a probe into each separate case, and aggregating findings. This process enables the team to analyze patterns and trends that appear in the finalized database, published on the Archive’s website.

Individuals fighting to save data from potential loss

Archiving and documenting the history of the Syrian conflict is not limited to institutionalized initiatives and teams. Individuals also have ventured out to save Syria-related content from loss, and voluntarily. One such individual is the Syrian activist Tamer Turkmane.

Tamer recounted to Enab Baldi how his documentation endeavor began. Starting in 2014, he dedicated his work to documenting the identities of victims of violations in Syria. Under the name of each victim, he attached a picture and a video, with all the information available on the person featured.

In late 2016, Tamer noticed that a mass of videos was being removed by YouTube, all documented the stories of victims of human rights violations. He embarked on another hunt, downloading all the videos he could from the jeopardized channels.

Tamer called his work “duty”, adding that the “disaster” for which the removal of videos by YouTube stands cannot be ignored. “These materials are essential to writing an authentic account of history and holding perpetrators accountable in the future.”

He added that the removal of videos “might lead to repeating the same mistakes committed during the 1980s massacre of Hama city. Back then there was nothing such as documentation.”

He believes that the core of the documentation process is collecting, categorizing, and preparing data for writing history or effectively bringing all perpetrators of human rights abuses to account.

Tamer told Enab Baladi that he documented over 2.4 million videos since 2011, in addition to about 100,000 articles published by varied Syrian media outlets. In addition to citing the names of publishers, Tamer arranged articles chronologically, to relate incidents to their reported dates.

Tamer also archived 400 books addressing the events that Syria has been experiencing since 2011. He provides a PDF version of the books to make them accessible to people who cannot afford to buy them, citing the date of publishing and adding a briefing of the content.

He also compiled about 2000 researcher papers and reports covering human rights issues and the violations committed in Syria. This content is published by a large number of Syrian and international organizations specialized in documenting violations.

He documented the deaths of about 250,000 Syrians, under tags of death date, birthplace, death method, and perpetrators, in addition to several other files documented “properly” and stored in a “safe place.”

As he continues to work independently, Tamer’s documentation efforts are challenged mainly by lacking long-term funding. He told Enab Baladi that “All the money he gets is from friends. These sums fail to answer the magnificent financial need, covering only simple logistics.”

The “Residents of Memory” photo exhibition, displaying thousands of pictures of child victims killed after 2011, organized by the Syrian activist Tamer Turkmane in Istanbul – 13 October 2020 (Enab Baladi/Abdulmuin Humus).

Archives in the context of human rights

The aims of archiving histories or armed conflicts are consistent with the set of principles devoted to protecting and promoting human rights, for archives are essential to the ability of victims to realize their right to the truth, based on accurate and verified information, to using archives in criminal accountability processes, and using archives in non-judicial truth-seeking processes.

States and individuals use archive-based approaches to address past large-scale violations of international human rights law and international humanitarian law, and to reduce the possibility that such violations will recur.

Archives are crucial to the exercise of a set of individual rights “such as the rehabilitation of people convicted on political grounds,” and families’ rights including “know[ing] where their missing relatives are, and the right of political prisoners to amnesty.”

Archives enable nations to exercise “their right to an undistorted written record, and the right of each people to know the truth about its past.”

Post-2011 archiving initiatives

The Syrian Revolution Archive: an individual’s project

The Syrian activist Tamer Turkmane defines the initiative as an archiving project that seeks to preserve all post-2011 documents relating to the Syrian revolution.

Syrian Archive: using archives for advocacy and justice

Syrian activists and human rights defenders founded the project in 2016. It is led by the Syrian journalist Hadi al-Khatib.

On the official website, founders define the archive as a Syrian-led project that aims to preserve, enhance and memorialize documentation of human rights violations and other crimes committed by all parties to conflict in Syria for use in advocacy, justice, and accountability.

Syrian Prints Archive: all prints available on one website

Syrian Prints Archive is an independent project that works on archiving periodic prints issued inside and outside Syria since the outbreak of the March 2011 Revolution. The archive’s team, an offshoot of Enab Baladi newspaper’s core team, started the project in 2013. The team obtains links to materials published by Syrian newspapers and reposts them on a weekly basis.

Since 2011, a large number of Syrian outlets—issuing magazines, newspapers, and periodicals—emerged, amounting to over 200 platforms in late 2014. Many of these outlets are inoperative today.

The official launch of the beta-version of the website was on Nov. 21st, 2014, during the first Conference of Syrian Journalists Association in Gaziantep, sponsored by NPA.

Syrian Oral History Archive: to document experiences of victims

The oral archive is a pilot project implemented by Dawlaty and Women Now. With the project, the two founding organizations seek to build the capacities of Syrians, youth in particular, to engage them in the democratic shift and transitional justice process in Syria.

The archive documents the experience of a large segment of Syrians who have been affected by the conflict.

According to Dawlaty, the archive’s short-term goal is answering the people’s needs and raising their voice when it comes to human rights violations, as well as shedding light on the affairs and struggles of persons subjected to arrest or enforced disappearance.

The compiled data will be invested in advocacy efforts, planning development projects, and setting up international policies.

As for the long-term goal, the archive will be a means to establish a network of operative civil society organizations (CSOs) to unify all memory-oriented projects in Syria and better guide post-conflict mechanisms.

The archive’s methodology is hinged on three independent and interconnected processes: collecting oral history, building an archive, and developing programs related to transitional justice, advocacy, and community participation.

Creative Memory of the Syrian Revolution: Navigating the “ingenuity space”

Founders define the project’s aim as “to document all forms of intellectual expression, both artistic and cultural, during the time of the revolution, by writing, recording, and collecting stories of the Syrian people, and the experiences through which they have regained meaning of their social, political, and cultural lives.”

The archive’s prominence lies in being a platform that collects intellectual, artistic, and popular culture products in one specialized place, facilitating access to this massive content, presented in Arabic, English, and French.

The website also aims to “enhance the impact of the artistic Syrian resistance, to reinforce its place in the revolution, to archive and spread the messages it expresses, and to help establish networks between the groups or the individuals who animate it, as well as links with the outside world.”

Founders of the website believe that they are contributing, one way or another, to writing their own modern history, for “the work on the website aims to build an archive of national intangible heritage; to protect it is essential, as it belongs to the collective memory, and is a duty to protect it to give back to the Syrian people its history and all its historical wealth, and to make it proud of this present history.”

The content available on the website is collected from Facebook pages and other platforms on the Internet, aggregated into 22 distinct creative and artistic categories.

Digital Syria: dedicated to cultural heritage

According to its website, the initiative “is dedicated to the tangible and intangible cultural heritage of Syria and the Syrian people. Launched in 2019, Digital Syria combines online resources with international events, publications, and educational programming.”

“Launched in 2019, Digital Syria combines online resources with international events, publications, and educational programming.”

Addressing the past legally

Archives would not be the overwhelming evidence

International treaties recognize the importance of archives kept of armed conflicts. The Report of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on the seminar on experiences of archives as a means to guarantee the right to the truth points to the measures that should be taken to place each archive center under the responsibility of a specially designated office, adding that:

“In countries where national archives are weak or the public does not have confidence in them, it may be necessary to establish transitional records centers, where the entire archives of a repressive entity are preserved and there is accountability for the continuous chain of custody of those archives.”

Archival records and oral history are key parts of the transitional justice phase. Both forms of recorded history help in bringing perpetrators to trial. Therefore, plaintiffs and the human rights community must have regular access to these records.

Archival records of human rights violations were used in prosecutions in Argentina, Guatemala, and Spain, while in Chile they were essential for the work of investigative commissions.

In the Syrian context, whether archives, that concerned Syrian organizations are working on now, will be adopted as the only legal grounds for starting a process of accountability or not will remain debatable, Hussam al-Qatlabi, Syrian human rights defender and human rights violations archivist, told Enab Baladi.

Working on human rights violations, pertaining to International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights Law, al-Qatlabi added that an initial answer to this debate would be in the negative. The role of such archiving initiatives will be mostly disregarded when it comes to the process of criminal accountability of human rights violations in Syria.

“The judiciary would not legally embrace such records for a variety of considerations,” al-Qatlabi said. One of which is related to the nature of the visual archive created by Syrian organizations and the nature of the Syria-linked visual content on the Internet in general. With nature, he referred to the fact that available materials were filmed, uploaded, and classified without adhering to criteria and taking an account of basic elements mandatory when documenting these types of crime in Syria.

According to al-Qatlabi, two basic elements must be available to have archival records that can be used as legal grounds. These are the credibility of the material collected and their relevance to the criminal case pursued.

These two elements are essential because the second party to the lawsuit—namely, prosecuted perpetrators—can always build an argument on these two prerequisites, which remain difficult to meet under the judicial and criminal standards that governed the processes of filming, collecting, and aggregating these materials over the past a few years.

Al-Qatlabi said that “The chief purpose of individual cameras during the Syrian revolution was advocacy, media coverage, and conveying a picture of what is happening, particularly after the Syrian regime closed the country to international media and institutions, and committed a collective massacre against Syrians.”

In Syria, executive authorities hold reins to the press and the media through the Ministry of Information, press laws, and administrative decrees. It is the reason why journalists and media outlets could not have access to what happened inside Syria when protests against the regime erupted in 2011.

However, it is difficult to turn a blind eye to the huge amount of archived visual and written materials. The Syrian conflict, according to al-Qatlabi, is so far the most documented conflict in history. “This is a thing that no party can simply overlook and shrug off,” particularly since accountability is often sought in countries where the public prosecutor, the investigation, and judicial teams are not totally familiar with the Syrian context and the relevant details of the conflict. Therefore, these authorities are in a dire need to learn and understand the environment and the context outside the narrow framework of texts and laws.

At best, al-Qatlabi said, the huge volume of the archived data may contribute to strengthening the elements of reliability and relevance provided by these visual and written materials, used to prove a pattern or the system underlying the committed violations investigated by the competent police and the public prosecutors.

He, however, reiterated that “The visual Syrian archive will not be considered a legal document, except in very rare cases that cannot be treated as references.”

Proof that judiciary cannot exclude

European courts do not exclude any evidence, which could be cross-checked with other documents on the violations subjected to a criminal investigation, Joumana Seif, Syrian lawyer and fellow researcher in the International Crimes and Accountability Program at the European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights, told Enab Baladi.

Seif added that investigation teams specialized in probing “war crimes” build the case by restoring to a wide range of evidence, such as photographs, voice records, witness accounts obtained from victims of the violation, and their families. They utilize any proof relating to corroborating the violation under trial or the indictment against the accused in a specific case or complaint.

The court and the public prosecutor are entitled to examine the evidence file, evaluate it, and verify its authenticity, and then make the decision to accept or refuse the file as evidence of the violation.

According to al- Qatlabi, there are several caveats regarding incorporating archival records in the process of litigation. Such records, he said, may support the case and may as well thwart it should providers of the records be unable to prove their authenticity. Furthermore, in some cases, the same materials may be used as a counter-argument against the plaintiffs themselves.

if you think the article contain wrong information or you have additional details Send Correction

النسخة العربية من المقال

-

Follow us :

Most viewed

- Potential Erdoğan-Assad meeting in Moscow: Talks of excluding Iran

- European countries call for re-evaluation of policy towards Syria

- After Turkey and the opposition, SDF shows willingness to dialogue with Syrian regime

- Al-Assad reproduces Constitutional Committee through People's Assembly

- After al-Hasakah, AANES releases prisoners in Raqqa

A

A

A

A

A

A

More In-Depth

More In-Depth