Ali Darwish | Nour al-Din Ramadan | Habaa Shehadeh

In late 2019, Abdulfattah and his family were forced to leave their village, al-Hawash, in al-Ghab Plain. His escape was urgent. In addition to identity documents, he packed only a few lightweight belongings, leaving behind his land, his agricultural equipment, and all his crops. Since then, the farmer had no means to sustain himself and became dependent on aid distributed in a camp for internally displaced persons (IDPs) in Idlib province.

This is not the story of Abdulfattah Hayan only, for thousands of other families fell to the same situation. Some million people were coerced to abandon their lands in the suburbs north of Hama and south of Idlib as the Syrian regime forces and their allies advanced into the area. These people lost their homes, their stable lives, and their agricultural lands.

Such deprivation of agricultural land did affect not only farmers, who were robbed of their chief source of income but also the overall population. These lands provided the region with needed crops, particularly as the economic crisis continued to spiral, with the prices increasing rapidly and rates of both unemployment and poverty rising alarmingly.

The ceasefire, agreed to by guarantor countries nine months ago, had barely brought the region any stability or a promise that work would soon be resumed when COVID-19 hit, threatening the lives of its residents and imposing further restrictions on them, with internal and external crossings blocked.

In this investigation, Enab Baladi sheds light on the economic condition of the agricultural sector in northwest Syria and fathoms the various outcomes of losing over half of the arable lands in areas outside the regime’s control; the consequences of closing crossings, as suffered by both farmers and consumers; and the role of the two existing governments in providing support to the food industry.

Farmers no longer have their tools and crops

Abdulfattah Hayan owns a piece of land in the al-Ghab Plain. He does not keep the title deed to prove his ownership, but he holds a clear, detailed memory of the wheat, barley, alfalfa, peas, and beans that he planted earlier with his brothers. That was before he was forced to move to a different reality in a camp where he does not have enough space to live.

By cultivating his 50 acres, Hayan used to make 3000 to 3500 USD per year. However, this year he did not make a penny, nor was he able to plant. “Planting again requires many things that we lost in the displacement,” he told Enab Baladi.

The sheep market in Arshav town days before Eid al-Adha – 27 July 2020 (Enab Baladi/Abdussalam Majaan)

The loss of agricultural and watering equipment and the lack of financial resources have all prevented Hayan from practicing his profession. Worse yet, the market was deprived of his land productivity.

Farmers in northern Syria depend chiefly on winter crops due to the machinery shortage and the scarcity of irrigation water. Consequently, there has been a dearth of “strategic” crops in the region, Hayan said, such as olives, pistachios, figs, pomegranates, and vegetables that were common in the villages of northern Hama and southern Idlib.

Hayan sighs while explaining how farmers make a living today after they lost their lands. He said that many farmers turned to relief aid in the absence of job opportunities, took odd jobs, and some have even “partnered with locals and IDPs to cultivate fields with crops alien to the area.”

Others risked their lives to harvest their lands on active fronts with the Syrian regime forces, where mines and unexploded remnants of war are widely spread. A few other people took their livestock to the areas they were displaced to. They had to sell them due to the lack of broad areas of pastures and feedlots and livestock grazing’s overwhelming costs.

“Agricultural organizations and parties concerned with farmer affairs did not even imply compensation. There will be neither material nor moral compensation,” said Hayan, adding that there was not even an evaluation of the agricultural loss sustained in the region.

The Nors Center for Studies in northwestern Syria estimated that the area had lost about 3,140 km² since 27 August 2019, of which 60 percent of the agricultural lands were controlled by the opposition.

Despite the establishment of previous projects to support farmers in the region, the response to redress the greater damage that the agricultural sector suffered was limited to relief projects and government decisions whose economic results have not yet stabilized.

Several projects were dedicated to assisting the region’s farmers, but the response to the extensive harm suffered by the agricultural sector was limited to a few relief programs and government decisions that have not stabilized the area’s economy so far.

The sheep market in Arshav town days before Eid al-Adha – 27 July 2020 (Enab Baladi/Abdussalam Majaan)

Organizational mess and lacking supplies: People quit farming

In opposition-held areas in northern Syria, farmers encounter organizational problems and a lack of financial resources and agricultural machinery. Additionally, there are the high prices of fuel used for operating machinery and transportation; the continuous decline of the value of the Syrian pound and the Turkish lira—after the de facto authorities mandated using Turkish lira to overcome exchange rate differences; and the difficulty of marketing products.

The strain of plowing lands; lack of artesian wells for irrigation; shortage of pesticides and fertilizers; and the inability to sell the crops prompted Muhammad Alahmad (a 40 years old farmer) to rent his 10 acres in northern rural Idlib, on which Ard al Watá camp was built; hence he waived his production for three years.

The land that once cultivated wheat, barley, lentils, and chickpeas has turned into one of the private shelters, which account for about 70 percent of the total land. According to statistics by the United Nations shelter and camp organization, this land has nearly 1172 camps, housing more than 900 thousand displaced people in the region, out of a total of 1.5 million who live in camps.

Agricultural lands are considered a destination for the displaced who prefer the vast areas to reside in larger numbers with their families and relatives, despite their suffering from the absence of adequate infrastructures and social services such as sanitation system and paved roads, as 10 percent of the private lands used for the camps are considered uninhabitable. About 50 percent are in a suspended state. The residents may face deportation when their leases expire.

A previous article titled “Camp residents face another winter under dilapidated roofs,” Enab Baladi shed light on the suffering that camp residents go through due to the lack of infrastructure and the inappropriate sites. Enab Baladi also discusses options and solutions that people under the threat of being kicked out of the owners’ agricultural lands can adopt. The response by the Syrian Salvation Government (SSG) service department spoke about work in process to prepare appropriate land to which the camps will be transferred. However, no schedule for that was set.

For his part, Rammah explained that the farmers did not receive support from any responsible authorities, which always justify this by the lack of funding and the inability to secure what is needed.

Continuous demands and needs… Do farmers’ words fall on deaf ears?

After he was forced to flee bombardment and airstrikes on the village of Naqir in the southern countryside of Idlib, farmer Muhammad Ramah (49 years old) did not quit agriculture. Instead, he rented two plots of land—when he was displaced to Kardaryan in the northern countryside of Idlib a year and eight months ago—with an area of 175 dunums, at a cost ranging between 35 and 50 US dollar per acre for a year.

“The expenses are too high compared to the profit,” said Rammah to Enab Baladi, referring to the high expenses of the agriculture business of safflower, black seeds, and coriander, the products which he used to cultivate on his land. “We are now getting a quarter of what we used to make,” he said.

The problem is not limited to renting the land. Rammah has other expenses, such as the seeds and fertilizers’ high price and the workers’ wages. The wages, which are seen as too little for the employees and too much for the employers, are not supervised or monitored by any entities. “Workers work for pennies. They only need to put food on the table during the crisis with the uncontrolled rising of prices in the region,” he said.

Even for farmers working on the region’s most popular products, such as olives and pomegranates, this year’s season has been disappointing with a lack of market activity and high prices.

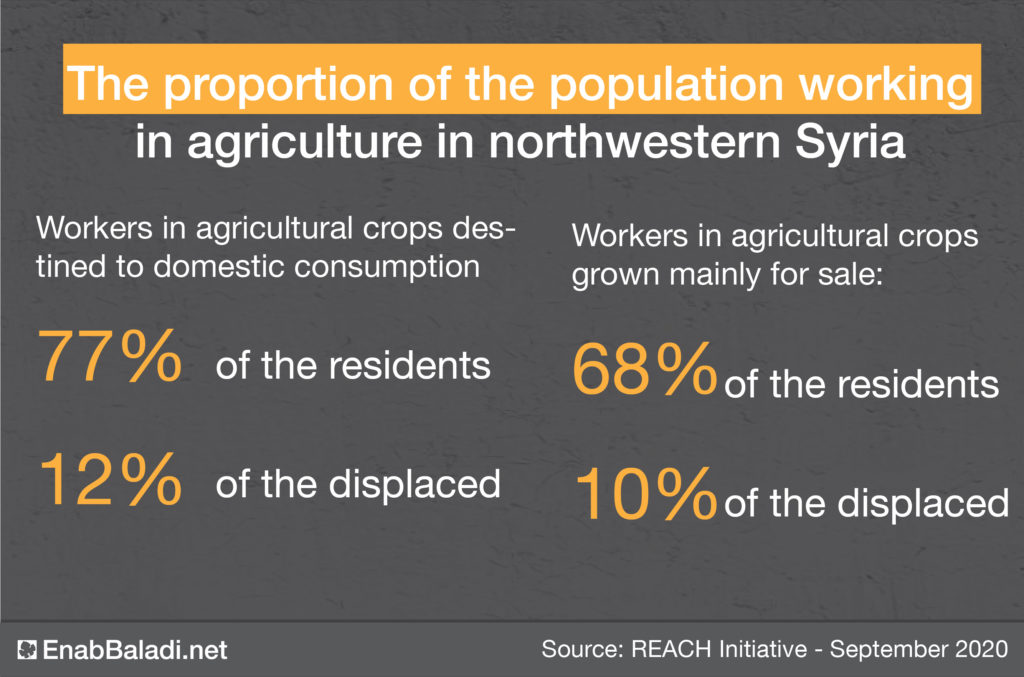

Cultivating food crops is a source of income for 77 percent of the residents in northwest Syria. In comparison, crops destined for sale are a source of income for 68 percent, according to the latest statistics of the REACH initiative on the humanitarian situation in the region during the last September. Around 12 percent of displaced people in northwestern Syria depend on growing crops mainly for domestic consumption, whereas 10 percent of the displaced cultivate agricultural crops destined to sell. Furthermore, workers in the agricultural sector feel neglected by the governing institutions.

The program “What’s Your Problem” conveyed the voice of chicken farmers in al-Bab city in northern Aleppo, who complained of the lack of support and services along with the increase in blackmail payments and restrictions on their work, in addition to the economic losses in the region.

Avaiblitity of job opportunities but not in agriculture

Fatima works in cleaning garlic up by removing the leaves at the neck and trimming the roots for ten hours a day. This easy work has become a strenuous task she has to endure for ten Turkish Liras per day.

That mother of five children could not find a better job where she stays (Atma camp near the Syrian-Turkish border). She used to work in sectors like cleaning pistachio and harvesting olives, cumin, coriander, chickpeas, and black seed to make a living.

According to Fatima al-Muhammad, work used to be “better” in the agricultural sector. She told Enab Baladi that the diversity of crops and the vast land created many job opportunities. These opportunities depend on seasons now, such as the harvesting season.

Fatima pointed out that the expenses that she had to pay were less when she was in her village and that the Syrian currency was more stable at that time. “Now, the wages are low compared to the effort and working hours. If I had found a better job, I would not have chosen this one,” she said.

Working from home encourages women to participate in agricultural work. Whole projects depend on them, such as preparing the winter supply or sieving plants and crops before selling or exporting them, but the low wages keep these women among the “most vulnerable” in the region, according to Relief classification.

Being supervised by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), the livelihood support focuses on simple food production, agricultural activity support, and livestock-based food production. That is by helping farmers to vaccinate their herds, providing aid to more than 11,000 farming families, as mentioned in its report issued on 20 November.

According to the latest OCHA report on the number of beneficiaries of livelihood support, more than 400,000 people received agricultural aid during the first four months of this year. Most of this aid was related to livestock vaccination, while agricultural inputs and infrastructure rehabilitation came in the second and third places, respectively.

The OCHA food sector estimates that the agricultural and food sector needs $ 1.1 billion in aid.

A harvester in the northern countryside of Aleppo harvesting barley – 30 May (Abdussalam Majaan / Enab Baladi)

Closing border crossings against COVID-19…

What is the state of import and export?

“Today, we are in a large prison as long as the crossings are closed. We can only trade with each other,” said merchant Abdulhamid Alzumar from al-Bab city. He talked to Enab Baladi about the impact of the spread of COVID-19 on the import and export of agricultural products in his “stricken” city.

The import of food products, most notably apples, oranges and potatoes, is restricted to the Turkish gate. This gate also closes and opens according to the waves of the virus spread and its prevention measures, according to al-Zumar.

Al-Zumar used to run was sufficient to provide job opportunities for 15 employees before the spread of the virus that began last July in the region. Unfortunately, closing the crossings as part of the preventative measures taken by the Syrian Interim government and the SSG reduced their numbers to a third, as explained by the tradesman.

The currency and the customs expenses are high and paid for twice when importing from Turkey, once in Adana, Turkey, and again at the Syrian crossing. These difficulties added to the problems that the tradesmen face. “When tradesmen face continuous loss, they stop their business’’ said al-Zumar, pointing out that closing the gate caused the destruction of goods coming from regime-controlled areas. The people in charge at the border gate refused to sterilize the goods or let them in.

“Export is the most profitable,” said merchant Adnan Al-Zumar. He also stated that pomegranate and onions are the main two products exported to Iraq via Turkey. As the agricultural products also used to be exported to the eastern region and the regime-controlled territories.

“If exporting is possible, farmers make a better profit and the value of their products will increase; otherwise, the yield will accumulate, and loss takes place when the prices drop,” said al-Zumar to Enab Baladi, adding that “a small portion” is what he exports, given the scarcity of crops available in the northern countryside of Aleppo.

Ahmed Abu Staif, a merchant in Idlib, explained to Enab Baladi that the value of any product increases when exporting by at least 20 percent, and while the export of food products is limited to the surplus, especially legumes and spices, their impact on domestic consumption is “relatively weak.”

According to Abu Staif, export has both negative and positive sides. The negative is the prices rise when the exported product decreases in the local market. This is limited to products that are not consumed in abundances, such as black seed and cumin. The positive side is manifested by market activity and profit.

Exportation of crops is relevant to the product variety. As the rate of spices exportation reaches 90 percent, and with the decrease in the percentage of exports from India in the current year, the price of a ton of black seeds in the Gulf markets reached three thousand US dollars while it had never exceeded 1,300 US dollars in previous years. On the other hand, 50 percent of the legumes are exported, of which Iraq is the main destination, unlike wheat and barley, which are completely consumed locally.

Abu Staif believes that the most in-demand products to be imported to Idlib are chemical and organic fertilizers. He said that COVID-19 had a big local and external impact on import and export as it weakened consumption.

Agriculture is an insufficient source of income for food security

In developing countries, agriculture is a major source of income for the state. Governments work on improving it with special and constant attention, but in Syria, war conditions have clearly affected the agricultural sector and farmers adversely.

The arable lands constitute approximately 32 percent of Syria’s area, of which 1.5 million hectares are irrigated lands, and 3.6 million are rain-fed lands (dependent on rainwater for irrigation).

With the beginning of the tenth year of the Syrian revolution, the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) said that Syria’s humanitarian needs became unusually high due to the displacement and destruction of agricultural infrastructure, which has affected the livelihoods and food security.

According to the “FAO” assessment, 9.3 million people suffer from acute food insecurity in Syria, and 1.9 million others are at the same risk. These numbers are expected to rise this year due to the lack of job opportunities and high food prices.

4.3 million people in northwest Syria suffer from food insecurity. Two-thirds of the population are displaced and depend on food aid for their livelihoods. While agriculture only meets 58 percent of the population’s needs for bread, according to the OCHA food sector assessment.

According to an estimation by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), 237,000 people in need do not have food aid available in their areas, while food aid is provided to more than 1.3 million people.

Food prices have increased in northwest Syria by 100 percent from March to September. Moreover, the food basket price reached 158.130 SP (74 US dollars) during the last six months, according to the “REACH” initiative’s assessment.

Governmental efforts to organize work… Are they sufficient?

The agricultural organization within the Interim Government in the northern countryside of Aleppo is carried out through coordination with local councils; the first step is to “agree” to prepare the necessary statistical records to organize agricultural work with the councils, as explained to Enab Baladi by Deputy Minister of Local Administration and Services for Agricultural Affairs, Nazih Kaddah.

Work is currently underway to grant agricultural licenses to farmers and breeders according to each’s real possessions based on real estate documents and sensory inspection made by the directorates of agriculture. However, obliging farmers to implement the agricultural plan is “not possible at this time,” according to Kaddah.

The government is working through agricultural institutions, such as “the General Organization for Seed Multiplication” to secure wheat and potato seeds, fertilizers, and pesticides of “excellent properties and reduced prices,” in addition to agricultural services at reduced prices, such as harvesting, cultivation, and pesticide spraying.

As for the SG-held areas in Idlib and the western countryside of Aleppo, Assistant Minister of Agriculture and Irrigation, Eng. Ahmad Alkawan told Enab Baladi that agricultural work is organized through several solutions and steps, which are as follows:

-Opening new agricultural divisions in the sub-districts as required to provide the necessary services to the agricultural sector (livestock and vegetation).

-Working on setting up a general plan for vaccinating livestock against the most common diseases.

-Working “as much as possible” to re-protect the forests against deforestation and overgrazing and making room for the forest to restore itself, especially the forests of Jisr al-shughour, after it had been exposed to more than 1,200 fires since the beginning of this year up until November, according to “Civil Defense” statistics.

-Supplying departments and people with agricultural engineers and veterinarians.

-Establishing a micronized irrigation system (sprinklers, valves, hydrants, etc.) to contribute to general control campaigns of strategic crops when necessary (such as combating short-horned grasshopper and sunn pests).

-Securing weather stations and deploying them appropriately, helping farmers anticipate frosts, etc.

-Preparing studies for the use of alternative energy.

-Encouraging farmers to grow strategic crops, such as cotton and beets.

Displaced women in Barisha camps collect mallow weeds from the wilds of the mountain to prepare them for food – 13 March 2020 (Enab Baladi)

– Developing rainwater harvesting projects, by pumping the largest amount of rain and torrential water to the “al-Balaa” reservoir in the countryside of Jisr Alshughour southwest of Idlib, from the main complex of the main banks in the Plain of Roj, west of Idlib. Then, increasing the storage ratio in the “Qastoun Dam”,” which is the only dam in the al-Ghab Plain, by diverting the torrents surrounding the dam to the inside.

-Equipping public and private wells and irrigation projects on the Orontes River with solar energy systems of appropriate capacities, to reduce fuel consumption to the minimum, and working on reducing the water consumption in irrigation with drip and sprinkler irrigation systems, rather than flow irrigation.

-Establishing “advanced” irrigation networks, via irrigation lines made of “polyethylene” with high specifications, high quality, and moderate economic cost.

Despite the stated plans, the statistical data show a lack of job opportunities and widespread unemployment appears, as a result of the lack of support and the ability to start agricultural and commercial projects. According to the assessment of the “REACH” initiative for the humanitarian situation in northwest Syria last September, 78 percent of the resident population in the region and 61 percent of the displaced are in need of a job.

The cause of unemployment was the need of 79 percent of the residents and 53 percent of the displaced for work-related equipment, and the need of 72 percent of the residents and 68 percent of the displaced for humanitarian projects that provide training and livelihood opportunities. 36 percent of the residents and displaced people stopped to work because they needed funding to start their projects.

if you think the article contain wrong information or you have additional details Send Correction

النسخة العربية من المقال

-

Follow us :

Most viewed

- Al-Hijri escalates against Damascus: A "radical" government

- Governor of As-Suwayda signs understanding agreement with al-Hijri: Key details unveiled

- Turkey confirms continuation of its operations in northeastern Syria

- Al-Sharaa signs draft constitutional declaration

- Al-Sharaa forms National Security Council in Syria

A man sitting on his vegetable cart in a marketplace in Idlib city - 7 April 2020 (Enab Baladi/Anas Alkhouli)

A man sitting on his vegetable cart in a marketplace in Idlib city - 7 April 2020 (Enab Baladi/Anas Alkhouli)

A

A

A

A

A

A

More In-Depth

More In-Depth