Ali Darwish – Ninar Khalifa – Nour al-Deen Ramadan – Khawla Hefzy

Long dialogue sessions initiated by the Syrian Kurdish parties, represented by two main poles, the Democratic Union Party (Partiya Yekîtiya Demokrat, PYD) and the Kurdish National Council, and independents, since November 2019, have defused the political deadlock between them.

The intra-Kurdish dialogue started with an initiative launched by the leader of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), Mazloum Abdi, following the Turkish-backed Syrian opposition’s offensive code-named “Operation Peace Spring” east of the Euphrates, in October 2019, and the US President Donald Trump’s announcement of his country’s withdrawal from some of its bases in Syria.

The two main poles of the dialogue sessions are the US-backed Democratic Union Party, which forms the core of the Autonomous Administration controlling northeastern Syria, and the Kurdish National Council, which has the blessings of Ankara and Iraqi Kurdistan and is part of the Syrian opposition bodies, whose offices had previously been closed, and a number of its members have been arrested. Its military arm was expelled from the area.

In a joint statement issued on 17 June, the two parties declared that the first phase of the dialogue conducted under the “Kurdish Unity” logo ended.

They highlighted that the (Dohuk 2014) agreement on “governance and partnership in administration, protection, and defense” is the basis for continuing the ongoing dialogue to reach a comprehensive deal in the near future.

These meetings were prompted by international parties, most notably France and the US, amid Turkish caution and anticipation from the opposition and the Syrian regime.

In this file, Enab Baladi analyzes the impact of the Kurdish-Kurdish dialogue, if an agreement is reached, on drawing the determinants of the future political process in Syria, the map of local and international alliances, the developments awaiting northeastern Syria, the role of the countries supporting the agreement, and the position of the people in the areas under the influence of the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (NES).

Positive or negative?

How does the agreement affect the political scene?

Amidst regional and international tensions, the US-Russian competition over political investment in northeastern Syria, Turkey’s attempts to play larger roles, the dialogues, which have been taking place since last May, and the announcement of an “agreement” on some provisions between the Kurdish parties, many questions were raised about the impact that the inter-Kurdish agreement, if successful, will have on the paths of political solutions that are still at a standstill, on the Kurdish homeland, and the possibility of arranging existing differences between them and setting other differences aside, to pave the way for consensuses that will reinforce the Kurdish situation and representation in all forums.

A “supreme Kurdish authority” with a “common political vision”

The general coordinator of the “Kurdish Reform Movement” and a member of the governing body of the “Kurdish National Council” Faisal Youssef, considered that the Kurdish-Kurdish consensus would contribute to the formation of a new situation in the Syrian political scene because it expresses the unified Kurdish position in various fields, through building a “supreme Kurdish authority” with the powers to represent the Kurdish people.

Youssef indicated, in an interview with Enab Baladi, that the Kurds constitute the second nationality in terms of population in Syria, and that they, by their nature, seek democracy, demand respect for human rights, and seek to reserve a place for them among the ranks of the opposition who believe in a political solution, and the implementation of international decisions on the Syrian issue.

“ Syrian Kurds is country’s largest ethnic minority and constitute about 10 percent of the country’s population , and they are mainly concentrated in three regions, which are Hasakah governorate in northeastern Syria, Ain al-Arab (Kobani) north of Aleppo, and Afrin northwest of Aleppo.”

Youssef pointed out that the emerging Kurdish authority, in which most Kurdish political forces will participate, will have a “common political vision” that includes a commitment to the current ongoing political process following international decisions on resolving the Syrian crisis, while stressing the need for expanding the circle of Kurdish representation in it, and the demand to guarantee the rights of all components of the Syrian people, including the Kurds, by reaching a federal system of government.

Furthermore, Youssef believes that the agreement between the Kurdish parties will reinforce the Kurdish nation’s role on many levels and end the disagreements that prevailed in the previous stage. It will also positively defend civilians and protect them from “terrorism” or any party that wants to harm them until a political solution to the Syrian crisis is found.

More space to share

The writer Shorsh Darwish agrees with Faisal Youssef, the General Coordinator of the “Kurdish Reform Movement,” that the Kurdish-Kurdish agreement will positively impact the political scene in Syria, in general, the Kurds in particular, politically and militarily.

The agreement will contribute to forming a “Syrian Kurdish” decision-making center away from regional tensions, and it will also give the Kurds of Syria the space to attend and participate in the political process as a unified bloc, and break the monopoly of the Kurdish parties that claim to represent the Kurds of Syria, according to Darwish.

Speaking to Enab Baladi, Darwish considered that the agreement would also contribute to progress towards a “Kurdish-Arab-Syriac” agreement in northeastern Syria, which would pave the way for all forces to participate in the political process, and grant northeastern Syria their appropriate representative share in the track of negotiation and constitution writing.

A new model will impose itself

The formation of a new administration in the region based on a Kurdish-Kurdish agreement and then a Kurdish-Arab deal may transform the new model emerging in northeastern Syria into a reality affecting the Syrian arena. The regime will not be able to ignore, according to Darwish.

He pointed out that this might prompt a negotiation process between Damascus and Qamishli backed by the US. However, he added, by saying, “Everything may remain on hold, subject to stopping the continuous Turkish objections to the Kurdish-led NES and convincing Russia of the feasibility of pushing the Syrian regime to negotiate with the administration.”

In the same vein, Darwish believes that the Kurdish-Kurdish consensus could play a role in easing Turkish pressure on the US, as Turkey seeks to end the presence of the Democratic Union Party (PYD) and to consider the region under the control of its Syrian Kurdish rival.

The involvement of Kurdish political forces, such as the Kurdish National Council, would give Washington a better position to respond to the ongoing Turkish allegations and threats.

Regarding the Kurdish body structure that will result from the agreement, Darwish expected that the administrative and military structure would be subject to changes. Still, it would not be radically different from the current model, indicating that the focus would be on the economy and political decision issues.

The initial agreement reached by the Kurdish parties last June concluded with the formation of a “Kurdish political reference,” provided that the quotas of the Democratic Society Movement (represented by the Democratic Union Party) would be 40 percent. The Kurdish National Council would be 40 percent and 20 percent for parties and forces not involved in the two political bodies.

Subsequently, the parties agreed that the number of members of the Supreme Authority would be 30, represented as follows: 12 from the “Democratic Society Movement,” 12 from the National Council, and eight political forces from outside the two bodies mentioned above.

According to the agreement, this authority is to draw up general strategies, embody the unified position, form an effective partnership in the NES bodies, move towards political and administrative unity, and participate in all other components.

It was also agreed to establish a joint committee to integrate the military forces and reject more than one military power in the Kurdish regions.

Mazloum Abdi, the SDF leader, said in an interview with al-Arabiya.Net, last February, that “all the attempts to solve the Syrian crisis and the negotiations that have taken place over the past years in the absence of representatives of the NES, have not achieved any results that could meet the needs of the Syrians.”

Abdi stressed the importance of the participation of the Kurds and all the Syrian components in the negotiations for reaching a political solution.

He considered that “the Constitutional Committee contradicts the UN Resolution (2254), as it does not represent all Syrians and this is a mistake,” indicating that “All the Syrian components without exception, should be involved so that we may say (a Syrian solution, a Syrian constitution, and Syrian negotiations).”

He added that the NES has become a real project that cannot be eliminated, and without looking at this project realistically, the solution cannot be achieved in Syria.”

What about the remaining components?

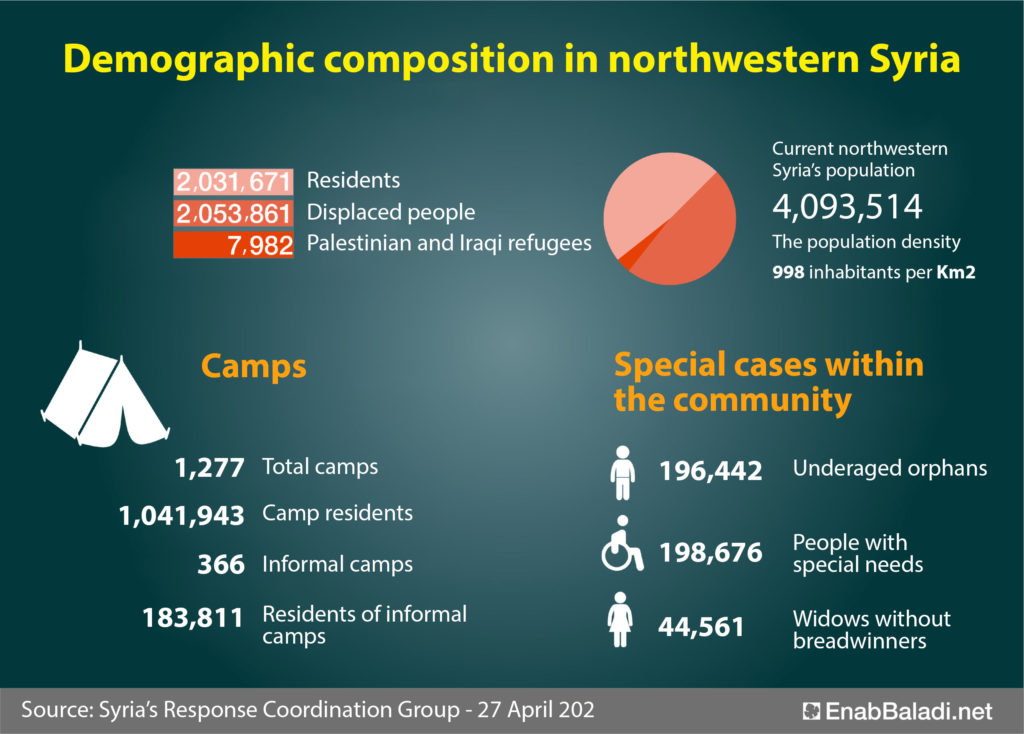

The Kurds in the NES-controlled areas do not constitute the largest ethnic group. The area is characterized by a diverse population, dominated by the Kurdish and Arab elements, and other ethnic groups, such as Syriacs, Assyrians, Armenians, and Turkmen.

Mudar Hammad al-Asaad, head of the “Political Board for al-Hasakah governorate” and spokesman for the “Supreme Council of Syrian Tribes and Clans,” pointed out that the “Political Board for al-Hasakah governorate” and “Supreme Council of Syrian Tribes and Clans” support any Syrian-Syrian understanding that contributes to achieving the interests of the Syrian people, their territorial integrity and implementation of relevant international decisions.

However, the Kurdish-Kurdish agreement comes within the context of sharing the region’s gains and removing the Arab component, which constitutes about 80%, from the political scene, according to Al-Assad.

Al-Asaad added: “This agreement undermines the unity of the Syrian territories. Also, the presence of the Democratic Union Party (PYD) in any gathering means the presence of a terrorist party, and that contributes to demographic change,” which is unacceptable.” He considers that “the solution that must be applied in Syria, in the regions of al-Jazira and the Euphrates is the expulsion of all outsiders,” implying “the Syrian regime, the Iranian and Russian militias, the Islamic State and the PYD.”

According to al-Asaad, finding a solution in the eastern zone should involve establishing a dialogue with the inhabitants of the governorates of al-Hasakah, Raqqa, and Deir Ez-Zor, to find an appropriate solution, irrespective of any foreign agendas, stressing the need to ensure consensus between all the inhabitants of the region.

Political analyst Firas Allawi, a native of Deir Ez-Zor governorate, considers that, if the agreement is concluded between the two parties, it will provoke a split between the Syrian opposition parties due to the involvement of the “SDF,” which has a conflict with the traditional opposition bodies implicated in the political process.

This split could even lead to the withdrawal of the “Kurdish National Council” from the “Syrian National Coalition” in exchange for the possibility of entering a political bloc supported by the “Moscow Platform” or a new bloc to the “Kurdish National Council.”

A dialogue preceded by unsuccessful attempts to reach an agreement

The initial discussions of the Kurdish-Kurdish dialogue, since November 2019, included removing legal obstacles to the “Kurdish National Council,” which is in agreement with Ankara, in the areas controlled by the “SDF,” to open its organizational and party offices, and carry out its political, media and social activities, without the need for obtaining any prior security approvals. Besides, the discussions were to remove all obstacles to the process of rebuilding confidence between all political and administrative actors in the areas of influence of the “Autonomous Administration.”

On 29 May, Mazloum Abdi announced the beginning of the second phase of the “Kurdish-Kurdish” dialogue, which was then going at a slow pace. Then, this dialogue reached a “preliminary agreement,» as confirmed by the Kurdish National Council member, Fuad Aliko, to Enab Baladi. He also pointed out that the visit of U.S. Special Representative for Syria, James Jeffrey, to northeastern Syria on 20 September, came after an agreement had been reached between the Kurdish National Council and the Democratic Union Party on the “Kurdish Political Authority,” which would be the supreme Kurdish political authority in Syria, after the second round of talks.

With every political change, there are previous failed attempts.

The “Kurdish National Council” refused to negotiate with the “Democratic Union” Party that previously formed the “Autonomous Administration,” closed the “National Council” offices, and arrested its members, without the presence of an international sponsor for the dialogue, according to a member of the “National Council” in a research seminar conducted by the Omran for Strategic Studies,” Center last July.

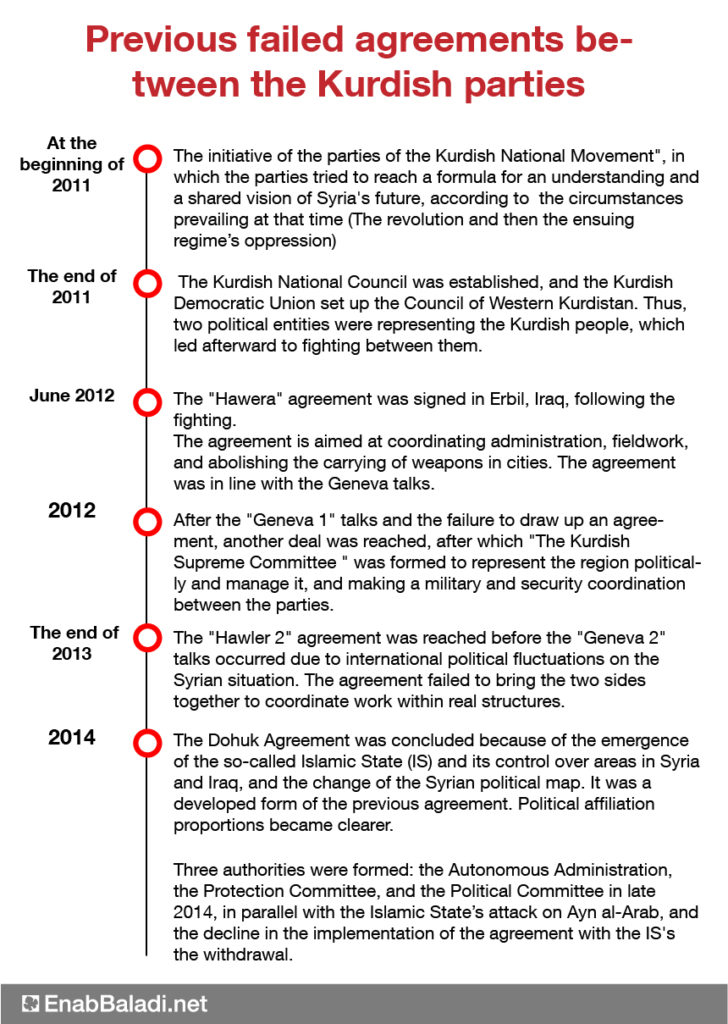

The “Democratic Union” and the “National Council” have been trying to start negotiations on power-sharing since 2012. They have concluded several earlier agreements, namely “Hawler 1”, “Hawler 2,” and “Duhok.” However, all these agreements failed.

The failure is attributed to several reasons related to the politics of the national and regional axes, on the one hand, and personal reasons related to the nature of the Kurdish parties itself on the other hand.

Badr Mulla Rashid, a researcher at the Omran Studies Centre and a specialist in Kurdish affairs, summed up in a research seminar the earlier attempts for dialogue between Kurdish parties since 2011:

-The first initiative was the creation of the “parties of the Kurdish national movement” at the beginning of 2011, during which the parties tried to reach among themselves a formula for understanding and a common vision about the future of Syria, in accordance with the prevailing circumstances at that time (the revolution and then the ensuing oppression of the regime).

-The end of 2011: The Kurdish National Council was established, and the Kurdish Democratic Union has formed a Council of Western Kurdistan, leading thereby to the emergence of two political entities representing the Kurds and the ensuing rivalry between such two parties.

The infighting led to the necessity of establishing an agreement between the two parties, which resulted in the “Hawler 1” agreement, in June 2012, in Erbil, Iraq.

The agreement included coordination between the city administration and fieldwork and the abolition of carrying weapons in cities, and it was in line with the “Geneva 1” talks.

After the “Geneva 1” talks and the failure to draw up an agreement, another deal was reached, after which “The Kurdish Supreme Committee ” was formed to ensure political representation and administration of the region as well as military and security coordination between the parties.

As a result of the international political fluctuations on the Syrian situation, and before the “Geneva 2” talks had been held, the “Hawler 2” agreement was concluded at the end of 2013, but it could not attract the two parties to coordinate work within viable entities.

After that, the Democratic Union Party proceeded to announce the formation of the Autonomous Administration in Northern and Eastern Syria, on January 21, 2013, the day before the start of Geneva 2.

With the emergence of the “Islamic State” in mid-2014 and its control over areas in Syria and Iraq, the change of the political map in Syria, and the attacks led by the Islamic State on Ayn Al-Arab (Koubani), a new agreement was imposed, represented in the “Dohuk” agreement, which was a development of the previous form. Political ratios appeared in a way Larger. Political affiliation proportions became much clearer than before.

Three authorities were formed: the Autonomous Administration, the Protection Committee, and the Political Committee in late 2014, in parallel with the Islamic State’s attack on Ayn al-Arab, and the decline in the implementation of the agreement with the withdrawal of this Organization.

With Turkey’s Operation Peace Spring on 9 October 2019, Abdi called for a dialogue between the Kurdish parties, in an attempt, with American support, to curb the Kurdish loss as far as the governance of Syria is concerned. Soon afterward, the dialogue turned into direct negotiations between the two sides.

How the dialogue affects Turkey

So far, Ankara has not shown any satisfaction with any Kurdish-Kurdish dialogue and continues to adhere to its traditional position of rejecting any Kurdish entity on its borders.

And if this entity is ever created in the future, political analyst Hassan al-Nifi has excluded any recognition of it by Ankara, expressing the likelihood that this entity’s upper limit would be an “autonomous administration” “administrative decentralization” at best.

Turkey continues to express its concerns in the media about the results of the dialogue and the agreement that may be reached, according to the statement issued by Abdullah Kado, the member of the political committee of the (SNC) representing the “Kurdish National Council,” in an interview with Enab Baladi.

However, the American sponsorship of the dialogue reassures Turkey to a certain degree. Ankara may be one of the most winning parties if the agreement sought by the “Kurdish National Council” succeeds since the latter is a member of the “coalition” allied to Turkey.

It will achieve the strengthening of the Kurdish opposition in particular, and the Syrian one in general, in exchange for weakening the regime, especially as Ankara supports the opposition to get rid of such regime that is In addition to the consolidation of more stability on its southern borders, according to a member of the “Coalition” and the “Council” Abdullah Kado.

Kado also thought it likely that U.S. officials will continue to communicate with Turkey in order to facilitate the process of dialogue to reach an agreement between the two parties (Ankara and the Democratic Union Party are among the most important allies of the Americans in the region).

He rejected the existence of a Turkish intention to pre-empt the agreement’s results to be concluded between the two Kurdish parties.

Moreover, there is no Kurdish project outside the concept of preserving the unity of the Syrian nation and land, neither theoretically nor practically, nor beyond the consensus with the Syrian national opposition representing the entire Syrian people, according to Kado’s expression. This was confirmed by the UN envoy to Syria, James Jeffrey, who said that Washington does not support any initiative that undermines any country’s interests or security in the region. He also said that the agreement’s support is part of the national opposition’s support to get rid of “terrorist” organizations and the Iranian presence.

Turkey had launched two military operations against the “Syrian Democratic Forces” to remove their danger from Turkey’s border with Syria, the first on the Afrin region in January 2018. It ended with the control of the Syrian opposition, supported by the Turkish army, over the area.

The second military operation was launched on the East of the Euphrates, in October 2019, and ended with controlling the two regions of Ras al-Ayn northwest of al-Hasakah and Tell Abyad, north of Raqqa, which are located on the Syrian-Turkish border.

Turkey categorizes the “Syrian Democratic Forces” (SDF), whose backbone is the “People’s Protection Units” (Kurdish), on the list of “terrorist” entities.

Ankara considers the “units” of the “Democratic Union” party an extension of the “Kurdistan Workers’ Party” (PKK), which is classified on the lists of “terrorism” globally and is accused of carrying out bombings and assassinations in Turkey and the world.

Franco-American gains?

Both the US and France are exerting efforts to achieve consensus between the various Kurdish parties in Syria, to bring points of view closer, and to end the state of estrangement which has prevailed between the opposing parties, especially between the Democratic Union Party (PYD) and the parties of the Kurdish National Council since the Democratic Union Party closed the headquarters of the National Council parties in its areas of control.

Like all countries that have interfered in one way or another in Syrian affairs, both countries have goals behind their focus on the Kurdish-Kurdish agreement’s success, and there are benefits that they seek to achieve.

France and America, along with the 76 countries of the international coalition, have taken care of the Euphrates’ eastern region since the international coalition’s announcement to fight the Islamic State (IS). This is motivated by the strategic importance and political influence of the region and natural resources and wealth, such as oil and gas, and other resources. The region is considered as Syria’s food basket, according to the statement of Abdullah Kado, a member of the political committee of the “SNC” for the “Kurdish National Council.»

According to political analyst Hassan al-Nifi, it is clear that the priorities in the American strategy over the Syrian geography consist of resisting Iranian influence in Syria. This is what has prompted Washington to stick to the “SDF” as an allied force through which Iran’s annexations in the eastern region can be resisted. For “SDF” to become “A force acceptable to all the region’s residents, it must be in harmony with the Kurdish forces or others.

France is pushing towards resisting Turkish influence and siding with the Democratic Union Party to delude French society. It supports all Kurds in the region, according to analyst Hassan al-Nifi.

“Syrian National Coalition” (SNC) and ” Syrian National Council” (SNC) member, Abdullah Kado believes that the intra-Kurdish dialogue would strengthen the Syrian opposition in the region and unify it because of the importance of the Kurds in the Syrian equation, as this dialogue paves the way for the transition to conducting a dialogue between the Kurds and their Arab and Assyrian partners, and others, thereby giving the Syrian regime and its allies, especially Iran and Russia a hard time.

The Democratic Union Party (DYP, and beyond it, the “SDF”’s cutting ties with the regime closes the door to any Iranian influence in the region. This may constitute pressure likely to spur the regime and its supporters to accept sitting around the international “Geneva 1” negotiation table on resolving the Syrian crisis and to consent, in practice, to Resolution 2254 and others, according to Kado.

The French and American efforts grew stronger last May. A round of negotiations was held between the Kurdish parties when the French delegation met for the first time with the Kurdistan National Alliance (KA), which is close to the Democratic Union Party.

Some representatives of France in the International Coalition had previously met with leaders from the opposition “Kurdish National Council» and expressed their support and backing for the efforts aimed at achieving rapprochement and understanding between the Kurdish parties.

The French efforts came in conjunction with other American ones, as illustrated by the visit of the representative of the US Foreign Affairs Department, Ambassador William Roebuck, and his assistant, Emily Brandt, at the end of last April, to North-Eastern Syria, and their meeting with a wide range of leaders of Kurdish political parties, to listen to their various opinions and suggestions on unifying Kurdish political forces.

France had previously launched an initiative, in 2019, to unify the Kurdish ranks and bring the “Kurdish National Council” and “Democratic Union Party” closer, but it failed to bring about a solution.

The French ambassador in charge of the Syrian file at the time, Francois Sénémaud, held meetings with representatives of the Syrian Kurds in the French capital, Paris, during April 2019, intending to bring together views and resolve the outstanding differences between the two sides.

The initiative then stipulated three main points: the commitment of all Kurdish parties to international decisions relevant to the resolution of the Syrian crisis, the strengthening of confidence-building measures between the conflicting parties, and participation in the political process.

Will the Peshmerga return to Syria?

Peshmerga, or officially “Kurdish Peshmerga forces,” is the term that the Kurds use to refer to their fighters, literally translating to “those who face death.”

In Syria, the “Syrian Peshmerga” or “Rojava Peshmerga” (Western Kurdistan) emerged in late 2012, when Kurdish officers who defected from the Syrian regime forces gathered after they had arrived in the Kurdistan region of Iraq and had been joined by civilian volunteers. The number of these forces is estimated at best at 12,000 fighters.

Since its creation, the Syrian “Peshmerga” has been a military arm of the “Syrian Kurdistan Democratic Party,” the core element of the Kurdish National Council, which is a part of the “Syrian National Coalition for Revolutionary and Opposition forces” before becoming the military wing of the Kurdish National Council in 2015.

The Peshmerga’s name came back to the surface with talks about its return to Syria in an advanced stage of the intra-Kurdish dialogue, according to a member of the “Kurdish National Council” Fuad Aliko, who made it clear that agreeing on the “Kurdish Political Authority” does not mean reaching a “comprehensive agreement” between the “Kurdish Council” and the “Democratic Union Party,” in the midst of points that were not discussed, including the return of “Peshmerga” forces from northern Iraq (Iraqi Kurdistan).

The Kurdish “peshmerga” fighters participated in the battles of the city of Ayn al-Arab (Kobani), in October 2014, against the “Islamic State” group, under the command of a joint operations room, which was run in coordination with the Erbil operations room of the US-led international coalition.

The “Peshmerga” forces crossed through Turkish territory to station their vehicles and fighters in Ayn al-Arab, coming from the Kurdistan region of Iraq.

if you think the article contain wrong information or you have additional details Send Correction

النسخة العربية من المقال

-

Follow us :

Most viewed

- Kurdish Protection Units: Key point of contention between Damascus and SDF

- Arrests and explosive seizures in security campaign in old Damascus

- Syria and Lebanon sign agreement for cooperation in border demarcation

- Struggle for Syrian phosphate awaits fate of Russian contract

- Koya: A border village paying the price for rejecting Israeli presence

Kurdish fighters waving flags in Tell Abyad - 2015 (Reuters)

Kurdish fighters waving flags in Tell Abyad - 2015 (Reuters)

A

A

A

A

A

A

More In-Depth

More In-Depth