Enab Baladi’s Investigation Team

The Syrian society has so characteristically become a mixture of civilians and militants , and a state of permanent alert has been reflected among many citizens who resorted to purchasing light and medium weapons and keeping them at their homes under security and political pretexts that they use to justify the need to defend themselves amid the security chaos which the country has been witnessing for years.

However, this phenomenon has resulted in controversy as the aim behind acquiring weapons has exceeded “the need to protect oneself” to turn into a show-off tool in civilian areas during weddings, public celebrations and funerals of the dead victims. These weapons have become easily accessible to people who do not know how to handle them, leaving behind their parades victims and tragedies which added nothing but more misery to the one that Syrians are already experiencing.

Some Mortal Ceremonies

As tradition has it in Syria during happy occasions, and as an expression of joy shots are unconditionally fired in an attempt to make an ordinary event extraordinary, and this is done in honour of the host and at his expense as well.

Perhaps these customs are linked to a military history in the Middle East to which revolutions and wars are not alien and are encouraged by social customs based on “publicizing” social events.

However, neither “modern civilizations” could check and refine this legacy, which had turned many happy occasions into funerals, nor did “Civil laws” succeed in changing the people’s “military” ways of expression.

Nowadays, this way of expression in Syria is no longer confined to happy occasions but is used in military events that occur on the ground during the war and is also present whenever there is “a victory” to be celebrated or a dead person to be taken to the cemetery.

The uncontrolled proliferation of weapons and their accessibility further enhance the chances of using them there where they should not be used, thereby increasing the number of victims and casualties of such misuse.

One of the injuries in a shooting incident during a wedding in the city of al-Bab – August 2017 (Facebook)

Under the bullets of “Shabiha”

In regime-held areas, there are numerous reasons for celebration according to its loyalists, the National Defense Forces and other allied militias, and they are often accompanied with many cases of indiscriminate killing of civilians.

Some of these cases of weapon misuse s are related to political and military events, funerals of combat victims, treatment of wounded persons, and conflicts among loyal militia members.

In the city of Lattakia, where it is common to find armed civilians, an indiscriminate shooting committed by a member of the Desert Hawks Brigade took the lives of five family members in April, causing great public rage, which was then put down through the province’s officials’ promises to “hold criminals accountable”.

The killing of a 16-year-old boy in July after “a poker game” rocked Damascus after it turned out that the perpetrator was the son of an official and had been smuggled out of the country, and the case ended up in court archives with none held accountable.

In the city of Salamiyah, in the countryside of Hama, an 18-year-old girl was killed by a gunshot during celebrations of the score of the Syrian team and Australia’s match in October.

During last year’s New Year celebrations, three people were killed and about 50 others were injured in all over Syria following random shootings in celebration of the New Year.

Recently, loyalist pages mourned Ahmed Talal Fares, a student at the University of Mechanical Engineering and an inventor, who was shot by a “stray bullet” near the Abbasids Square in Damascus.

Fighters and civilians “playing” with weapons

Arms trade is active in the areas held by opposition factions, thus making it pretty much easier for fighters and civilians to get hold of weapons without the need to obtain permits or the presence of competent surveillance authorities. Added to this is the state of insecurity that forces civilians to acquire arms for “self-defense.”

The heavy proliferation of weapons has often had a negative impact on civilians, especially in cases of internal fighting among military groups, in funerals, and in weddings and social events.

The civil defense official in the city of Idlib, Yahya Arja, assured Enab Baladi that the number of victims of the random use of weapons range between 5 and 10 wounded and dead per month.

In the area of the “Euphrates Shield” operations in northern Aleppo, the indiscriminate use of weapons in popular occasions caused 34 injuries between weddings and other celebrations, according to Major General Abdul Razzaq Aslan, commander-in-chief of the National Police and Public Security Forces.

Aslan confirmed to Enab Baladi that northern Aleppo countryside witnessed dozens of injuries resulting from shooting related to personal disputes during which the weapon was used, thus civilians who had nothing to do with the incident were injured.

In southern Daraa, Enab Baladi’s correspondent identified several cases of victims of indiscriminate use of weapons, some of them were victims of factional conflicts, and others of either funerals or celebrations.

Last week, a girl was killed in the city of al-Sanamayn following clashes between fighters. A similar incident resulted in the killing of a man in the town of Kafr Shams.

The number of victims of celebrations is clearly growing, especially in the refugee camp area near the town of Da’el, where indiscriminate bullets can easily penetrate tents fabric and kill innocent victims.

“Militarization of society”…

Challenges that threaten the present and the future of the Syrians

The problem of the victims of stray bullets within Syrian regime and its opponents’ areas has been raised amid warnings that have not been restricted by regulating laws, because of the difficulty of controlling the sources of these weapons, which were accessible to the citizens who were “seeking safety” and who have consequently become a source of fear and insecurity for other citizens.

Accurate official figures about the number of victims who were killed or injured because of the indiscriminate bullets in civilian areas are absent, except for some figures issued by some local authorities that witnessed people killed and injured in bullet shooting incidents that occurred both during funerals and happy occasions.

Enab Baladi contacted these authorities within the Syrian opposition held areas to identify the causes and manifestations of the proliferation of weapons among civilians and the role of the war in promoting this phenomenon.

Instinctive motives

According to Enab Baladi’s correspondent in Daraa, the phenomenon of arms possession among civilians in Daraa is unusually widespread. He pointed at civilian tendency towards buying weapons under the pretext of “self-defense” at a time dominated by insecurity.

Commenting on this phenomenon, Ismat al-Absi, head of the Dar al-Adel court in Daraa, attributed the reasons for the proliferation of weapons among civilians to several matters which he summed up as “inherent instincts of every human being at times of war and crisis, in order to protect oneself, especially with the absence of the police and road security.”

In an interview with Enab Baladi al-Absi added that the availability of weapons in Daraa, the absence of necessary procedures and the failure to apply the legal conditions for possession of weapons, helped them spread in every house.

However, the head of the court stated that injuries caused by random bullets in ceremonies and events are “relatively limited” and often occur during individual fights among young men who are not good at using weapons or upon joking with each other when dismantling and assembling weapons.

Security vacuum

The situation is not that different in the northern countryside of Aleppo. The civilian possession of arms has become a “normal phenomenon” in the early years of the war in Syria.

In this regard, Major General Abdul Razzaq Aslan, commander-in-chief of the National Police and Public Security Forces in the northern countryside of Aleppo, says that the phenomenon has started before the formation of the judiciary and the police in the liberated areas in northern Syria. It was easy for anyone who has money to own weapons. However, after the formation of judicial and security committees, there has been a tendency towards limiting the weapons to two bodies, the National Police and Public Security Forces and Free Syrian Army. He pointed out to the ongoing and gradual efforts to control the matter.

Abdul Razzaq Aslan, commander-in-chief of the National Police and Public Security Forces in the northern countryside of Aleppo.

In an interview with Enab Baladi, Aslan attributed the reason for the militarization of Syrian community in the countryside of northern Aleppo to the opening the doors in front of owning weapons, under pretexts of fighting the regime and legitimate self-defense. However, with the instability which the region has been witnessing and the multiplicity of the intervening parties, chaos and the culture of possession of weapons have been spread, robbery and kidnapping crimes have increased, and gangs that took advantage of the lack of security to exercise their activities have multiplied.

He continued “To be realistic, we cannot deny that at some point, civilians had no other solution to protect themselves, but now the situation is quite different. The indiscriminate deployment of weapons by civilians has become a problem, especially in areas where the national police forces and other institutions that are capable of playing the role of state institutions do exist.”

At the same time, Major General Aslan pointed out that the Syrian society has started to accept the idea of abandoning weapons, especially after there have been cases of misuse in weddings and local popular events, in which their use often leads to civilian casualties.

A show of strength

In the city of Idlib, Civil Defense official Yahya Arja says that weapons are spread among civilians in the city, because they think they can give them a sense of security.

Arja, who examined many cases in which civilians have been wittingly and unwittingly shot, added to Enab Baladi that “The problem lies in the availability of weapons to minors, who show their strength through them and get involved in fights that often end up with the injury or death of one of them.”

In the western countryside of Aleppo, the experience of arming civilians differs from the aforementioned areas. The director of Aleppo Free Police, Adeeb Chlaf, says that weapons are only spread in houses with one of their inhabitants belonging to a military faction. “However, weapons are less likely to be found among civilians who are far from the military, for even if weapons exist, they are hidden and are not openly shown in the streets.”

Chlaf added to Enab Baladi that weapons are often misused in weddings or during funerals. He pointed out that weapons are scarcely used in fights or in the hands of gangs. He also considered that the spread of weapons among civilians is “normal” as there are close fronts to their areas of residence and work.

Possession of weapons in Syrian law. What about licensing?

| Legislative Decree No. 51 of 2001 of the Syrian Weapons Acquisition Law provides 55 items that regulated the matter of weapons and ammunition in the Syrian society in all their aspects.

Article (5) of the aforementioned decree states that “it is prohibited to carry or own pistols, hunting rifles and ammunition without prior authorization”, while Article 10 states that “the maximum number of weapons allowed per person is one pistol and one hunting rifle.” Article 11 of the Legislative Decree prohibits the use of weapons in residential areas and during gatherings such as celebrations and camps, and in industrial and oil zones. Article 18 stipulates that the person who applies for any licensee has to be 25 years old, to be uncharged and residing in Syrian territories, as well as “physically eligible”. |

In 2011, the decree on the possession of weapons in Syrian law appeared to be “unenforceable” in areas under and out of the control of the Syrian regime, especially with the deployment of armed militias in both regions as the peaceful movement turned into an armed one.

Several monitoring gaps and suspicious facilitations have helped in the militarization of the Syrian civil society and made light and heavy weapons easily available in shops that are spread in public markets.

However, the largest gap in this area has been the possibility for civilians to possess weapons without obtaining a legal license from the specialized authorities in their areas, while some of the governing authorities inside Syria have legislated other laws through which they made weapon possession among civilians even easier and provided them with legal authorization under conditions.

In the opposition-controlled areas, the procedures that regulate the possession of weapons are almost absent, according to Enab Baladi’s correspondents in Daraa, Idlib and Aleppo. The self-governance areas in northern Syria have regulated the acquisition of weapons through the enactment of laws through which they grant licenses to those who wish to purchase them. However, these laws were considered as “a double-edged sword”, as they facilitated the conditions for granting weapons licenses.

In April 2016, the Legislative Council of the self-governance in Hasakah approved the weapons licensing law at the 10th session of the Council after amendments to the draft law which was submitted to the Council.

The approved law included an amendment to the allowed age of carrying weapons from 21 years old to 18 years old, “in view of the presence of members of Asayish and the People’s Protection Units who are at the age of 18, and who might need to carry weapons.”

The law contains 15 articles dealing with various matters related to possession of weapons, from the eligibility requirements to the fees, types, and the quantity of weapons that are allowed to be licensed per person.

Some of these conditions state that the person who wants to own a weapon must not be less than 18 years of age, to be a resident of areas under the control of the self-government, and to obtain a residence permit from the Kumin (the smallest administrative unit in the neighborhood) and certified by the People’s House (the administrative circle in the region), affiliated to the self-government.

Lawyer Radwan Seydou said that according to Syrian law and the law of self-governance, no one is allowed to carry weapons unless they are licensed. He pointed out that anyone who possesses an unlicensed weapon would face several penalties, the first of which is the confiscation of the weapon and a financial fine, as well as 6-month to one-year imprisonment sentences.

However, in 2011, things have changed in relation to weapons’ possession according to Seydou who told Enab Baladi that serious problems have arisen as a result of recklessness in granting permits to civilians and allowing them to carry weapons.

He continued “All the society members have become owners of some type of licensed or unlicensed weapons, which they carry with them wherever they go, and use at any dispute or fight. This has resulted in the death of many innocent people.”

Radwan Seydou, a lawyer from Qamishli, demanded that this phenomenon, which “threatens the security and stability of the society in the future,” be addressed, and that no weapon licenses be granted to civilians under any conditions.

How did weapons spread in Syria?

Syria has become a conflict zone of international interests, in which various Russian, US, Iranian and Turkish weapons are laid down. They are used by the Syrian regime and the militias that fight alongside it and are used by various opposition factions, including the Kurdish forces.

The year 2013 is the pivotal historical turning point in relation to the spread of weapons among civilians in Syria. Before 2013, weapon dealings were limited to the activity of weapons-trafficking networks in conjunction with the protests and the civilians’ desire to protect themselves from the security forces of the Syrian regime.

The unstable security situation in the early years of the Syrian revolution has facilitated the emergence of these networks, especially in the border areas, from Iraq and Turkey to the East and North, in Jordan to the South, and to Lebanon from the West. This led to the spread of the public selling and buying of weapons for prices that have facilitated their circulation, amid the Syrian regime’s negligence, which analysts said it was “deliberate”, and that it was aimed at turning the popular movement into an armed action.

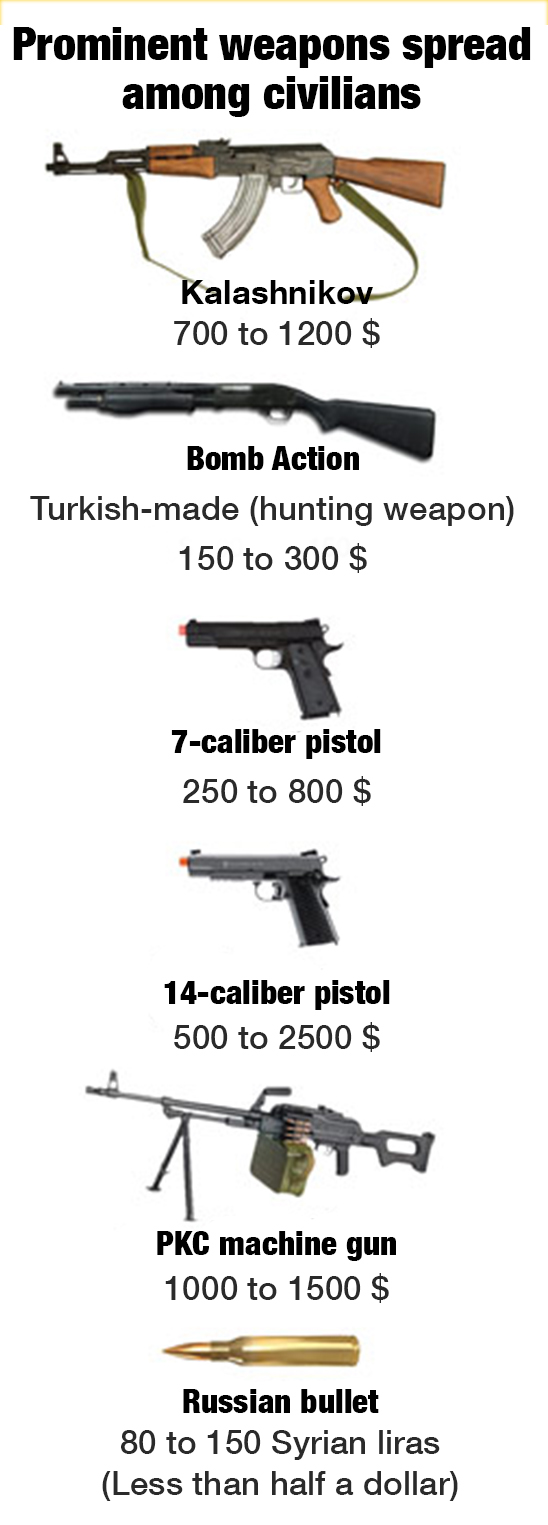

There are different types that are sold for prices that start from 20 thousand Syrian pounds, as well as countless types of ammunition, whether the light ones as Kalashnikov or heavy ones as RPG missiles. The weapons trade has become a “culture” which civilians brag about, which reached the level of labeling the weapons that are being promoted for sale with names such as Umm Al-Awasef (Mother of the storms), the Iraqi babe, Abu Da’n (The chinned), NATO, the Pakistani.”

The munitions and weapons which entered into Syria varied. The opposition factions regions were a main route to the interior, especially the central regions, which relied on their weapons from the northern and eastern regions through traders who bought them from within Turkish and Iraqi territory. It also played a role in the deployment process in the south of Syria areas, as Daraa and Quneitra, through intermediaries of Jordanian territory.

The responsibility for the proliferation of weapons cannot be limited to the opposition, since the regime had a prominent role through its National Defense militias, which assumed and took responsibility for the arms trade, in addition to the soldiers of the Syrian Army who, by early 2014, turned into market traders as well. They were the main source of weapons in the city of Damascus and its countryside and the main cities of the Syrian regime in Lattakia and Tartus.

After the year 2015, the arms market moved from shops north of border villages to social networking sites. Enab Baladi saw pictures of various weapons, each with its price in dollars, and a large number of activists interacted with the pictures either through providing price estimates or being sarcastic.

Idlib has become a black market for arms sales, and merchants have devoted pages on social networking sites (Facebook and Telegram) to display their goods. What made matters even worse was the large numbers of fighters it has received in recent years, who have sold most of their weapons on the black market and privately to civilians.,

Parties “struggling” to control the use of weapons

Since 2012, Syria has been a battlefield of 185 square kilometers. In addition, “safe” areas seem almost non-existent, which made the spread of weapons among civilians too difficult to control, in the presence of hundreds of factions and militias fighting on the ground and carrying out the tasks of bringing their weapons into their areas of control.

However, security, police, judicial and civilian authorities in the opposition controlled areas have made vigorous moves to control the random use of weapons, either through local decisions to which civilians and combatants are subjected, or through judicial movements or awareness campaigns.

In the regime-controlled areas, the attempts seemed to be few and limited to “calming the citizens” through decisions to revoke some security cards from the National Defense officers, thus depriving them of possession and uncontrolled use of arms, or simply raising arms licensing entitlements.

Local “penal laws”

Major-General Abdul Razzaq Aslan, Commander-in-Chief of the National Police and Public Security Forces, pointed out that “work is currently underway to license arms according to legal standards, in addition to controlling any attempt to sell arms randomly, according to a well thought out plan whose results show the difference between the previous and current situation”.

“As police and national security forces, we hold agreements with the Free Army by identifying and licensing the type of weapon that individuals can legally obtain and keep. Therefore, any unlawful, unauthorized and not licensed weapon will be confiscated,” said Major-General Aslan in an interview with Enab Baladi.

The Free Police tasks are not free of some difficulties in this context, as Major General Aslan insists that police forces sometimes have to engage in fights with some people who misuse weapons, before they bring them to justice.

Similar steps were taken by the Sharia Commission in Al-Dar al-Kabirah in the northern Homs countryside. Earlier this month, it approved sanctions against the owners of arms and shooting. It also demanded that all factions compel officers not to carry arms unless they go to the checkpoints.

The Commission’s decision stated to punish the shooter whether during celebrations or not to get their arms confiscated for 15 days and pay a fine of 150 thousand Syrian pounds, and in case of repeated violations, the weapon is confiscated for 30 days with a fine of 300,000 pounds.

Other attempts were made by the Free Army in Daraa. In the middle of last year, Ahrar Nawa Division which is affiliated with the Southern Front factions in Daraa, banned the sale and purchase of arms in Nawa city, under legal liability and fines.

It also closed all shops and centers for the sale and purchase of ammunition and weapons, and prevented its circulation “under penalty of legal accountability and financial fine.”

In this context, the head of Dar al-Adel court in Hauran, Ismat al-Absi, believes that controlling the random use of weapons is possible only by controlling arms sale.

Al-Absi added in an interview with Enab Baladi that “there is a tendency to control and limit the factions’ use of weapons, and this can happen if there is cooperation and an organized police service, and then the sale of weapons to civilians becomes conditional upon a license, which prevents suspected and unqualified people to take up arms.”

Awareness campaigns … “the least we can expect”

The applicability of certain laws and decisions regarding the use of weapons control in the opposition-controlled areas varies according to the security situation, the specificity of the region in terms of the dominant factions and the nature of the volatile fronts.

According to Brigadier Adeeb Chlaf, head of the Free Police in Aleppo, attempts to control weapons in Aleppo date back to about four years, but they did not work out because most people’s areas are close to the fronts, which forces them to use it in case of “self-defense.”

“In the recent period, we have resorted to awareness campaigns among civilians, and we have issued banners and brochures, in which we asked the armed officers not to use or carry their weapons among civilians,” Brigadier General Chlaf said to Enab Baladi.

Brigadier General Chlaf confirmed that there is positive interaction with the Free Police by civil society organizations and local councils. He said “When there is an incident, and we verify the identity of the gun user, he is arrested, brought to justice and reported to the military commander in his group, and there is cooperation among factions in this context.”

The Idlib Free Police led similar awareness campaigns. In May, a campaign called “Don’t kill me when you celebrate” was launched in an effort to reduce the shooting at social events and urged civilians not to use weapons randomly.

Civil Defense official within Idlib, Yahya Arja, believes that awareness campaigns should be accompanied by practical steps and stresses the importance of “disarming civilians and imposing license conditions.”

Who will disarm civilians and the military after the end of the war?

The “weapons mess” problem raises some issues about the future awaiting the “armed Syrian society”, where the most important question is: how will disarmament be and who will control the licenses?

Commenting on this, Syrian jurist Bassam al-Ahmad, director of the Istanbul-based “Syrians for Truth and Justice” explained that the issue was internationally organized according to the United Nations Peacekeeping Operations, through a program known as “disarmament, demobilization and reintegration (DDR).”

Al-Ahmad said to Enab Baladi that the aim of the program is that the state and its institutions restore monopoly of weapons, so as to ensure stability and security in the community and create an atmosphere of trust among citizens.

The United Nations considers the disarmament, demobilization and reintegration process to be crucial elements in both the initial stabilization of the shattered communities and long-term development processes as part of a comprehensive peace-building plan.

According to the DDR program, ammunition, explosives, light and heavy weapons are taken from combatants and, often, from the civilian population, documented, identified and then disposed of.

“Demobilization” refers to the official removal of actual combatants from the armed forces and armed groups, and includes the “re-annexation” phase, which provides short-term assistance to former combatants.

The United Nations defines “reintegration” as a process in which ex-combatants acquire civil status and receive sustainable employment and income, in compensation for the interruption of their livelihood when they are combatants. It is a socio-economic and political process with an open time frame that is mainly carried out in communities at the local level.

The human rights activist Bassam al-Ahmad pointed out that the previous steps must be taken within a “legal framework” that requires everyone without exception to abide by it and work to control the processes of disarmament from the ground up.

if you think the article contain wrong information or you have additional details Send Correction

النسخة العربية من المقال

-

Follow us :

Most viewed

- Hidden aspects of Iranian consulate building targeted in Damascus

- Russia establishes third military post on borders of occupied Golan Heights

- Elimination of zeros from the Syrian currency: Adverse effects on a collapsing economy

- Why Russia deployed military posts on borders of occupied Golan Heights

- Stigma of Islamic State haunts fighters' families

A

A

A

A

A

A

More In-Depth

More In-Depth