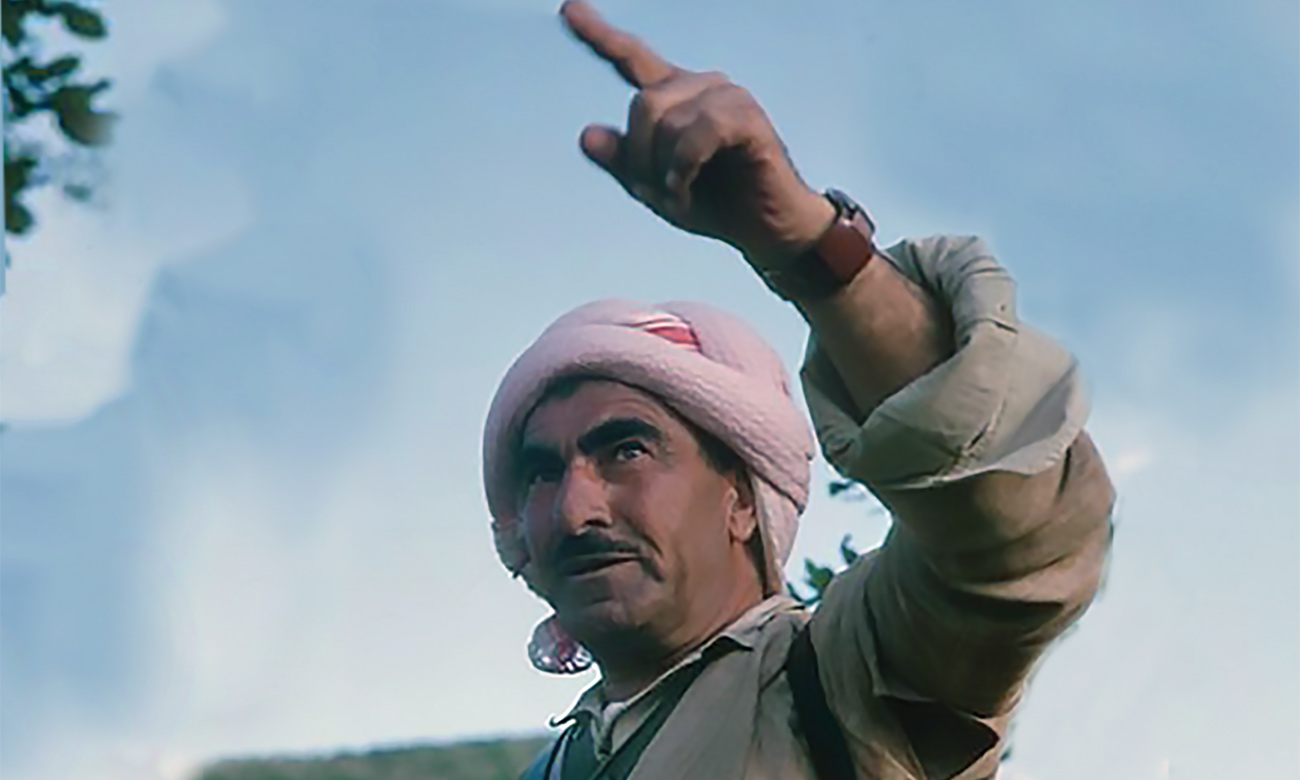

Mustafa Barzani, a Kurdish leader from northern Iraq

Enab Baladi

Although the appearance of the first Kurdish party in Syria dates back to 1957, Kurdish political activity actually dates back to the 1920s and 1930s, a period when several Kurdish associations and organizations appeared on Syrian territory. They portrayed themselves as cultural, social and even sports organizations as a way of covering up their political programs, which faced huge repression not only by the French Mandate authorities but also by Kurdish feudalists. The most prominent of these was the Khouiboun (Independence) Society founded in 1927. Most of these groups were seeking to participate in the Kurdish movement in neighboring countries.

After Syria’s independence from the French mandate, pressures exercised by the Arab Socialist Ba’ath Party, the Syrian Communist Party and the Syrian Social Nationalist Party on small Kurdish political groups spread throughout Syria’s al-Jazira province and the cities of Aleppo and Damascus, increased in light of fears of “separatist tendencies” embraced by intellectual currents in a number of those groups. However, the political vacuum in Syria during the 1950s, which was caused by successive coups against governments, provided an important opportunity to form the first nucleus of Kurdish party activism in Syria. A group of Kurdish intellectuals began organizing the first meetings for the founding of the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) in Damascus, away from the authority of the feudal “Aghas” (a title given within tribal Kurdish society to tribal chieftains) who Kurdish intellectuals accused of trying to suppress the national spirit, in the hope of establishing an umbrella body for intellectuals. Osman Sabri and Abdul Hamid Darwish co-founded the Society for the Revival of Kurdistan in 1955 in Damascus, along with Rashid Hamo, Shaukat Hanan and Muhammad Ali Khoja, who founded the Secret Cultural Society in Aleppo in 1951, as well as Hamza Noiran, the most prominent figure among those who formed the nucleus of the first Kurdish party.

After the announcement of its foundation on June 14, 1957, the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) succeeded in attracting many supporters as it was the first Kurdish political party in Syria. The newly-founded party, led by its central committee comprising more than ten people, quickly became prominent on the local political scene among Syrian Kurds, especially in areas with a large Kurdish population such as Aleppo, Damascus, Afrin, al-Jazira and Ayn al-Arab (Kobani). After its establishment, the KDP received various requests for affiliation from political and cultural groups such as the Kurdistan Democratic Youth Union in Syria, which was founded in the early 1950s to call for the “unification of the Kurds and Kurdistan”. Another party that joined the KDP was the Kurdistan Freedom Party, which was founded in 1958 after its members, including the well-known poet Cigerxwîn, split from the Syrian Communist Party after it refused to issue the Kurdish party’s statements in the Kurdish language and did not show any willingness to defend the rights of the Kurds, according to research published on the “KurdWatch” website.

The Kurdish Democratic Party’s program is composed of 11 points, with no introduction or historical, social or political explanations, details or narratives about the situation of Kurds in Syria. The party focused on the objective of “protecting the Kurds from the mistakes committed against them and from repression and extinction”. It also considered itself a “progressive and freedom-loving party, which seeks to implement popular democracy in its homeland, Syria”, fight against “imperialist exploitation”, demand the Kurds’ political, social and cultural rights within the Syrian state in the regions of al-Jazira, Kobani and Afrin, and support the Kurdish struggle in Turkey, Iraq, Iran and all oppressed nations to liberate their countries.

The party also targeted all Kurds who it described as “honorable nationalists and democrats who seek their freedom, as forces it relies on in its political and social struggle to remove harmful ideas”, through eliminating illiteracy, educating the Kurds, and recognizing the Kurds’ particular situation, along with forming cultural committees in the Kurdish regions and publishing books, magazines and newspapers in the Kurdish language, as well as translating books and research from foreign languages and working to convince the Syrian government to open additional schools in those areas. The party considered peaceful and socialist governments as its allies.

On the social level, the KDP called for the necessity of educating farmers and persuading the government to grant loans to poor farmers and establish clinics and orphanages through collecting donations from the rich, as well as collecting similar donations for students who could not complete their studies due to financial difficulties.

According to Abdul Hamid Haji Darwish, the current Secretary of the Kurdish Democratic Progressive Party in Syria, the political program of the party changed in 1959 to call for a “united and independent Kurdistan”. In addition, the party’s name was amended to the “Kurdistan Democratic Party in Syria”, but these amendments were later annulled in 1963. The parliamentary elections of September 5, 1961 and the end of the unification of Syria and Egypt are considered among the events that radically altered the history of the Kurdish party, since the party broke through the traditional parliamentary election system that had been in place since the French mandate era, which required each party to nominate a Kurd, a Kurd from an urban area, an Arab-Kurd, an Arab, and a candidate from the Syrian Orthodox Church from al-Jazira. Therefore, the party nominated two Kurdish farmers, a Christian from Qamishli and the head of the electoral list Noureddine Zaza. The military intelligence arrested Zaza and asked him to withdraw his candidacy. However, he refused to do so. The Syrian government then started arresting a large number of the party’s members and supporters. This campaign was preceded by similar arrests of 120 party members, along with Osman Sabri, Noureddine Zaza and Rashid Hamo from the Central Committee. Political differences began to emerge between the founding members, according to the memoirs of the Kurdish writer and poet, Mulla Ahmad Nami.

When the Central Committee’s party members were arrested, Noureddine Zaza disagreed with Osman Sabri on how to deal with the arrests and how to present the party’s objectives. Zaza considered that all detainees must state that the party is a cultural club and not a political party, and that its program did not call for a unified and independent Kurdistan. In addition, he thought that members who were under arrest should have their party memberships frozen, which would deprive the Central Committee’s members of their leadership roles.

Osman Sabri totally rejected these views and insisted on stating the objectives of the party during interrogation and on holding on to his leading role in the party. As a result, the dispute between the two men intensified. At the end of February 1961, the military court in Damascus sentenced the members of the Kurdistan Democratic Party, sentencing Noureddine Zaza to one year in prison, Osman Sabri and Rashid Hamo to a year and a half, and Shawkat Hanan to two years. In addition, the military court sentenced officials in the areas concerned to nine months in jail and sentenced ordinary members to three months in jail.

The differences between the two sides deepened during the second party conference in Damascus in 1962 after the release of all the party’s detainees. Zaza was excluded due to his views. Osman Sabri was re-appointed as a member with full authority and secretary-general of the party. Abdul Hamid Haji Darwish was excluded from the party in 1963 after he was considered to be close to Noureddine Zaza’s camp. A Central Committee was formed, which included Osman Sabri, Rashid Hamo, Kamal Abdi, Khalid Masheyekh, Mohammed Mulla Ahmed, Abdullah Mulla Ali and Aziz Dawood.

The division in the party only became official in 1965, after the declaration of the formation of two parties – the Kurdish Democratic Party in Syria (the left wing) led by Usman Sabri, and the Kurdish Democratic Party in Syria (the right wing) led by Abdul Hamid Haji Darwish.

According to Salah Badreddin, one of the former members of the party, the differences between the two Kurdish parties were limited to three main points, which related to the following questions – “Are the Kurds in Syria considered a people or a minority? Do they have the right to decide their own fate or should they only claim their cultural rights? Is the party part of the Syrian democratic movement and its positions on political and social issues in Syria? Should the party stand with the state or the political opposition in Syria? What is the party’s position towards the Kurdish movement in Iraq? Should it support Mulla Mustafa Barzani or Jalal Talabani?”.

From its formation until 1965, the KDP had not been characterized by a unified structure capable of acting in a homogenous manner. Despite widespread popular support at the outset, the party remained caught in a constant debate over its general principles and political platform based on the fundamental points of contestation mentioned above.

Some Kurdish politicians attribute these differences to the clear political contradictions between communists in leading positions in the party on one hand and local notables, landowners and members of the aristocracy on the other hand. Personal differences also existed between leading figures in the party in addition to the impact of the arrests of founding members on the Central Committee in 1959 under the unity government between Syria and Egypt, the departure of other leaders outside the country and the wave of mass arrests in 1960.

In 1970 and at the request of Mustafa Barzani, the Nawperdan conference was held in Iraq with the aim of unifying the two parties and forming a unified leadership. However, this led to further disintegration and to the formation of a third current, the Kurdistan Democratic Party of Syria (PDKS).

An examination of the political agendas of Kurdish parties since the founding of the Kurdistan Democratic Party of Syria in the period from 1957 and 1990 reveals the absence of any claims for the establishment of an independent state for Syrian Kurds. Kurdish parties in Syria did not take up arms in order to obtain their demands or achieve their goals, unlike other Kurdish parties in Turkey and Iraq.

All Kurdish parties that emerged during this period, as stated in their political programs, aspire to “solve the Kurdish issue through democratic measures within the framework of a united Syria”. Hence, the core of these aspirations was centred on “the constitutional recognition of the Kurdish people as the second nation in the country and as a people who have historically lived on their land”. The demands of Kurdish parties in relation to the forms of governance in their areas range from “autonomous administration” to “autonomous government”. These parties call for adequate representation of the Kurds in judicial, legislative and executive institutions according to the percentage of the Kurdish population within the local population, in addition to granting them cultural, political and social rights.

The political programs of these parties also focus on ending all “racist and chauvinistic” practices against the Kurdish people in Syria. They also call upon Kurdish parties at the national level in Syria to implement “democracy in the country”, in addition to “free and fair elections, the separation of powers, freedom of opinion and assembly, as well as the adoption of a modern party law, equality between men and women and the separation of religion from the state”.

However, the organizational structures of most Kurdish parties clearly contradict their own democratic orientations and their demands. Most of the successive schisms between the parties are largely driven by personal disagreements and most have been unable to internalize an internal culture of dialogue before resorting to party splits.

The Kurdish Democratic Party: reasons for disagreement and causes of fragmentation

The foundational phase in the history of the Kurdish Democratic Party in the late 1950s was characterized by intellectual instability and various shifts in its objectives and political program. The prevailing political situation did not reflect or serve the basic objectives of the party, paving the way, instead, for disputes between founders and splits. This was described by the Kurdish writer, Mohammed Jazzaa, as “tragic”. Jazzaa is the nephew of Hamza Noiran, one of the founders of the Kurdish Democratic Party in Syria.

According to Jazzaa, the party was founded at a time when a democratic atmosphere prevailed in Syria and nationalist ideas were widespread. The party was formed in response to an objective need, which was to express the demands of the Kurdish people in Syria. However, the differences between its leaders after 1960 and the wave of mass arrests provided an opportunity for disputes to escalate and for various parties to intervene, which aimed at “weakening the role of the party”.

“These parties raised slogans such as ‘the liberation and unification of Kurdistan’ or ‘are the Kurds in Syria a nation or a minority?’. I believe that raising such slogans was not thought through or realistic. Those who created these phrases were aiming to win the sympathy of the Kurdish masses, knowing that populist approaches to winning over public opinion suggest that the views and approach in question are not correct and that the intentions behind them are insincere.”

When asked about the reasons behind the failure of the party’s right and left wings to unify, which led to further division, Jazzaa argued that “some parties lacked the will to achieve unity, along with the element of egoism. As such, some leaders were preoccupied by their self-interest, which meant that they were willing to do anything to achieve their personal ambitions and take revenge against their opponents.”

He added, “In my opinion, the Kurdish issue had a significant impact, both directly and indirectly, in straining the relationship between parties within the Kurdish movement in Syria and domination of their political orientations and positions. This is no secret, whether this domination comes from southern Kurdistan (Iraqi Kurdistan) or northern Kurdistan (Turkish Kurdistan).”

“The biggest factor that played a major role in stirring up disputes and fomenting divisions since the formation of the party is the interference by Syrian security forces in order to sabotage political life and the party landscape in Syria in general, and the Kurdish political movement in particular. This reminds me of a statement by the Communist leader Khalid Bakdash in response to being asked about the causes behind the splits in the Communist Party. He said, ‘First, interference by the US embassy and secondly, the intelligence agencies of our allies’. The Kurdish political movement is no exception.”

Jazzaa views the party’s political programs that were produced between 1958 and 1990 as “not being as developed as they should have been. They needed more depth and less focus on emotional aspects.”

The writer considers that “parties within the political movement did not fulfil their duty to communicate their cause to Syrian society as they should have. Thus, it was characterized not only by feeble communication, but also isolation from the Syrian national scene. The activities of Kurdish political parties were restricted to internal disputes, on the one hand, and conflicts with the security services, on the other.”

In 1946, in the aftermath of the end of the French mandate in Syria just before the declaration of the United Arab Republic in 1958, Kurdish movements were afraid of going public. Although Husni al-Za’im, who became the president of the first Syrian Republic through the 1949 coup d’état, was Kurdish, this made Arab nationalist movements fear the emergence of ethnic polarization and rise of a “Kurdish separatist tide”. Thus, other post-coup governments imposed restrictions on Kurdish political movements, which were confined to socio-cultural activities at the time. In 1956, the opportunity arose to form the nucleus of the first Kurdish party under the presidency of Shukri al-Quwatli and the formation of the Democratic Kurdish Party was announced. However, the United Arab Republic between Syria and Egypt, headed by Gamal Abdel Nasser in 1958-1961, was an early blow to the Kurdish party project due to the campaigns of mass arrests of a large number of prominent figures of the Kurdish Democratic Party.

The opposition to Kurdish political movements continued after the end of the United Arab Republic, as part of policies to “resist the Kurdish trend” adopted by Syrian governments in the early 1960s up until the Arab Socialist Ba’ath took power in 1963.

At that time, a harsh policy was in place regarding the Kurdish political movement, which led to many measures described by the Kurds as “unjust”. According to research published by the Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies in 2013, the exceptional census conducted in 1962 resulted in thousands of Kurds being stripped of Syrian nationality and the launch of the “Arab belt” project in al-Jazira region, which was linked to the rise to power of the Ba’ath Party. These were the most significant measures taken during that period to constrain the Kurdish movement.

After Hafez al-Assad took power in 1973, restrictive measures against the Kurdish population continued including denying Kurds their right to obtain citizenship and restricting the activities of Kurdish parties. According to research by Dr. Ferset Merei, published in March 2014, Hafez al-Assad succeeded in winning over the leader of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), Abdullah Ocalan in 1980, and provided him with training bases. The Syrian president aimed to put pressure on Turkey in relation to the issue of the decreasing water flow in the Euphrates, in exchange for providing a margin of freedom for Kurdish political parties. This period marked a “semi-official declaration” of “he end of clandestine political action for the Kurds in Syria.

By 1990, there was strong Kurdish participation in the Syrian parliament, with six Kurdish representatives entering parliament. This later rose to 38 members of parliament.

Straight colonial lines drawn on a map established the new Syrian entity and other entities as dictated by French-British interests. The boundaries of the Ottoman Empire were altered several times just after the end of the First World War (1914-1918). As a result, Syria was, in accordance with the San Remo Conference in 1920, placed under the French mandate, while the boundaries of the Ottoman Empire under “Sykes-Picot” were continuously amended. Each of these amendments affected Syrian Kurds. The 1921 Ankara Agreement, which was signed between France and Turkey, mandated the disarmament of the Kurdish tribes in Syria in order not to disturb the Turks.

There were no official legal prohibitions preventing the Kurds from communicating between the two sides of the indefinite sides (unsecured) border. Kurdish nationalists were able to move from Turkey to Syria, individually and collectively, asking France to protect them in light of the active Kurdish national movement in Turkey and persecution and repression on the Turkish side. The failure of the “Sheikh Said” rebellion of 1925 only exacerbated the problems facing the Kurdish nationalist movement on both sides of the border. The Kurdish struggle for rights continued, as did the struggle of the Arabs and Turks, in rejection of the 1919 Lausanne Treaty, which preceded the “Sheikh Said” rebellion, and which led to the recognition of Turkey as an heir to the Ottoman Empire in Anatolia and Eastern Thrace (the European part of Turkey) at the expense of the peoples and minorities whose rights had been recognized by the Sevre Treaty of 1920, which was annulled.

The nationalist currents among the Arabs and the Kurds emerged around the same time, and began to grow and develop, in parallel to the current led by senior Turkish military officers. Arab countries and Kurdish cities witnessed budding nationalist movements that led to revolutions and the emergence of associations, clubs and federations. In Syria, Kurdish nationalists worked ceaselessly to create a national revival and were active in establishing clubs, federations and associations starting from the “Khoiboon” society in 1927, which was established in Lebanon by Kurdish tribal leaders, landowners and princes. Given the limitations of space, we will mention only the most prominent associations, federations, magazines and clubs established between 1927 and 1957, the date of the establishment of the first Kurdish party for Syrian Kurds. The Association for Cooperation and Assistance to Poor Kurds in al-Hasakah, the Hevi Association (Hope), the Kurdish Youth Association in Amuda and others were established. This continuous sense of national awareness on the part of Syria’s Kurds contributed to the formation and launch of the first Kurdish party in 1957.

The party grew up with significant support from Kurdistan, such as the contribution by Jalal Talabani and Abdullah Ishaqi, who were in Damascus at the time, and with the approval and support of the Kurdistan Democratic Party and its leader, Mullah Mustafa Barzani.

The party was welcomed by the Kurdish people and its membership began to grow and the party’s activities expanded. However, the party’s opposition to the policy of establishing a united government between Syria and Egypt and its refusal to dissolve itself led to the arrest of most of its leaders in 1960 following a large security crackdown. In prison, disagreements emerged between the two leading figures of the party, Osman Sabri and Noureddine Zaza, over their response to questions by the military investigating judge regarding the party’s identity and whether it was a party or an association. These disagreements grew, leading to the dissolution of the party for the first time on August 5, 1965 and the establishing of the Kurdish left and right wings.

With the disagreements intensified, the Kurdish leader Mustafa Barzani summoned the two parties to the dispute and invited independent figures to the area of Nawperdan in Kurdistan. In short, the two parties became three parties instead of unifying within one party, with the emergence of a third party due to the first split, which was known as the “interim leadership” or “the party”, which was loyal to Barzani. Between 1965 and 1991, splits took place within the leftist party, while the parallel party, the Progressive Kurdish Democratic Party in Syria, maintained its organizational unity during that period and “the party” also witnessed splits. The Kurdish party landscape witnessed a series of organizational splits during this period, due to the absence of democratic institutions and interventions by Kurdistan, along with encouragement by the Syrian security services, which adopted the policy of “divide and rule” to weaken the Kurds and their political movement. Despite the attempts at unification, most of them failed.

During this long period, party members of different orientations suffered from various forms of persecution as a result of their resistance to the racist and discriminatory policies that affected Syrian Kurds alone, such as confronting the racist exceptional census of 1962, which led to thousands being stripped of their Syrian nationality, and the Arab Belt Project, which aimed at changing the demographic makeup of Kurdish areas and interfering in their structures. The Kurdish movement’s members represented large numbers of those detained in Syrian prisons, especially during the United Arab Republic, its disintegration and the period of Ba’ath rule.

He was born in 1905 in the village of Narince in the Turkish Kahta region. After he moved to Syria, he participated in the activities of the Khoiboon Society and helped establish the Kurdistan Club in Damascus in 1938. He was one of the most prominent founders of the Kurdish Democratic Party.

In 1965, he became secretary-general of the leftist faction after the KDP split, before retiring from party activism in 1969.

During the course of his political life, Osman Sabri was arrested 28 times in Turkey, Syria, Iraq and Lebanon, according to Kurdish historians. He also called for the “revival of Kurdish culture” and encouraged the conversion of the writing of the Kurdish language to Latin characters. He wrote several works, including “The Storm”, “Our Pains” and “A Latin Kurdish Alphabet”.

He was born in 1919 in a Turkish village and completed his intermediate studies in Diyarbakir. He was among those displaced who came to Syria in 1938. He received his Bachelor’s degree in political science from the French University in Lebanon and received a Doctorate in philosophy from a Swiss university in 1956, before returning to Syria and participating in the founding of the Kurdish Democratic Party in Syria in 1958.

Noureddine Zaza ran for parliamentary elections in 1961 but was arrested by Syrian security forces. After his release, he traveled to Lebanon and returned to his home country in Turkey in 1976. He was prosecuted in Turkey, which led him to return to Switzerland.

In Switzerland, he published a book, “My Kurdish Life” in 1982, and passed away in 1988.

He was born in 1925 in the village of Hubka near the city of Afrin. He was unable to complete his studies as his family was poor, which later drove him to establish a school for young children in the villages of the region. He then founded a school in Afrin and oversaw its management until it was closed in 1951 after his arrest in Damascus due to his participation in the establishment of a Kurdish cultural association.

He joined the Syrian Communist Party in 1952 and then participated in founding the Kurdish Democratic Party in Damascus.

In 1959, he was arrested by Syrian security forces and placed under house arrest for several months. He was re-arrested in 1964. After his release, he traveled to Turkey on the instructions of the party, with the mission of helping the Kurdistan Democratic Party there.

In 1970, Mustafa Barzani appointed him editor of the Al-Kader magazine in Baghdad, where he continued his work for seven months. He retired from political activism in 1993 to devote himself to intellectual, cultural and social work.

if you think the article contain wrong information or you have additional details Send Correction