Enab Baladi – Investigations Team

It is difficult for centers on documentation and statistics or human rights organizations to have accurate statistics in wartime Syria, in light of the regime’s policy of refusing to publish any demographic data since 2011, as well as the division of control and power between different forces throughout Syrian territory, including the province of Homs, which has the largest number of cases of displacement.

The preparation of this report coincided with preparations to evacuate the last group of displaced persons from al-Waer neighborhood, the last opposition-controlled neighborhood in Homs. The report came up against many difficulties in identifying the numbers of displaced persons from Homs and its countryside, although we recently received estimates from various human rights and media sources,

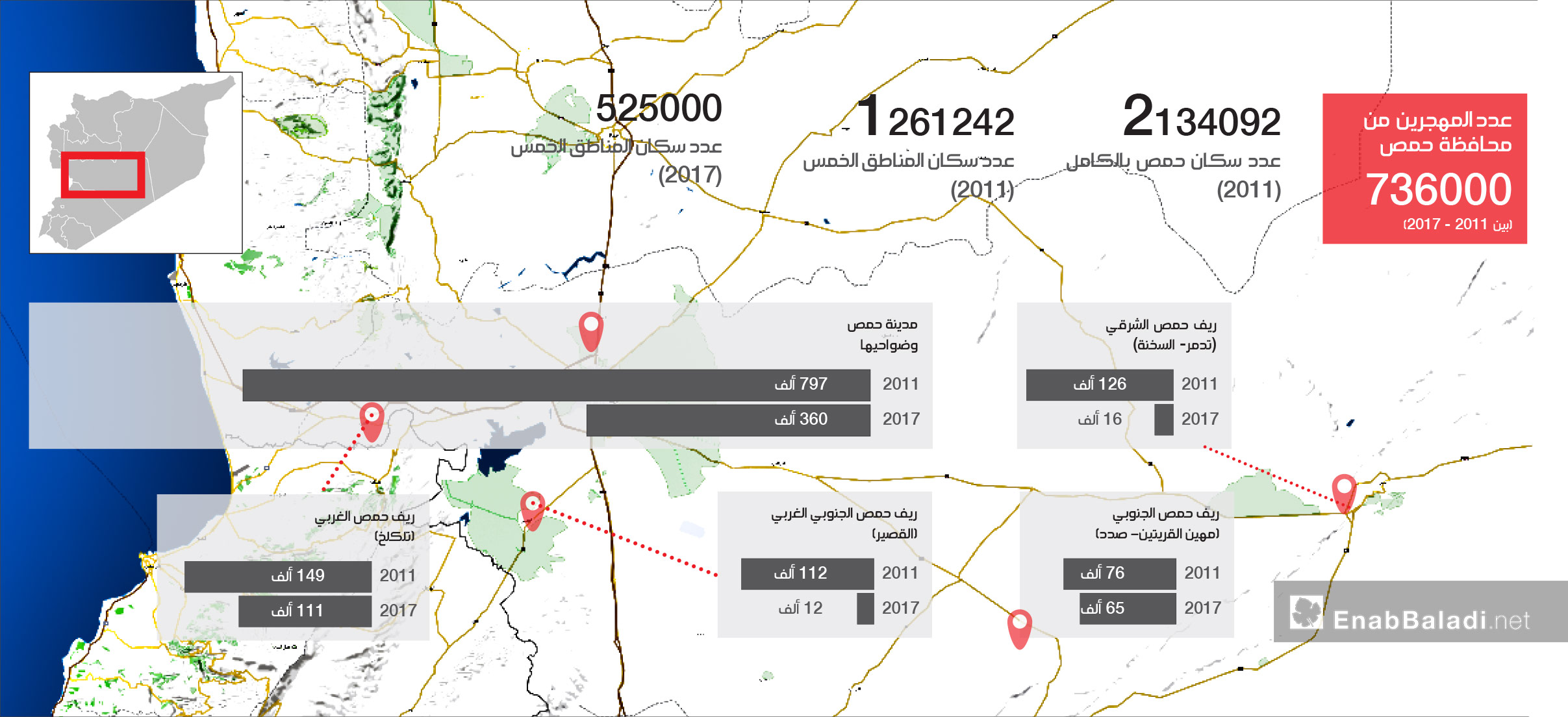

The Enab Baladi team has been monitoring five specific areas of the province that have been subjected to forced displacement or outright displacement over the past five years. The pre-war population of these areas was 1,261,242 inhabitants out of a total of 2,134,092 inhabitants of the entire province, according to Decision No. 1378 issued by the Ministry of Local Administration in 2011, which we will refer to as the “2011 census”.

Take me to Homs!

With a look of complete concentration and nostalgia on his face, Muhammad gazes at his computer screen and opens Google maps. He visits Homs through satellite images, walking around its neighborhoods, looking at length at his neighborhood and home, hoping that this might heal his sense of longing.

Although he insisted on staying in his house and not leaving his neighborhood during the most difficult and bloody days witnessed by the two neighborhoods of al-Inshaat and Baba Amr, Mohammed (which is not his real name), an electrical engineer from al-Inshaat neighborhood in Homs, was forced to do so two years later, like many hundreds of thousands of other residents of Homs.

“Despite the very dangerous situation, my family and I did not want to leave. All the houses in the building we lived in were empty, only our family had stayed. We saw from our balcony families forced to leave due to the military escalation in Homs. Every time we saw a family leave that we knew, we were wondering, ‘When will our turn come?’. I had only one friend left in Homs, all the rest have left Syria. Most of the buildings in our neighborhood were empty. The streets of al-Inshaat neighborhood were full of tanks and military vehicles instead of cars. This was in early 2012, during the military campaign on Baba Amr neighborhood”, Mohammed said.

Mohammed’s family lived through the war with great cautiousness, staying at home all the time expect when going out to buy basic necessities. He says, “The sniper on Hanadi tower did not spare a single moving target. There were often people injured or martyred right in front of me, by sniper fire. So staying at home meant staying alive. Here, I’m not talking about the possibility of getting hit by shells, missiles and bullets inside the house. That’s something we can’t avoid, especially since our house is on the fourth floor. Sometimes, after becoming almost deaf due to the sounds of shells and aircraft, I used to stay at a neighbor’s house in a nearby building, because it was on the ground floor.”

By the end of 2012 and during 2013, Homs began to witness stable conditions and some families began to return. In 2014, Mohammed decided to complete his university studies. He continued, “After two years of staying at home, I decided to continue my university studies. I managed to pass the remaining subjects in my 4th year, hoping to graduate the following year but all of this was shattered in one moment.”

In October 2014, while he was trying to register for the final year of electrical engineering, the registration officer at al-Baath University told the Mechanical and Electrical Engineering Department that he was not eligible to register because he had used up all his chances to repeat the year.

He explained, “The employee told me that I was not eligible to take exams for the fourth year because I had used up all his chances to repeat the year. Even though I was registered to sit the exams since my name was listed in the official papers and the fact that I had passed, my registration was considered invalid. So, in the blink of an eye, I was stripped of my successful exam results and of my status as a fifth-year student. Even worse, they contacted the conscription division to cancel the postponement of my military service, which I had obtained based on being in my fifth year.”

Mohammed consulted a lawyer hoping to find a way out of his situation, “The lawyer told me that the university has recently become stricter in scrutinizing files due to the large number of forgeries. If an employee makes any legal mistake, he would be punished but the student does not benefit.”

The lawyer told Mohammed that it would only be a matter of time before he would be called up for military service. Thus, he found himself obliged to contact a driver who could take him to Lebanon so he could travel from there to Turkey.

From Turkey, two and a half years after he was forcibly displaced from the neighborhoods of Homs, Mohammed gazes at the city of Homs on a map and in the pictures that his family sends him from time to time. He adds, with sadness in his voice, “The real loss is to be away from my family. I have no hope of returning. I don’t want my family to go through the experience of being a refugee and living in exile. Turkey’s restrictions on visits and visa problems have made things even more complicated and reduced the chances of being reunited with the family.”

The city of Homs: The first appearance of the green buses

The neighborhoods that witnessed a total displacement of civilians in the city of Homs include the neighborhoods of the Old City (14 neighborhoods inside the wall), as well as the neighborhoods of al-Khalidiya, Baba Amr, Deir Baalba, al-Bayada, al-Ashira, Karm al-Zeitoun and Jib al-Jandali in the eastern part of the Old City.

The first scene of “forced displacement” was the Baba Amr neighborhood at the beginning of the revolution. This neighborhoods was the first in Homs to witness armed conflict in 2012. It was besieged for more than 25 days before the al-Assad forces asserted complete control over it, evacuating all civilians there to nearby neighborhoods in February 2012. The deportation was executed as part of an agreement that allowed the locals to leave in exchange for handing over the corpses of Syrian Army officers who were killed during the military confrontations.

According to the estimates of a resident from the neighborhood obtained by Enab Baladi, the number of Baba Amr’s inhabitants before the Syrian revolution was fifty thousand. Only 10% of them have returned in the years that followed the Syrian regime’s takeover.

As for the remaining neighborhoods in Homs, the Bab al-Sebaa area, which includes Ashira, al-Nazihin and Karm al-Zaitoun, in addition to the areas of al-Mreja and Rabiʿa al–Adawiyya, witnessed the first scenes of forced displacement in Homs following the massacre of Karm al-Zaitoun in March 2012, in which dozens of women and children were killed.

Bab al-Sebaa was only the beginning of a wave of forced migrations from Homs, which also affected Deir Baalba, al-Bayada and Jib al-Jandali. Al-Assad’s forces imposed a siege on the old neighborhoods of the city such as al-Khalidiya, Bab Tadmor, Bab Houd, and al-Kousour and other well-known neighborhoods “inside the walls” of Homs, which were completely emptied of civilians in May 2014. The civilians were taken to the countryside north of the city under an agreement between the opposition and the regime, sponsored by Iranian officers. Green buses were used for the first time in the displacement process.

The population of the city of Homs was about 761,850 people, according to the “2011 census”. However, Enab Baladi conducted another approximate census in early 2016, based on figures provided by the heads of the city’s neighborhoods. This census showed a decline in the population to about 629,000 people, with a difference of 132,700 compared to the initial figure.

In al-Waer Neighborhood, the Syrian regime and its Russian allies put an end to the policy of deportation in the city of Homs after four years of siege. During this period, the al-Assad forces and its supporting militias used medium and heavy weaponry as a means of exerting pressure, as it did in other towns in Homs. The operations ended with the total evacuation of the neighborhood following an agreement between the two sides, sponsored by Russia.

In the statistics obtained by Enab Baladi from activists in al-Waer neighborhood, the population of the neighborhood at the beginning of the Syrian revolution in 2011 was around 100,000. The population increased to 280,000 during 2013 and 2014 after the displacement of civilians to the neighborhood from the old neighborhoods of Homs.

In early 2014, during the first military campaign by the al-Assad forces on the neighborhood, an agreement was reached to evacuate a number of civilians to the countryside north of the city. Subsequently, the population declined to 100,000 again. This number gradually fell until it reached 40,000 inhabitants at the beginning of this year. Under the abovementioned agreement, approximately 25,000 people left the area, in addition to the groups that left recently.

According to these statistics, it is estimated that less than 8000 people remain in the neighborhood, including students, the elderly and employees. They represent around 19% of the neighborhood’s population in general, in addition to 23% who left for neighboring districts and 58% who headed to northern Syria. In effect, the total population fell from 280,000 in 2013 to 8000 by the end of May 2017.

According to this data, the city of Homs has lost 404,700 civilians from all its neighborhoods, which means around 50% of the city’s overall population.

The southern suburbs of Homs, namely al-Naqirah, al-Mubarakiya, Tal al-Shor, Jobar, Kafr Aya, al-Sultaniyah and Ain al-Zarqa, which contain 35,664 civilians, according to the 2011 census, also witnessed mass displacement operations. These resulted in total evacuation of these areas by al-Assad forces, due to their proximity to areas witnessing the biggest military clashes. These regions also welcomed migrants from al-Qusayr during that period, in addition to being a base for a number of fighters belonging to Free Army factions.

Enab Baladi spoke to a displaced resident of the area (who asked not to be named), who explained that only three houses remained intact in al-Mubarakiya out of 2500 houses, and that there were no residents left in the area. The local added that Kafr Aya, Jobar, and al-Naqirah as well as all the old suburbs of Homs have not seen their former inhabitants return after they left at the beginning of the revolution.

Talkalakh: The sectarian nature of forced displacement

Talkalakh is located in the western countryside of Homs, close to the Syrian-Lebanese border. The city of Talkalakh contains many towns and villages, the most prominent of which are al-Zarah, Akari, al-Hisn, and al-Hawash, in addition to other areas. It is considered a region of religious and sectarian diversity, with a Sunni majority and significant Christian as well as Alawite communities in the countryside. According to the 2011 census, the region has a population of around 149,000.

Talkalakh was drawn into the conflict in Syria from the beginning of the revolution against the Syrian regime. The region witnessed an escalating protest movement that was met with violence and oppression by the al-Assad forces and militias, which are essentially sectarian, according to the Syrian Network for Human Rights.

The conflict reached its peak in 2013 after the Syrian regime regained control of the city of al-Qusayr and its surroundings (in the south-west of Homs), with the official decision by Hezbollah to enter into the conflict in support of al-Assad’s forces. The Syrian regime gained control of Talkalakh in June 2013, and then regained control over the town of al-Hisn in March 2014 after a series of battles that were accompanied by a massive wave of emigration by civilians.

Enab Baladi spoke to Muawiyah Dandashi, a doctor and human rights activist from the city of Talkalakh who is currently residing in Saudi Arabia. He revealed unofficial local statistics concerning the population rate in the region and explained that the displacement in Talkalakh only targeted the Sunni population of over 58,000 people, mostly inside the city and in al–Zarah and al-Hisn .

Dandashi explained that, according to local statistics collected by human rights activists in Talkalakh, 65% of the Sunni population in the region has been displaced, a total of approximately 38,000 people. Most of them sought refuge in Lebanon, some moved to Turkey and Europe while others migrated to calmer areas of Syria.

Enab Baladi contacted a source in the UN High Commission for Refugees in Lebanon, who explained that 12,000 people registered in the personal status division of Talkalakh are now refugees in Lebanon.

Displaced on foot from al-Qusayr

In recent years, the city of al-Qusayr, in southwestern Homs, has often been overlooked among the wave of agreements to displace residents of Syrian cities, despite the fact that it was the first city where civilians displacement convoys were initially launched by the Syrian regime and its supporters. The Syrian regime has maintained a policy of “self-legitimization” to exert full control over the targeted cities.

In early 2013, al-Assad’s forces cooperated with Hezbollah to launch an attack on the city from three fronts after they had taken control of surrounding towns and cities with a Sunni majority such as Tell al-Nabi Mando, al-Dabaah, Wadi Saleh, Diba, Arjoun and Jusiyah. Al-Assad wanted to deal a final blow to the Syrian opposition factions inside the city, in line with Hezbollah’s desire to “purge” the Syrian areas bordering Lebanon and to place the area under its control.

Al-Assad’s forces and the Hezbollah militia used all kinds of weaponry, along with concentrated aerial bombardment, to launch a major attack on the city and its surroundings. This initially led to the intermittent displacement of civilians due to the aerial bombardment that was part of the military offensive in early 2013.

This was then followed by “forced” displacement during the second military campaign in May, which led to al-Assad’s forces asserting full control over the city and the loss of control by opposition factions.

Al-Qusayr is considered one of the largest cities in the province of Homs. It contains more than 80 villages, most of which have a Sunni majority, along with villages containing Christian, Shiite and Alawites communities. The population of the region is estimated at 111,969, according to the 2011 census.

However, statistics concerning the region’s population after civilians left in the aftermath of the military invasion are not precise. According to media activist Hadi al-Abdullah who is originally from al-Qusayr, the displacement operations focused mainly on Sunni villages and on 90 percent of the residents of al-Qusayr. He pointed out that “the number of displaced people from al- Qusayr and its rural areas who were displaced due to Hezbollah’s entry is over 100,000”.

There were no green buses at the time, according to al-Abdullah, so the city’s residents walked 35 kilometers in the direction of al-Qalamun in the beginning. They spread out among various Lebanese refugee camps while another group went to the north towards the countryside of Aleppo and Idlib.

The media activist attributed the lack of attention paid to the city of al-Qusayr among Syrian cities experiencing displacement to the fact that it was “the first to witness displacement operations, in a manner that was not official like cities now. It was considered instead as a case of al-Assad establishing his control, causing citizens to leave towards safe areas at a time when green buses had not yet made an appearance.”

Civilians are victims of the conflict between ISIS and al–Assad in southern countryside of Homs

The city of al-Qaryatayn and the two towns of Mahin and Sadad are located in the southern countryside of Homs, close to the administrative border of al-Qalamun in northern Rif Dimashq. The three adjoining areas witnessed fighting and battles that resulted in the displacement of the local population, which was estimated at 76,500 according to the 2011 census.

According to a report issued in November 2015 by the Syrian Network for Human Rights, around 20,000 people have been displaced from Mahin town alone in the course of the battles between the regime and ISIS. Other sources indicate that no one has returned to the town due to widespread destruction and fear of the tight security grip by the regime, which is currently in control of the town.

The city of al-Qaryatayn and its surrounding countryside also experienced displacement after the Syrian regime regained control in April 2016. Local media sources indicate that 50% of the city’s residents – estimated at 40,000 according to the 2011 census – have been displaced and none of them have yet returned.

This also applies to Sadad, a Christian town that had 16,500 citizens according to the 2011 census. The town risked being overrun by ISIS in late 2015 and around 10,000 people, mostly children, women and elderly people, left for neighboring Christian villages such as Fairouzeh and Zaidal and others to Damascus, according to statements made by the former mayor, Suleiman Khalil.

The bride of the desert left without inhabitants

The city of Palmyra, which lies in the eastern countryside of the province of Homs, contains several villages and towns, most famous of which is al-Sukhnah situated to the east, whose population is estimated at 126,187, according to the 2011 census.

Control over Palmyra has rotated between al-Assad’s forces and ISIS over the past two years. It was the scene of large-scale military operations involving foreign and local militias and Russian ground and air forces. This resulted in waves of emigration by residents until Palmyra became completely empty. Meanwhile, al-Sukhnah, which is still under ISIS control, contains a few hundred families who are still living there.

Enab Baladi contacted the Studies and Documentation Center in the city of Palmyra. Based on an approximate census carried out in July 2016, the Center stated that 110,400 people have been displaced from the city of Palmyra and its countryside in waves, starting from when ISIS took control of the city in May 2015.

Until now, none of the city’s displaced residents have returned. They have dispersed among areas of Syria under the control of different groups, as well as border camps along the border with Jordan and Turkey. Nasser Abdel Aziz, the Center’s director, said, “So far, only 50 people from the regime have returned to the city.”

Opinion poll

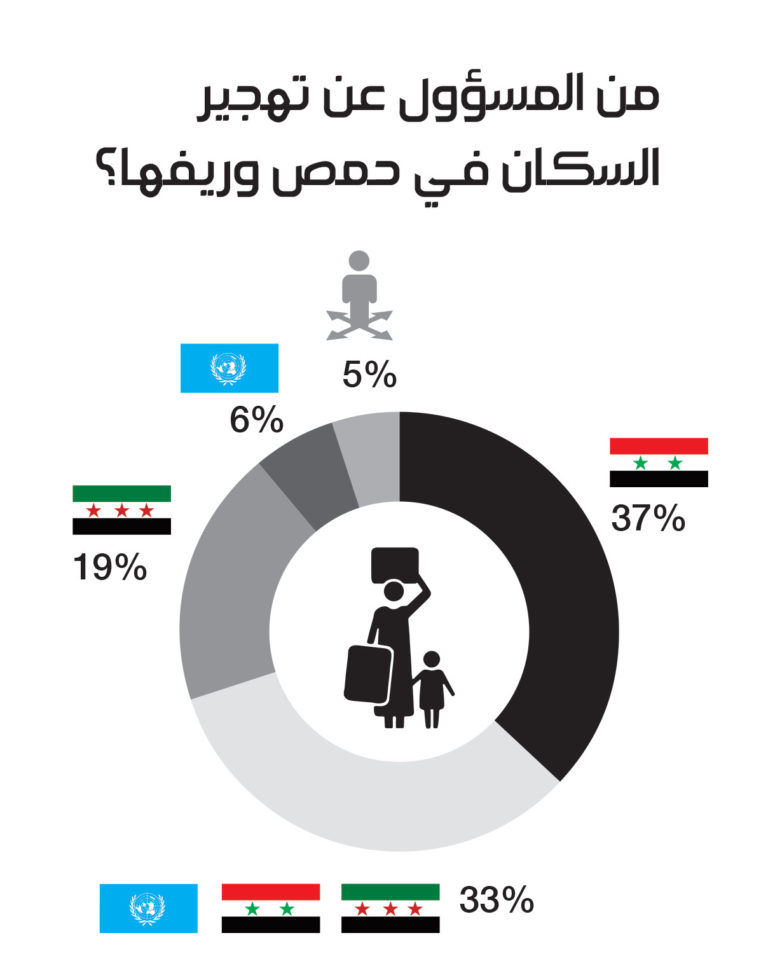

Enab Baladi conducted an opinion poll on its website between May 18, in which 411 people took part as of 1 p.m. on Saturday, May 20. The question posed was: “Who is responsible for the displacement of residents of Homs and its countryside?”.

The poll showed that 37% of the participants blamed the Syrian regime and its militias for the displacement, while 19% held the political and military opposition responsible, and 6% said that the United Nations and the international community carry the biggest responsibility for the displacement.

Who is responsible for the displacement of residents of Homs and its countryside?

However, around 33% of the participants took the view that the Syrian regime, the political and military opposition, the United Nations and the international community all share responsibility for the displacement in the province of Homs. Meanwhile, 5% considered that the departure of civilians was a choice.

Forced displacement: An exodus of human resources

Walid Fares, a political activist from the city of Homs

In Syria, there is much talk about the demographic changes taking place in the different regions of the country. Everyone is worried about the changing local ethnic balance, which in turn affects the regional balance. From this point of view, this is a real issue. However, what is not being mentioned is the continuous exodus of the Syrian people at the level of individuals and institutions.

The human resources that have been developed intellectually and physically in Syria in various fields have received much attention from the countries receiving refugees since the early months of the Syrian revolution. For example, the statistics of the Syrian Doctors Union indicate that there were 3000 doctors in Homs alone at the beginning of 2011. Now, there are fewer than 300. This applies to teachers, lawyers, engineers, economists, administrators, and even those who are self-employed.

According to the Syrian Central Bureau of Statistics’ figures, the population of Homs in early 2011 was around two million. Six years later, there are less than 500,000 inhabitants in the entire province.

The sniping, shelling and siege, as well as the horrific massacres committed by Bashar al-Assad’s regime and its militias, led to the forced displacement of more than one and a half million people in the province of Homs.

This is not restricted to Homs alone. After bombing the neighborhoods Baba Amr and Jouret al-Arayes for more than 27 days using various types of weaponry, the regime’s land forces stormed the area and carried out a campaign of arrests and massacres against the few remaining inhabitants. The Shabiha militias then broke into Karm al-Zeitoun and carried out the famous massacre of children, in which more than 25 children were slaughtered.

At the same time, in early 2012, massacres were carried out in the al-Sabil, Bayada, al-Rifai, al-Idawiya and al-Hawla neighborhoods, in addition to abductions from various areas by al-Assad militias and killing in prisons by the regime’s security forces.

Residents are faced with a difficult choice. They risk being killed if they stay in an area controlled by revolutionaries or being slaughtered or killed in the regime’s prisons if they remain after the regime invades their area. They may be forced to leave their houses to go to other areas with less conflict or to leave Syria.

By the end of May, the forces of the regime will be in control of al-Waer neighborhood in Homs after bombing the area, laying siege to it and starving its residents for almost three years. Less than 5000 people remain in the neighborhood (less than 2% of the original population before the siege). Al-Waer neighborhood can be considered an advanced example compared to other areas, that are now completely empty of residents.

In 2013, the al-Assad regime took control of al-Qusayr and the southern villages of Homs, which led most of their residents to leave. Even though nearly four years have passed, these villages remain deserted and empty, with only a few thousand residents left. In the eastern countryside of Homs, ISIS and the regime jointly uprooted more than 90% of the population of Palmyra, al-Qaryatayn, Mahin, and other villages. More than 70% have left the villages in the western countryside of Homs that were under the control of the regime, such as al-Zarah and Qalaat al-Hisn (Crac des Chevaliers).

Residents in Homs are now confined to two main areas – the neighborhoods surrounding the old city of al-Ghouta, al-Malaab, Karam al-Shami, al-Inshaat and others. There is a sizeable decrease in the number of residents leaving for neighboring countries on a daily basis, especially young people escaping compulsory military service and arbitrary arrest carried out by the regime against young people in general. The other main area containing residents is the northern countryside of Homs, which has been subjected to daily air raids and artillery shelling for the last four years. This is pushing the remaining residents to try to look for safer places.

This is not limited to opposition areas only. The pro-regime neighborhoods of Homs have seen thousands of young people leave for other countries in order to escape military conscription in a battle they do not see as theirs. Thus, the exodus of human resources and Syrian capacities continues in the shape of forced emigration, bombardment, arbitrary detention or deployment in the battle to protect al-Assad.

if you think the article contain wrong information or you have additional details Send Correction

النسخة العربية من المقال

-

Follow us :

A

A

A

A

A

A

More In-Depth

More In-Depth