Below the western Qalamoun Mountain Range is the key to “Damascus’ abundance and the secret behind its immortality.” The area is one of only three areas in Damascus’ rural outskirts that remain outside regime control, alongside Eastern al-Ghouta and southern Damascus. These areas continue to resist the regime, especially after al-Assad’s soldiers forcibly displaced the local population from Eastern al-Ghouta and its northern countryside in the name of so-called “reconciliation agreements” based on a Russian plan.

Wadi Barada or Bardyus (“paradise” in the ancient Roman language), according to the Damascene historian Ibn Asakir, is the name given to the geographical area south of the city of al-Zabadani and north west of Damascus where the Barada River originates. The river is the vital artery for one of the oldest capitals in the world and was described by the Greeks as the “Golden River.”

“No flowers for a people who have not known Barada”, wrote the Umayyad poet, Jareer, in his praise of the “sacred” river, and “No life for Damascus without its Fija.” The phrase highlights the importance of the river, which has been proven by events in recent weeks after regime warplanes targeted the Ein al-Fija water plant, cutting off Damascus’ drinking water supply. The attack came as part of an attempt to gain control of Wadi Barada and expel persons “rejecting the settlement” to Idlib.

The village of Ein al-Fija in the Wadi Barada area in Damascus’ rural outskirts (Enab Baladi Archives)

The area of Wadi Barada extends from the southern axis of the city of al-Zabadani and the town of Madaya to the towns of al-Haama and Qadsaya on the western edges of Damascus. The area contains around 20 towns and villages and is famous for its outstanding natural beauty and its abundance of water. Since it is located in a valley between the Qalamoun mountain range, the villages of Wadi Barada belong to the Ein al-Fija district and have a population of around 76,000 residents, according to official statements by the town’s mayor in 2014.

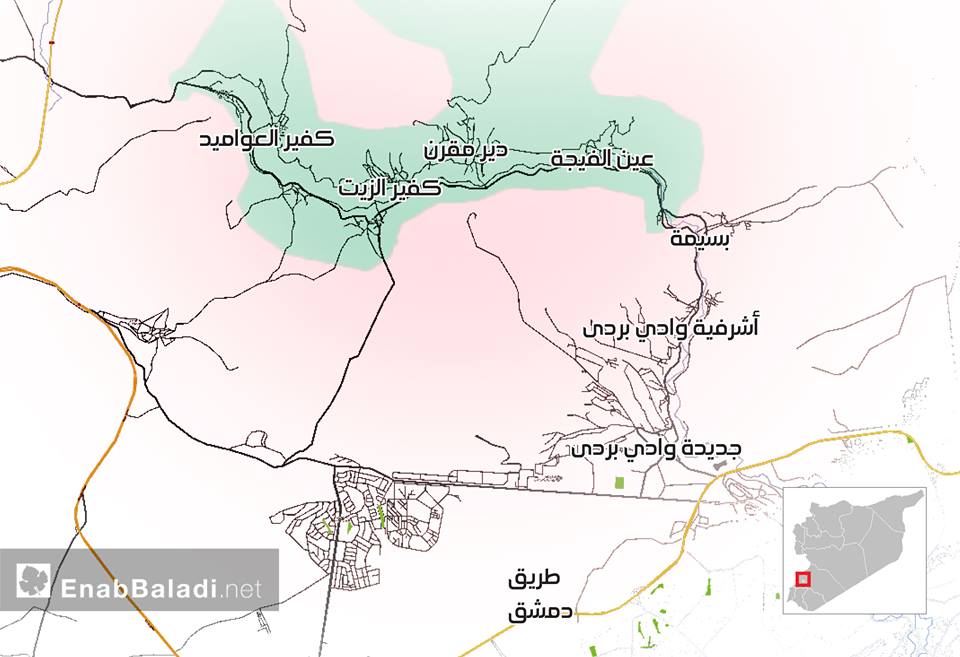

The most prominent towns and villages in the valley include Harira, Afra, Souq Wadi Barada, Burhaliya, Kafr al-Awamid, al-Husseiniyya, Kafr al-Zein, Deir Qanun, Deir Muqran, Ein al-Fija, Ein al-Khadhra, Baseema, Ashrafiyyet al-Wadi and Jadidet al-Wadi.

Ein al-Fija is the most famous area in Wadi Barada and contains the Ein al-Fija water spring source, the main source of drinking water for Damascus and its outskirts. The source springs from the al-Qalaa Mountain, flowing at a speed of 30 metric cubes per second. It is distinguished by its high quality, by international standards.

Most of the villages and towns of Wadi Barada have been under opposition control since 2012 except for Ashrafiyyet al-Wadi, Jadidet al-Wadi and the village of Harira, which recently came under the control of Lebanese Hezbollah.

Damascus’ Artery

Barada River is considered Damascus’ artery as it is the only river that passes through it and irrigates the orchards and agricultural land on the edges of Damascus, enabling the city to attain a “satisfactory” level of agricultural sufficiency. The river is also the only spot for relaxation available to the city’s residents. Many parks were set up along the river’s banks from Wadi Barada until the al-Rabwa area.

Aside from the importance of Barada, the area has special significance as it contains the Ein al-Fija water spring, which is the main source of drinking water for Damascus. We present a brief historical overview of the mechanisms for transporting water to the city based on a detailed report published by the Public Institute for Drinking Water and Public Sanitation in Damascus on its website.

Since ancient times and until the end of the period of Ottoman rule, Damascus depended on running water in addition to drawing water manually from some of the water springs around the city (Ein al-Karsh, Ein al-Fija, Ein al-Zaynabiyya, Ein Ali and others). Residents also depended either on wells dug inside houses from which they drew polluted surface water or on the river water, which was a fertile breeding ground for bacteria. During the reign of the governor Nadhim Pasha, a decision was taken to divert part of the al-Fija source to Damascus using secured pipes and distribute it to fountains dispersed around the city.

The Ottoman Empire launched the project in 1908, distributing the spring water to 400 “sabeels” or fountains around the city. Water would flow in the fountains for an average of two hours every morning and every evening. The water was exclusively used for drinking, while river water was used for household chores. This system remained in use until 1932.

In 1924, the French “Theg” company initiated a study for a project to draw Ein al-Fija water to the houses of Damascus. The project was completed in 1932 and inaugurated after a concrete waterway was built to draw water from the spring to Damascus. Three large tankers were also built and a cast iron water network was installed, covering most of the city’s neighborhoods.

In 1966, Damascus City province began to prepare a new organizational plan for the city to address the city’s expanding needs and its expected population growth until 1984. The institution responsible for water provision participated in preparing the new plan and in conducting a study to provide drinking water for the city based on the plan. The plan sought to ensure optimal use of the Ein al-Fija source.

According to the Public Institute for Drinking Water and Public Sanitation of Damascus, the al-Fija spring is unable to meet the city’s water needs in the long term. The institute recently began searching for additional sources of water in coordination with the Water Basin Directorate in the Irrigation Ministry.

The groups participating in the fighting against the factions in Wadi Barada are the following:

The 4th Armored Division of the al-Assad forces, commanded by Maher al-Assad.

The Republican Guard, part of the al-Assad forces, which controls the hills surrounding the valley.

The Lebanese Hezbollah group, which controls western al-Qalamoun in Damascus’ rural outskirts.

The local “National Defense” militia, which was established in 2013.

The “al-Qalamoun Shield” militia established two years ago, made up of residents of western and eastern al-Qalamoun.”

Revolution in the Valley

The uprising of Wadi Barada against the Syrian regime is not very different from those that occurred in the other cities and towns of Damascus’ rural outskirts. The valley’s villages witnessed popular protests in the first weeks of the revolution, which quickly turned into an armed struggle, leading to opposition factions gaining control of the area in February 2012. The technical and engineering teams continued their work at the Ein al-Fija station.

In November 2013, the al-Assad forces and their allied militias imposed a complete siege on the Wadi Barada area, al-Zabadani and Madaya north east of Damascus. Since then, Wadi Barada has gone through a cycle of truces and repeated breaches, characterized by the struggle over water and peace.

The Wadi Barada area includes several Free Syrian Army factions. The most prominent are al-Sham Substitute Legion, al-Sham Liberation Army, Jaish al-Islam, Ahrar al-Sham Movement and some fighters from the Fateh al-Sham Front based in the northern edges of the valley.

The regime initiated a plan to isolate opposition areas surrounding Damascus in early 2013 by imposing a siege on dozens of cities and villages and striking separate local reconciliation deals. This occurred in southern Damascus, Modhamiyyat al-Sham, al-Tell, Kanakir, Qadsaya, al-Haama and other areas. The same plan was applied to Wadi Barada. The plan aimed to divide opposition areas into small “islands” that would be easy to control.

The al-Assad forces, supported by the Lebanese Hezbollah militia and the local National Defense, tried to storm Wadi Barada repeatedly but all their attempts failed in the face of the opposition factions’ most effective weapon – control over the al-Fija water spring. The factions resorted to cutting the water supply to Damascus more than once in retaliation for every attempt to storm the valley. The confrontations ended with new ceasefires and agreements that restored relative peace to the valley’s villages.

The year 2016 radically altered the balance of power in the areas surrounding the capital. It was the year of displacement starting with Daraya, Modhamiyyat al-Sham, Khan al-Sheikh, Zakya, Qadsaya, al-Haama, al-Tell, Kanakir and Sasa. The areas around the capital were “secured” except for three key areas – Eastern al-Ghouta including its cities, towns and strong factions, southern Damascus, which had been under a truce for two years, and the area of Wadi Barada north west of Damascus. Southern Damascus is in the process of negotiating a “forced” settlement with the regime, which would lead to the forced displacement to Idlib province of anyone who rejects al-Assad’s rule.

The “al-Qalamoun Shield” militia includes fighters from the towns of western and eastern al-Qalamoun. The militia has participated in all the battles in the area, through which al-Assad’s forces managed to regain control of several cities and towns including Yabroud, al-Nabak and Qaara. The militia also participates in fighting on other fronts including in the area surrounding the “T4” airbase in Homs’ countryside and in Hama’s eastern countryside.

Since 22 July 2016, after the al-Assad forces and Lebanese Hezbollah group entered the village of Harira, considered the gateway to the villages and towns of Wadi Barada, the regime and Hezbollah put in play a plan to enter the area, as seen in the campaign that began in the second half of December 2016.

Activists suggest that the campaign on Wadi Barada seeks to bring the area under the control of Hezbollah, since the area is an extension of the al-Zabadani plain where the militia’s forces are concentrated and which borders Lebanon. However, other activists suggest that the regime is the main actor behind the campaign as it seeks to secure the area surrounding the capital and add it to others under its control. This is effectively what has happened in recent weeks, during which the area has experienced “appalling” conditions.

The area’s residents have had to live through repeated attempts to storm the area and extensive aerial bombardment targeting its villages and towns, resulting in the death and injury of civilians. In addition, residents have had to cope with snipers targeting them, as documented by the Islamic Association in the area, as well as electricity and water cuts, a lack of medical supplies, and the spread of disease due to residents drinking water not fit for consumption.

Since the start of the campaign, the al-Qalamoun Shield militia, founded in 2014, began sending reinforcements to fight alongside the al-Assad forces and Hezbollah, as confirmed by images published on social media by activists from the area.

During the campaign, local groups in the valley have warned of the possibility of a “humanitarian tragedy” affecting millions of civilians in Wadi Barada and Damascus in light of the continued aerial bombardment and ground attacks by the al-Assad forces and militias. Despite these warnings, no international actors have mobilized to end the bombardment.

The Syrian regime justifies its targeting of the area based on the presence of Fateh al-Sham Front fighters in the valley, despite its announcement that it is committed to the ceasefire agreement signed under Russian and Turkish sponsorship on 29 December 2016. Since its announcement, the regime has breached the ceasefire hundreds of times in various parts of Syria. These breaches prompted the opposition, which asserted that no faction is excluded from the agreement, to suspend its participation in the Astana negotiations that are expected to take place on 23 January 2017.

Advancement and Agreement

Maintenance and repair crews from Deir Qanun village in Wadi Barada entered Ein al-Fija to repair the damage caused to the water plant. One of the maintenance crews was fired on by the Hezbollah militia group, which then pledged to stop targeting them, allowing the whole group to enter on 13 January 2017.

Damascus’ neighborhoods are suffering from a severe water crisis since the main water pipes were cut off towards the end of December 2016 amid fighting in Wadi Barada that damaged the Ein al-Fija water treatment plant.

The maintenance crews entered after Russian delegations had been trying to enter the area throughout the past few weeks but prevented from doing so on two occasions by Hezbollah fighters at the Deir Qanun checkpoint. They eventually allowed them to enter in order to monitor the situation and implementation of the ceasefire, and negotiate access for the maintenance crew, which they managed to do by contacting local notables from Wadi Barada living in Damascus.

Following more than three weeks of consistent bombardment of the villages and towns of Wadi Barada, the spring suffered damage, which is expected to take several days to repair.

As the maintenance crews were arriving, the al-Assad forces and allied militias were advancing under the leadership of the Lebanese Hezbollah. According to Enab Baladi’s sources, they managed to take control of around 80% of the village of Baseema, which has witnessed what were described as “violent” confrontations in recent days. This was despite a new truce being reached between representatives for the residents of Wadi Barada in northwest Damascus and regime representatives, which applies to all the villages and towns of the area, starting at noon on 13 January 2017.

The advance on Baseema followed the regime forces’ arrival at al-Jisr village without entering the village, according to local lawyer Fouad Abu Hattab. Abu Hattab said that extensive battles took place at the al-Hannawi building during which the al-Assad forces succeeded in advancing only 100 meters. The situation remained unchanged until agreement was reached granting the maintenance crew access to Ein al-Fija at 5pm on 13 January, at which point Hezbollah took the opportunity to finish off its attack and enter al-Jisr village, advancing deeper into Wadi Barada.

On Saturday 14 January (the 24th day of the campaign on Wadi Barada), violent clashes occurred in the village of Baseema during which Hezbollah and al-Assad’s forces tried to advance towards the village of Ein al-Khadhra. Clashes also took place in the Kafr al-Zeit (Ein al-Louz) area with the aim of advancing deeper into the villages of Wadi Barada but no progress was made on this front.

Meetings are taking place in Moscow to discuss the situation in Wadi Barada since water is a vital issue, an issue that may undermine the ceasefire. The continuation of the current situation may undermine the Astana talks.

The United Nations Special Envoy to Syria, Staffan de Mistura, said on 12 January 2017:

“We call on the United Nations to support efforts to investigate events in Wadi Barada… The regime is executing a barbaric campaign based on the principle of “starve or kneel” against over 100,000 residents of Wadi Barada.”

The General Coordinator for the Higher Negotiations Committee, Riyad Hijab, said on 12 January 2017:

“The arrival of the army at Ein al-Khadhra will speed up national reconciliation and the fighters who do not want to settle will leave for Idlib… The area of Wadi Barada will witness settlements similar to those that happened in al-Tell and Qadsaya.”

The Governor of Damascus’ Countryside, Alaa Ibrahim, said on 13 January 2017

Possible Scenarios

The possible scenarios for the valley’s future are completely shrouded in uncertainty. Abu Hattab, who is well-informed about the progress of negotiations between the two sides, told Enab Baladi about one scenario – that the area would become a military zone under the administration of retired Major General Ahmad Ghodhban, a high-ranking retired officer who lives in Ein al-Fija. He is expected to be appointed by the two sides to oversee the agreement and ensure the truce will hold in the long term.

However, while this feature was being prepared, Ahmad Ghodhban was killed by two bullets in the back at the Deir Qanun checkpoint.

Community institutions in Wadi Barada mourned the killing of the Major General, accusing the checkpoint officials of assassinating him. They released this statement, “(The Major General) approached the checkpoint to negotiate and protest the continued military escalation despite the start of the agreement. They shot him twice in the back under the directions of Brigadier General Qais Farwa and the terrorist Hezbollah militia to destroy any hope of a peaceful solution to stem the flow of blood.”

The statement confirmed, “The martyr was heading the negotiating delegation representing the people of Wadi Barada and he was recently assigned to oversee the area’s military and security conditions, according to the peace agreement presented by Major General Ali Mamluk.”

The institutions demanded the faction leaders meeting in Ankara not to go to the Astana Conference and announce the collapse of the political process due to “the fact that it is impossible that the regime and its supporters will respect the ceasefire agreement.”

The community institutions also called on Turkey to fulfill its responsibility as a guarantor of the ceasefire agreement, supported by United Nations Security Council decision number 2336. They demanded that Turkey push for UN observers enter Wadi Barada to monitor the ceasefire and ensure the withdrawal of the al-Assad forces and Hezbollah militia from all areas that they took over after the agreement was signed.

In light of these developments, the continuation of the new agreement requires swift action by the sponsor states. The agreement guarantees that the residents and fighters in Wadi Barada will not be displaced and allows the return of residents of Baseema, Ein al-Fija, Afra and Harira to their villages.

However, pro-regime social media pages, especially those publishing news from al-Fu’ah, stated that the agreement in Wadi Barada is tied to the Shiite town of al-Fu’ah, prompting activists to question the guarantees provided by the regime and its militias, “As perhaps the valley will witness hostage and arrest operations similar to those inflicted on the people of Aleppo.”

There was also talk of the “green buses” being prepared to transport fighters from Wadi Barada to Idlib’s countryside. Well-informed sources told Enab Baladi, “Every person from Wadi Barada must either accept the reconciliation or leave the area” under the agreement. Alaa Ibrahim, the Governor of Damascus’ Countryside Province, seemed to confirm this, stating that he will, “continue to settle the situation of fighters in all areas of Wadi Barada.”

Sources said that dissident army officers and those refusing military conscription in Wadi Barada “will accept the reconciliation and complete their mandatory military service at security distribution points to protect the Ein al-Fija spring,” while “the residents remaining in Wadi Barada will accept the reconciliation.” At the same time, the regime continues to try to advance deeper into the area, shelling it with mortar rockets in breach of the agreement despite the entry of the maintenance crew into the area.

Abu Mohammad al-Bardawi, a member of the Media Commission in the area, previously told Enab Baladi that the regime has repeatedly sent notables from the area demanding a complete reconciliation similar to those agreed in Qadsaya and al-Tell, but opposition factions and the area’s residents rejected the proposal outright.

With Hezbollah and the regime continuing to launch attacks on Wadi Barada’s fronts, it is difficult to predict what events will unfold in the coming days. Will the “rebels” of Wadi Barada fulfill their promise to refuse any agreement that dictates their displacement or will the regime’s repeated attempts to incorporate the area into its areas of “coerced reconciliation” in Damascus’ outskirts succeed?

500,000 years

Historical research viewed by Enab Baladi concurs that the first evidence of human life in Wadi Barada dates back to 500,000 years ago. The area’s civilization flourished in the second millenium B.C., and especially in the Aramaic period.

In Mahmoud Mohammad Alqam’s book, “Wadi Barada Through the Ages,” the Syrian researcher born and brought up in the area presents detailed information, both ancient and recent, about the area’s history to those “eager” to find out and read about its history. He clarified that he refuses to view Wadi Barada’s history separately from that of Damascus or al-Zabadani due to the geographical, social, civilizational and historical ties between them.

In the 144-page book, he explores the history of Wadi Barada throughout the ages from the Aramaic, Greek, Roman, Byzantine and Islamic periods, through to the period of Ottoman rule, the French mandate period and the contemporary period. The book presents historical facts about the changing political and economic situation of the area.

In his discussion of the valley he writes, “Wadi Barada comprises the Barada River, encircling it as it encircles Damascus and providing it with pure spring water. It gives the city its best produce – apples, pears, pomegranates, quince, green plums, apricots, figs, grapes and olives… From this valley, Damascus drank pure water for the first time. Its water lit the first electrical lamps in Damascus’ houses, and it brought silk to the looms of Damascus, in which mulberry cultivation boomed.”

The book includes an article by the historian, Dr. Suhail Zakkar, in which he states, “Life in Wadi Barada goes back further than 500,000 years. Damascus flourished as a city at the end of the second millennium B.C. in the Aramaic period. Wadi Barada was part of the Damascene Aramaic kingdom and the valley is mentioned in many historical books as it was part of the caravan route between the two great cities of Damascus and Baalbek.”

“The History of Damascus” by the historian Ibn Asakir includes information about “Souq Wadi Barada”, indicating that it lies on the banks of the Barada River and is located 30 kilometers from Damascus. Its long-lasting importance stems from its location on the trade routes connecting Damascus to the coast.

Souq Wadi Barada flourished during the Roman period and was known as “Ebalineh”. It was part of Baalbek during the Seljuk period. The village was known as “Ebela” and became the capital and a kingdom that included the area north west of Damascus. Many Latin and Greek texts were found in the area, which list its ruler’s name as “Lisanius” and mention the temple “Zeus Chronos.” The temple later became a shrine for the prophet Cain, although all that remains of it are a few stairs and some etchings in ancient Greek.

The Damascene researcher, Oqba Nidham, wrote about the history of Ein al-Fija in his blog, clarifying that “Fija” is an ancient Greek word meaning “spring”. The town was named thus since “Fij” or “Fija” means lowland surrounded by mountains, reflecting the area’s topography. The area also includes some archeological sites indicating it has been inhabited for thousands of years.

The town includes an ancient Roman temple close to the spring source. The temple used to be called “Hisn Azta” (Azta’s Ramparts) and some parts of this fortification are still found in the northern part of the spring where the sacred stone used by the Romans to present sacrifices to the god of the spring used to stand. The stone is now in the National Museum in Damascus. Ein al-Fija also contains the remains of an old tunnel through which Zenobia, the queen of Palmyra, supposedly drew water from the Barada River to Palmyra city via the plains.

if you think the article contain wrong information or you have additional details Send Correction

النسخة العربية من المقال

-

Follow us :

A

A

A

A

A

A

More In-Depth

More In-Depth