Enab Baladi – Hani Karazi

A French court has issued a new arrest warrant against the ousted Syrian regime leader, Bashar al-Assad, on charges of complicity in committing war crimes in Syria, creating a glimmer of hope among Syrians for holding al-Assad accountable, who fled to Russia amid speculation about the potential for Moscow to hand over the ousted regime leader to international courts.

Two French judges issued the arrest warrant against Bashar al-Assad on January 21 of this month, concerning an attack by the former regime that took place in Daraa in 2017, which killed a civilian named Salah Abu Nabout (59), who held both French and Syrian citizenship.

The warrant was issued after investigations confirmed that Abu Nabout, who worked as a French language teacher, was killed in an attack by helicopters belonging to the former regime, which targeted his home in Daraa.

The French judiciary believes that Bashar al-Assad ordered this attack and provided the means necessary for its execution.

The first step in the path to accountability

Syrians demand the necessity of prosecuting Bashar al-Assad after he fled to Russia; they are not merely satisfied with changing the regime and closing the political chapter of the former president, but they aspire for more, namely achieving justice before international courts.

The French arrest warrant against Bashar al-Assad is set to be reviewed by the Court of Cassation in response to an appeal from the Paris Public Prosecutor’s Office on March 26.

International criminal law attorney al-Mutassim al-Kilani believes that the French arrest warrant is part of a long road to establishing a policy to prevent impunity in Syria, and one of the methods of transitional justice in holding war criminals and perpetrators of crimes against humanity accountable in Syria as part of transitional justice tools.

Al-Kilani told Enab Baladi that the significance of this warrant lies in the fall of presidential immunity for al-Assad, as investigative judges do not consider that the official acts of the ousted president allowed him to commit those international crimes. Additionally, this warrant is the first of its kind concerning the bombing of civilian facilities and the use of barrel bombs.

Russia wants something in return

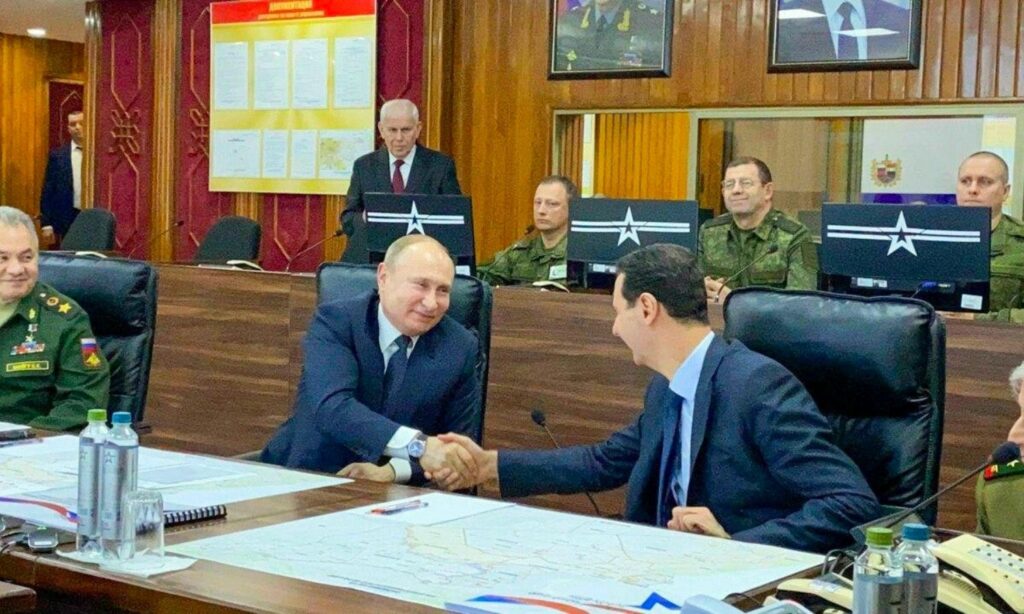

On December 9, 2024, the Kremlin stated that Russian President Vladimir Putin had decided to grant humanitarian asylum to Bashar al-Assad and his family following their escape from Syria after the regime’s collapse.

Regarding the possibility of Russia handing over al-Assad, Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov stated that “Russia is not a party to the Rome Statute that established the International Criminal Court,” indicating its unwillingness to hand over al-Assad.

Al-Kilani believes that there is a legal path for the French judiciary to request Interpol to communicate with Moscow to hand over Bashar al-Assad to French authorities, noting that Russia is obliged to comply since it signed the international Interpol agreement in 1990. He pointed out that there will be international pressure on Russia to deliver al-Assad, and if it does not comply, there will be punitive measures from Interpol against Russia.

He emphasized that the asylum granted by Russia to al-Assad does not protect him from accountability, as the Geneva Conventions regarding refugees do not grant any advantages to those involved in war crimes in terms of humanitarian or political asylum or protection from prosecution.

For his part, political analyst specializing in Russian affairs Mahmoud al-Hamza discounted the possibility of Russia handing over Bashar al-Assad, as it would affect its sovereignty and prestige, and would be an embarrassing matter for Putin, who frequently states that Russia does not abandon its allies. Therefore, they granted him humanitarian asylum to show public opinion that they are humane.

Al-Hamza added to Enab Baladi that al-Assad acts as a pressure card in Russia’s hand; if it decides to hand him over for trial, it would do so in exchange for an agreement with the new Syrian administration. Moscow might demand a price for handing over al-Assad, such as maintaining its military bases in Syria and continuing economic, commercial, and military relations between Moscow and Damascus, which serves Russian interests in the long term.

Two paths to the International Criminal Court

Over the past few years, the Security Council has repeatedly attempted to refer the Syrian file to the International Criminal Court but failed due to the Russian-Chinese veto. This pushed some countries and human rights organizations to seek to hold the regime accountable through European courts, which are allowed by virtue of universal jurisdiction to prosecute criminals outside their territories who have committed violations against their citizens living in Syria.

In November 2023, the French judiciary issued an arrest warrant against the Syrian regime leader, his brother Maher, and two senior aides, on charges of carrying out chemical weapons attacks in Eastern Ghouta in 2013.

Al-Kilani stated that under international law, it was not possible to issue an arrest warrant against a head of state in office or to prosecute him in absentia, as this would violate international agreements related to diplomatic immunity for heads of state still in office. However, after al-Assad’s fall, his immunity was lifted, and the legal path to accountability became accessible.

Al-Kilani noted that there are two paths to referring the file for prosecuting al-Assad to the International Criminal Court: the first is that Syria signs the Rome Statute, which would allow it to give the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court authority to investigate serious violations committed by al-Assad, and the second path is for the Security Council to refer the Syrian file for a vote to refer Bashar al-Assad to the International Criminal Court.

He added that if the file of prosecuting al-Assad is transferred to the International Criminal Court, the court can request through the states signatory to the Rome Statute (124 countries), if citizens of one of those states have a complaint against al-Assad. Consequently, one of those states, such as France, could distribute the warrant to the countries that signed the international Interpol agreement (196 countries), including Russia, to hand over al-Assad.

On May 22, 2014, there was a session in the Security Council to refer the Syrian file to the International Criminal Court in order to hold the Syrian regime accountable for its crimes, but the Russian-Chinese veto obstructed that referral.

A total of 108 countries signed the Rome Statute for the International Criminal Court in 1998, and many countries, including Syria and Iraq, have not signed the treaty, and thus, the court does not intervene in cases on Syrian territory. However, the court can automatically exercise judicial authority over crimes committed on the territory of any member state or committed by persons belonging to any member state.

In this context, Mahmoud al-Hamza emphasized that Russia handing over Bashar al-Assad to the International Criminal Court is out of the question, as Putin himself is wanted by the same court, and thus handing over al-Assad would put Putin in an embarrassing position. He pointed out that if Russia faced significant international pressure, it might force al-Assad to leave its territory and travel to another destination, such as the UAE, for instance.

Second arrest warrant

The French arrest warrant issued against Bashar al-Assad last week is considered the second of its kind.

French investigating judges issued an arrest warrant against al-Assad, his brother Maher, and two of his aides, charging them with using chemical weapons in Eastern Ghouta in August 2013. This followed a criminal investigation conducted by the specialized unit for crimes against humanity and war crimes in the Paris judiciary.

However, the French national anti-terrorism public prosecutor’s office requested that the appeals court rule on the validity of the warrant, as al-Assad was then a head of state enjoying immunity, which led to objections from human rights organizations and international bodies demanding non-recognition of his immunity.

The second arrest warrant came after al-Assad’s fall and was issued following a long process initiated by Omar Abu Nabout, a 28-year-old son of Salah Abu Nabout, a Syrian citizen holding French nationality, who was killed by the aircraft of the previous Syrian regime in the city of Daraa.

Omar began gathering evidence and preparing a case file after his father’s death, filing a complaint with the Paris court in 2017. The public prosecutor approved the complaint, which was forwarded to the war crimes and crimes against humanity unit in the French court, as Omar Abu Nabout told Enab Baladi.

The war crimes unit in the court opened an investigation based on the complaint regarding his father’s murder, appointing two judges to investigate and accepting the victim’s son, Omar, as a civil party.

Omar worked on reaching out to witnesses and played the role of both lawyer and plaintiff for three years. He appointed a lawyer to follow up on the case with him, but the lawyer proved untrustworthy and failed to attend the first session with the judge at the beginning of 2018. Omar attended with only a translator due to his limited proficiency in French, as he had recently arrived in the country.

The Syrian Center for Media and Freedom of Expression joined the complaint as a local expert on the case, later being appointed by Omar as a civil party in 2020 with his willingness and approval to provide as much evidence as possible to the judges and expedite the justice process he aspired to achieve.

The Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR) also contributed to supporting the investigation by providing detailed information to the judges and presenting witnesses about the incident of barrel bomb attacks on Daraa on June 7, 2017, which led to the death of Salah Abu Nabout.

After six years of efforts and evidence gathering, Omar made progress towards justice for his father, and on October 18, 2023, the French judiciary issued arrest warrants against four Syrian officers: Fahd Jassim al-Freij, Ali Abdullah Ayoub, Ahmed Baloul, and Ali al-Saftli.

On January 21 of the current year, the French judiciary issued a new arrest warrant against Bashar al-Assad in connection with the case of the murdered French-Syrian citizen Salah Abu Nabout.