Landmines and unexploded remnants of war pose one of the most severe threats facing Syrians in the post-regime collapse era, hindering the return to normalcy and the resumption of work.

Between November 27, 2024, and January 10 of the current year, the Syria Civil Defence documented the deaths of 35 civilians, including 8 children and one woman, and the injuries of 54 civilians, including 23 children, due to explosions from war remnants and landmines in various regions of Syria.

According to a report from the The Halo Trust organization on January 9, approximately 80 civilians, including 12 children, were killed by landmines and other remnants of war in the month following the regime’s collapse on December 8, 2024.

The Civil Defence describes the remnants of war resulting from the previous regime’s bombardment as a long-term, ongoing danger affecting civilians’ lives, as they remain explosive for years and impact residential areas, agricultural lands, and children’s play areas.

Despite the efforts made in demining operations, they are “extremely limited” and are likely to continue for a long time, with the danger stemming from this war legacy still present.

Maysarah al-Hassan, the engineering team leader in northern Syria and the Badia region, told Enab Baladi that the number of landmines is estimated in the millions.

He added that there are over 200 mined villages in northern Syria, in addition to over 260 documented minefields marked with warning signs to prevent approach and maps indicating the distribution of the mines.

The teams identified about 65 minefields in the region between Minnigh and Mar’anaz in the rural area of Aleppo, with each field containing between 2,500 and 3,000 mines, according to al-Hassan.

He referred to the method of accessing the areas where the mines are located, stating that they work on gathering as much information as possible by reaching out to former officers who worked with the ousted Assad regime, asking them about the locations where mines were planted and mapping them to determine sites for dismantling and removal.

A report from The Halo Trust quoted the organization’s operations coordinator in Syria, Mouiad al-Nofaly, stating that this “deadly legacy” will continue to kill and maim future generations unless serious efforts are made to address it.

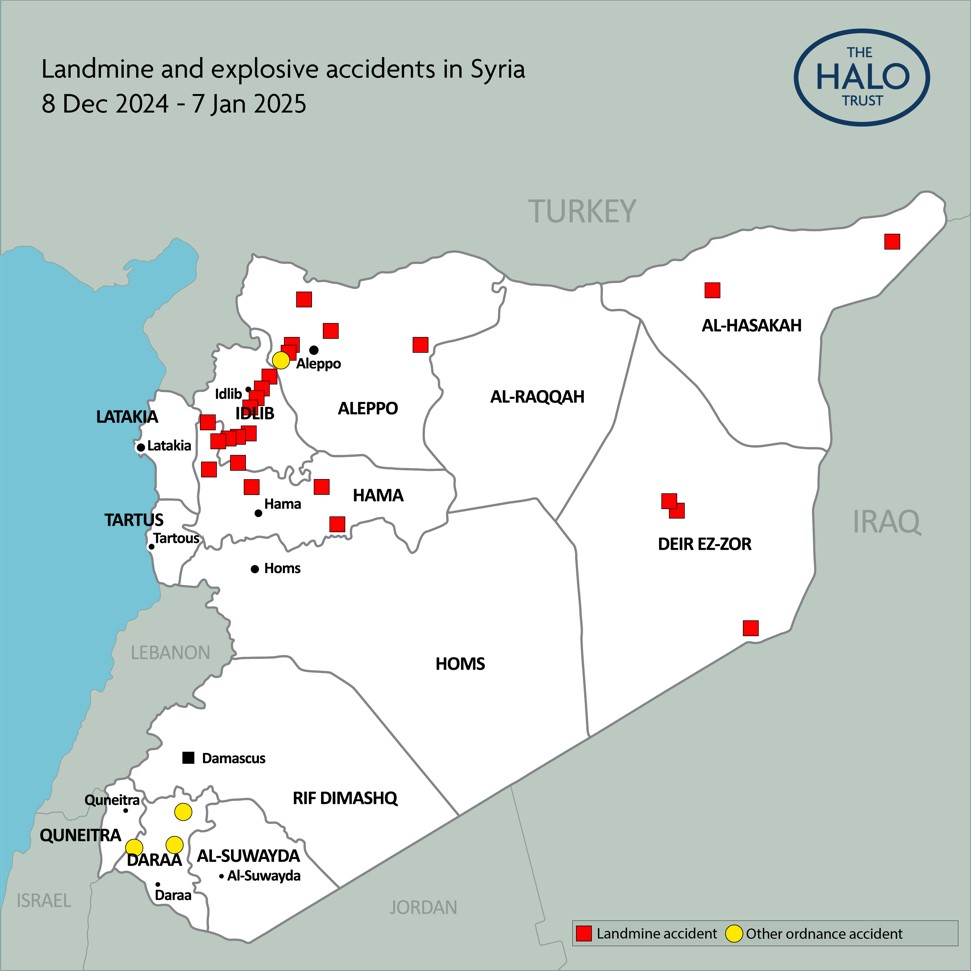

The organization has documented the locations of incidents resulting from landmine explosions in many Syrian regions through maps to determine the spread of these remnants.

Between November 27, 2024, and January 3 of the current year, Syria Civil Defence teams identified 117 minefields and points containing mines in the provinces of Aleppo, Idlib, Hama, Latakia, and Deir Ezzor.

The Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR) has also documented the locations of landmine and cluster munition explosions and created approximate maps of landmine-contaminated areas in Syria. They added that these maps help identify danger zones and facilitate demining efforts while raising awareness among residents and authorities to protect lives.

Map showing locations of incidents resulting from landmine explosions between December 8, 2024, and January 7 of the current year (The Halo Trust)

Demining teams in Syria face challenges in detection and removal operations due to a shortage of the necessary personnel and equipment to carry out their tasks safely and efficiently.

According to Maysarah al-Hassan, the engineering team leader in northern Syria and the Badia, the teams currently rely on rudimentary and simple equipment, including protective vests, ordinary helmets, and basic metal detectors.

He clarified that “de-mining operations require advanced equipment such as armored vehicles, specialized shields, and modern devices for detecting mines, in addition to significant international support to provide these needs.”

He added that about 30 engineering teams are working in northwestern Syria, specifically in Minnigh, Tal Rifaat, al-Malikiyah, Mar’anaz, and the villages extending to al-Bab in northern Aleppo.

Al-Hassan confirmed that efforts are being made within the currently available resources, with attempts to communicate with the General Command in Damascus to develop a comprehensive action plan to supply the teams with the necessary equipment and machinery.

The teams also seek coordination with international organizations specializing in demining to receive necessary support.

Al-Hassan pointed out that there is an urgent need to provide advanced machines such as mine-sweepers and detectors, which are currently unavailable.

The teams are working without health insurance or sufficient medical support, which increases the danger of these tasks, according to al-Hassan.

He added that “greater coordination and cooperation with specialized teams will be crucial factors in ensuring the complete removal of mines from all Syrian regions.”

In some areas of Syria, such as Deir Ezzor, Raqqa, and Homs, civilians are removing mines manually without any precautions, and scenes shared by activists show civilians, including shepherds, casually removing mines without any prior experience in an area near Palmyra in eastern Homs.

Mouiad al-Nofaly, operations coordinator for The Halo Trust in Syria, stated that the organization estimates the cost of demining and disposing of unexploded ordnance at approximately 40 million US dollars annually, adding that these operations could save thousands of lives.

The types and sources of mines vary according to regions and different phases of the war.

Al-Hassan explained that the main types of mines discovered during removal operations include anti-personnel and anti-vehicle mines.

He noted that most of them are of Iranian and Russian manufacture, in addition to locally made munitions such as improvised explosive devices that were planted by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) during their withdrawal from northern villages.

He added that landmines not only threaten lives but also hinder the return of residents to their areas and prevent them from resuming their normal lives, especially in agricultural regions that many families rely on for their livelihoods.

Regarding the areas focused on, al-Hassan stated that priority is given to public roads, village entrances, and pastures in the Badia, as well as warehouses and stores for prompt removal, followed by fields and agricultural lands surrounding villages.

Maysarah al-Hassan, the engineering team leader in northern Syria and the Badia, regarding the plan for mine removal, said they are awaiting decisions from the Military Operations Administration to work on the mine file, adding that they are currently working within the available capabilities.

He indicated that it may take a year or two to achieve complete removal and clearing, in order to ensure the safe return of the people to their areas.

He expressed hope for cooperation with international teams and specialized organizations to provide them with the required tools and personnel in the future.

Despite their scarcity, organizations are working more on awareness, according to al-Hassan.

According to the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), removing unexploded ordnance can take many years.

Until that is achieved, other measures must be taken to reduce the danger of these remnants to civilians and decrease the likelihood of casualties or injuries.

Possible precautions, such as marking areas with explosives in contaminated areas and fencing and monitoring those areas, in addition to issuing warnings and raising awareness among residents of the risks, can help people live safely despite the presence of these remnants.

The Civil Defence reported that its teams conducted 177 practical training sessions for residents before their return to the areas they had displaced from, in addition to ongoing awareness campaigns shared by the Civil Defence on social media platforms to raise awareness of dangerous war remnants.

In its awareness campaign, the Syria Civil Defence calls to follow the “golden rule of protection”: “Do not approach, do not touch, report immediately,” emphasizing the necessity to avoid any suspicious objects that could be mines for protection against this danger.

For its part, the Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR) is participating in awareness campaigns through guidelines that include avoiding areas contaminated with mines, not touching suspicious objects, and reporting them.

The Halo Trust has also designated a hotline for reporting the presence of mines or remnants of war to assist in dismantling and removing them.

The Halo Trust states that there is a “critical” need for international efforts to remove millions of cluster munitions, landmines, and unexploded ordnance to save the lives of hundreds of thousands of returning Syrians and pave the way for sustainable peace.

if you think the article contain wrong information or you have additional details Send Correction