Khaled al-Jeratli | Yamen Moghrabi | Ali Darwish

After 2011, Syrians saw the first military tank moving contrary to the path they had always expected, heading towards the Syrian interior instead of the southern borders occupied by Israel. The motivation for this movement was to suppress the anti-regime movement in Daraa, Syria, which is close to the occupied Golan, after the Syrian regime failed to calm the situation with threats and intimidation.

More than 50 years have passed since Israel took control of the Golan in 1967. Syrians have always viewed the Golan as occupied land that should be liberated, and some go even further, demanding the liberation of all of Palestine.

Today, after 13 years of the Syrian army’s involvement in suppressing the revolution across the Syrian geography, a missile believed to be from Hezbollah, a regime ally in suppressing the Syrian uprising movement, towards the occupied Syrian Golan, resulting in the death of 12 civilians, has awakened a lot of debate and questions. Were the civilian victims Syrians or Israelis in terms of nationality? All that has been known about the Golan over the past decades is that it is Syrian land. Some of its residents were displaced to the Syrian interior, and others remained in the occupied territories.

In this file, Enab Baladi discusses with experts and researchers the social composition in the occupied Golan and the transformation of the geographical area into an ever-lasting negotiation file, where the Syrian regime seeks gains at both the regional and local levels.

Syrian land devoured by settlements

The occupied Golan is similar to other lands that Israel occupied in the 1948 Nakba and the 1967 Naksa. Most of its residents were displaced, and the occupying forces took control of their properties, building settlements on the ruins of their villages and farms, housing Israeli settlers, and besieging the remaining Syrians in their villages and constraining them politically, economically, and socially.

The Golan was of political and economic importance to Israel before its occupation in 1967. After its occupation, its significance doubled. The Knesset decided to annex it to the Israeli administration in December 1981.

Residents of the Golan bid farewell to 12 people, including children, killed by shelling that Israel said originated from the Lebanese Hezbollah – July 28, 2024 (Reuters)

Geography of the Golan

The Golan is located in the far southwest of Syria along the border with Palestine. It has an elongated shape, extending from north to south for 75 kilometers and a width ranging between 18 and 27 kilometers, with an area estimated at 1860 square kilometers.

It is characterized by its varying elevation above sea level. In the north, its hills neighbor Mount Hermon, rising over 2000 meters; then it decreases to 1200 meters in the village of Majdal Shams and reaches about 125 meters in the south.

The Golan is one of the richest areas in Syria in terms of groundwater, representing 14% of Syria’s water reserves before 1967, according to the Syrian Ministry of Foreign Affairs website.

The area occupied by Israel in 1967 is estimated at 1250 square kilometers. Only 100 square kilometers were reclaimed during the October War in 1973, meaning the currently occupied area is 1150 square kilometers.

According to a 1966 census, the Golan had a population of 153,000, with 138,000 in the area occupied by Israel. Of these, 131,000 were displaced after the 1967 war, and 7,000 remained. The current estimated number of displaced Golan residents is 600,000.

Administratively, there were two main cities, Quneitra and Fiq, along with 164 villages and 146 farms. Currently, there are 137 villages under occupation and 112 farms.

The residents of five villages remained under occupation: Majdal Shams (the largest), Buka’ata, Ein Qinya, Ghajar, and Su’heita, in addition to Masada, which was a farm at the time. Israel built 45 settlements in the same area.

The writer specializing in the occupied Golan affairs, Muhammad Zaal al-Salloum, told Enab Baladi that Masada was a farm linked to Majdal Shams, but after the displacement of Su’heita residents, it expanded and became a village.

Syrian enclave in the north

The Golan inhabitants are concentrated in the northern regions, close to Mount Hermon, while Israeli settlements are concentrated in the southern parts. However, Israel continues to pressure the original inhabitants by building settlements and military points near or around the four villages where residents have preserved their lands.

They are also pressured through economic projects, the latest being the wind turbine project, set on an area of 3674 dunams on private land in the Syrian villages of Majdal Shams, Masada, and Buka’ata, about one and a half kilometers from Ein Qinya.

Writer Muhammad al-Salloum, a displaced Golan native and author, said to Enab Baladi that Majdal Shams, Masada, Buka’ata, and Ein Qinya are inhabited by Druze Syrians, while Ghajar’s residents belong to the Shiite sect, many of whom have acquired Israeli citizenship and serve in the Israeli army and police, unlike other village residents who have repeatedly refused Israeli citizenship since it was offered to them in the 1980s.

Al-Salloum added that the Golan was inhabited by Sunni Arabs, Circassians, Turkmens, and Alawites, but none remained after the occupation.

Currently, the Druze in the four villages number around 20,000, with 12,000 in Majdal Shams and the rest distributed among the other three villages. About 50,000 Jewish settlers live in the Golan, according to the Israeli Bureau of Statistics cited by The Times of Israel.

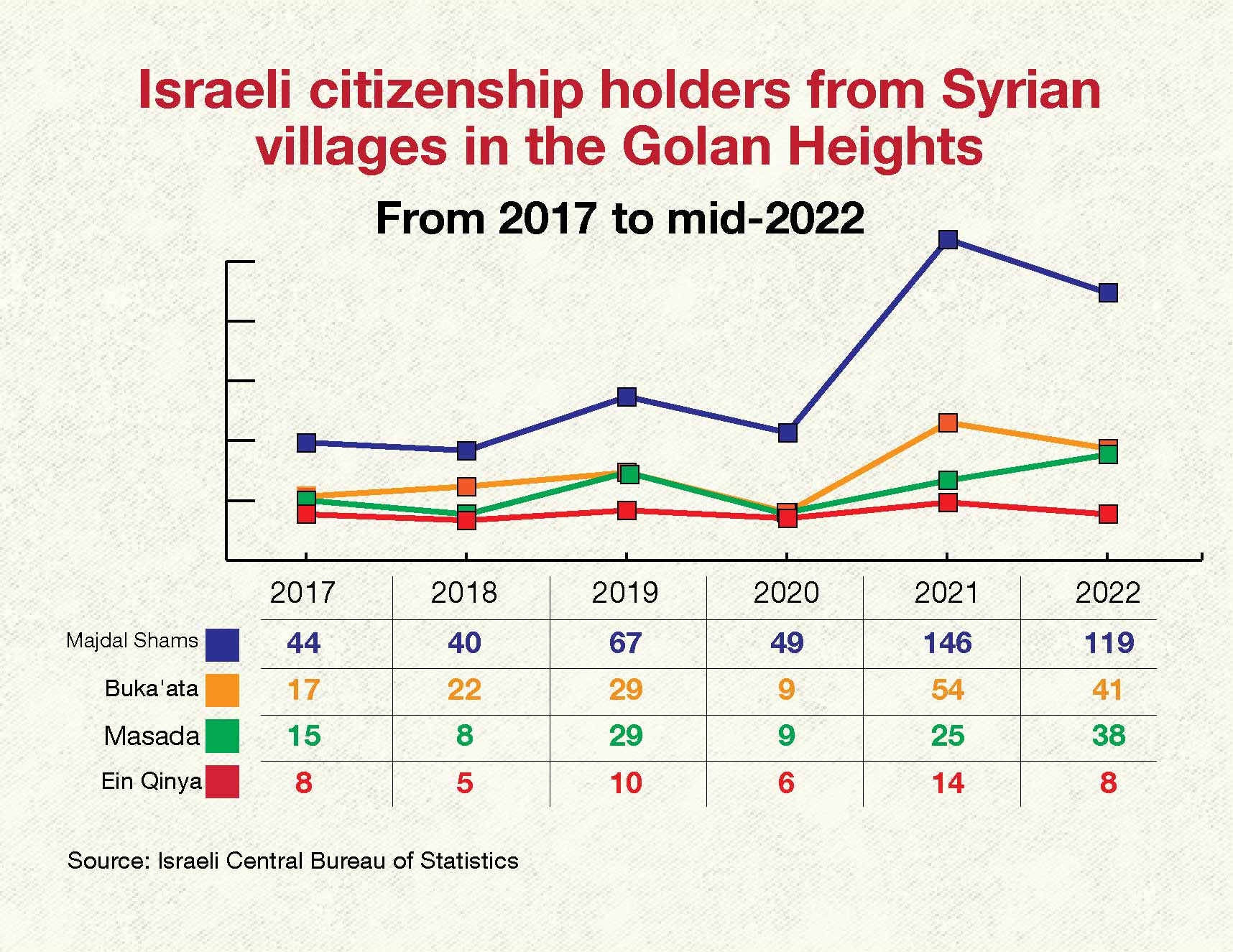

About 25% of the residents in the four villages have obtained Israeli citizenship. However, in the 2022 Knesset elections, only 169 people from Majdal Shams out of 962 eligible voters participated in the elections. The village has 2068 people with Israeli citizenship.

As of mid-2022, the number of people with Israeli citizenship in the four villages totaled 4303, but Israeli reports indicate an increasing tendency among the villages’ residents to apply for Israeli citizenship.

Syrians refusing Israeli citizenship carry “temporary residency” cards, retaining their Syrian nationality. They are faced with two options: remain as they are or be forced to take Israeli citizenship, meaning their children would serve in the Israeli army.

Golan residents also face difficulties obtaining scholarships at Western universities.

The Golan Druze have battled Israel on multiple fronts. Politically, they refused to acquire Israeli citizenship to maintain their identity. On the social and economic front, they resisted Israeli policies that deprived them of water resources, lacked regional development and infrastructure, and exploited the Golan’s environment for economic projects such as the wind turbines.

Economy and politics

“Israel turns the Golan into an open environmental park for tourists and settlers,” says writer Muhammad al-Salloum. However, he adds, Israel has also destroyed part of its fundamental ecosystems and introduced new elements. Before the Al-Aqsa Flood operation in October 2023, Israel was investing around three billion dollars in the Golan.

For Israel, the Golan’s most critical issue is water. Before the Golan’s occupation, Israel was executing projects to divert the Jordan River’s water from its sources and feeding streams in Syrian territory before occupation. These include Mount Hermon slopes and the Dan and Banias springs, flowing into Lake Tiberias and continuing the Jordan River’s flow southward.

Al-Salloum stated that during the 1950s, the Golan provided 80% of Damascus’s livestock, milk, and dairy needs and 50% of Hawran’s needs.

Currently, Israel exploits these waters entirely, creating many water tanks and reservoirs such as Bab Al-Hawa, diverting the waters to occupied territories servicing settlements.

In the tourism sector, Israel benefits from the diverse landscapes of the Golan, from mountains, hills, and plains to waterfalls. It also takes advantage of areas with significant religious importance to Christians in the occupied region, such as Bethsaida, Banias’s Nimrod Fortress, Kursi’s Church Ruins, and the Banias Temple, which Jesus visited frequently, where he handed Peter the church’s keys, according to Christian narratives.

The Golan also holds military and security value, according to writer al-Salloum. The Golan is only 65 kilometers from Damascus, serving as an advanced post for Israel, allowing control over its hills and heights and acting as a natural barrier between historical Palestine and Syria.

American view: The Golan is Israeli

On July 29th, the US State Department stated that the occupied Syrian Golan Heights are crucial for Israel’s security as long as the Syrian regime governs Syria and Iranian militias continue to spread across Syrian geography.

During a press briefing, Vedant Patel, Deputy Principal Spokesperson of the State Department, said that the Golan is extremely important and vital for Israel’s security as long as the Assad regime remains in power in Syria and Iran and its proxies continue to exist in Syria.

Patel, during his response to journalists’ questions, considered that as long as the Syrian regime poses a “significant security threat” to Israel, control over the Golan in practical terms remains of real importance to Tel Aviv.

He pointed out that US policy regarding the Syrian Golan Heights has not changed since former President Donald Trump declared recognition of the Golan as Israeli territory, which did not receive an international response.

The US State Department’s statement coincided with a press conference in which White House National Security Advisor John Kirby said that Washington continues to recognize Israel’s sovereignty over the Golan Heights.

He added that the US declaration in 2019 has not changed and quoted, “The aggressive actions by Iran and terrorist groups, including Hezbollah, in southern Syria continue to make the Golan Heights a potential launching point for attacks on Israel.”

Half-century of negotiations

On June 5, 1967, a war broke out between Syria and Egypt on one side, and Israel on the other, where Israel attacked Syrian and Egyptian airports, entered the West Bank, Jerusalem in Palestine, and the Syrian Golan, as well as Egyptian Sinai, amidst the inability of the Arab military forces. Within approximately a week, Israel declared its victory.

The fall of the Golan constituted a setback for Syria due to its strategic location, which is only 65 kilometers from the capital, Damascus, in addition to Israel’s control over the Mount Hermon Observatory overlooking the capital. The Golan Heights also overlook southern Lebanon, northern occupied Palestine, and a large part of southern Syria.

Despite the 57 years since the Golan’s occupation and 51 years since the October War in 1973, Syria has not succeeded in reclaiming the area necessary for water security and strategic security. In 1974, the two sides signed the Disengagement Agreement.

The agreement, published by the Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestinian Question and the State Archives of Israel, included the positions of forces on the ground and their respective control areas, the return of prisoners of war, wounded soldiers and the bodies of soldiers, and the establishment of a UN monitoring force. The agreement was signed on the Syrian side by Hikmat Shihabi, a close ally of the former Syrian President Hafez al-Assad.

After 1973, the war between Syria and Israel moved out of Syrian territory, specifically the Golan, to Lebanon during Israel’s invasion of Beirut in 1982. However, another track between the two parties emerged, known as the “negotiation track,” which lasted until Hafez al-Assad’s death in 2000 and his son Bashar al-Assad’s ascension to power in Syria.

Negotiation track

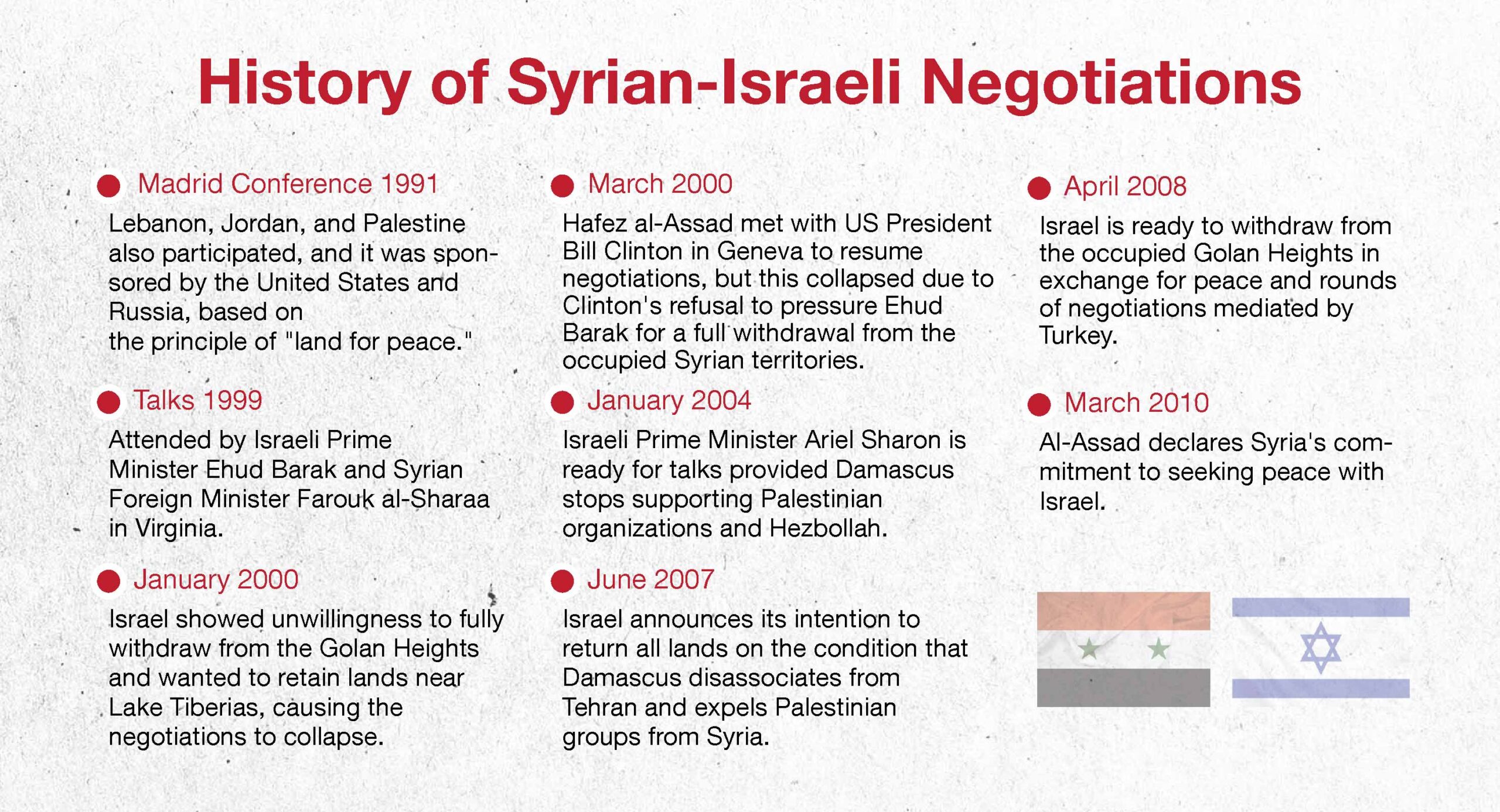

The late 1980s imposed new regional conditions on Syria, as the Lebanon War ended in 1990, the same year Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait, and the final months of the Soviet Union before its collapse the following year. This forced Hafez al-Assad to take a different path than in the 1970s and 1980s, and he moved towards negotiations with Israel at the Madrid Conference in 1991, which became one of two main stations in this field, along with the Camp David negotiations.

According to the book “Syria and Israel: From War to Peacemaking” by Moshe Ma’oz, al-Assad sought since 1988 to prioritize diplomacy over war, and Syria seemed ready to strike a peace deal. Simultaneously, al-Assad’s ties with Iran, Palestinian factions, and Hezbollah increased.

In March of that year, Syrian Foreign Minister Farouk al-Sharaa met with US Secretary of State James Baker and informed him that he had worked with both Egypt and Israel for 14 months to conduct talks between Palestinians and Israelis, urging for a regional conference. According to his memoir “The Missing Account,” al-Sharaa responded with a call for an international conference.

Israel aimed, according to al-Sharaa, for economic cooperation with the Arabs. Baker visited al-Assad in Damascus for a three-hour meeting and returned in April 1991 for a nine-hour session.

Baker continued his rounds between regional countries until October 1991, involved in complex negotiations, leading to the Madrid Conference in October 1991. However, negotiations between Syria and Israel failed, while they led to the Oslo Accords with the Palestinian Authority in 1993, the Wadi Araba Treaty with Jordan in 1994, and halted with al-Assad in 1996, though they also resulted in the Rabin Document, a verbal pledge from former Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin before his 1994 assassination to withdraw from the Golan in exchange for normalization.

Negotiations did not stay absent for long. Washington resumed talks with al-Assad about possible peace, as reported by the Saudi magazine “Al-Majalla” and noted by al-Sharaa in his memoirs. Communication never ceased and meetings resumed in 1999 within the concept of the “four legs of the table,” referencing four elements forming peace between the two parties.

These elements are Israel’s full withdrawal from the Golan, security arrangements, normalization of relations, and a timeline for implementation.

In 1999, al-Sharaa met Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak and US Secretary of State Madeleine Albright in the United States, confirming a “deep desire” for peace.

The meeting followed communications between US President Bill Clinton, Hafez al-Assad, and Ehud Barak, the then-Israeli Prime Minister.

According to al-Sharaa, these official meetings were preceded by secret meetings between experts in isolated locations before announcing the resumption of negotiations. There was only one direct negotiation session amid disputes over historical boundary lines of the “June 4th Line” (the last line Israel controlled before the 1967 war). While Israelis demanded that Syrians stay away from the lake’s borders, Syrians rejected it, and al-Assad also turned down a Canadian proposal to turn all lands around the lake into natural preserves.

Throughout 1999, delegations did not reach a final agreement leading to a peace treaty between Syria and Israel, even with a meeting between al-Assad and former US President Bill Clinton that year.

Six months after the last attempt to form a peace agreement between al-Assad and Israel, Hafez al-Assad’s death was announced in Damascus. His second son, Bashar al-Assad, took the presidency after a constitutional amendment reduced the presidency age limit from 40 years at the time to 34.

Indirect negotiations

After the death of his father, al-Assad junior found himself amidst complicated local and regional circumstances. Information leaked by Arab media in 2004 spoke of the possibility of new peace talks, and that some meetings were held between the parties in Turkey and Europe, mediated by the Syrian-American businessman Ibrahim Suleiman.

Following the July War, Israel announced in 2007 its readiness to conclude a peace agreement with Syria, on the condition that it cuts its ties with Tehran and Hezbollah and expels Palestinian factions from its territory. In the same year, Syrian Foreign Minister Farouk al-Sharaa stated that Syria had no intention of going to war with Israel, but knew that Israel was looking for any pretext to do so. His deputy at the time, Ahmed Arnous, also said that Syria was ready to negotiate based on the Madrid Conference framework (land for peace) without preconditions.

The statements remained without serious action. However, a Turkish intervention in 2008 helped stir the stagnant waters of negotiations between the parties, and indirect meetings were held before they collapsed due to the Israeli war on Gaza.

In 2010, al-Assad announced during a television interview with Hezbollah-affiliated al-Manar channel, Syria’s commitment to seek peace with Israel, considering war as “the worst solution.” Nonetheless, he did not hold out “hope in the Israeli government.” The Israeli newspaper Haaretz stated that peace with Syria should come first to prevent it from sliding into the arms of Iran.

What is the Golan to Syria?

Throughout the years of the al-Assad rule, relations with Israel ranged from war and battles to complex peace negotiations, with neither path restoring Syrian lands. However, both al-Assad (father and son) managed to use this situation to reinforce their rule over Syria by raising nationalist slogans that resonated with the public sentiment concerning reclaiming land and the Palestinian cause.

Negotiations take a long time to achieve due to the complex details involving borders, demarcation, security influence, economic, political, and cultural relations. While it is not necessary for every peace agreement to cover comprehensive details, it usually includes, at the very least, many specific details, especially in cases of wars and conflicts.

Syrian writer Muhammad al-Salloum believes that the political importance of the Golan to Israel lies in it being a negotiating point.

He added that the regime has not reconciled with Israel because it benefits from keeping the Golan “a point to justify and cover the Iranian Shiite project in the region.”

Neither peace nor war

Hafez al-Assad was the Minister of Defense in Syria in 1967 when the Golan fell. Later, former Syrian officials spoke about the ambiguity surrounding the withdrawal of the Syrian forces before the arrival of Israeli forces in the area, through the issuance of announcement “66”. Among them was the former Information Minister at that period, Mohamed al-Zoubi, without any documents confirming the matter.

Al-Zoubi stated in television interviews that the announcement was issued at al-Assad’s request.

Later, al-Assad continued, even after the October War in 1973, to raise nationalist slogans in his speeches and oppose Israel, as did his son Bashar during peace talks. This gives an impression of how both view Israel and the Golan.

According to political analyst Hassan al-Nifi, it can be asserted that the Syrian regime, since 1971, handled the Golan issue through two different perspectives.

The first refers to a kind of “psychological crisis” buried under feelings of guilt and inferiority complex, due to the direct accusations against Hafez al-Assad for his direct responsibility for the loss of the Golan when he was the Minister of Defense. Perhaps this matter is what made him repeat one day: “I want the whole Golan.”

The second perspective considers the occupation of the Golan allowing the regime to maintain a “no war, no peace” state, which the regime has always sought to perpetuate to leverage it against its failure in other obligations, whether internal related to developmental issues or freedoms, or external to extort other Arab countries.

Al-Nifi believes that the Golan or Palestine, or any Arab part occupied by Israel or otherwise, has no intrinsic value for the regime unless it serves the primary interest of the authority. Hence, Hafez al-Assad and his son afterward adhered strictly to the rules of engagement on the Golan front.

A quiet front

Between the military battles that moved from Syria to Lebanon during Hafez al-Assad’s rule, or later when he engaged in complex negotiations, Syria entered practically into a state of neither war nor peace. Over the years, the Golan front became one of the quietest, until the year 2011.

In June of that year, hundreds of protesters tried to storm the border for the first time since 1974. Israel responded by opening fire on them during the anniversary of the 1967 Naksa, and some managed to cross the first line of barbed wire fences. Hundreds of youth in the town of Majdal Shams in the occupied Golan attacked Israeli forces, as reported by the BBC, with similar attempts occurring earlier during the 1948 Nakba anniversary.

It is unknowable if al-Assad issued orders allowing the protesters to move to the area. Yet, this theory may hold some weight considering al-Assad’s complete security control over Syria and the calmness of the front itself.

According to political analyst Hassan al-Nifi, the Golan front did not witness a single bullet from the Syrian side for over 40 years, and the Syrian regime reaped the benefits by ensuring Israel’s keenness not to overthrow him as a regime considering him the ideal guardian of its borders. It is perhaps one of the strange paradoxes that the decision to keep or remove the regime is an Israeli decision to this day, according to al-Nifi’s view.

Al-Assad does not want the Golan to return to Syria as land, but instead desires it to remain a pending matter subject to political deals and investments. This option allows him to benefit from the Golan security-wise and authoritatively.

Hassan al-Nifi, Political analyst

Keeping the Golan occupied spares al-Assad from facing other obligations, granting him a front-row seat within the ranks of the “resistance axis.”

The revolution’s repercussions

The political split that occurred at the beginning of the Syrian revolution in 2011 did not stop at the demilitarized zone. It entered the Golan, and terms familiar to Syrians after the revolution, like “lovers of the regime, thugs, Baathists, informants,” became common, as journalist Hassaan Shams, a Golan native, told Enab Baladi.

He added that the regime’s intervention in the region led some Golan residents to organize pro-regime marches, raising pictures of its president Bashar al-Assad, while some others stood against him and supported the Syrians’ demand for freedom from the regime’s rule.

The Syrian revolution had reverberations among Golan residents themselves, prompting some to seek Israeli citizenship alongside other factors, making it a stark necessity with no alternatives left.

Since Israel occupied the Golan in 1967, 7,000 people were living there. Today, around 27,000 reside, most of whom were born after the occupation.

Journalist Hassaan Shams added to Enab Baladi that the number of people seeking Israeli naturalization was limited when the decision to annex the Golan was issued, following the region’s military rule. It was a tense period concerning the residents’ relationship with the occupation authorities who tried to impose Israeli citizenship by force of arms.

Over the years, the region’s residents maintained their hold on Syrian citizenship. But the violence used by the Syrian regime against Syrians in 2011, and the regime’s transfer of the societal rift in Syria to the occupied Golan, had repercussions on the residents.

According to journalist Hassaan Shams, the Syrian regime’s interference in the Golan’s social structure left a vertical and horizontal division, and the regime never stopped vandalizing the occupied villages’ social fabric since 2011, regardless of the sensitivity and specificity of these villages under occupation.

Regardless of the Syrian regime’s crimes, it had to consider the sensitive geography and view its primary duty as liberating the Golan, given that the regime had been whipping Syrians for decades under the pretext of freeing the Golan and its people, especially with the knowledge that Israel had been trying to detach the Syrian identity from the region’s residents.

Hassaan Shams, Journalist originally from the occupied Golan

While the Golan residents live on their land with documents similar to “permanent residency,” there is not much scope for those wishing to complete their education in universities or travel abroad.

Previously, Golan residents would travel to Syria through UN peacekeepers’ vehicles to complete their education at Syrian universities. After the Syrian revolution erupted, the regime halted this agreement, leaving the residents with one option: spreading across the world in search of academic pursuit. But traveling abroad is not an available option for most, given they do not possess recognized documents.

The journalist told Enab Baladi that Israel revokes the documents of those who remain abroad for four consecutive years and those holding permanent residencies in foreign countries. This prompted many Golan residents to obtain Israeli citizenship as it improved their options for obtaining visas and enabled their return to the Golan later.

Golan residents’ relation with Syria

After half a century of the Golan occupation, new generations emerged who did not witness what their forefathers talked about. Some stuck to the demand for the Golan’s return to Syria, but a significant part of the residents does not know Syria. What remains for them are just the slogans.

Golan residents’ views and relationships with Syria changed after the Syrian revolution according to journalist Hassaan Shams. He told Enab Baladi that some residents hold pro-regime marches for various reasons, including slogans of liberation and Arabism.

On the other hand, there are residents opposing the regime, supporting the demands of the people of As-Suwayda, for instance.

He added that another faction holds no affection for the Syrian regime irrespective of the Syrian revolution, viewing both the regime and Israel as two sides of the same coin. Some believe their existence under occupation is a direct result of the Syrian regime’s rule over Syria and as a guardian of Israel’s security.

if you think the article contain wrong information or you have additional details Send Correction

النسخة العربية من المقال

-

Follow us :

Residents of the Golan bid farewell farewell to 12 people, including children, killed by shelling that Israel said originated from the Lebanese Hezbollah - July 28, 2024 (AFP, modified by Enab Baladi)

Residents of the Golan bid farewell farewell to 12 people, including children, killed by shelling that Israel said originated from the Lebanese Hezbollah - July 28, 2024 (AFP, modified by Enab Baladi)

A

A

A

A

A

A

More In-Depth

More In-Depth