Khaled al-Jeratli – Yamen Moghrabi

On a fragmented map, the head of the Syrian regime, Bashar al-Assad, set the date for the People’s Assembly (parliament) elections in Syria on May 11 through a decree reported by the official Syrian news agency (SANA). As the door for candidacy opened, the election committee received 1,631 applications for candidacy to the council, and the number increased several folds by the end of the candidacy period.

On road dividers and streetlight poles in streets that haven’t seen government electricity for years, candidates posted their photos and election campaigns while many Syrians ignored the event, and others boycotted it.

Germany recently opposed the electoral process itself, and it is expected that other European and American countries will oppose it as well. Observers see that this is because the elections contradict UN Resolution 2254, which calls for a peaceful transition of power to resolve the long-standing conflict in Syria for 13 years.

Knowing that the elections will not be accepted, the regime continues to promote them within a constitutional framework, which experts interpret as messages to the outside world, not an internal affair.

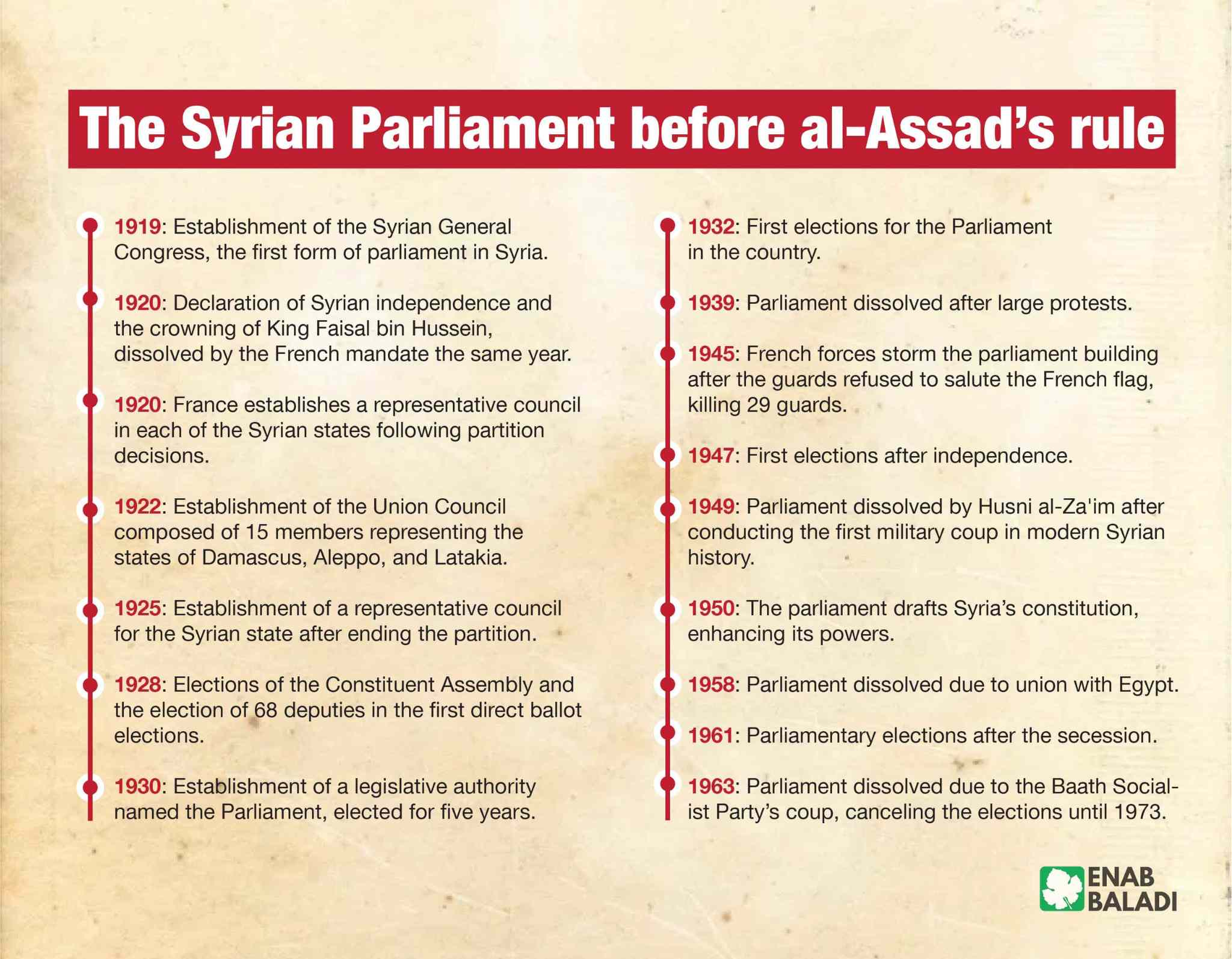

Over 60 years of the Syrian regime’s rule, every electoral process has been a legitimacy exercise for the ruling system. In none of these occasions were the elections seen to produce legitimate candidates.

Researchers see that the Syrian regime deals with the current elections by defining itself as the “legitimate authority,” even though Americans and Europeans will never recognize this legitimacy. It is aware of this, but aims to send messages that it represents a segment of Syrians; consequently, another segment remains excluded from political representation.

The regime tries to convey to the outside world that its rule is strong and capable of organizing elections, but it treats the resulting percentages and numbers as a means for negotiation.

The presidential elections organized by the regime in May 2021 resulted in Bashar al-Assad winning after receiving 13,540,860 votes, with 95.1% of the valid votes. According to Damascus data, more than 14 million voters participated, without any independent authorities monitoring the voting process and results.

Based on these and other results, the regime interprets the numbers mathematically. Calculating the percentage of votes obtained from the number of Syrians inside the previous elections, it results in about 80% popularity for the regime. Therefore, it negotiates on this basis: 80% for the regime and 20% for others.

In the previous elections, the calculations led to the regime having 70%, so it negotiated the remaining 30%. This has been the approach to electoral processes for years.

In this report, Enab Baladi discusses with experts and researchers the announced elections on July 15, exploring the questionable legitimacy of the electoral authority and the messages intended to be sent amid the stagnation of all political processes involving the parties embroiled in Syria.

Geography doesn’t help

Today, the Syrian regime controls most of Syria’s geography but does not have acceptance in all the areas it controls. Some cities and villages were strongholds of factions opposing the regime, and many of their residents were killed by air or ground strikes from the regime’s military machine.

At a time when the regime cannot push Syrians in its controlled areas to participate in the elections, Syrians residing in northwestern Syria, where the last strongholds of the Syrian opposition with millions of internally displaced persons and residents exist, are also outside the electoral equation.

In northeastern Syria, where the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES) is backed by the USA, the region’s inhabitants were prevented from participating in the elections. Previously, the head of the Democratic Union Party (PYD), Saleh Muslim, stated there would be no participation in the People’s Assembly elections because the Autonomous Administration has its social contract and local systems and laws that dictate non-participation in the People’s Assembly elections. He emphasized that ballot boxes would not be placed in areas controlled by AANES.

The Democratic Union Party is one of the prominent Kurdish parties accused by international entities of attempting to secede from Syria. It forms the foundation of the Autonomous Administration that has expanded in northeastern Syria since 2015, with American support.

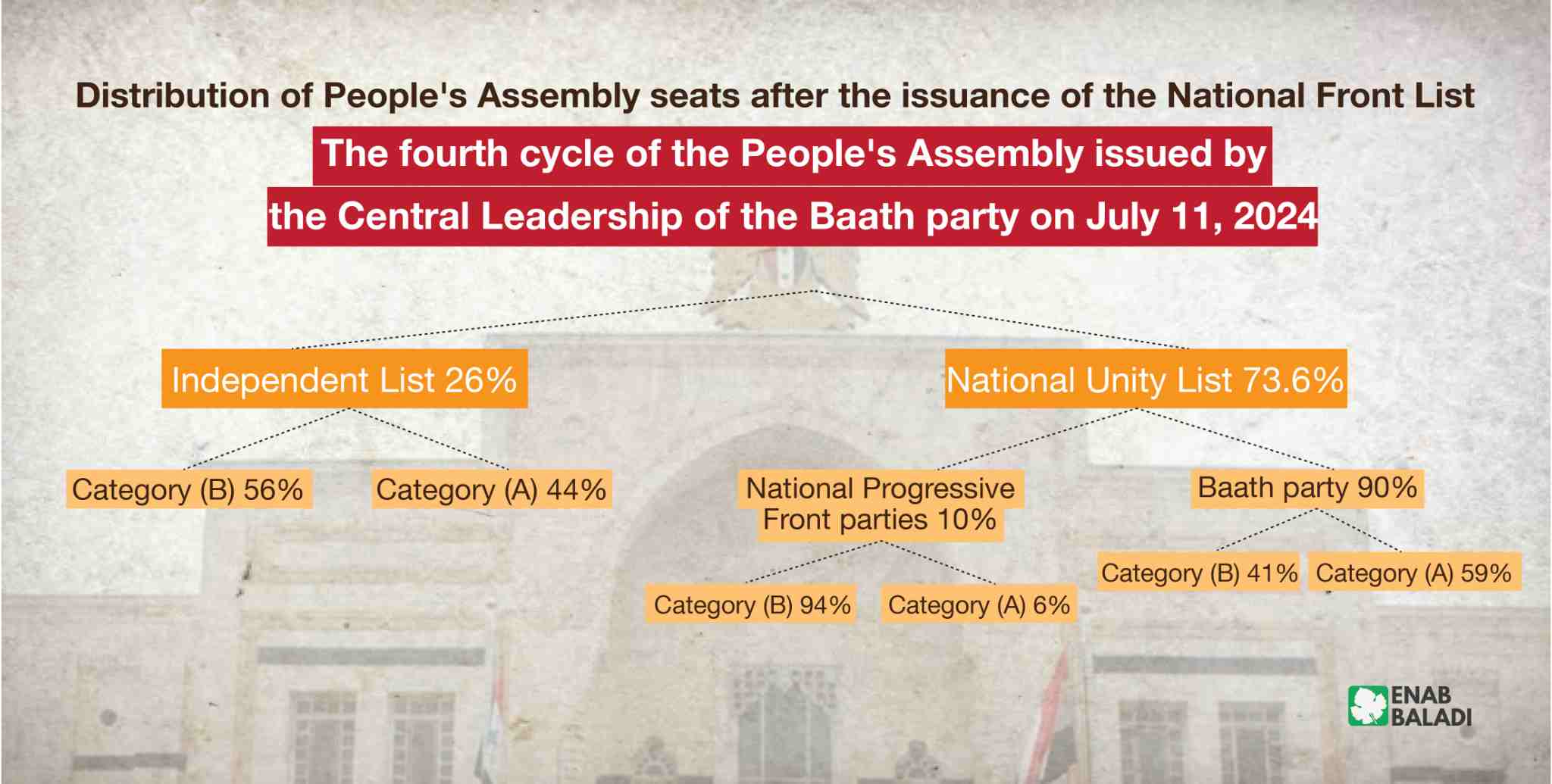

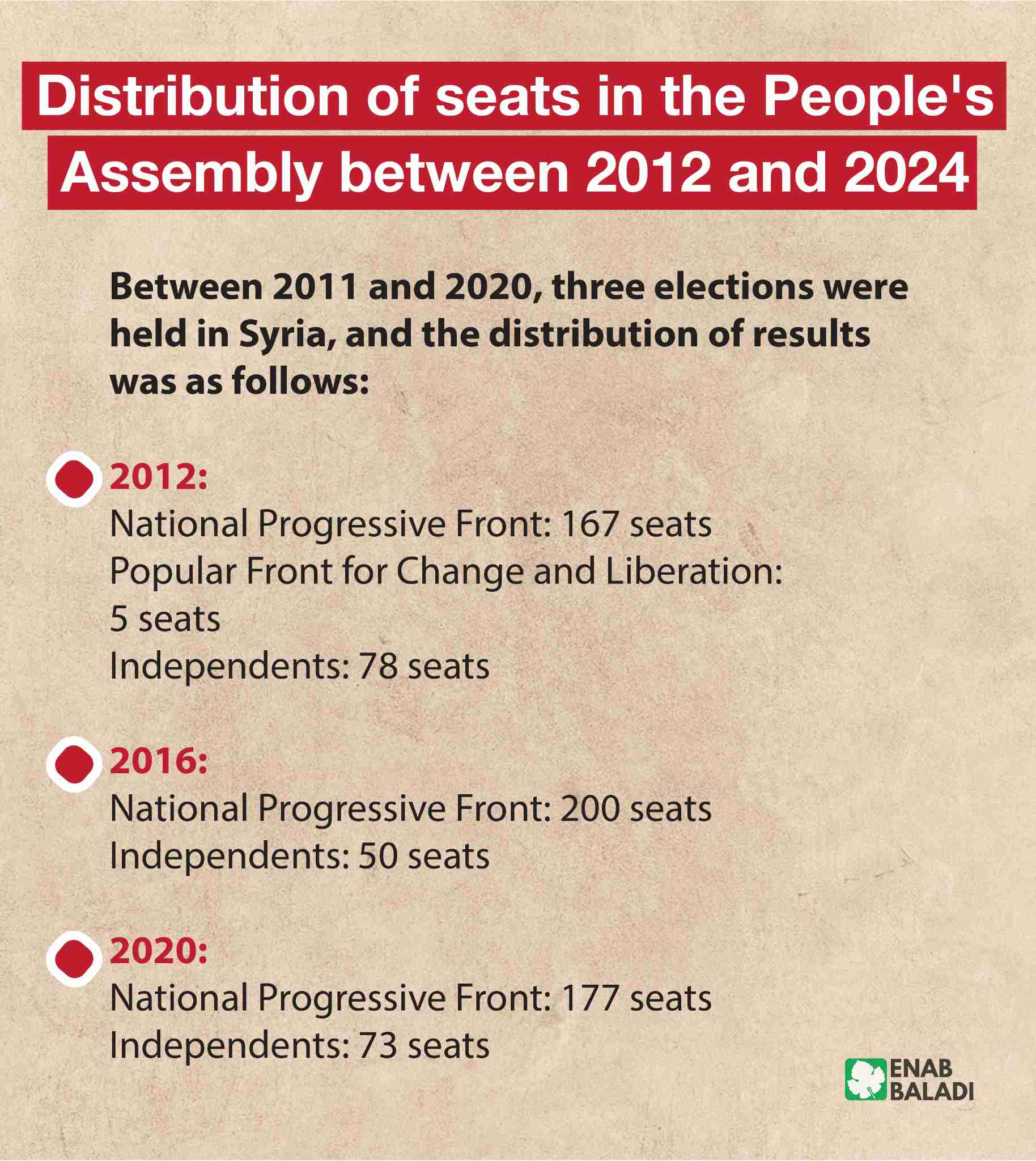

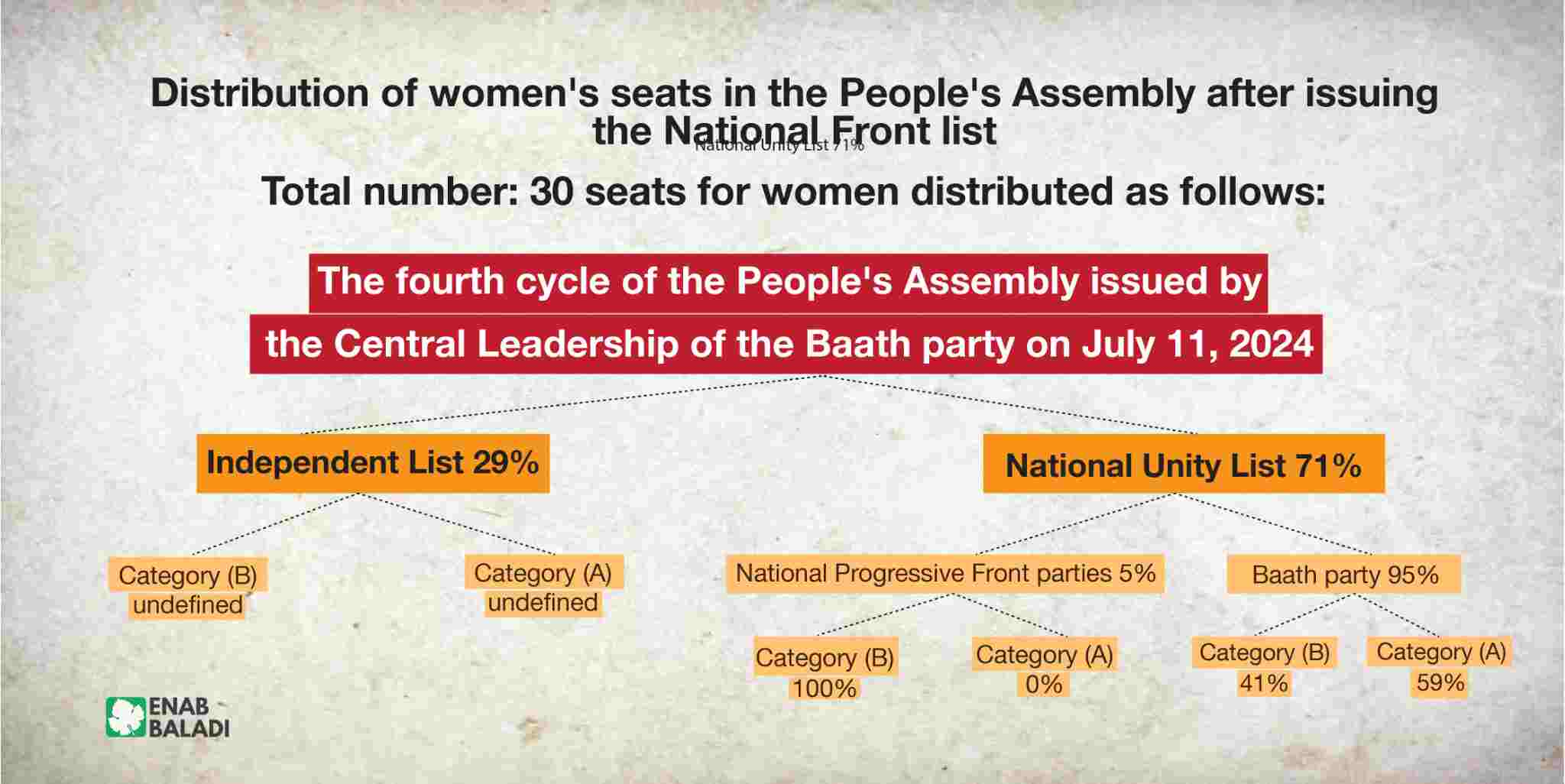

The regime conducts the upcoming People’s Assembly elections with its quota of 183 out of 250 council members. The regime’s quota is determined by the Baath party and other allied formalistic parties (166 seats for the Baath party and 17 seats for the rest of the parties) known as the National Unity List, with 67 seats left for independents.

The upcoming election is the fourth the regime has held in its controlled areas since the revolution erupted in 2011, amid international and local skepticism about their fairness and the fairness of the previous presidential elections in 2021.

The south protests

In the context of the peaceful protest movement opposing the Syrian regime for about a year, activists in As-Suwayda governorate, southern Syria, launched a mobile media campaign at the beginning of this July under the slogan “No to Elections,” in rejection of the electoral process.

The local Al-Rased news network reported that As-Suwayda activists aim through this campaign to encourage people to boycott the elections, considering them “superficial and the winners are already known, and participating in them solidifies the dictatorial manner in which the electoral process is conducted.”

The campaign organizers pasted posters on walls and electric poles, in addition to hanging banners and organizing protests to convey their message urging people to boycott the elections.

The campaign organizers posted stickers in cities and towns, including Shahba, Salim, Qanawat, Mafaleh, al-Jnaynah, al-Surah al-Saghira, Arajeh, Salkhad, and others, aiming to include the rest of As-Suwayda governorate.

The banners and posters carried several slogans, notably: “For the children of Syria, boycott the elections,” “The real parliament is the people’s voice, not the regime’s,” “The parliament is born after the regime is toppled,” “My fellow citizen, your vote is your dignity, do not grant it except to those who safeguard the dignity of the nation and the citizen,” and “Boycott the elections for the future of your children.”

The stance is no different for the people of Daraa governorate in southern Syria, which had been a significant military and political opponent to the regime before 2018.

A large portion of the province’s population opposes any elections held by the regime, as the majority previously opposed the presidential elections in 2021 and the preceding parliamentary elections, just as with the latest elections.

International objection based on resolution 2254

Germany expressed its opposition to holding any elections in Syria at the present time, including the Parliamentary elections. The German envoy to Syria, Stefan Schneck, said on July 10 that Germany does not support holding elections in Syria now.

He explained that “free and fair elections are a crucial part of resolving the conflict and establishing peace in Syria, but the conditions are not yet right.”

According to Schneck, via “X,” Germany supports the full implementation of UN Security Council Resolution No. 2254, which calls for holding elections after adopting a new constitution, but calls on all parties to facilitate a Syrian-led, Syrian-owned political process to agree on a new constitution and to implement Resolution 2254.

Holding elections at this time in Syrian territories will not move the political process forward but will rather solidify the current situation, characterized by long-standing conflict and division, according to the German envoy.

He also called on all parties to refrain from any actions that would jeopardize prospects for a peaceful resolution to the conflict in Syria and the power transition as called for by Resolution 2254.

The United States has not yet taken a position on the elections, but it previously commented on elections that the Autonomous Administration intended to hold (postponed until next August). Vedant Patel, the deputy spokesperson for the US Department of State, said on May 30 that the United States maintains its position that any elections held in Syria must be “free, fair, transparent, and inclusive.”

The Syrian People’s Assembly announces the candidature of a woman for the presidency – April 20, 2021 (CNN)

Under questionable authority

The international view that any elections in Syria are illegitimate is not just tied to the upcoming Parliamentary elections but has overshadowed the presidential elections held in Syria in 2021, since they took place outside the framework of UN Resolution 2254.

The foreign ministers of the United States, France, Britain, Germany, and Italy condemned the elections held in Syria at that time through a joint statement, stating that “free and fair elections must be held under UN supervision in accordance with the highest standards of international transparency and accountability.”

The statement added that fair elections should be conducted with UN monitoring and allow all Syrians, including displaced persons and refugees in the diaspora, to participate in a safe and neutral environment, considering that “without these elements, the elections are illegitimate and do not represent progress towards a political settlement.”

Swedish researcher Aron Lund, an expert on Syrian affairs at Century International, believes that under the current regime, parliamentary elections will not help achieve the provisions of Resolution 2254, nor will they be widely accepted abroad.

Lund told Enab Baladi that, based on western rejection and the continued process of elections in Syria, it cannot be believed that the number 2254 forms part of the regime’s calculations.

Lund pointed out that the regime is simply trying to continue doing what it has always done.

On the other hand, researcher Sam Heller of the Century Foundation believes that countries opposing the regime will reject the upcoming elections, as they have done in the past, while the regime continues to believe that the western opinion is “just interference in Syrian domestic affairs.”

Heller told Enab Baladi that the regime’s interest in holding the elections on schedule is to show continuity and stability to its domestic and international audience, and to send a message to external enemies that it will not succumb to pressure and will not allow interference in Syria’s sovereign affairs.

Elections in Syria, in particular, send political messages that can be gleaned from the announced proportions of independent candidates in each electoral cycle.

According to officially announced results by the Syrian regime government for the elections expected to be held in mid-July, independents were granted 67 seats in the People’s Assembly out of a total of 250 seats.

In the 2020 Parliamentary elections, the ruling Baath party held 166 seats out of 250 in the Assembly, constituting 66.4%, while other parties of the National Progressive Front held 17 seats, comprising 6.8%, and independents held 67 seats, making up 26.8%.

Lund believes that regular, accurate elections are simply part of the natural functioning of the state and government, even though they are neither free nor democratic at all in Syria, but they serve a certain function.

Elections allow the regime to refresh patronage networks and reward its supporters. We see this in the integration of influential businessmen and tribal leaders into each successive parliament since the beginning of the war, as militia leaders have also occupied parliamentary seats.

Aron Lund, Researcher on Syrian affairs at Century International

The researcher believes that there is some limited competition for seats, not through voting but through behind-the-scenes negotiations over positions in the regime-dominated and supported candidate lists.

Although parliamentary elections are not very important to the regime’s government, they are part of the normal functioning of the state, so canceling or postponing them would send a signal that something is wrong, according to Lund.

Lund also said that maintaining the electoral schedule helps sustain the appearance of legal and popular legitimacy. It helps al-Assad’s rule appear stable and effective, even if it does not seem democratic.

He added that al-Assad needs a “duly elected parliament” to change the constitution in the future, to legitimize his continued rule. It is obvious that the whole process is merely “decorative,” but he will persist in making it appear orderly and lawful.

In line with attempts to rehabilitate the regime

Typically, any parliamentary elections aim to improve the current conditions in the country, but that is not the case in Syria, particularly in areas controlled by the regime, which suffer from severe shortages in services and a collapse of basic infrastructure, not to mention the grinding economic crisis amid a tight security grip.

On the other hand, the People’s Assembly elections follow “superficial” changes announced by al-Assad in recent months, whether on the military front with his pursuit of “forming a professional army,” or removing economic figures, merging security branches, or developing the ruling Baath party.

According to the current Syrian constitution, implemented since 2012, and within Article 12, “the democratically elected councils at the national or local level are institutions through which citizens exercise sovereignty, building the state, and leading the society.” Article 74 states, “Members of the People’s Assembly have the right to propose laws and direct questions and inquiries to the ministry or any of the ministers.”

Article 58 of the constitution states that “each member of the assembly represents the entire people, and their mandate cannot be restricted by any condition. They must exercise it guided by their honor and conscience.”

Judging by these three articles concerning the legislative institution and its role in accountability and responsibilities, the situation in Syria appears different. Despite the regime portraying itself as adhering to a democratic process, it emphasizes solidifying al-Assad’s power amid calm fronts and restoring some regional balance, especially since the People’s Assembly played a direct role in bringing Bashar al-Assad to power in 2000 after his father Hafez al-Assad’s death, through a quick amendment of the previous constitution, lowering the presidential age from 40 to 34 years (later amended back to 40 years in the 2012 constitution).

Given the specific role of the assembly under al-Assad’s rule and the recent changes in security, military, and economic sectors, questions arise about al-Assad’s interest in these elections and whether they are genuinely a gateway to change or a new step to consolidate his power.

Bassam Quwatli, head of the Syrian Liberal Party, believes the Syrian regime is keen to appear as the “people’s choice.”

Quwatli told Enab Baladi that the regime is interested in demonstrating adherence to the democratic process and thus adhering to holding elections on time. The results of the upcoming elections are considered “guaranteed” due to several reasons, chiefly fear and security control, reserving seats for workers and farmers, and the list system that gives the regime an advantage, thus reproducing the current system.

Although hope for change under al-Assad’s recent moves is non-existent, the elections are accompanied by a process of “rehabilitating al-Assad,” a process sponsored by the Arabs (through the Arab Initiative), or through unannounced American approval and European alignment, according to Quwatli.

Opposition Syrian politician Yahya Aridi told Enab Baladi that what al-Assad is doing today regarding the People’s Assembly elections is done “in a different and deceptive way” that aligns with the current wave titled “rehabilitating the regime,” based on the fundamental demand from the United States to change his behavior.

He added that considering the People’s Assembly as a legislative authority is of no real value, but legally and constitutionally it is hypothetically a legislative body. It legitimized al-Assad’s presence in power in 2000 by amending the constitution, and its members are controlled by the main force governing the country, so you won’t find a free voice inside it. If any exist, they do not dare speak, except in rare experiences.

Internal arrangements

Over the past months, al-Assad has sought to reorganize the security, military, and economic sectors, and the Baath party. It seems today is the time to exploit the People’s Assembly elections as part of al-Assad’s path to present a different image, or that is sponsored by regional entities.

The regime, in official media broadcasts, seems attentive to these details and has devoted considerable space to them in recent times, especially concerning the internal elections of the Baath party, which preceded the People’s Assembly elections.

Opposition figure Yahya Aridi described these moves as being carried out in an “elegant and deceptive manner,” noting that the current wave does not signify any forthcoming change.

Aridi told Enab Baladi that the change does not include the essence, methodology, and basic behavior of the ruling system. The same applies to “combating corruption” and restructuring the military, while the security situation remains pervasive, as well as the changes he made in the Baath party. All these points have started to be applied to the legislative apparatus in the country, which is the People’s Assembly, according to Aridi.

On the other hand, Bassam Quwatli sees the regime working to show that its rule is stable, and the situation is under its control naturally. It means sending different messages to the outside world, centered around its ability to manage change in Syria.

The regime’s messages aim to convince the world to accept and deal with al-Assad, as he is a prevailing reality, and there won’t be any change except through him and in his interest.

Bassam Quwatli, Head of the Syrian Liberal Party

Quwatli told Enab Baladi that any field change in Syria approved by the regime should only serve its interests. The regime does not propose any democratic transformation or power-sharing but rather changes that reproduce the same as before 2011.

if you think the article contain wrong information or you have additional details Send Correction

النسخة العربية من المقال

-

Follow us :

Bashar al-Assad in Syria’s People's Assembly, 2016 (The New York Times)

Bashar al-Assad in Syria’s People's Assembly, 2016 (The New York Times)

A

A

A

A

A

A

More In-Depth

More In-Depth