This investigative report delves into the conditions of Syrian detainees in Libya, contrary to international law, and the human rights violations within migrant detention centers, especially those under the Stability Support Apparatus.

The investigation, carried out by Syria Indicator in collaboration with Enab Baladi, provides glimpses inside some centers and documents the inhumane conditions of arbitrary detention and the physical and psychological torture of detainees by various means, without referring them to the judiciary. Detainees are extorted before and during their detention, with their families being extorted for their release for money. The investigation reveals coordination in some cases between human trafficking networks and the authorities and militias in both eastern and western Libya.

When Ali left Syria two years ago, he knew that his journey to Europe entailed the risk of illegally crossing the sea from Libya. However, the 21-year-old did not imagine that he would endure hardships even before embarking on that journey! Ali was detained in Libya, where he was beaten, tortured, insulted, and fell ill, worsening his health condition, as he already suffers from a heart condition.

“The jailers intentionally hit detainees on their faces so that the bruises and slaps serve as a deterrent for anyone thinking of resisting them again,” says Ali in his testimony about the Libyan migrant detention centers from which he eventually escaped, but with physical injuries that required time to heal, and psychological trauma that still haunts him today.

Ali had departed from the city of Quneitra in southern Syria in August 2022, hoping to reach Europe through Libya, paying $3,700 which included the plane ticket to Libya, temporary accommodation there, and the sea crossing fee, as per his agreement with a member of the smuggling network. After a few days of arrival, elements of the Libyan Department for Combating Illegal Migration (DCIM), raided the temporary accommodation place and took him to a detention center along with 40 migrants of different nationalities.

Thousands of detainees

In February, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) stated that the number of detainees in Libyan detention centers had reached 5,000 people, 30% of whom are children living under extremely harsh detention conditions with limited access to basic needs.

These individuals are accused of illegal immigration, which justified the detention of thousands by the Libyan Stability Support Apparatus, directly responsible for the detention centers in the western Libyan government. They pack hundreds of them into small cells, according to testimonies obtained by Syria Indicator/Enab Baladi.

After about 13 years of conflict, human rights violations committed by armed groups and militias remain pervasive, as political elites and myriad quasi-authorities compete for legitimacy and control of territory, according to a report by Human Rights Watch published in September 2023.

On the subject of migration, Abdoulaye Bathily, the outgoing head of the United Nations Mission to Libya, described Libya as “increasingly resembling a mafia state dominated by a number of groups involved in many smuggling operations, including human trafficking.”

Currently, Libya is controlled by two governments: one in the west, internationally recognized and known as the Government of National Unity, and the other in the east, not internationally recognized, and loyal to retired General Khalifa Haftar.

The conflicting parties in Libya compete for “more power, more control over the country’s wealth,” according to Bathily.

Ali stayed with 400 detainees in one section of the Ain Zara detention center, south of the capital Tripoli, mimicking a large warehouse crowded with worn-out mattresses strewn next to four neglected bathrooms, prompting him to “sleep on the ground instead of the bed because of insects and foul odors.”

The young man suffers from supraventricular tachycardia, which causes episodes of shortness of breath, chest pain, and rapid heartbeats, and his detention conditions worsened his health status.

Throughout his detention, Ali and his fellow detainees experienced numerous violations. He witnessed a specific practice repeating weekly: a group of men in military uniform, identified later as members of the Stability Support Apparatus, would enter to conduct searches and confiscate anything of value, including rings, watches, phones, chargers, and more.

The searches were conducted in a very humiliating manner, intruding upon the detainees’ bodies in front of everyone. No one could hide anything from them; anyone who tried was dragged outside and beaten severely, with only their screams heard.

Ali, one of the survivors of Libyan detention centers

According to Ali’s testimony, African migrants constituted the majority of detainees, clustering into groups to protect each other and preventing guards from searching and confiscating their belongings, until “the day that left a mark in the memory of everyone in the detention center. The jailers ordered all Syrians and Egyptians out into the yard, leaving around 250 African migrants inside,” Ali recounts, adding, “They entered with sticks and trained dogs.” The detainees’ screams rose. After finishing their assaults, the guards ordered the rest of the detainees back inside. Ali saw “men writhing in pain and crying on the ground, their dark skins bruised with blue marks from stick strikes, and bloodstains from the prison dogs. It was a lesson for anyone thinking of disobeying them.”

Cross-border networks, Coordination between rival forces

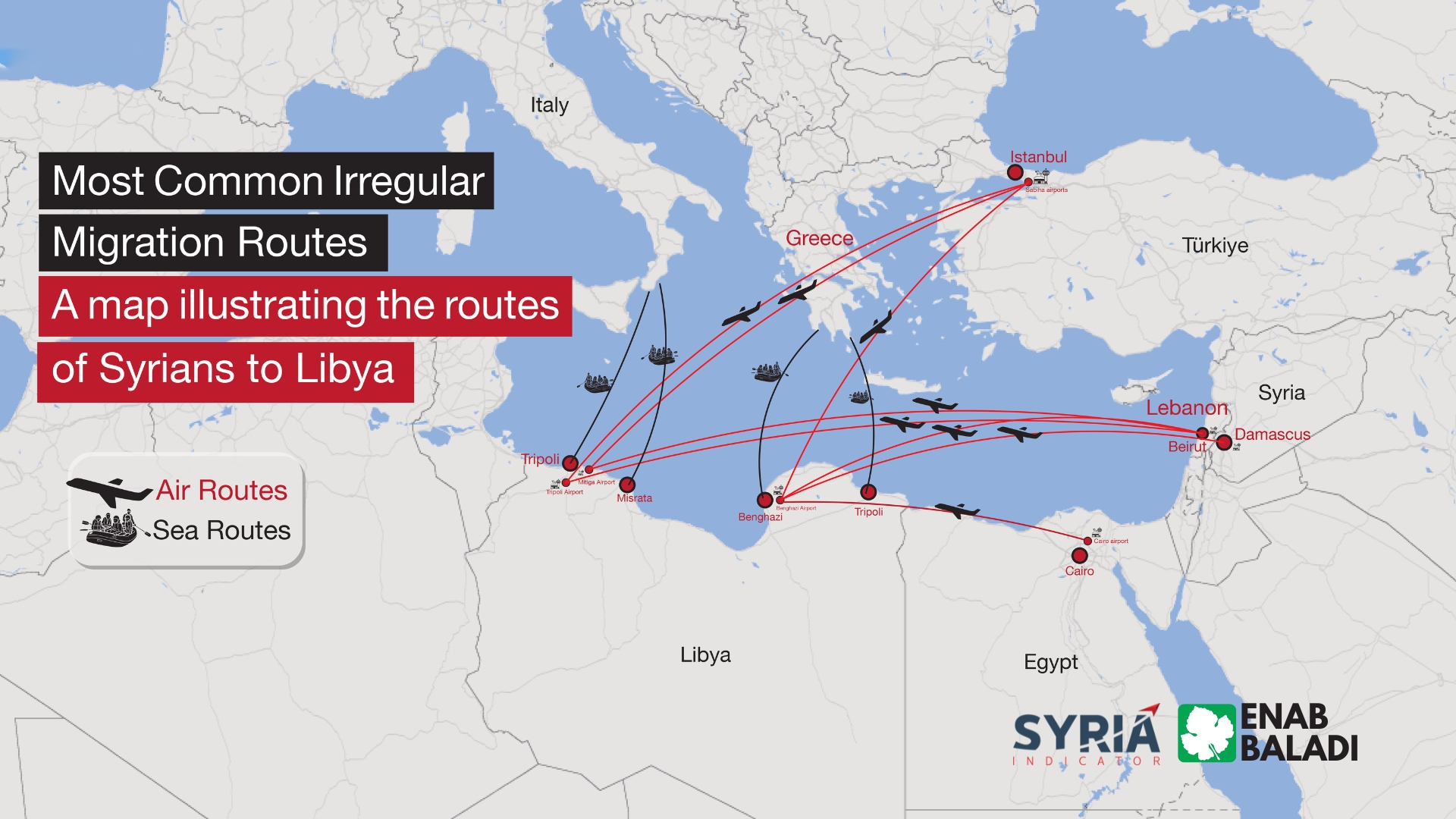

Youssef, over 25 years old, a native of Homs in central Syria and a father of two children left in Lebanon, set out in search of work in Turkey. In June 2023, with the intensification of deportation campaigns from Turkey, Youssef departed via Istanbul Airport to Libya after contacting a “human trafficker” who promised a safe journey to Europe for about $1,600.

Youssef’s testimony reflects the vast size of the human trafficking network he dealt with, spreading across many countries and coordinating even between rival forces within Libya. Through Jordanian individuals, the young man was introduced to a “representative” from Homs working with smugglers. The “representative” secured Youssef’s visa and security clearance, along with others who accompanied him on the journey. Another “representative” received him at Benghazi Airport in Libya, finishing entry procedures into Libyan territories.

Despite the division of control in Libya between East and West, each part managed by a government with its devices and groups and active militias in conflict, human trafficking networks operate seamlessly across these geographies. Youssef arrived at Benghazi Airport under the control of the eastern Libyan government (Khalifa Haftar) and was received by a “representative” who then arranged his transportation to Sirte. Youssef and eight others in the same situation traveled in one vehicle, intercepted at a checkpoint at Sirte’s entrance, and then handed over to the Department of Combating Illegal Migration where they were detained for two days before being released.

The group reconnected with the “representative,” who directed them to the city of Misrata, under the western Libyan government (Abdul Hamid Dbeibeh). There, they rented a room in a hotel for a week until Youssef’s promised journey to Europe in July 2023 approached. Youssef, along with others, was placed in a storage facility, subjected to beatings, starvation, and insults. The storage room housed 204 people, including 32 Syrians, according to Youssef’s testimony. They slept in shifts since the room could not accommodate them all at once. There was one toilet and zinc roofs under Libya’s intense heat. Youssef and his group spent 27 days in that storage facility before being transported with 107 others in a sand transport truck and then by a rubber boat to a dilapidated trawler (fishing boat). Youssef and 75 others crowded into the fish cooling tanks amidst its chilly and suffocating odors.

Inside Libya, we were mere ‘cargo’. The smugglers put us in the car without telling us where we were going, changing the route at their will. The smuggler was weak and frail, but he controlled us with a weapon and the backing of his government-supported group, while we had no one. If we were killed, no one would even know.

Youssef, a survivor of the Libyan detention centers

Youssef explained to Syria Indicator / Enab Baladi that the trawler was clearly damaged, water leaking into its hull. It was equipped with a rudimentary device to pump the water out again, making Youssef and those with him in the tanks feel the danger of sinking from the outset.

After about two hours, the passengers noticed the retreat of two traffickers, the captain, and his assistant, who boarded a small boat traveling alongside the trawler, leaving it without a commander! Shortly afterward, patrols belonging to the Libyan coast guard of the eastern Libyan government arrived and detained all the passengers, who realized that the entire affair had been coordinated between the traffickers and the coast guard.

East, west… and vice versa!

The patrol members confiscated all the possessions of the asylum seekers, including money, electronic devices, and identity documents. They then transported everyone to the city of Sirte and handed them over to the “frogmen” unit of the naval forces under the government of Eastern Libya. Youssef felt somewhat relieved that he was detained in Sirte (government of the East) and not in Tripoli (government of the West), which is known for its harsher prisons.

A few days later, Youssef and his companions were asked to get ready, and then they were crammed into a few buses and transported on a nine-hour journey without food, drink, or even a bathroom break. Upon arrival, the detainees discovered they had been taken to Tripoli, specifically to the Triq al-Sikka detention center. They stayed there for a period without any investigation and were not referred to court. Instead, their passports were returned to them, and they were moved to Ain Zara prison under the government of Western Libya.

Syrians rank second

In 2023, around 60,000 asylum seekers crossed the central Mediterranean route. According to the European Border and Coast Guard Agency (Frontex), 41% of all crossings to Europe were through this route, making it the busiest and deadliest migration route. Boats depart from Algeria, Egypt, Libya, and Tunisia, according to the European Council on Refugees and Exiles (ECRE).

The communications officer at the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), Sanne Biesmans, explains that the agency “conducts visits to detention centers run by the Department for Combating Illegal Migration (DCIM) across Libya in coordination with Libyan authorities.” However, these visits do not include centers run by the Stability Support Apparatus (SSA), which was established in January 2021 and created several detention centers that the UNHCR teams or other UN agencies and international organizations cannot access.

Biesmans confirms to Syria Indicator/Enab Baladi that these visits have led to the documentation of data for 118 Syrian detainees, though these numbers are not final and can change as individuals may be released or detained between visits conducted by the UNHCR teams.

Syria Indicator/Enab Baladi reached out to the Stability Support Apparatus through their official email and Facebook page, inquiring about the number of Syrians in their detention centers and their conditions and expected fate, but the investigation team had not received any response by the time this report was published.

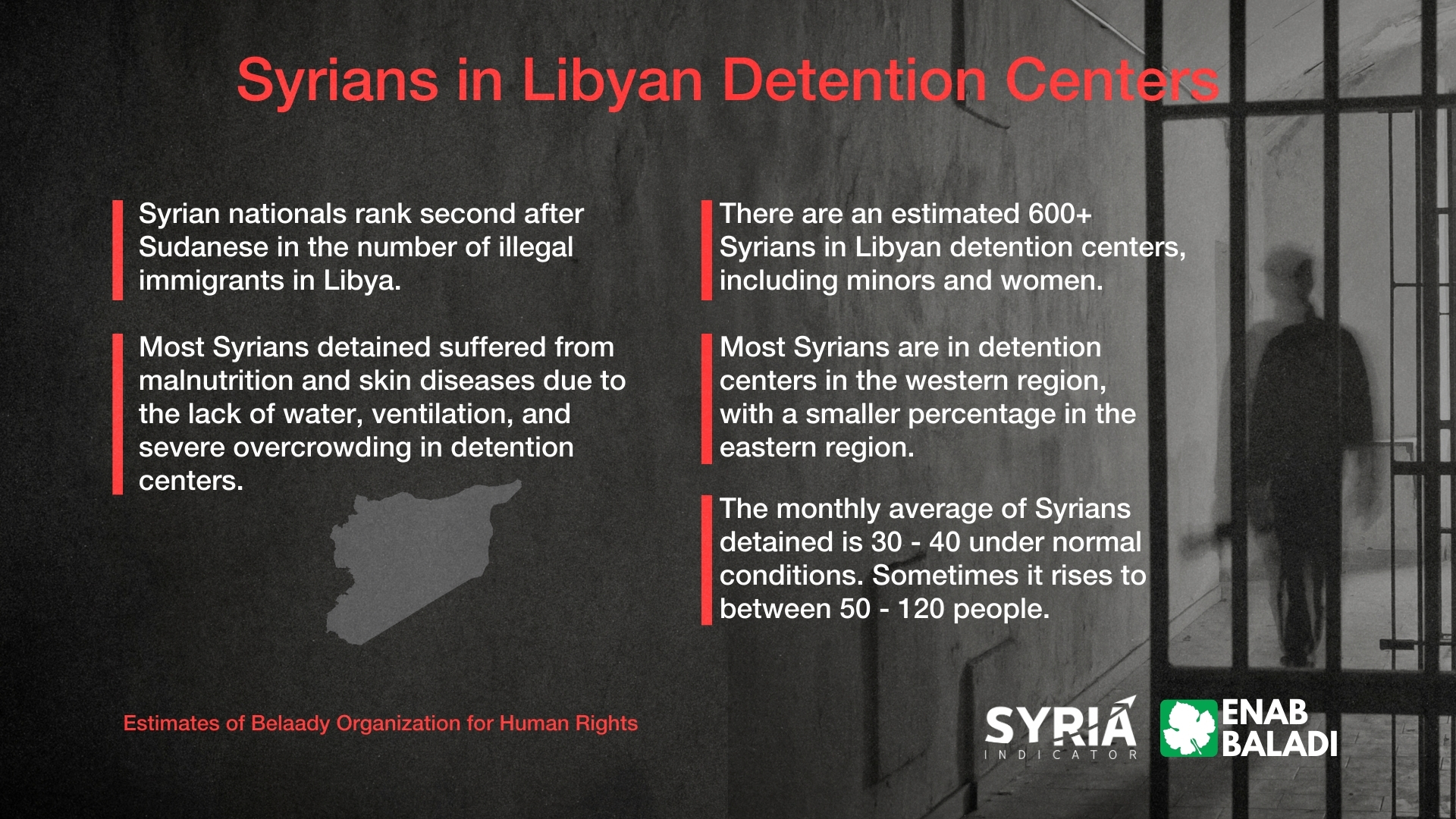

According to estimates by the Libyan human rights organization “Belaady,” the number of Syrians in Libyan detention centers exceeds 600, including women and children. Most Syrians are detained in the western part of Libya, with a smaller percentage in the eastern part, and some are held by the Libyan Border Guard, although they are “not authorized to detain them,” according to Tarik Lamloum, the head of the organization.

Lamloum confirms to Syria Indicator/Enab Baladi that “Syrians have ranked second after Sudanese in the list of nationalities of illegal immigrants in Libya in the last two years, with a monthly average of 30 – 40 Syrians entering detention centers under normal conditions, sometimes increasing to between 50 – 120 people.”

Militia sponsored by the Prime Minister

The Stability Support Apparatus was established by a government decision in January 2021, led by Abdel Ghani Al-Kikli, who, according to Amnesty International, has a documented history of international crimes and serious human rights violations committed by militias under his command.

Al-Kikli, known as “Gheniwa,” is considered one of the most influential militia leaders in Tripoli, according to Amnesty International‘s human rights report.

The Stability Support Apparatus receives its funding from the Government of National Unity, which governs western Libya and is based in Tripoli, headed by Abdul Hamid Dbeibeh. This has “allowed the militia to evade punishment for killings, intercepting migrants and refugees, detaining them arbitrarily, practicing torture, and enforcing forced labor, among other serious human rights violations,” according to Amnesty International. Ministry of Interior sources in Tripoli confirmed to Amnesty International that “the operations of the Stability Support Apparatus are not supervised by the Ministry but report administratively to the Prime Minister, and there is no legal basis for the apparatus to engage in operations intercepting individuals.”

Abdel Ghani al-Kikli, head of the Stability Support Apparatus – February 22, 2023 (Facebook/Stability Support Apparatus)

Inside detention centers

Youssef and his companions were transferred to Block Eight in Ain Zara Prison in Tripoli, which housed about 600 detainees of various nationalities, accused of “illegal immigration.”

The overcrowded detention center lacks clean water and hygiene supplies, and in the block, there are 14 toilets without doors, half of which are out of service. The food is scarce and of poor quality, with 600 detainees taking turns using only seven plates. Groups eat one after another using the same plates, which are only washed once before each meal with toilet water without any cleaning agents. Ventilation is almost non-existent inside the block, and with the intense heat of the summer months, the situation becomes catastrophic.

Most of the Syrians detained suffered from malnutrition and skin diseases like scabies and some allergies due to the lack of water and ventilation in this place, in addition to the extreme overcrowding in most of the places they were detained, and the inhumane conditions for detainees of all nationalities.

Tarik Lamloum, Head of Belaady Organization

In these conditions, skin diseases spread heavily, and cases of fainting and exhaustion due to severe malnutrition are common, according to Youssef, who lost about 12 kilograms of his weight during his detention. The young man says, “I contracted scabies and lice like many others. I saw detainees around me scratching their skin until it bled.”

The hand of an illegal immigrant suffering from skin diseases in Libyan detention centers (Belaady Organization/Tarik Lamloum)

Starvation, rape, and killing

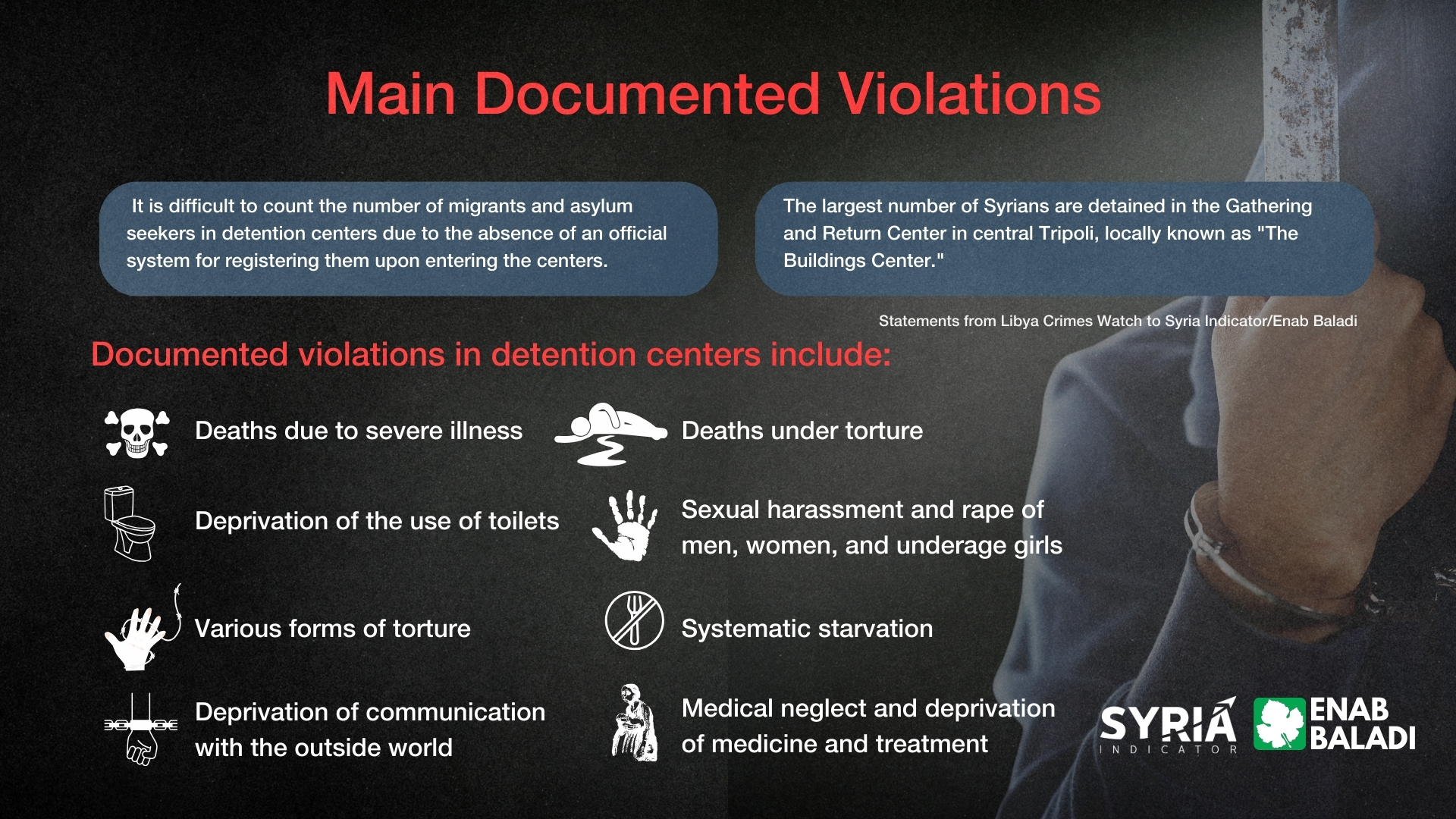

The Libya Crimes Watch (LCW) organization, an independent human rights organization, confirms the difficulty of counting the number of migrants and asylum seekers in detention centers due to the absence of an official system for registering detainees, meaning that the immigration authority affiliated with the Ministry of Interior has no statistics on the number of detainees or their nationalities, according to statements by the organization to Syria Indicator/ Enab Baladi.

Migrants and asylum seekers, both men and women, are subjected to various forms of torture, humiliation, and maltreatment inside detention centers and prisons across Libya.

Libya Crimes Watch (LCW) has documented numerous violations, including various forms of torture, sexual harassment, and rape of men, women, and underage girls alike, systematic starvation, medical neglect, deprivation of medicine and treatment, deprivation of the use of toilets, and deprivation of communication with the outside world. They also documented cases of death due to severe illness and deaths under torture.

In some cases, forced labor of migrants in construction, cleaning, and moving items from one place to another both inside and outside their detention places was recorded. Extortion of migrants was also very common, with large sums of money being demanded in return for their release, which they could not afford to pay, according to the organization.

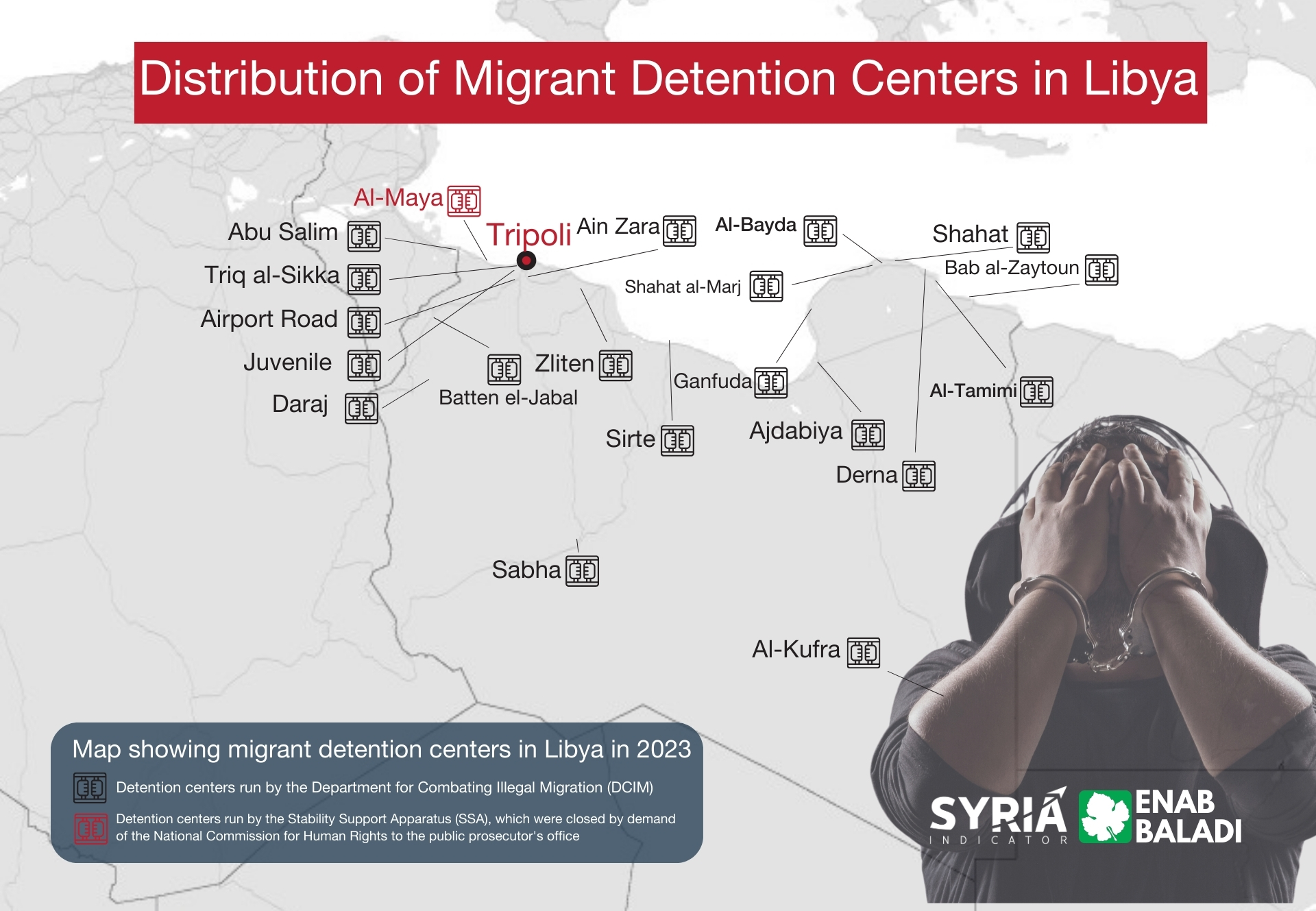

Distribution of detention centers

In Libya, there are 20 official detention centers distributed between the east and west, and according to Libya Crimes Watch estimates, the number rises to 29 centers.

Detention centers, or as the authorities call them “accommodation centers,” are divided into two types: branch centers, which are temporary centers where migrants and asylum seekers are detained for short periods, pending transfer to the main centers that make up the other type.

The situation in eastern Libya is considered “somewhat organized” compared to the west, which has a larger number of centers.

The largest number of Syrian migrants are detained in the Gathering and Return Center in Ghout al-Shaal area in central Tripoli, locally known as “The Buildings Center.” It is one of the largest migrant centers in Libya, with a capacity of about 1500 migrants and is considered one of the centers that witness the most human rights violations and torture and maltreatment.

Libya Crimes Watch

Violated law

Majdi Sharif al-Shaabani told Syria Indicator/Enab Baladi that “Libyan law criminalizes illegal immigration, and there is a law concerned with combating it.” Al-Shaabani, a legal affairs and communication advisor at the Higher Council of State in Libya and an administrator in the legal affairs at the Anti-Corruption Authority, and a professor of public law at the Libyan Academy for Postgraduate Studies, explained that this law “applies to any migrant caught at sea or at land borders, or attempting to migrate illegally, or entering Libyan territory illegally.”

Returning to Libyan laws related to illegal immigration, we find that Law No. 19 of 2010 considers anyone who enters Libyan territory without permission or authorization from the competent authorities, or resides in it, or attempts to cross it to another country as an illegal immigrant.

Although everyone we met had obtained security approval and entered Libya legally.

Every illegal immigrant is punished with imprisonment with labor or a fine not exceeding a thousand dinars, and in all cases, “the foreigner convicted of one of the crimes stipulated in this law must be expelled from the territory of the Great Libyan Jamahiriya immediately after executing the imposed sentence.”

Libyan Law No. 19 of 2010

Al-Shaabani adds that “migrants are detained by the judicial police at the Department for Combating Illegal Migration affiliated with the Ministry of Interior, and then they are presented to the concerned public prosecutor, after which an investigation report is opened, and their statements are taken, after which they are transferred to special illegal immigration centers until a decision is issued against them.”

For his part, Abdul Salam Sarqan, a Libyan lawyer working in an independent office in the city of Zawiya, Libya, says, “In detention, the stages according to Libyan law are investigation, extension, referral to the indictment chambers, and then referral to the judiciary for the trial of the accused.” He adds that “all migrants receive decisions to be returned to their countries, except for Syrians due to the existence of an international law preventing their deportation.”

Sarqan says that all the cases he reviewed “were released either with the guarantee of their passports, or the guarantee of lawyers, or with a financial bail, which is usually a symbolic amount.” However, ten former detainees spoken to by the author of this investigation confirmed that they were not presented to the judiciary, were not able to appoint lawyers or talk to their families, and most of them were released either through the intervention of UN organizations or by paying bribes of hundreds of dollars.

Hard currency “speaks”

Youssef recounts that the detainees used mobile phones for the guards in exchange for money, which was either in dollars or euros exclusively. Some also bought cigarette packs from the guards, paying up to 50 euros per pack.

Youssef’s family contacted one of the “human traffickers” and negotiated with him to release Youssef and his brother from the detention center for a fee of $600 per person, and indeed, they were released after 27 days for the money.

As for Abeer (35 years old), wife of a former detainee, she narrates that her husband had traveled from Lebanon after spending more than ten years there with his family, trying to find a better life for their four children.

Abeer says her husband Ahmed (37 years old) could not work in Lebanon, and with increasing fears of escalating campaigns against Syrians there, “he found himself with only one option, which was smuggling by sea.”

Abeer’s husband traveled in late May 2023 via Cham Wings Airlines from Beirut’s Rafic Hariri Airport, and he was soon arrested in mid-June in Ain Zara prison in Tripoli, after the migration boat he boarded was captured in Sirte while attempting to migrate illegally.

The lady confirms that her husband was not subjected to any investigation, trial, or had his case reviewed. After ten days, he was released thanks to the intervention of the UNHCR, “and he looked terrifying when he got out, as he had lost many kilograms of weight and was in poor health,” she says.

In mid-July, as temperatures rose, we decided to open the windows located in the ceiling of the ward to let in air. Seven young men climbed up and opened the windows, but within moments, the guards entered, took out the seven youths, and beat them until their bodies were swollen.

Youssef, a Syrian survivor of detention centers

Ahmed stayed in Libya for a while, then tried to migrate again, and was detained once more. This time he was transferred to Zawia detention center and stripped of everything he owned, including his identification documents. Everyone with him from other nationalities was deported to their countries, but he remained detained since there is no law permitting his deportation, nor a law that could release him.

Ahmed spent months in the detention center, and was finally referred to the public prosecution. He was released after one of his former detainee friends paid a bail of around $20, according to his wife.

“The courts faced with a dilemma”

The director of the Libyan human rights organization “Belaady”, Tarik Lamloum, explains to Syria Indicator/Enab Baladi the lack of ways to enable detainees to leave, except for filing complaints in some exceptional cases for health conditions, or similar. He explains this by stating that “most of them are detained in western Libya, where the authorities do not recognize the entry procedures approved in eastern Libya.”

He clarifies that “the West operates under special procedures and a local law which states that anyone who entered without identification documents or tried to leave is an illegal immigrant, they are arrested, and their penalty is a fine and deportation from Libya.”

Lamloum confirms that detention centers affiliated with the Department for Combating Illegal Migration of the Ministry of Interior, and those affiliated with the Libyan Border Guard, do not announce the numbers and allow visits only from some governmental organizations, like the National Council for Freedoms, which did not properly diagnose the state of the detention centers and did not address the number of detainees.

Many of the Syrians who were released from detention centers attempted to migrate a second and third time and were arrested. The Belaady organization monitored cases of Syrians who were arrested three times.

According to Lamloum, the courts found themselves faced with a dilemma. They cannot return the Syrians to their homeland because they are covered by international protection, nor can they find any diplomatic or legal means to release them from prison since their initial imprisonment was illegal.

He adds: “There is chaos in the Libyan judicial system as the detention of Syrians violates the law because they come from a conflict and war zone and are among the nationalities included under international protection. Judges are far from a true understanding of Libya’s obligations under international agreements that Libya ratified, and they lack an understanding of the distinction between asylum seekers and migrants.”

Violation of international law

International human rights law applies to all people at all times, not just the citizens of the state, but any individual subject to the state’s jurisdiction or effective control. This means that all migrants, regardless of their status, are entitled to the same international human rights as any other person, according to the UNHCR.

States are obligated under this law to “respect, protect, and fulfill the human rights of migrants,” and this includes refraining from arbitrary detention or torture, or the collective expulsion of migrants.

On January 11, a report by Human Rights Watch (HRW) stated that “human rights in Libya are going through a turbulent year amidst the repression by the divided authorities in the east and west of the country, with armed groups and militias continuing to commit violations against Libyans and migrants without accountability.”

According to the report, migrants and asylum seekers endured inhumane conditions, faced torture, forced labor, and sexual assault during arbitrary detention by the Interior Ministries of both the east and west Libyan governments.

The organization confirmed that “the Justice Ministry detained thousands of people for long periods without trial, in prisons nominally controlled by the authorities but actually controlled by militias.”

On May 14, the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, Karim Khan, reported that the UN unified team in Libya had made significant progress in investigations into alleged crimes in Libyan detention centers between 2014-2020. In his sixth briefing before the UN Security Council, he added that the team carried out 18 missions in three geographic areas in Libya, collecting more than 800 pieces of visual and audio evidence, along with over 30 testimonies, including through interviews.

African Refugee Convention

Libya has not ratified the 1951 Refugee Convention or its 1967 Protocol, but it is a signatory to the 1969 OAU Convention Governing the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa.

The convention defines a refugee as “every person who, owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion, finds himself outside the country of his nationality.”

The convention stipulates that “member states shall not subject any person to measures such as rejection at the frontier or expulsion or returning them, which would compel them to return to or remain in a territory where their life, personal safety, or freedom would be threatened.”

The UNHCR confirmed that Libya has yet to implement the OAU Convention by adopting related asylum legislation or procedures.

Libya ratified the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman, or Degrading Treatment or Punishment in 1989, as well as the Convention on the Rights of the Child in 1993, alongside agreements on maritime search and rescue.

A ward in a migrant detention center recently closed (Belaady Organization/Tarik Lamloum, Organization Head)

Investigation: Fatima al-Mohammad

Editing and drafting: Suhaib Anjrini

Translation: Olaa Soulaiman

Video and infographic: Abdul Moeen Homs

Supervision: Ali Eid

if you think the article contain wrong information or you have additional details Send Correction

النسخة العربية من المقال

-

Follow us :

Illegal migrants inside a detention center in Libya - Syria Indicator/Enab Baladi

Illegal migrants inside a detention center in Libya - Syria Indicator/Enab Baladi

A

A

A

A

A

A

More In-Depth

More In-Depth