“My uncle pointed, with an exaggeratedly trembling and skinny hand, to the large metallic dishes scattered on the rooftops, asking about them. He meant by his question ‘the satellite dishes,’ a scene that was ordinary to me and my generation, but astonishing to a man who spent 25 years in the dark dungeons of an authoritarian regime, absent from sunlight, both literally and metaphorically.”

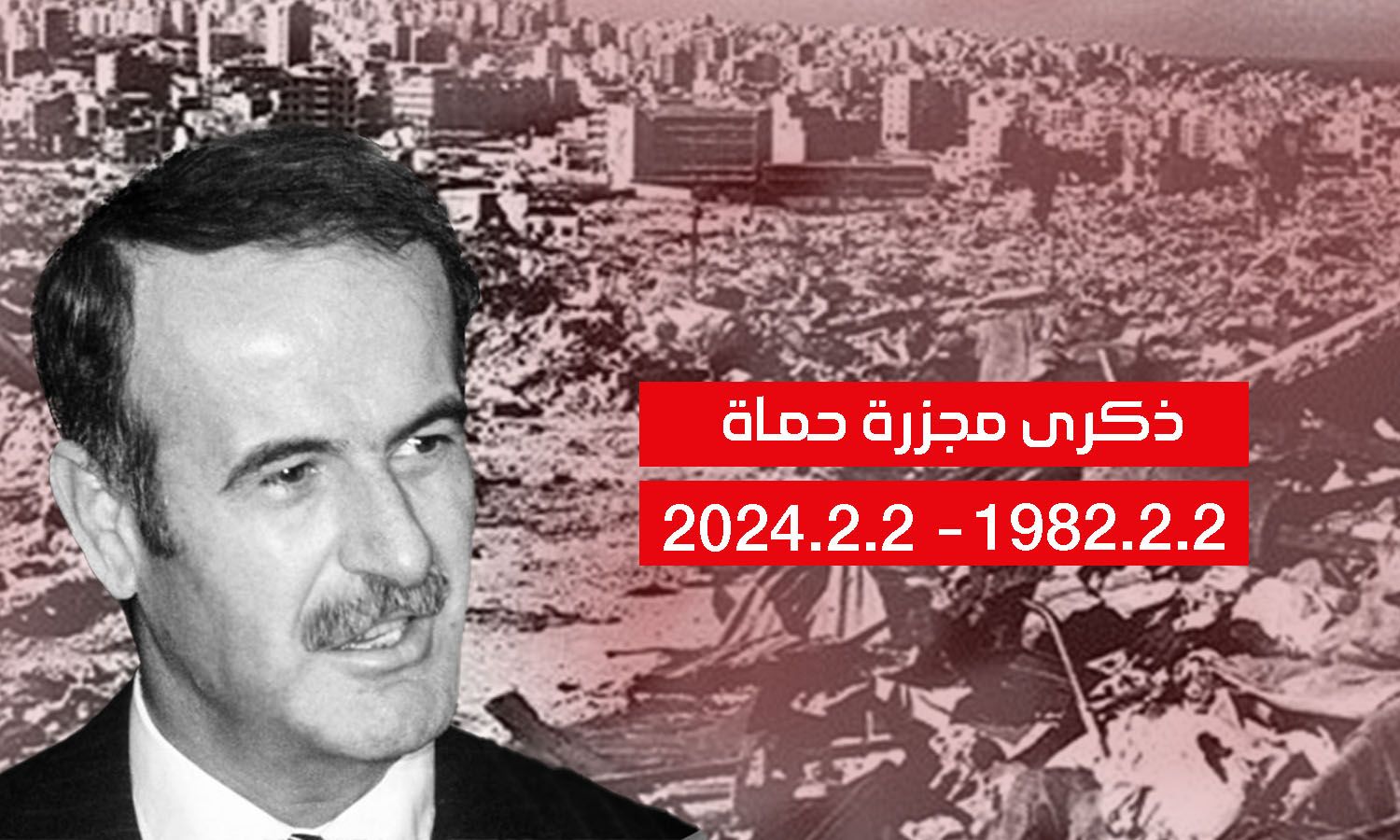

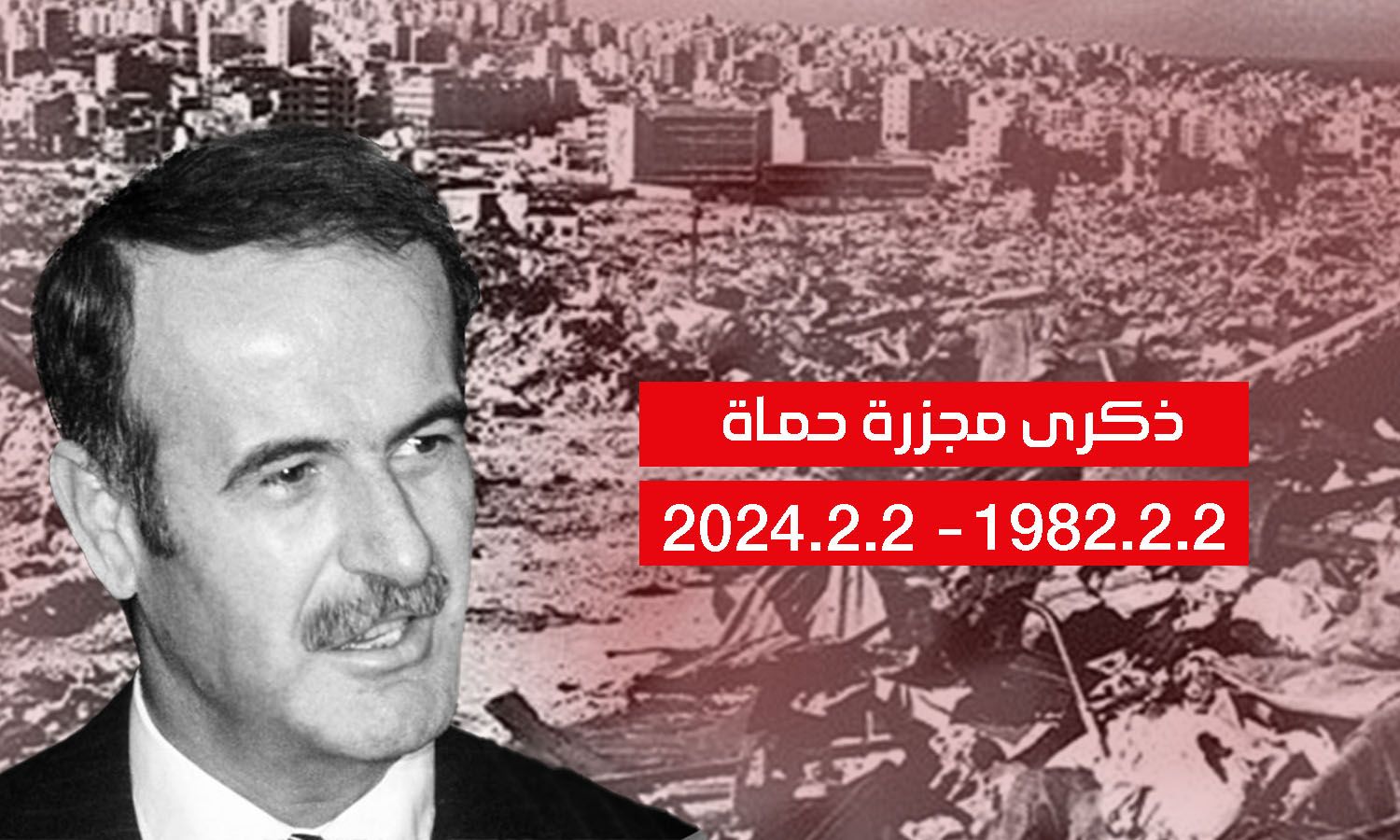

Nour narrates the story of her uncle Nidal, who even after 17 years after being released from prison prefers to use a pseudonym. He was arrested at the age of 25 at the gates of the city of Hama by the Syrian army in February 1982 and spent another 25 years behind bars.

Nidal was working in the capital, Damascus, when word began to spread among the inhabitants of “major problems” in the city of Hama, where his family lived. Due to the reliance on landline phones at that time, which were unavailable in all homes and whose lines were cut off from the city at the beginning of the massacre, Nidal felt compelled to travel to his city to check on his family. He was arrested by the army at the entrance to Hama and disappeared from his family for 18 years, without either side knowing if the other was still alive.

The news of Nidal’s presence in Tadmor Prison reached his family via a relative who met him there in 2000, after he had already spent a full 18 years in arbitrary detention, letting the family know that their son was detained in Tadmor Prison, the largest detention center in Syria.

Nidal completed 25 years of his life underground, deprived of trial because there were no charges or accusations against him. Despite coming close to execution on multiple occasions, he miraculously survived the firing squads and various methods of execution used by the officers, according to what Nour related from her uncle.

In 2007, he was released from detention through a pardon that included him and several other detainees. He was nearly 50 years old by then, and saw a world that was different from the one he left, and a family that was half missing, after part of his relatives had either died in the massacre or due to the passage of time, as described by him.

Talking about the disappearance of one of Nour’s uncles was nearly impossible in her home, where terms like “Hama massacre” and “the eighties events” were forbidden. This is because the older family members who witnessed public executions and brutal shelling that destroyed the city in a matter of days, during which raids and mutilations of the living and the dead took place, did not allow discussions involving any of those words. The younger generation’s information was limited to eavesdropping on the family’s whispered conversations.

Disturbances in the city of Hama date back to 1964, just a year after the military coup that was referred to as the separation from the United Arab Republic.

A protest movement that started from the high schools to the religious sector in the city began in the 1960s, calling for jihad against the ruling party. The response came from the then president of the Revolutionary Council, Amin al-Hafiz, who shelled the Sultan Mosque, violating one of the most sacred places.

The unrest in the city continued with rises and falls, and was dealt with through security measures such as detentions and the disappearance of detainees, sometimes leading to death, and with military campaigns that began in 1964.

Marwan Hadid, a Syrian religious figure from the city of Hama, founded an independent jihadist militant organization separate from the Muslim Brotherhood and Islamic groups in Syria under the name “the Fighting Vanguard.”

The internal publications of the organization were issued under this name until 1979, when the then-leader of the organization, Abdul Sattar al-Zaim, decided to change the name to “the Fighting Vanguard of the Muslim Brotherhood” for several considerations.

According to an analytical article published by the Malcolm Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center titled “The Syrian Brotherhood’s Armed Struggle,” the article discusses the adoption of armed struggle against the regime by the Muslim Brotherhood group.

Hadid’s efforts throughout the 1960s and early 1970s led to the growth of a group of radical extremists who wanted to push the Muslim Brotherhood into an open confrontation with the regime.

After Hadid’s arrest and death in prison in 1976, the cells he managed to train and distribute across Syria vowed to avenge his killing, starting a campaign to assassinate many top security and political figures in the regime.

Plans for targeted killings turned into a series of random jihadist attacks against Alawites, the ruling minority.

On the morning of June 16, 1979, Syria woke up to a massacre at the Artillery School in the city of Aleppo, which was carried out by the Fighting Vanguard group on a sectarian basis.

After a week of contemplation, the authorities decided to officially announce the attack, recognizing for the first time the existence of an armed opposition in the country, according to what was mentioned in the book “Syria: State of Barbarity” by the writer Michel Seurat.

Seurat added that the authorities carried out a quick retaliation in which 15 detainees accused of collaborating with the Iraqi intelligence were executed after trials that were broadcast on television. It also mobilized the religious sector by ordering some of its figures to lead “spontaneous” marches to denounce what they called the “Aleppo crime,” and waged a war of religious sermons against the “Muslim Brotherhood gang.”

The crisis reached its peak on March 8, 1980, the 17th anniversary of Baath’s rise to power. Syrian cities, except for Damascus, celebrated with strikes and chants calling for the downfall of the regime, leading to violent clashes with security forces.

After that, the ruling regime decided to resort to what it called “the revolutionary armed violence to confront the reactionary violence,” and chose the town of Jisr al-Shughour first, shelling it with helicopters to serve as a lesson for other cities.

This was followed by the invasion of Aleppo and the massacre of Tadmor Prison, which was justified as a response to an assassination attempt on Hafez al-Assad.

These practices led to a wave of Baathist repression aimed not only at destroying the Fighting Vanguard but also at weakening the Muslim Brotherhood as well, according to the article by the Malcolm Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center.

After the Muslim Brotherhood established its military branch, it was agreed in a meeting of its leadership held in December 1980 that the movement would enter into a partnership with the forces of the Fighting Vanguard organization.

This two-year relationship between the two Islamist forces provided the former Syrian president, Hafez al-Assad, with an excuse to classify the entire Islamic movement as “terrorist” and to use power and authority on an unprecedented scale.

In an article published by The New York Times by journalist Thomas Friedman, Friedman coined the term “Hama Rules” to describe the criminal act committed by the forces of Hafez al-Assad’s regime led by his brother Rifaat al-Assad and his defense minister Mustafa Tlas, which lasted for 27 days.

Friedman translated the term that summarized the policy Hafez al-Assad followed with his people as, “Rule by fear, sow fear in the hearts of your people by allowing them to know that you follow no rules at all, so they never think of rebelling against you.”

The regime’s authorities at the time justified the military invasion of the city, the complete destruction of about a third of its neighborhoods, and the massacre, by claiming that Hama was the main stronghold for the Muslim Brotherhood group in Syria.

On February 2, 1982, after campaigns of nightly raids and arrests by security elements, the army forces began a bombing campaign targeting residential neighborhoods within the city, including the destruction of 30 mosques.

Participating in the preliminary shelling were “the 47th Tank Brigade,” the “21st Mechanized Brigade” of the “3rd Division,” “Defense Companies,” along with the artillery at the military airport and Mount Zain al-Abidin.

On February 4, the regime forces committed the first mass massacre in the city, in the Southern Stadium district near the southern entrance to Hama, despite the regime’s control over this area.

On February 26, the regime’s forces stormed the city houses and took about 1,500 people to the southern outskirts of the city, where they were summarily executed by the direct order of the commander of the Defense Companies at the time, Rifaat al-Assad.

After the successive massacres, the residents were forced to participate in a pro-Hafez al-Assad march through the “March 8th Street” in the midst of the stricken city, chanting “In spirit and blood, we redeem you, O Hafez.”

The numbers of victims are disputed, while the Syrian Human Rights Committee (SHRC) has confirmed that the number of dead ranges between 30 and 40 thousand people.

if you think the article contain wrong information or you have additional details Send Correction