Muhammed Fansa | Yamen Moghrabi | Baraa Khattab

After 55 years of its establishment, the ambiguous decree scrapping of military field courts, where thousands have been sentenced to death without due process, raised many questions about the fate of the case files that were decided on the one hand and the reason for choosing this timing on the other hand, while experts and jurists underestimated the impact of this decree on improving the human rights situation in Syria.

The law that led to the establishment of these courts and concealed through them the fate of countless Syrians, as a result of the regime’s government’s secrecy of such information and the prohibition of its publication, came one year after the “setback” of June 1967, to try military personnel who deserted service or who joined the ranks of the Israeli enemy.

However, the amendment added to the law during the era of the former regime president, Hafez al-Assad, in 1980 allowed these courts to add civilians to the list of their victims.

In this file, Enab Baladi discusses the reason why the regime’s government chose this time to issue the decree in light of the interaction of the issue of detainees and forcibly disappeared persons at the international level and the political circumstances related to the Syrian file inside and outside Syria.

Enab Baladi is also trying to answer, through legal experts and human rights activists, questions about the impact of ending the field courts on the archives of adjudicated cases and the extent of their relationship to cases of enforced disappearance in Syria.

Court call or death penalty call?

“I had no hope. When they called my name at six in the morning, I felt like I was going to be executed. I could hardly believe that I was still alive,” Osama al-Zahrawi expressed the feelings that overwhelmed him when the jailer called his name to transfer him to the military field court without his knowledge.

Al-Zahrawi, 42, was tried before the field court in 2012, even though he was not a soldier, and several charges were brought against him without any concrete evidence, according to what he told Enab Baladi.

A 2021 study by the Harmoon Center for Contemporary Studies described the military field courts in Syria as having “no legal, constitutional, or international legitimacy.”

The former head of the Syrian regime, Hafez al-Assad, took advantage of the decree and amended it in 1980, to legalize field executions that targeted opponents of his rule at the time after the events in the city of Hama, and to strip the judiciary of its powers.

The amendment decree included the addition of a phrase requiring the activation of the courts “when internal disturbances occur” to the description of “war operations,” which were limited to actions carried out by the army or some of its units in war or when an armed clash occurred with the enemy, affecting civilians.

Since the outbreak of the Syrian revolution in 2011, these courts have returned to the forefront, and many opponents of the regime have been transferred to them on charges mostly related to “terrorism,” according to the Harmoon Center’s research.

The torture journey for the detainee begins from the moment of his arrest, as he is subjected to severe beatings from the moment of his arrest, and this continues during the road trip to the security branch, where a “reception party” of beatings and insults from all the officers present awaits him, according to al-Zahrawi.

The features of the field court trip do not differ much from the torture trip during detention, as the detainee is subjected to various types of beatings and humiliation while being taken to the field court.

Al-Zahrawi recounted the details of his ambiguous trip to the field court, saying, “They called our names at six o’clock in the morning, then they tied my hands behind my back and blindfolded me with a cloth. We did not know where they were taking us. We felt that we were going to be executed due to lack of hope, and we had no choice but to die.”

At the court’s venue, each person is called by name to enter alone with one of the soldiers, according to al-Zahrawi, who recalled these moments, saying, “I still remember that scene as I entered the court, where the judge asked the attendant to remove the cloth from my eyes, and the first person I saw in front of me was Major-General Mohammad Kanjo and next to him was the Attorney General.”

The Attorney General began to file some charges against the young man, centering around his role in the Qaboun Revolutionary Coordination Committee, causing the death of members of the regime, and other charges that al-Zahrawi denied, adding that he confessed to everything he said under pressure and torture.

“My trial did not exceed four minutes, and several people were with me. They announced our names in succession and took us away without a lawyer or even without us knowing the ruling,” al-Zahrawi added.

The ruling was not issued immediately, and al-Zahrawi remained in prison for six months, after which he was transferred to the Damascus Central Prison, better known as Adra Prison, where he remained for about two years and seven months until a seven-year prison sentence was issued, stripping him of his civil and military rights.

Bashar al-Assad with army forces in regime-held areas in the northwestern Idlib region – October 2019 (SANA)

Perfunctory Trials

“The trial did not last three minutes, and I got out of it by beatings without knowing my fate, even a month before I was released from prison, while I was stripped of all my civil and military rights, and my property was seized.” Mohammad summarizes to Enab Baladi the proceedings of the field court and what resulted from it.

Mohammad, a pseudonym for a young civilian who refused to publish his real name for security reasons, was subjected to a field trial after he was arrested by the Air Force Intelligence Branch and stayed in the notorious Sednaya Prison for six months before the trial.

In the trial, according to what he told Enab Baladi, Mohammad faced charges of incitement and carrying out terrorist operations.

But the young man tried to explain to the judge that these charges were extracted under torture, and he tried to take off his shirt to show him signs of torture, but he was met with beatings from the accompanying officer, who took him out immediately, according to the young man’s account to Enab Baladi.

After 2011, 70% of the detainees in Sednaya Prison alone were transferred to military field courts, which sentenced most of them to death, and they are run by military personnel who do not have a law degree, according to Diab Sariya, the co-founder and director of the Association of Detainees and The Missing in Sednaya Prison (ADMSP).

On December 23, 2018, The Washington Post revealed that the number of detainees in Sednaya Prison was declining “very rapidly” due to executions after field trials inside the military prison.

The veteran newspaper relied on satellite images, showing the presence of dozens of shadowed objects that turned out after analysis to be the bodies of executed detainees, in addition to photos taken near Damascus, showing an increase in the number of graves and excavations.

In 2017, Amnesty International published a report on field executions in Syria and quoted a former guard at Sednaya Prison, saying that more than 13,000 detainees were executed by hanging in the prison between 2011 and 2015 after a “quick field court.”

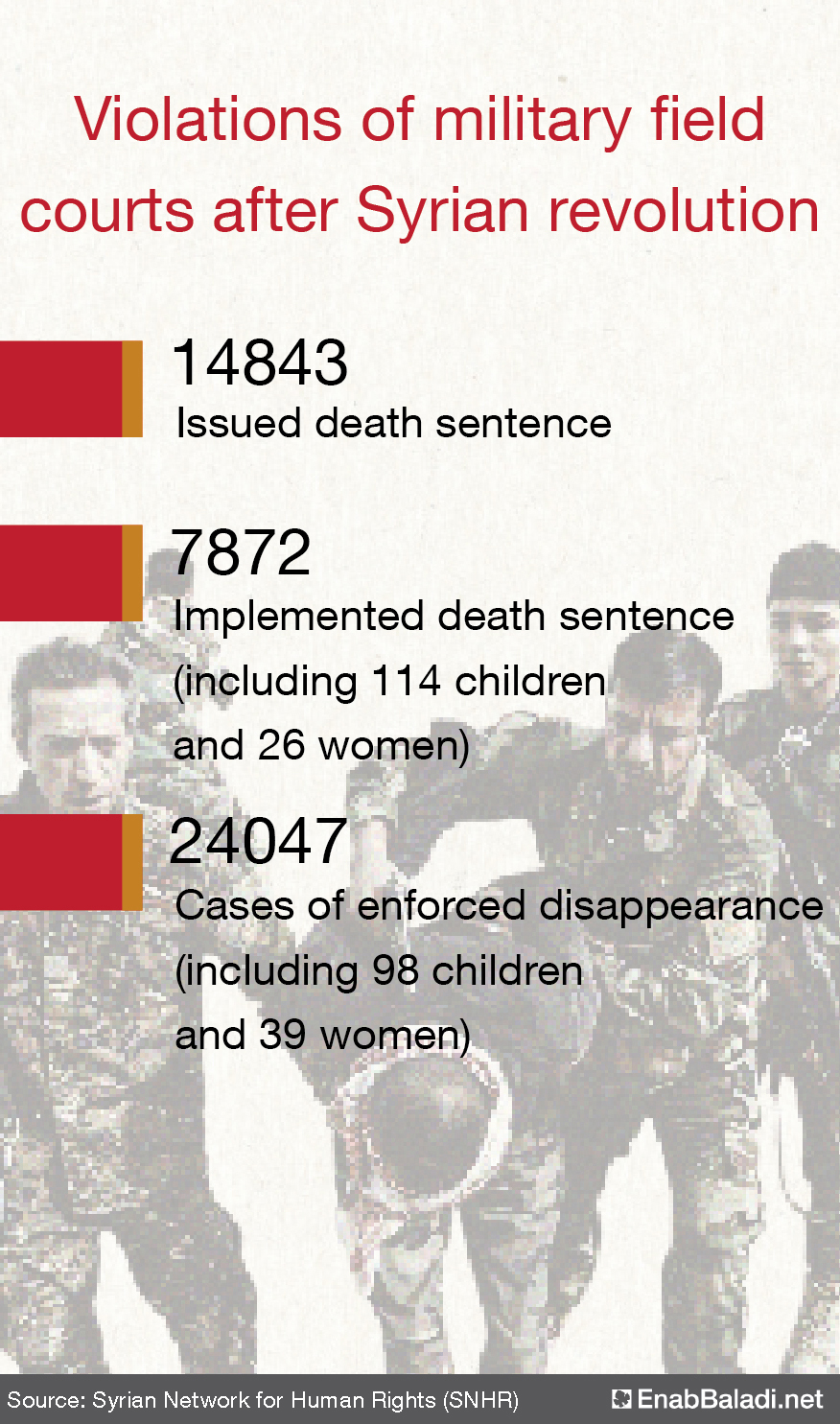

The regime used these courts “as a tool of killing and concealment against activists and opponents,” according to the description of the Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR) report issued on September 12, which documented the field courts issuing 14,843 death sentences, of which no less than 7,872 were executed, and among those sentenced were 114 children and 26 women.

The regime’s game, political exploitation of every step

Al-Assad issued the decree that ended the field courts, coinciding with the interaction of the Syrian file at the internal and external levels.

Internally, protests in the city of As-Suwayda in southern Syria continue, demanding al-Assad’s departure, the overthrow of the regime, and the implementation of UN Resolution 2254 (2015), which stipulates the formation of a transitional governing body and elections under the supervision of the United Nations. A state of tension is emerging in other regime-controlled areas as a result of the economic crisis and the stagnation of the political file.

Externally, the decree is linked, according to analysts, to the Arab Initiative or what was known as the Jordanian Initiative and the principle of a “step-for-step.”

The Jordanian Initiative obtained by Al Majalla magazine on June 25, reveals that Amman, along with Arab capitals that directly support it and Western capitals that tacitly endorse it, still consider the withdrawal of Iran from Syria as their ultimate goal in exchange for lifting sanctions, rebuilding Syria, and the withdrawal of the United States.

Therefore, the decree can be read as a step, even if formalistic, implemented by the Syrian regime in this context to send a message to the Arab countries that returned it to occupy Syria’s seat in the Arab League and to Western countries about the possibility of changing its behavior, especially with the increasing prosecutions by Western countries of those involved in torturing Syrians and carrying out violations against them in detention centers, and the United Nations’ formation of a special institution to search for missing persons in Syria.

Regime’s message to International Community and Arabs

After the earthquake disaster that struck southern Turkey and northern Syria last February, the movements of Arab countries towards the Syrian regime increased, and they presented to it the Arab Initiative within the principle of a “step-for-step.”

The initiative touched on the file of political detainees and addressed a mechanism to address the file in the near term through the regime providing detailed information to United Nations offices about the beneficiaries of the presidential amnesty issued in April 2022.

In addition to releasing arbitrary detainees, agreeing to release detainees gradually and cooperating with the Red Cross to determine the locations and fate of missing and kidnapped persons.

The third phase of the initiative talked about “expected steps from Damascus,” including reforms to ensure good government and prevent persecution.

Mounir al-Fakir, a fellow at the Omran Center for Strategic Studies, said that the decree’s connection to the Arab Initiative and the regime’s movements in this file is greater than its connection to the As-Suwayda protests, and it attempts to delude the Arab countries that it creates the appropriate legal and human rights environment for the return of refugees without accountability and the expression of their opinion.

Based on this matter, the regime offers a formalistic “concession” as a step in return for a step from the Arab countries, in accordance with the principle of the initiative.

Therefore, it is necessary for the media and research centers to refute the decree and the reasons for its issuance, given that countries and governments take these matters in their formalities and not in their real content sometimes, according to al-Fakir.

Lawyer and human rights activist Mahmoud Hamam told Enab Baladi that the Syrian regime is trying, through the decree, to blackmail the international community and say that it is trying to change its behavior and local laws to obtain greater gains in light of the political and economic conditions it is going through.

The Syrian regime will try to exploit the decree during the coming period, locally and internationally, to portray the matter as a transition to a new level in terms of developing the tools of governance and political and security reform (formally) and to market the matter, even at the level of the Caesar Act file, as alleviating the severity of the violations that the Syrians face, which field courts are one of its tools, al-Fakir said.

Prisoners in Damascus Central Prison (Adra) released under a presidential amnesty decree – 2014 (AP)

Field courts, the “black hole” of enforced disappearance

The file of forced disappearance is one of the most important files in Syria, and it relates to thousands of Syrian families, with thousands of people forcibly disappeared by the various authorities controlling the land in Syria, the largest number by the Syrian regime, according to the Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR).

The network’s report, issued on September 12, stated that the military field courts are considered one of the worst forms of exceptional criminal courts established in the history of Syria for several reasons, including that they are considered one of the main organs of the Syrian regime that is responsible for the crime of enforced disappearance.

The numbers mentioned by the network in its report demonstrate the extent of the role played by these field courts in the process of forced disappearance of thousands of Syrians whose fate is unknown, in a systematic manner based on thoughtful decisions and directives issued in accordance with a security and military system with an interconnected organizational structure starting with the President of the Republic.

Mohammad al-Abdallah, Director of Syria Justice and Accountability Center (SJAC), described to Enab Baladi the field courts as one of the tools of enforced disappearance in Syria and added a legal character to the arrests carried out by the security services, with detainees being subjected to quick field trials in the Tadmur (Palmyra) and Sednaya prisons and al-Qaboun, without the presence of lawyers or opportunity to appeal, and in the absence of the most basic standards of fair trials.

Human rights activist Hamam described to Enab Baladi these courts as a “black hole” for forced disappearance in Syria.

Those who are tried through it are subject to disappearance from the world, and their fate becomes unknown, especially since the decisions of these courts are security decisions that prohibit revealing the numbers of those convicted or their fates, and death sentences are carried out without issuing death certificates or informing the families of the deceased, according to Hamam.

What happens to the records of convicted prisoners? Experts answer

Mystery has surrounded the fate of the records and files of cases decided by the field courts since their formation 55 years ago, in light of the fact that the decree to end the courts did not specify the fate of these documents.

One of the most prominent concerns raised by the decree is related to erasing thousands of crimes committed against Syrians, especially in the absence of any guarantees for the process of transferring the archives of these courts to civilian or even military courts.

Consequently, perpetrators of violations related to death sentences, enforced disappearances, and unfair trials in Syria are not guaranteed to be held accountable.

Al-Abdallah of the SJAC told Enab Baladi that it is difficult to obscure these crimes committed, especially since the number of people executed because of them is very large, and the decree does not absolve the head of the Syrian regime, Bashar al-Assad, from any responsibility for them.

The abolition of field military courts does not negate criminal responsibility for what happened there after 2011, and the death sentences issued against Syrians, which are summary sentences that are considered a crime, just like torture, even if they were issued by judicial rulings because the court is not recognized in the first place.

For his part, lawyer Hamam said that the decree has no impact on the possibility of holding the Syrian regime accountable despite the presence of hundreds of witnesses, documents, and documentation carried out by Syrian human rights organizations.

According to a study by Omran Center for Strategic Studies issued on September 14, abolishing the field courts eliminates al-Assad’s need to ratify the death sentences issued by it, and thus, he can evade his direct responsibility for the executions carried out by these courts after it was greatly activated since 2011.

All the security services affiliated with the Syrian regime referred most of their detainees to the Military Field Court, and referrals to it later increased to deal with all cases related to the peaceful and armed movement, according to the study.

It is expected that these agencies will begin referring their detainees to the military judicial courts, the terrorism court, or the civil judiciary, while the assessment and description of the “crime” will remain subject to the security services, according to the study, which also indicated the absence of judicial independence, whether in the military or civil judiciary.

|

The field courts are one of the black spots in Syria’s history, and there are thousands of Syrians executed by the military field courts. Mohammad Al-Abdallah, Director of Syria Justice and Accountability Center |

Joumana Seif, a legal advisor in the International Crimes and Accountability program at the European Centre for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR), told Enab Baladi that, in theory, after canceling this decree and transferring jurisdiction to the military judiciary, all archives and records should be transferred to it.

Given the criminal history of the Syrian regime in the human rights file, Seif doubted that the regime would allow the families of the victims to access and review these records to know the fate of their loved ones or relatives who were tried in the field courts.

In her interview with Enab Baladi, Seif referred to the amnesty decrees issued by the regime without revealing the records of those pardoned or dealing transparently with the numbers who were released according to these decrees.

Meanwhile, the legal official in the Syrian Legal Development Program (SLDP), lawyer Mouhanad Sharabati, believes that determining the fate of the Field Court’s records through this decree raises a major problem.

Sharabati believes that the regime’s intention, through the decree, is to destroy these records and thus to lose all evidence and documents about the people who were tried and executed by this court.

The Legal Office at the Syrian Center for Media and Freedom of Expression told Enab Baladi that the decree comes in the context of the regime’s attempts to obscure the facts and hide its responsibility for the part of the crimes of enforced disappearance and summary execution related to the field courts.

The legal office based this opinion on the fact that the text of the decree referred only the cases currently pending and in their present condition before the field courts to the military judiciary, without clarifying the fate of the former convicts or referring to the files and previous rulings issued by them, which indicates an attempt to evade criminal responsibility by canceling the court and destroying all related files and records.

The Syrian regime is awaiting an international hearing through a hearing in the International Court of Justice (ICJ) regarding the case filed against it regarding torture in prisons on the 10th and 11th of next October, after it was postponed from July 19, according to the court’s decision based on a request from the Syrian regime’s government.

Attention is also turning to the international body established by the United Nations last June to clarify the fate of missing persons in Syria.

The new body requests the UN Secretary-General to establish the terms of reference of the independent institution within 80 working days of the decision being taken, with the support of the UN Human Rights Office and in consultation with all relevant actors, including the full and meaningful participation of victims, survivors, and families.

It also requests the Secretary-General to report on the implementation of this resolution within 100 working days of its adoption and to submit annually a report on the activities of the independent institution.

The Syrian regime is most responsible for the number of missing and forcibly disappeared people in Syria out of the total number of parties to the conflict, according to SNHR data.

Cells and prison rooms inside Branch 215 in the Kafr Sousa neighborhood in Damascus city – (Syrian Observatory for Human Rights)

Difference between field courts and military judiciary

The decree ending the military field courts referred all cases in their present state to the military courts for prosecution, which in turn moved away from the jurisdiction of their name and began trying civilians.

According to lawyer Sharabati, the jurisdiction of the Military Judicial Court was expanded, and it was given the authority to look into many crimes under special laws enacted over a period of several years, even if the perpetrator of the crime was a civilian and there were no military personnel in the case.

Lawyer Joumana Seif described the military field courts as “very notorious” courts because they are secret and do not meet the conditions for a fair trial, even at the minimum, such as appointing a lawyer or appealing their decisions.

While the military judiciary has two aspects, the first is that it is specialized in everything related to the army institution and military punishments, such as possession of weapons and others, and an “exceptional” aspect in light of the state of emergency.

Crimes against public authority are referred to the military court, such as crimes against employees, including defamation and slander against the President of the Republic, or the destruction of official papers, according to Seif.

Among the courts that lawyer Joumana Seif witnessed was the trial of writer Ali al-Abdallah in the military judiciary in 2010 because he wrote an article about Iranian hegemony and influence.

Lawyer Ahmed Sawan explained that the military judiciary is competent to apply the Military Penal Code, which includes the principles of trials before this judiciary, noting that there are “reasonable limits” to the right of defense through the role of the lawyer to attend trials and present defenses and appeals.

As for the military field courts, they deprive defendants of the assistance of a lawyer, and lawyers are not given any right to view case files.

Also, when issuing its rulings, the field court relies on confessions extracted under torture, according to what Sawan told Enab Baladi.

Sharabati pointed to a “problem” related to the Public Prosecution in the Field Court, which has broad powers that include the powers granted to the Attorney General and the Military Investigative Judge.

The rulings issued by it are final and do not accept any form of appeal according to Article “4” of Decree “109” of 1968, and therefore, those with cases that will be referred to the military judiciary lose their right to appeal the prosecution’s decisions.

|

The Syrian regime used the military judiciary to bring charges against civilian political opponents who were deemed to have committed crimes against state security or public safety, undermining the state’s prestige or national sentiment, or inciting sectarian strife, among other charges. Joumana Seif, Syrian lawyer and legal advisor in the International Crimes and Accountability program at the European Centre for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR) |

Legally, what is the difference between military field courts and the military court?

Military field courts were established in 1968. They are competent to examine crimes within the jurisdiction of military courts, referred to them by a decision of the Commander-in-Chief of the Army and Armed Forces, and committed during times of war and military operations.

The court shall be formed by the decision of the Minister of Defence and shall consist of a president and two military members. The rank of the president shall not be less than a major, and the rank of each of the two members shall not be less than a captain.

The field court may not abide by the principles and procedures stipulated in the legislation in force, and its rulings are “final” that are not subject to appeal, and are subject only to ratification by the President of the State in the event of a death sentence, and by the Minister of Defense in the case of other rulings.

As for the Military Judicial Court, it is a permanent court based in Damascus. Its formation and jurisdiction are determined by the Military Penal Code and Procedures issued by Decree No. 61 of 1950.

The military court consists of three judges, one of whom is a military judge. Military courts are subject to the supervision of an executive authority affiliated with the Ministry of Defense, and judges are appointed by decree based on the proposal of the Commander-in-Chief of the Army and Armed Forces.

Military courts can decide cases in which one party is a military man, even if the other party is a civilian.

A woman looks sadly at pictures of Syrians in the Caesar Exhibition of Torture Victims inside the United Nations Headquarters – September 2015 (Internet)

What are the powers of the Military Court?

- Crimes committed in military camps, institutions, and places occupied by military personnel for the benefit of the army and armed forces.

- Crimes committed against the interests of the army.

- Crimes committed by men of allied armies residing in Syrian territory, and all crimes affecting the interests of these armies, unless there are special agreements between their governments and the Syrian government that contradict these provisions.

- Crimes committed through printed writings of all kinds, such as insulting the flag or the army or harming its dignity or reputation.

After expanding the court’s powers according to separate laws, the most prominent of them included:

– Violating orders issued by the martial law ruler, such as firing gunshots on special occasions.

– Possession of military weapons without a license.

– Crimes against public authority from Article “369” to “387” of the Syrian Penal Code, such as:

– Insulting or slandering the head of state, public administrations, regulatory bodies, the army, or an employee because of his position.

– Impersonating a person or position.

– Practicing a profession subject to a legal system without the right.

– Breaking the seals placed by the authority.

– Destruction of official papers and documents.

– Crimes against state security and public safety.

– Illegal connections with the enemy.

– Undermining the state’s prestige and national feeling.

– Membership in a political or social association of an international nature without government permission.

– Inciting sectarian and racist tensions and violating civil rights and duties.

– Belonging to secret societies, demonstrations, and riot gatherings.

– Publicly insulting a foreign country, its army, its flag, or its national emblem.

– Violating the safety of roads and transportation.

Additional “repressive tool” is in place

The demand to abolish the notorious Field Court is an old demand of lawyers, dating back 45 years. The General Conference of the Syrian Lawyers Association held a conference in 1978 to discuss the status of freedoms, the rule of law, and the judicial system.

The demand concluded with several recommendations, including the abolition of field courts, even though they did not try civilians at the time in accordance with the amendment that occurred two years later.

After the abolition of the Field (al-Maidan) Court, what remains is to abolish the Terrorism Court, empower the judiciary, provide a climate of freedom and the rule of law, and release detainees without judicial warrants, according to the opinion of the lawyer residing in Syria, Aref al-Shaal.

With the start of the Syrian revolution in 2011 and the demonstrations that called for the overthrow of the regime, al-Assad tried to issue new laws to circumvent the demands of the street. He abolished the emergency law and Article 8 of the constitution, which stipulates that the Baath Party is the leader of the state and society, and also abolished the State Security Court. But al-Assad created an alternative to it, the Terrorism Court.

The Terrorism Court was established in July 2012 and issues its decisions in accordance with the Anti-Terrorism Law issued in the same month.

Lawyer Ahmed Sawan does not expect the regime to respond to the demands to abolish this court, explaining its adherence to this court as a “repressive tool” that allows it to violate the rights of those opposed to al-Assad’s “tyrannical rule.”

The Terrorism Court does not adhere to the principles of trial in all the roles and procedures of prosecution and trial and commits many violations against the Syrians who are tried before it.

Among them is depriving the accused of the right to defend and appoint a lawyer, despite the presence of this right in the law establishing it, but the facts confirm that the accused are deprived of the assistance of a lawyer, according to Sawan.

This court relies on confessions extracted under torture as a basis for sentencing the accused, and it relies on arrests organized by security personnel.

The Terrorism Court tries civilians, military personnel, and juveniles alike, which contradicts the rules of specific jurisdiction, and the President of the Republic, according to the Court’s law, is the one who appoints judges in violation of the standards of the principle of separation of powers.

Syrian lawyer and legal expert Joumana Seif believes that the abolition of the Terrorism Court depends on achieving a transition and democratic rule in Syria, based on the fact that the regime is based on “intimidation and violence” using tools such as this court.

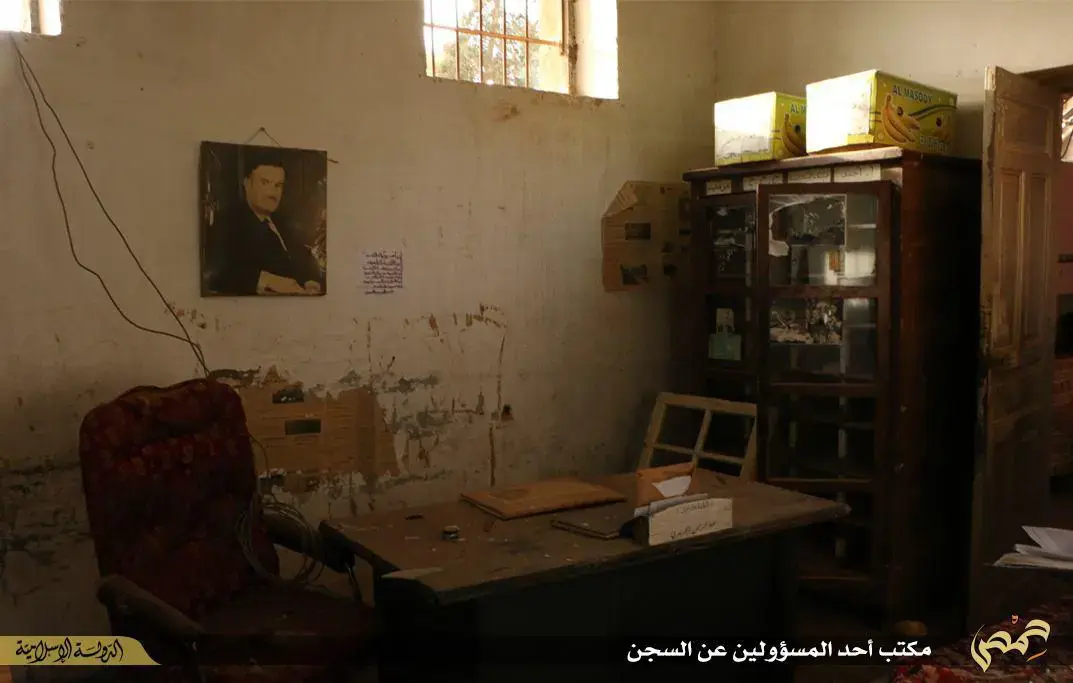

A picture of the office of an official in Tadmur (Palmyra) Prison, which witnessed the implementation of field trials for detainees before it was blown up by the Islamic State group in 2015 (Amaq Agency)

What can human rights organizations do after scrapping field courts?

Al-Assad’s decree relates practically to two files that are extremely important to Syrians: the file of detainees in the Syrian regime’s prisons and the file of the forcibly disappeared, and these are two files that Syrian and international human rights organizations are working on.

The recent decree abolishing the field courts can be exploited by these organizations and put pressure on the Syrian regime.

Al-Abdallah, director of Syria Justice and Accountability Center, said that the first thing that human rights organizations can do during the next stage is to continue documentation and monitor the military court and the military judiciary, to ascertain how the cases proceed after they are referred from the canceled field court to other courts.

It is necessary to know the condition of the detainees whose files will be transferred to other courts, and thus, it will be possible for the families of the detainees to obtain the ruling document from the court and to know the fate of thousands of missing persons.

Therefore, human rights organizations’ monitoring of what will happen in the military judiciary will be an essential factor in the coming period, according to al-Abdallah.

The Legal Office at the Syrian Center for Media and Freedom of Expression believes that civil society organizations must always emphasize and demand that court records be disclosed and made available to the public to enable Syrians to exercise their right to know the truth and to enable families to know the fate of their children.

The Legal Office also called for emphasizing the criminal responsibility of the court’s judges, the Commander-in-Chief of the Army and the Armed Forces, and the Ministers of Defense and considering them as suspects of war crimes and crimes against humanity who must be tried.

if you think the article contain wrong information or you have additional details Send Correction

النسخة العربية من المقال

-

Follow us :

Syrian regime President Bashar al-Assad scraps notorious military field courts that carried out thousands of executions against the Syrian people (Edited by Enab Baladi)

Syrian regime President Bashar al-Assad scraps notorious military field courts that carried out thousands of executions against the Syrian people (Edited by Enab Baladi)

A

A

A

A

A

A

More In-Depth

More In-Depth