Enab Baladi – Lujain Mourad

Demands are renewed for the opening of United Nations offices in northwestern Syria with every crisis or disaster affecting the region, especially after the delay in responding to the earthquake disaster, as the United Nations relies on its offices in Turkey to coordinate its relief work in northern Syria.

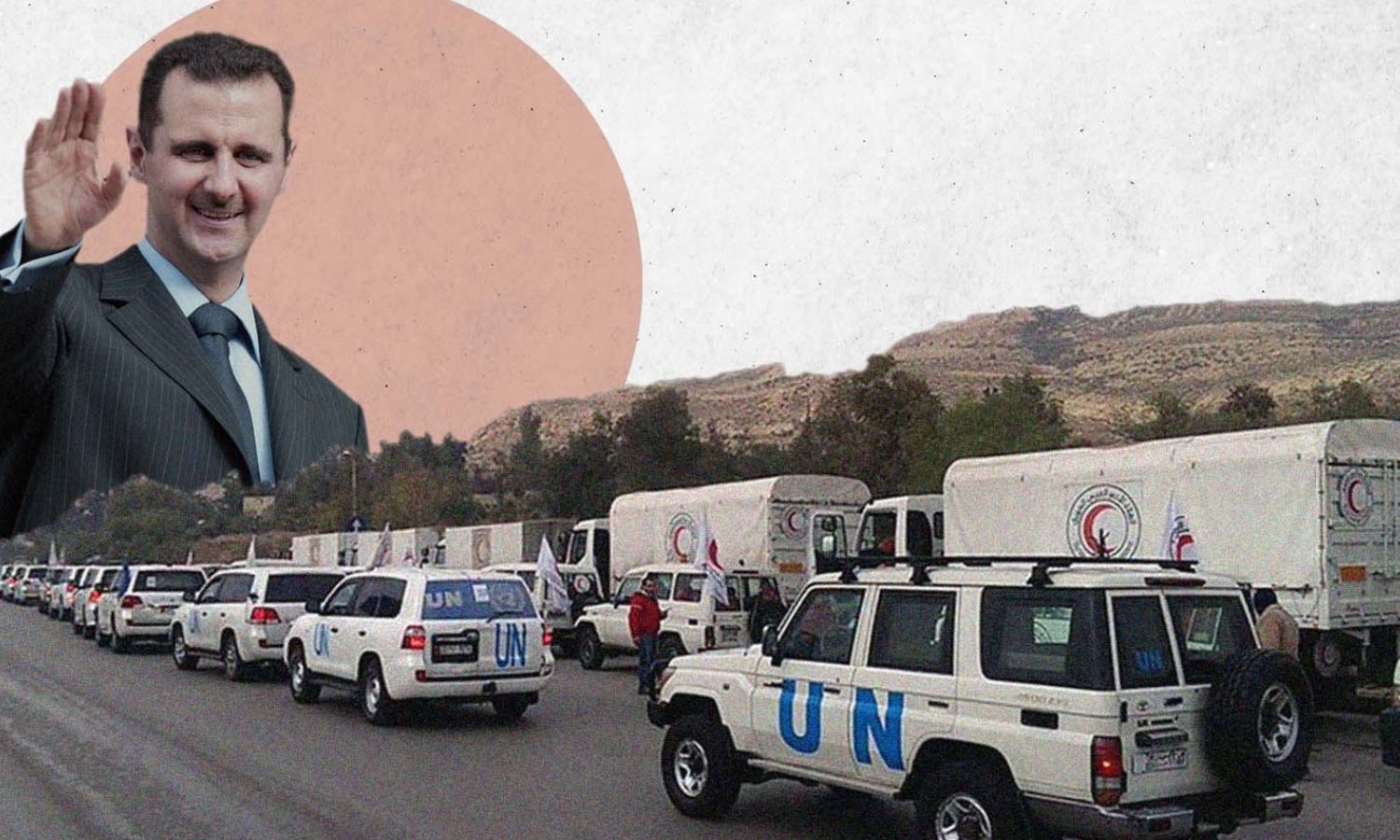

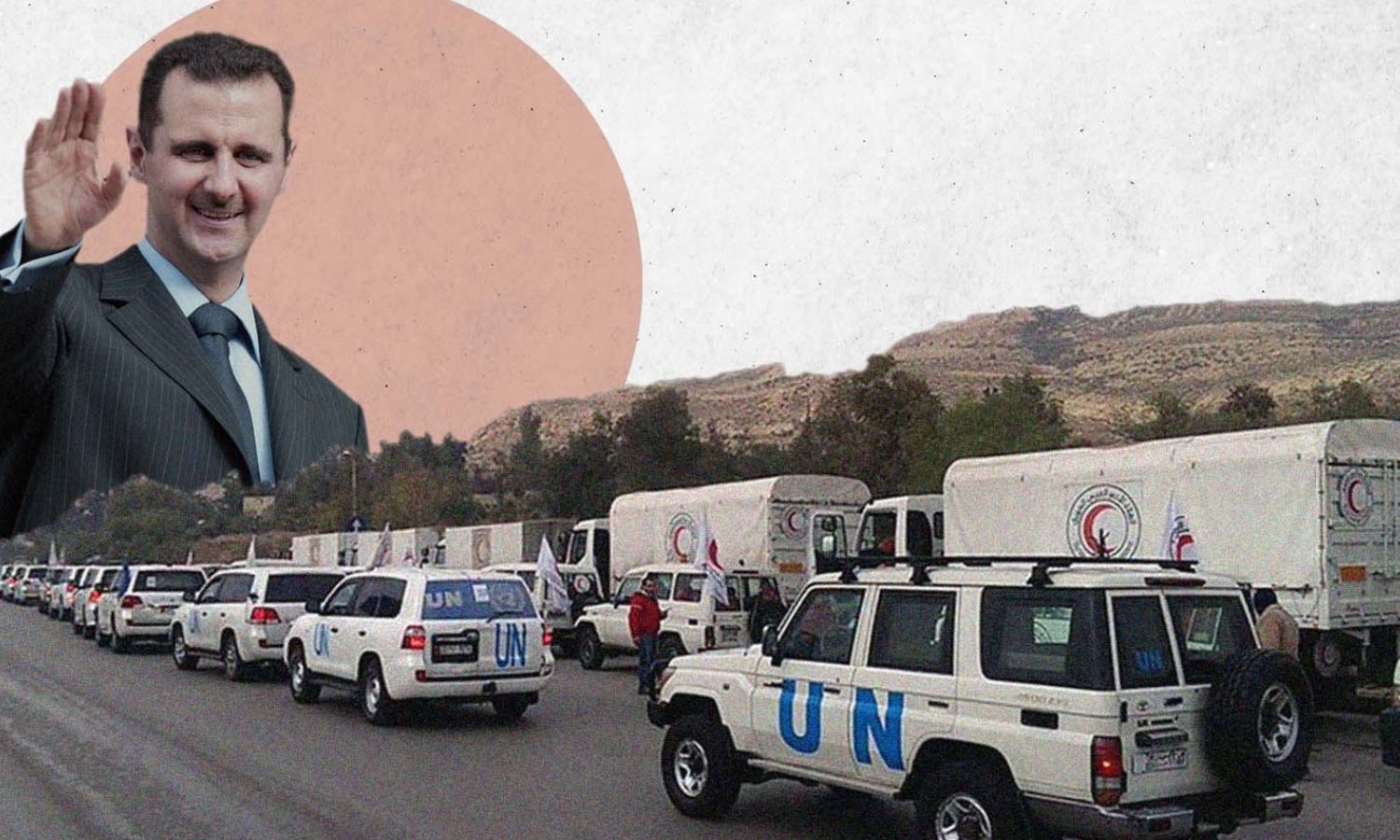

The demands came days after the February 6 earthquake and a meeting between the UN Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs, Martin Griffiths, and the head of the Syrian regime, Bashar al-Assad. The UN notified the Syrian organizations operating in the north of the existence of a decision to open UN offices without an official announcement.

The decision raised many questions and concerns about its causes, timing, and its relationship to the delay in response to the earthquake disaster. During the past years, the United Nations relied on its offices in the Turkish Gaziantep city to coordinate its work in northern Syria, especially regarding cross-border aid, according to what workers in the organizations told Enab Baladi.

This coincided with the continuing talk about the delay of the UN response to the earthquake disaster, which many humanitarian workers attributed to the lack of official UN offices and representation in northern Syria.

The Executive Director of the Bousla Development and Innovation Organization, Hassan Junaidi, told Enab Baladi that the first notification to the Syrian organizations came from the Deputy Regional Coordinator for Humanitarian Affairs, David Carden.

This was followed by a special meeting, attended by Junaidi, on the operational principles of the offices’ existence, during which organizations asked many questions about the steps that preceded the move to open the offices, but they did not receive a response, according to what Junaidi told Enab Baladi.

For his part, the humanitarian activist and advocate, Dr. Mohamad Katoub, criticized, during an interview with Enab Baladi, the United Nations’ behavior and its reticence to answer the organizations’ questions, pointing out that it was content with reporting, and did not show any intention to consult with them and answer their questions.

Enab Baladi forwarded questions to the United Nations Deputy Spokesperson, Farhan Aziz Haq, via e-mail, about the details of the plan to open offices in northern Syria and its relationship to the UN office in Damascus, in addition to the timing of the decision, but he did not provide clear answers on the matter.

Aziz Haq’s answer was limited to saying, “The United Nations is present in various regions of Syria, but it needs cooperation from the central government in Damascus and the de facto authorities to achieve its endeavors to meet humanitarian needs.”

Enab Baladi contacted an employee of the United Nations offices in Gaziantep (who refused to reveal his name because he is not authorized to speak to the media). He said that so far, there is no text of an official decision to open offices, but UN employees have begun working on proposing and evaluating locations for offices.

He added that it takes a long time and many approvals, pointing out that the rumors about the offices starting their work officially soon are not true.

The United Nations was not satisfied with notifying the organizations alone, as it informed the Syrian Interim Government (SIG) of its plan, according to what the Minister of Economy of the Interim Government, Abdul-Hakim al-Masri, said, who repeatedly appeared alongside the UN delegations in northern Syria after the earthquake disaster, stressing that there was no official notification of that.

The local organizations’ questions focus on the role of the offices in the event of their opening and the chance of coordination between those offices and the United Nations offices in Damascus, in addition to what lies behind the timing of the decision, according to Katoub.

Although the presence of UN offices has been a requirement for organizations for years, the decision raised many concerns, which were reinforced by the absence of answers to the organizations’ questions, the former aid worker added.

Katoub welcomed the move to open offices, in case it was linked to the growing need after the earthquake, but if it was to cover the failure of the United Nations during the disaster and subject to al-Assad’s approval, it is considered a “negative curve.”

The Executive Director of the Bousla Development and Innovation Organization in the Syrian Forum, Hassan Junaidi, agrees with what Katoub mentioned, as he said that the presence of offices provides a better mechanism for the process of documenting violations and coordinating aid, but the way the United Nations coordinated with the organizations’ cadres and the method of notifying them was sufficient to create great concerns for the organizations of the consequences of having offices.

|

We are not saying that we support or reject the idea. What we simply say, as Syrian institutions, is that we need more clarity and understanding of the process of establishing UN offices in northern Syria. Hassan Junaidi, executive director of Bousla Organization |

Junaidi added that the existence of possible coordination between the United Nations offices in Damascus and the offices of the north in the future means the exchange of beneficiaries’ data, which raises great concerns among local organizations.

Yasser Tabbara, Ph.D. in Law and member of the Board of Directors of the Syrian Forum, told Enab Baladi that the most prominent problem with this file is related to the legality of the presence of these offices in northern Syria.

The UN usually operates in areas controlled by central governments, which makes its presence in areas outside the control of the government of the Syrian regime linked to a mandate from the Security Council or the approval of that government.

Considering that the decision to open the offices is linked to al-Assad’s meeting with the United Nations aid coordinator, Martin Griffiths, the organizations fear the decision’s relationship to the approval of the Syrian regime, Tabbara said.

Coordination regarding the arrival of cross-border aid is carried out through the United Nations office in Gaziantep, away from the possibility of the Syrian regime tampering with it, which has made renewing the cross-border aid decision a constant demand for Syrians and local and international organizations.

Dr. Tabbara believes that if the legal basis for the presence of offices in the north is subject to the approval of the central government in Damascus, then this necessarily means that the coordination of the work of these offices will take place in cooperation with the Damascus offices.

The coordination between the offices of the North and Damascus entails increasing the focus on cross-line aid (from the areas controlled by the Syrian regime to northwestern Syria) at the expense of cross-border aid, according to Tabbara, pointing out his fear that this might lead to a complete halt to cross-border aid.

|

This presence could be a step to end cross-border aid through increased coordination between the United Nations and Damascus so that all humanitarian aid is at the mercy (control) of al-Assad. Hassan Junaidi, executive director of Bousla Organization |

Several UN delegations visited northern Syria days after the earthquake disaster, coinciding with many meetings and visits to Damascus, which resulted in the Syrian regime agreeing to deliver aid to northwestern Syria through two additional border crossings with Turkey for three months, according to UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres on February 13.

Commenting on this, the Syrian regime’s representative to the United Nations, Bassam al-Sabbagh, said that the decision to open the two additional crossings within the Security Council is not required, pointing to the existence of “an agreement between Syria and the United Nations.”

This also coincided with the emergence of indications of an “undeclared political deal with UN participation,” its features emerged through “concessions” made after the intransigence of both the Syrian regime and the United States for years, according to what experts said in a previous interview with Enab Baladi.

The mandate of the Security Council resolution to deliver foodstuffs, medicine, and other basic aid through the Bab al-Hawa border crossing from Turkey to northwestern Syria for a period of six months will expire next July, amid continued Russian pressure to freeze the resolution in return for relying on cross-line aid.

if you think the article contain wrong information or you have additional details Send Correction