Jana al-Issa | Hassan Ibrahim | Lujain Mourad

United Nations and international response plans have failed to resolve the worsening Syrian refugee education crisis in Lebanon over the years, marking a failure added to the record of numerous failures that affected Syrian displaced persons and refugees inside and outside the country.

The Lebanese suffer from several living, economic, and political crises affecting the country. Syrian refugee children have had the “greatest” share of the resulting negative effects. Racial discrimination and the government authorities’ treatment and decisions regarding their educational situation have driven the proportion of children dropping out of school to increase and reach unprecedented figures.

In this file, Enab Baladi discusses the crisis of the educational process for Syrian refugees in Lebanese public and private schools and the authorities’ handling of it, in addition to the role of international organizations in alleviating their burden. It also discusses with experts possible proposals to improve the reality of education and the extent to which they can be achieved under the current circumstances.

Public education

Syrians are denied “integration”

“Both of my eldest sons have been deprived of education. We are all trying to make it possible for children to complete their education.” In these words, Syrian refugee resident in Lebanon, Adib al-Qaq, expressed his conviction in the importance of his two young children pursuing their education, “whatever the cost,” as he said.

After taking refuge in Lebanon in 2013, al-Qaq was able to enroll his four children in a private school, but for a temporary period, as the family’s loss of everything they owned in Syria and the high costs of enrolling in private schools forced him to search for an alternative. The poor living situation prompted the young man later to withdraw his two eldest sons from school to search for a job opportunity that would enable them to help the family financially.

Despite his repeated attempts, al-Qaq did not find a place for his two young children, Ghina and Abdul-Hakim, in the nearby primary schools where he lives in Mount Lebanon governorate. Those schools closed their doors to the Syrians and prevented them from attending morning classes, nor did they accept adding evening classes for them.

Al-Qaq enrolled his children in a school about seven kilometers away from their home, explaining that he uses the monthly salary of his eldest working son, no more than 3.5 million Lebanese pounds (about 100 dollars), to pump gasoline and drive his two children to the said school.

Dozens of parents wait daily in front of the school in search of an opportunity to enroll their children, according to what al-Qaq told Enab Baladi, citing the suffering of Syrian refugees while their children are deprived of education due to the limited numbers that Lebanese schools allow in relation to evening classes reserved for Syrians.

“Education in Emergencies”

Lebanon relies on the Education in Humanitarian Crisis (EiC) model, commonly known as “Education in Emergencies,” which is the most widely adopted model in thinking and planning for the education of refugee children who are temporarily living in host countries awaiting repatriation.

According to a study issued by the Center for Lebanese Studies, the Lebanese authorities have confirmed on more than one occasion their adoption of this model.

Lebanon views refugees from Syria as displaced; hence this method of humanitarian and relief work is distinguished by dealing with educating refugees by using short-term policies and programs and avoiding using policies that aim at long-term social, economic, or educational integration.

The Lebanese Ministry of Education and Higher Education separated Syrian students from their Lebanese peers in school by introducing the evening education system, which played a major role in reinforcing racist ideas and imposing greater difficulties on Syrian students trying to integrate into countries of asylum.

This system also deprived many students of education, as most Syrians prefer to enroll their children in the morning shift, considering the teachers in the evening shift as “contractors,” that is, they do not possess educational skills.

The evening teaching shift extends for four hours, from two in the afternoon until six in the evening, without rest times for students, which weakens the quality of education and the ability of students to receive information.

According to the Lebanese Studies Center, many students were forced to return home late due to the long distance between the school and their families’ places of residence, with the lack of transportation.

Although international organizations and civil bodies sought to integrate Syrian students into Lebanese schools and to abolish the “discriminatory restrictions” that impede Syrian students’ access to education by making integration a condition for support, the Lebanese authorities rejected the matter and did not respond to the UN demands.

Before the start of the current academic year, Abbas al-Halabi, the Lebanese Caretaker Minister of Education and Higher Education denied the possibility of integrating Syrian students into formal education before noon after speaking to several unofficial sources, considering that the matter “is not proposed, and is nothing but a conspiracy against formal education, for not encouraging parents to enroll their children in public schools.”

Adib al-Qaq, Syrian refugee in Lebanon, went to his two children’s school a short time ago during the morning shift for Lebanese students, but he was abused by one of the teachers who “refused a Syrian entry to the school during the Lebanese children’s shift,” he told Enab Baladi.

Additional obstacles

The Lebanese Ministry of Education also impeded the entry of Syrian students into schools by preventing students from taking school exams without submitting official papers.

This forced many Syrian families to pay more than they could afford and return to Syria in dangerous conditions to obtain official documents, Human Rights Watch (HRW) reported in 2021.

Al-Qaq said that many schools, including the school of his two children, did not set official papers as a condition for admission this year, unlike in previous years.

Last March, a report by the HRW documented the inability of many refugee children to enroll in public schools because their families could not afford transportation costs or because public schools refused to enroll them.

According to the report, 29% of 443 children reported in 2019 that Lebanese schools refused to allow Syrian children to take mandatory exams if they do not have legal residency in Lebanon, which is required starting at the age of 15, but 70% of Syrians cannot afford it or are not eligible to receive it.

Dilapidated sector, piling crises

The education sector in Lebanon has witnessed successive crises since 2019, all of which were met with suspended solutions, which delayed the return to school many times for Lebanese students and prevented Syrian students from returning in the first place.

The crisis of the Lebanese education sector worsened, affected by the banking crisis that appeared in 2019, and was followed by the Beirut port explosion in August 2020, which put Lebanon in confrontation with more economic problems, and contributed to more financial collapse in Lebanon, reinforced by the accompanying political and economic fluctuations, as well as the energy resource crisis that put the fuel market in a state of instability.

All of this led to the deterioration of the value of the Lebanese pound against the US dollar by more than 90%, making the education sector one of the most prominent sectors affected by these crises.

According to a World Bank report, one of the most prominent repercussions of the economic crisis on the education sector was the transfer of about 55,000 students from private education to public education due to the inability to pay tuition fees, which doubled the pressure on the government sector.

Statistics issued by the Center for Educational Research and Development (CRDP) in Lebanon showed that the percentage of students enrolled in free and non-free private education for the academic year 2017-2018 was about 66% of the total number of students, while this percentage decreased by about 6% in the academic year 2020-2021.

Distance education, additional pressure

Distance education was presented as an option for the first time after the Beirut port explosion, which resulted in damage to about 163 schools, and exposed at least one out of every four children in the city to the risk of losing their education.

While distance education has become necessary across the country with the spread of the (Covid-19) epidemic in 2020 and the great challenges it imposed on teachers, students, and their families.

In the past school year, 700,000 children, or a third of the school-age population, did not receive their education, while about 1,300,000 children received limited education as the education sector did not have suitable digital platforms for distance education.

A survey conducted by the Lebanese American University (LAU), the Center for Lebanese Studies, and the Local Engagement Refugee Research Network (LERRN) showed that the bulk of distance education in Lebanon relied on WhatsApp messenger without any preparations or directions on how to provide effective education through this application.

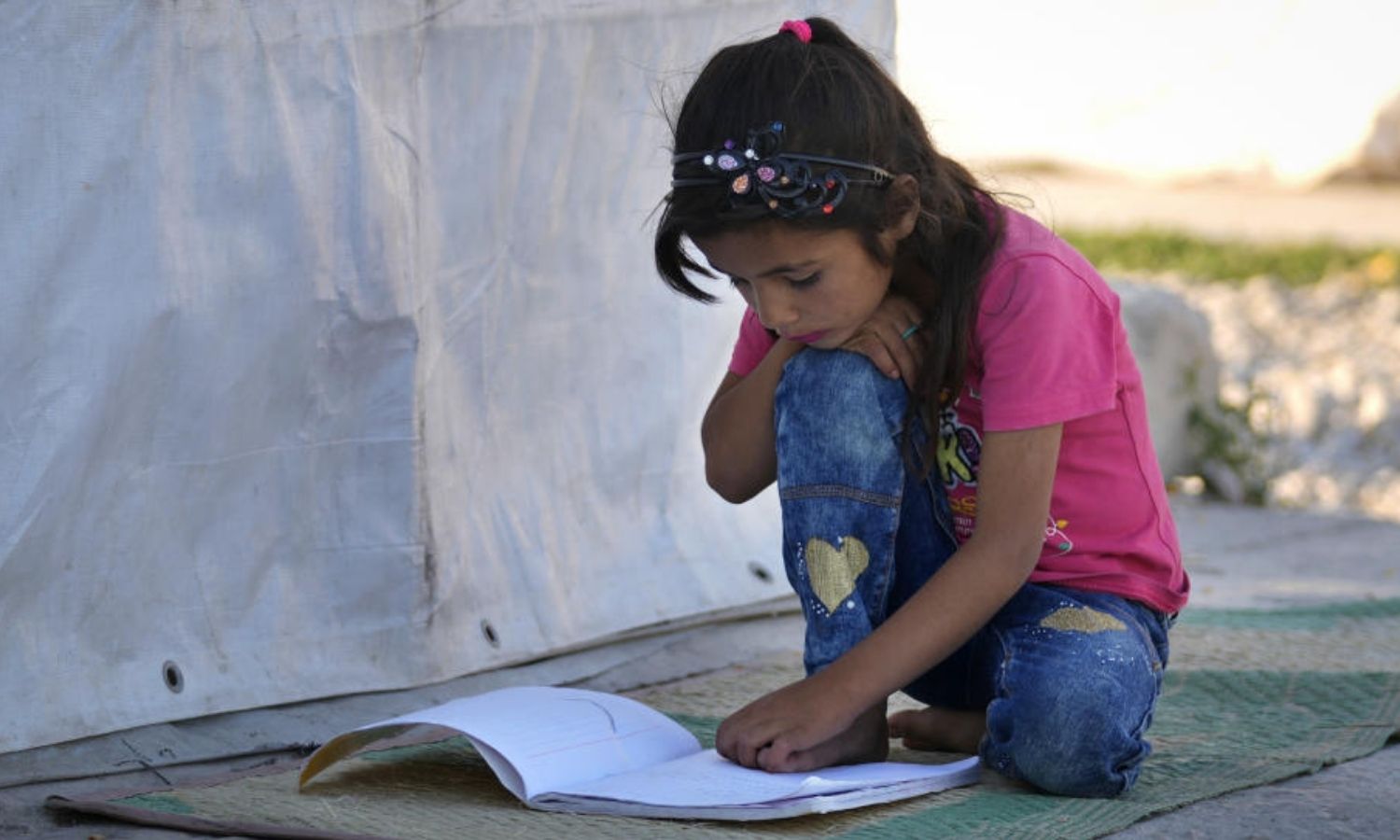

Hundreds of students, most of them Syrians, were also unable to access distance education due to their inability to secure smartphones and computers and the constant power outages.

This comes at a time when the Syrians are unable to provide the minimum expenditure necessary to ensure survival, as nine out of every ten Syrian refugees live in extreme poverty, according to a report by the UNHCR, World Food Program (WFP), and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) On 29 September 2021.

Teachers strike, “state corruption”

“My nine-grade daughter has not received any lessons so far,” Syrian refugee Adib al-Qaq told Enab Baladi, expressing his concern about the future of his daughter, Ghina, who is studying in the evening shift in a government school, accompanied by her brother Abdul-Hakim, who is in the sixth grade.

Al-Qaq added that the school administration told them a few days ago about the postponement of the start of the evening shift for Syrian students and attributed this to the teachers’ strike.

The ailing economic crises push Lebanese teachers to meet the date of the school year every year by organizing strikes and not attending schools in protest of the low value of their salaries that are not commensurate with the high cost of living in Lebanon, in addition to the delay in receiving their salaries and the failure to grant them incentives disbursed to them from the World Bank.

The strike intensifies during the evening hours reserved for Syrian students, despite the fact that half of the donor funds allocated to support Syrian refugees in Lebanon go to the education ministry.

The crisis in the salaries of teachers responsible for Syrian students is related to donors transferring aid in US dollars through the Central Bank of Lebanon, which takes most of the aid before it reaches the beneficiaries.

According to an investigation conducted by the Lebanese al-Jadeed channel, donors provide a specific amount in dollars for each Syrian student enrolled in a public school, relying on information provided by the Lebanese Ministry of Education, which manipulates numbers.

The investigation revealed that the ministry received an estimated surplus of about seven million dollars during the academic year 2019-2020 due to submitting reports to donors that include more students than the actual number.

Syrians not allowed to register in private schools

In practice, it is allowed if school tuition fees “in dollars”

Despite the donors’ pledge to bear all costs and fees, the Lebanese Ministry of Education refused to allow private schools to teach refugee students, saying in a statement issued on 27 September, “If the Lebanese do not have access to education, the non-Lebanese will also have no access, regardless of the methods and projects.”

The ministry affirmed that it does not accept any attempt to integrate displaced students and settle them through the private educational sector.

It described the integration of Syrian students in private schools as a “disguised settlement,” considering that its decision comes from “a clear national and educational policy, which requires returning the displaced to safe areas in Syria, which are many.”

The ministry threatened the owners of private schools, if they agreed to these offers, to take punitive measures against them, starting with not recognizing the legality of registering Syrian students, preventing those schools from receiving new students, stopping them from continuing teaching, and withdrawing their operating licenses when necessary.

In view of what refugees are subjected to in Lebanese public schools, many of them had the option of teaching their children in private schools, where the educational standard is raised and discriminatory treatment is somewhat reduced.

However, this option is no longer available officially this year, but in practice, according to what Enab Baladi monitored, many schools did not comply with this decision without clearing the reasons.

School tuition fees in dollars only

Before the start of the current school year, Hussein al-Khalaf, 32, enrolled his child Ali, 7, in the first grade and his daughter Samar, 4, in a “second kindergarten” class in the town of Ghadir in the Keserwan District, 22 kilometers northeast of the capital, Beirut.

Ali, who is supposed to be in the second grade, was a year late for enrollment previously in the kindergarten classes due to the family’s financial inability, which added an additional school year to him, as public and private schools in Lebanon set a condition for accepting any student in the first grade, which is that they finish studying in a minimum of one kindergarten class, among kindergarten classes starting at kindergarten one at three years old, kindergarten two at four years old, and a third at five years old.

Al-Khalaf, who works in a restaurant with a salary of 200 USD, chose a private school to educate his two children instead of public schools, given that the priority of enrollment in public schools is for Lebanese students.

In the event that Syrian students are accepted, the school sets their education hours in the afternoon until six in the evening, which is another obstacle for the parents.

Some Syrian families in Lebanon were forced to enroll their children in private schools as an alternative and compulsory solution, which placed on them financial burdens and costs that were not commensurate with their deteriorating economic and living conditions.

Al-Khalaf told Enab Baladi that the financial costs of the private school constitute an additional financial burden on the family and preoccupy them months before the start of each school season, especially the monthly installments.

He stated that he paid the registration fee for kindergarten and Grade 1 of 40 USD at the beginning of the school year.

Despite the insistence of the Minister of Education and Higher Education, Abbas al-Halabi, that tuition fees in private schools be paid in Lebanese pounds, this did not prevent a number of schools from imposing the payment of part of their tuition in dollars, taking advantage of the government decision refusing to educate displaced students in private schools.

Al-Halabi’s decision also carried several caveats, the violation of which is considered a legal violation, stating that non-free private schools may not impose any amounts, whatever their name or amount, on the parents of the students enrolled in them, in addition to the school fees they collect from each of them.

Extra expenses for private schools

School financial costs and burdens accompany the al-Khalaf family throughout the school year, depriving it of securing many needs, in addition to the costs imposed by daily life such as house rent, electricity, gas, water, food, medicine, and other bills.

Al-Khalaf pays 20 USD per month for a period of seven months, and the monthly installment for a first-grade student is 30 USD. The monthly payments increase as the grade rises, pointing out that books and stationery are bought by the students’ families.

Al-Khalaf paid about 50 USD for the books of the second kindergarten class, in addition to stationery such as notebooks, pens, and colors, and the books of the first grade amounted to about 100 USD. Also, the payments include the private school uniform that was purchased from the school at a value of 25 USD, and the first-grade student must purchase a sports uniform from the school authority at a value of 25 USD (it is a compulsory dress, students are not entered without adhering to the school uniform).

Each private school imposes its own school uniform that differs from other schools. In the event that a student is transferred from one school to another, he/she must purchase a new one.

Al-Khalaf uses his motorbike to transport his two children because he is unable to pay the 20 USD per week for the school bus, pointing out that the burdens of financial costs do not negate that private schools are better than public schools in terms of care and communication with parents, to improve the student’s educational level.

Bullying, one of reasons

Qais Ibrahim, 33, who works on a farm, enrolled his son Mohammad, 6, in the first grade, and his daughter Amira, 4, in the second kindergarten class in one of the private schools in the Saadiyat village, 26 kilometers from Beirut.

Being bullied in public schools and the limitation of school hours during the evening shift, in addition to the repeated interruption of education due to strikes, are sufficient reasons for Ibrahim to enroll his two children in a private school, he told Enab Baladi.

The school distributed a schedule of tuition fees and installments, set in Lebanese pounds, but there is no objection to parents paying in dollars.

Ibrahim pays 150 USD in installments for his son Mohammad, and 135 USD for his daughter Amira, during the year, which is divided into payments determined by the school, and a registration fee of 120 dollars for each child, in addition to 40 dollars for the school for school papers and publications.

He also paid 10 USD for school uniform and 30 USD for stationery, in addition to a 15 dollars bus fare for each student, which increases according to the distance of the area from the school, Ibrahim added.

Role of UN organizations

According to statistics issued by the UNHCR in September 2021, 30% of Syrian children in Lebanon of school age (from 6 to 17 years) have never attended school, while primary school enrollment decreased for children between (6 and 14 years) by 25% in 2021.

The upward trend in child labor among Syrians in Lebanon continued in 2021, as currently, no less than 27,825 Syrian refugee children work, and one out of every five girls between the ages of 15 and 19 is married, and about 56% of children between the ages of 1 and 14 have been subjected to at least one form of “violent discipline,” UNHCR’s stats showed.

UNHCR supports the evening shift

To find out the details of the role of the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) in ensuring the rights of Syrian children in Lebanon in the education sector and its dealings with the Lebanese authorities in this context, Enab Baladi contacted the organization, but it did not receive any response until the time of publishing this report.

Nadine Mazloum, official spokesperson for the UNHCR in Lebanon, told Enab Baladi that the UN agency is working closely with all partners, including the Lebanese government, to ensure the welfare and protection of refugee children in Lebanon.

With regard to the issue of education, the UNHCR supports the Ministry of Education and Higher Education and the implementation of the Lebanese government’s five-year plan on education and coordination with the ministry at the central and regional levels to call for overcoming the obstacles that prevent refugee students from accessing the national system, according to Mazloum.

However, the economic situation and the external financial environment pose a major challenge to ensuring that all children in Lebanon have access to education, she added.

Mazloum explained that the UNHCR did not exert any pressure on the Lebanese government to register refugees in the morning shift alongside Lebanese students, but its programs focused on community interventions.

The UNHCR activated the community education system (Liaison ECLs), which is a network of outreach volunteers who work in the second-shift schools to help with registration and student attendance.

The role of “ECL” is to enable communication between the school administration and parents, provide recreational activities, psychological, social, and homework assistance, prevent absences and dropouts and monitor school conditions, teaching methods, and refugees’ access to education.

UNHCR is also collaborating with its partners to provide homework help and parents’ groups, as well as basic literacy and numeracy projects outside of school, Mazloum concluded.

Solutions

Since the start of the Syrian displacement waves to Lebanon, many UN and international organizations have focused their efforts on ensuring the right to educate displaced children in Lebanon. However, the regional and international economic crises contributed to the lack of support and funding provided to them, which directly affected the educational reality in the country.

According to a report issued by the UNHCR in June 2021, international donors provide 300 million dollars annually to the education sector in Lebanon, but this amount covers a small part of needy students, as the master plan they fund covers school fees for only 528,000 Lebanese and Syrian children, in addition to school fees. The school that runs second-shift classes for Syrian students, of which only 41% were funded at the time.

An emergency plan, which has not yet been funded, targets 220,000 students, without including the Syrians in the evening shift or the Palestinians. The plan aims to provide families, schools, and teachers with in-kind and cash assistance.

Dr. Bassem Hatahet, governance expert, says that the root of the problem of the exacerbation of the education crisis for Syrian refugees in Lebanon, like all accompanying crises, is the absence of an organization, a political body, or an official human rights body that officially represents them, defending their rights and protecting them from exposure to abuse or human rights violations.

The researcher and trainer in civil society organizations added to Enab Baladi that the Lebanese government’s policy reinforces this crisis, as all the international organizations that provide aid to the Syrian refugees are intermediate organizations that provide services to them as displaced persons and non-permanent guests, because the government considers them as such, and the work of these organizations is directly controlled by the government.

The principle in the issue of education is that refugees obtain their full right to education when the government recognizes their right to humanitarian protection.

However, since the Lebanese government is dealing with this file with a kind of pressure on the international community, the educational process is considered one of the most important programs in which the rights of Syrian children are severely violated, according to Hatahet.

A “hazy” future as deportation begins

On 26 October, the first batch of Syrian refugees in Lebanon arrived in the Syrian territories, according to the Lebanese government’s plan to return the refugees.

The state-run SANA stated that a batch of “displaced” Syrians arrived from the Lebanese camps through the Dabousieh border crossing with Homs countryside, “returning to their safe areas that were liberated from terrorism.”

On 4 July, Issam Sharaf El-Din, Minister of the Displaced in the Lebanese caretaker government, revealed a Lebanese plan that provides for the return of 15,000 “displaced” Syrians from Lebanon on a monthly basis, but only 511 people have returned, according to the latest statement issued by the Lebanese General Security in December.

At the time, he said, “It is completely unacceptable that the displaced Syrians do not return to their country after the war ends and it becomes safe.”

At the same time, he pointed to a plan to form a tripartite committee that includes the Syrian regime and the UNHCR, as well as a quartet committee consisting of Turkey, Iraq, Jordan, and Lebanon to achieve this “return.”

Dr. Bassem Hatahet considered that in light of the current circumstances, it is not possible to look positively at the future of education in Lebanon, and as long as the government is pressing for the return of refugees, this creates uncertainty in the position of the Lebanese government on all human rights issues in Lebanon.

Regarding solutions, Hatahet explained that in order for the process of educating Syrian children in Lebanon to take place normally or for it to improve and develop, five main rules must be relied upon:

- Establishing a higher council for the education of Syrian refugees in Lebanon that includes representatives of international organizations and representatives of refugees (camp principals or an elected committee to represent Syrians).

- The council should obtain recognition from two main parties, international organizations and the Lebanese Ministry of Education, with the aim of working within joint cooperation to find solutions.

- Subjecting the teaching process to the perspective, logic, or rules of temporary humanitarian protection (the United Nations and donors pay the Lebanese government for this matter).

- To ensure positive results, the file on children’s education in Lebanon must become one of the responsibilities of the official representatives of the Syrian opposition, as it is one of the most important files with which they should report to the recognized UN bodies.

- Establishing an entity, committee, or organization whose work is represented by two tasks, the first is monitoring and documentation, and the second is a media role so that monitoring and documenting the progress of the educational process through the media will be raised to decision-making centers.

if you think the article contain wrong information or you have additional details Send Correction

النسخة العربية من المقال

-

Follow us :

Most viewed

- Kurdish Protection Units: Key point of contention between Damascus and SDF

- Arrests and explosive seizures in security campaign in old Damascus

- Syria and Lebanon sign agreement for cooperation in border demarcation

- Struggle for Syrian phosphate awaits fate of Russian contract

- Koya: A border village paying the price for rejecting Israeli presence

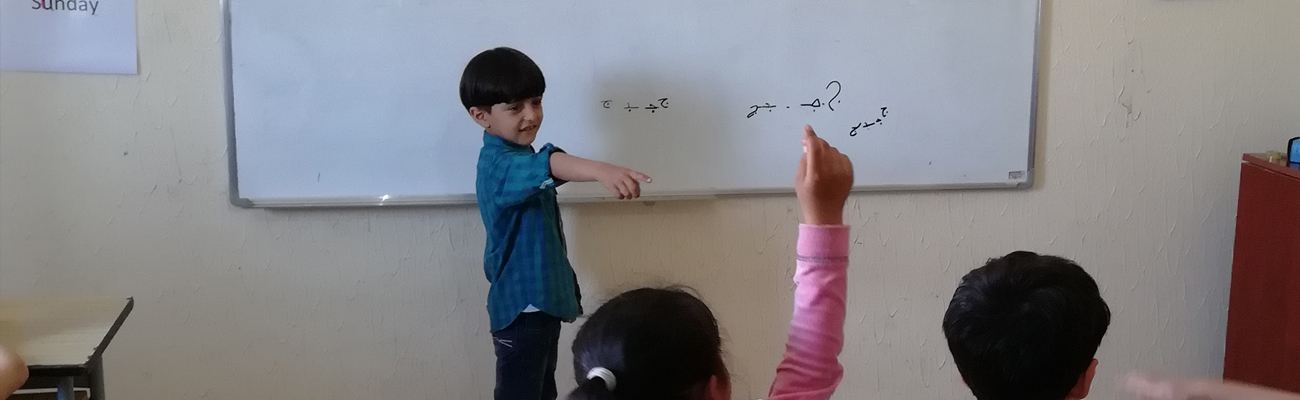

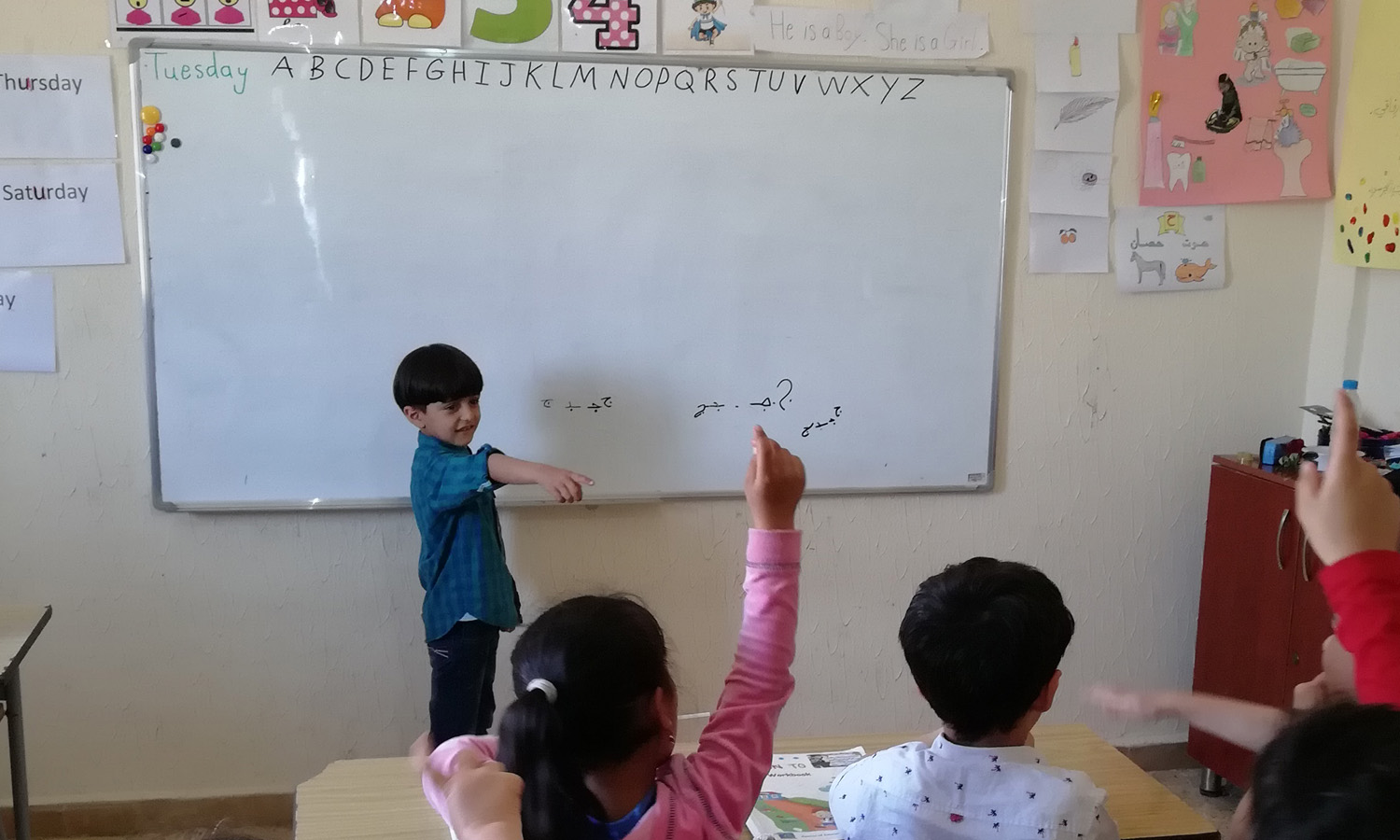

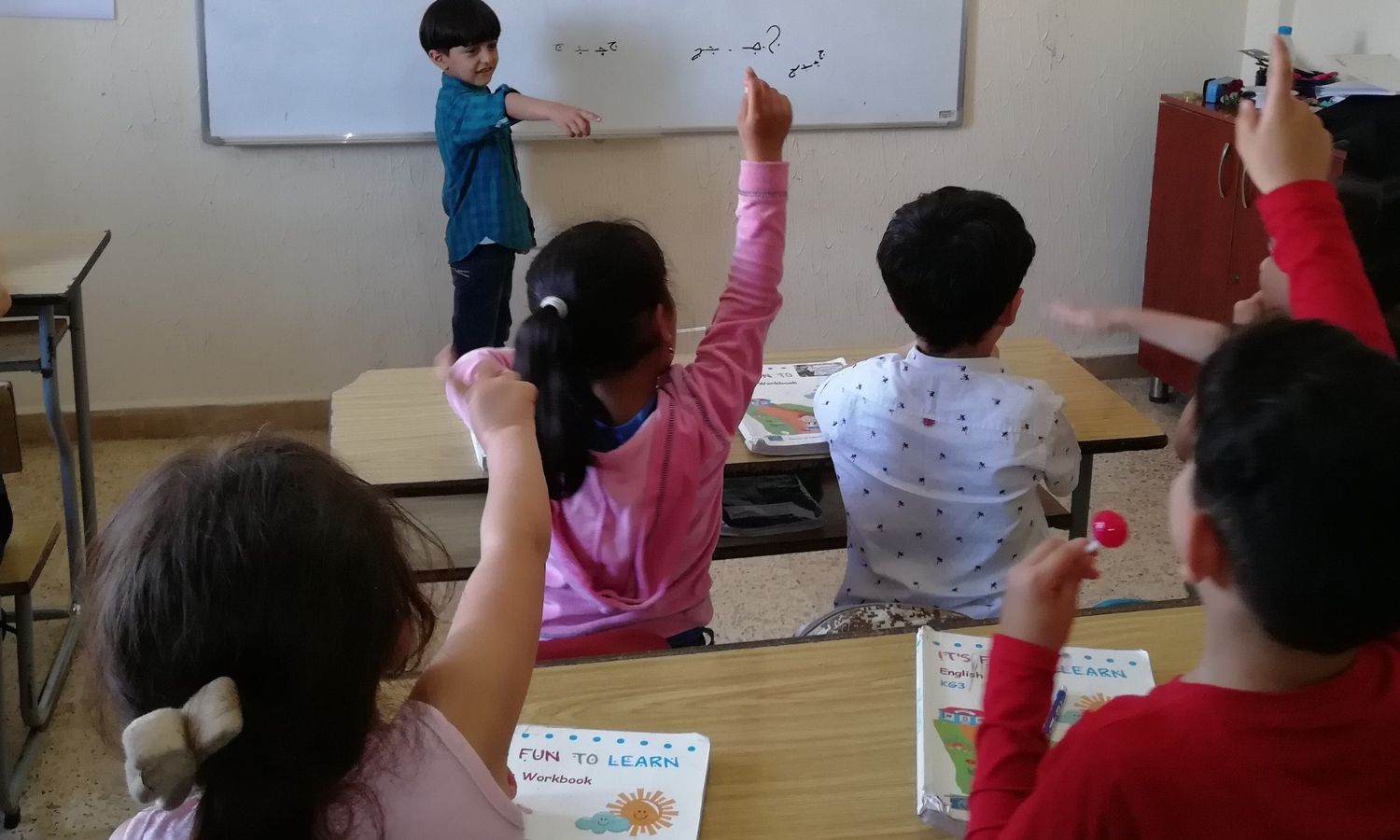

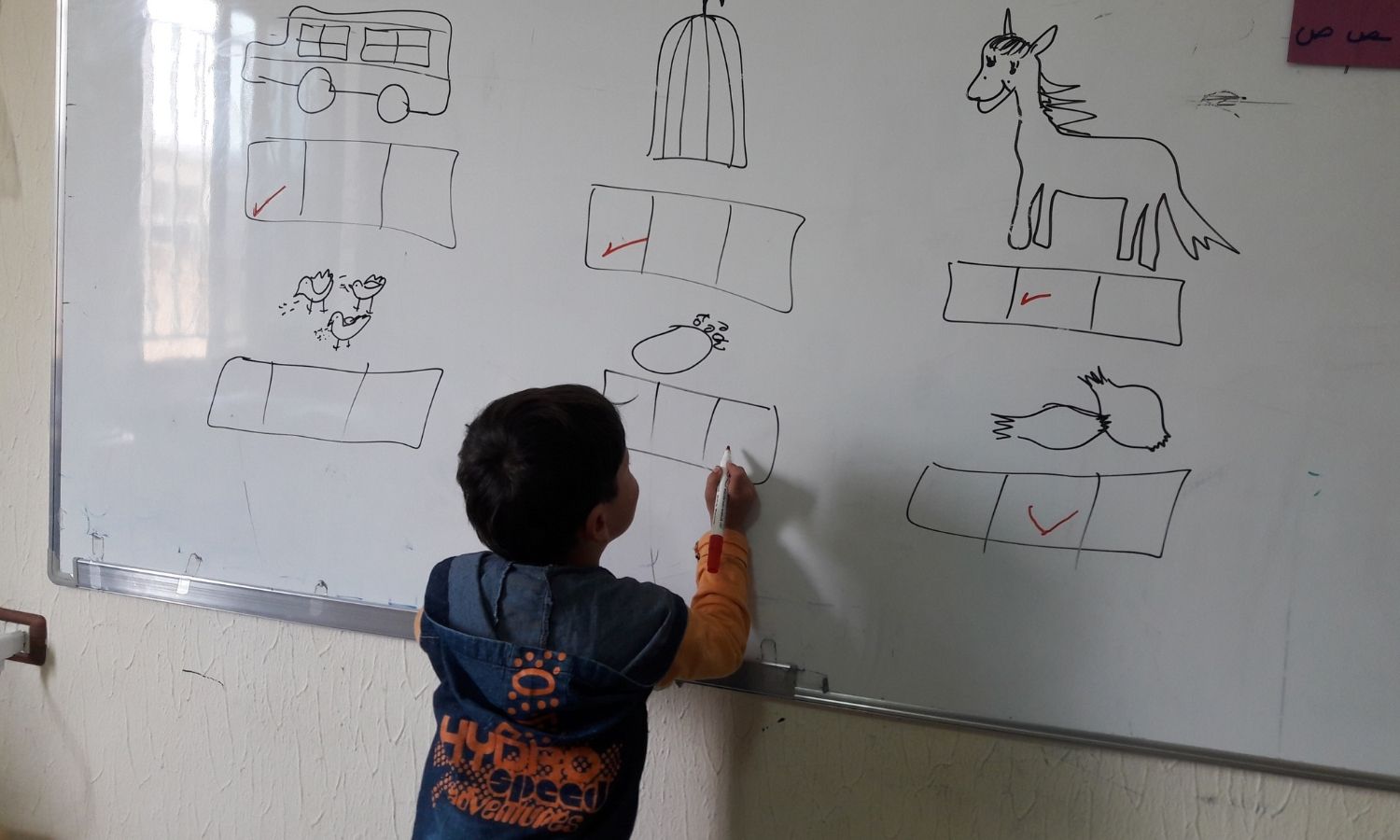

Elementary students at a school in the Marj al-Beqaa region in Lebanon (Gharsa Education Center)

Elementary students at a school in the Marj al-Beqaa region in Lebanon (Gharsa Education Center)

A

A

A

A

A

A

More In-Depth

More In-Depth