Mamoun al-Bustani | Jana al-Issa | Amal Rantisi | Muhammed Fansa

Eight hectares of irrigated wheat are all owned by farmer Ibrahim Suleiman in the countryside of the town of al-Qahtaniyah, northeast of al-Hasakah governorate in Syria.

Suleiman, 41, is “impatiently” waiting for the harvest to begin in the Syrian Jazira region, the home of yellow gold (wheat), but what concerns him is far from securing the harvesting machine, workers, and harvest sacks but rather a political-economic struggle over its production between two main poles, the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES) and the Syrian regime.

The signs of the conflict over wheat hide behind the fear of a “famine” that threatens millions of Syrians, with Syria turning into an importing country after it was an exporter of wheat during the past years.

Concerns arose with a crisis that stopped supplies from Russia as a result of the war on Ukraine, and then India banned the export of wheat, which was seen as an alternative to securing the domestic need of grain for the war-torn country.

According to what the UN said last February, food security figures are tracking and besieging Syrians, as Syria ranked first among the ten most food-insecure countries in the world this year, with 12 million people suffering from limited or uncertain access to food.

Also, the World Food Programme (WFP) announced, in its annual report for the year 2021, that three out of five Syrians suffer from food insecurity after the continuous rise in food prices and the deterioration of the economy throughout Syria.

In this in-depth article, by monitoring farmers’ testimonies, Enab Baladi reviews the procedures of local authorities in various regions of Syria to acquire the wheat crop and discusses with economic experts the resulting effects, in addition to the suspension of wheat supplies by major countries and its repercussions on prices and food security.

Price war to acquire Syrian wheat

The farmer Ibrahim Suleiman in al-Qahtaniyah considered that the price set by the Autonomous Administration is much better than the price set by the Syrian regime, especially since the latter does not provide anything in return, “no fuel or fertilizer,” while the Administration provided him with fuel during the watering period (15 liters of diesel per dunum at the rate of four batches).

He told Enab Baladi that farmers who own rainfed lands in the Autonomous Administration areas are obliged in any case to market their crops to the Administration, which circulated to the farmers of the region that everyone who sells their crop to other than the Administration will have its quantity confiscated, and the farmer along with the owner of the transport vehicle will be held accountable.

According to what Enab Baladi monitored, most farmers prefer to sell their crops to the Autonomous Administration because the supply process is closer, easier, and safer than supplying the crop to the Syrian regime.

On the other hand, farmers in the regime-held areas in the countryside of Qamishli city are forced to supply their crops to the regime.

Harvesting the wheat crop in the villages of the Barisha Mountain region, north of Idlib – 30 May 2021 (Enab Baladi / Iyad Abdul Jawad)

Kurdish Administration vs. Regime

With the beginning of each harvest season in Syria, competition to buy wheat from farmers intensifies, especially between the Syrian regime and the Autonomous Administration and, to a lesser extent, from the Salvation and Interim governments in northwestern Syria, with each party setting a higher purchase price for the crop, providing facilities for the transfer of the crop, and preparing centers to receive it.

On 14 May, the Syrian regime’s government set the purchase price of a kilogram of wheat from farmers in “safe areas” (regime’s areas of influence) at 1,700 Syrian pounds, with a reward of 300 pounds (about 50 US cents), according to the exchange rate of the Syrian pound against the US dollar at the time.

The government of the regime stated that it would give a reward of 400 Syrian pounds for every kilogram delivered from “unsafe” areas (out of the regime’s control), bringing the price of a kilogram to 2,100 pounds.

For its part, the Autonomous Administration set, on 23 May, a price higher than the regime for buying wheat in its areas of influence, as the price of a kilogram of wheat reached 2,200 Syrian pounds (about 55 US cents).

The Administration promised facilitations in wheat quality inspection, specifying the start of receiving the crop in Raqqa, Deir Ezzor, and al-Tabqa on 25 May and in the Jazira region on 28 May.

Delayed pricing in Interim and Salvation governments’ areas

The Syrian opposition’s Interim Government has not yet announced the purchase price of the current season’s wheat crop in its areas of control in the northern and eastern countryside of Aleppo, the Tal Abyad area in the northern countryside of Raqqa, and Ras al-Ain in the northwestern countryside of al-Hasakah.

In an interview with Enab Baladi, the Minister of Economy in the Syrian Interim Government (SIG), Abdul Hakim al-Masri, said that the government had formed two committees, one in the eastern Euphrates region (Ras al-Ain and Tal Abyad) and the other in the western Euphrates region, to present proposals for the price of wheat for the current season.

He added that wheat pricing will be issued as soon as the two committees submit their proposals on pricing, in light of international changes and global prices, taking into account the cost to the farmer.

Al-Masri pointed out that in the event of insufficient production, the Interim government will buy quantities of wheat from Ras al-Ain and Tal Abyad and transport it through Turkey to its areas in northwestern Syria.

Al-Masri stated that production in the western Euphrates region is low, while in the east, it is better due to the presence of irrigated areas. Officials of the agricultural directorates of the Interim government estimated the production of between 40,000 and 50,000 tons of wheat from the areas of Tal Abyad and Ras al-Ain.

For its part, the Syrian Salvation Government (SSG) operating in Idlib governorate and in parts of the western countryside of Aleppo has not yet determined the price of wheat purchase, and Enab Baladi contacted its Ministry of Economy, which stated that the price has not yet been determined.

Price differences don’t help

Economic researcher Zaki Mahshi told Enab Baladi that the different purchase prices of wheat from farmers, which are determined by the regime’s government, the Autonomous Administration, and the Interim and Salvation governments, cannot be in the interest of the farmers because they are basically not affordable.

The researcher at the London School of Economics explained the difference in prices with the authorities’ fear that bread would not reach families, which would lead to social complications or unrest that they were not about to fall into.

He added that these local authorities are also interested in competition to distribute resources among the dominant powers and for each of them to obtain a larger amount of local production in order to provide the import of additional quantities of wheat in foreign exchange.

Burning the wheat crop before it is ripe to prepare freekeh grains in the eastern countryside of Idlib – 16 May 2022 (Enab Baladi / Iyad Abdul Jawad)

Regime forces blackmail farmers

Ahmed (a pseudonym, as he reserved his real name for security concerns), who owns several hectares of wheat planted south of Qamishli Airport, told Enab Baladi that he had no other choice but to supply the crop to the Syrian regime.

Ahmed accused the regime forces of blackmailing farmers during the supply operations during each harvest season through dozens of checkpoints deployed in the area “on the pretext of protecting and preventing wheat smuggling” while imposing royalties and fees on all transport vehicles.

He pointed out that sometimes the unloading of the loads inside the grain centers is delayed as a result of the practices of the regime’s checkpoints, which leads to the extension of the long queues, forcing the farmer to pay additional amounts to the owner of the transport vehicle for each day of waiting.

Enab Baladi learned from a number of farmers that grain merchants are more active in regime-controlled areas than in Autonomous Administration areas, where they can pay bribes to regime checkpoints and deal with officers who receive certain amounts in exchange for allowing them to cross.

Impurities force wheat selling to merchants

Ali, 50, a farmer from the eastern countryside of Raqqa, decided to sell the wheat crop as soon as it is harvested to a grain merchant in the city of Raqqa at a price of 2000 Syrian pounds per kilogram, which is two hundred pounds less than the price set by the Autonomous Administration.

Ali told Enab Baladi, after requesting that his full name not be used, that he had to sell his crop to the merchant at a price even lower than the price of the Administration because he fears that the receiving centers will deduct the wheat price, on the pretext that there are impurities within the wheat grains according to the grading system adopted by the Autonomous Administration.

The Administration in its wheat receiving centers follows the grading system, which is a system for evaluating the quality of the wheat crop when it is received from farmers, in the light of which the appropriate price for the crop is determined, which is often lower than the price that the Administration usually sets.

Farmers from the countryside of Raqqa rule out the possibility of handing over their crops to the centers affiliated with the Syrian regime, which it has opened in areas under its control in the city’s countryside.

The Autonomous Administration prevents the transfer of the four strategic crops (cotton, wheat, corn, and barley), whether inside or outside its areas of control, without a certificate of origin issued by the Agricultural Development Company. This certificate authorizes the farmer to transfer his crop within specific areas and a specific date.

On 19 May, the Agriculture and Irrigation Committee issued a circular ordering farmers to hand over the wheat crop to the Autonomous Administration institutions in the city of al-Tabqa, west of Raqqa, threatening to cancel the agricultural license for the summer and winter seasons for the violating farmer, whether he is an owner or a tenant.

Priority to who provides services

Abdulqader, 44, a farmer from the villages of al-Hamrat in the eastern countryside of Raqqa, told Enab Baladi that he saw himself forced to sell his crop to a grain merchant in Raqqa city.

Abdulqader explained that he had to borrow from the merchant the cost of cultivating the wheat crop for the duration of its cultivation, on the condition that the crop be delivered to him as soon as it is harvested, which will certainly happen, he said.

He pointed out that the Administration does not provide the agricultural requirements necessary for growing the crop and delays the delivery of fuel, which prompts farmers to search for alternatives, and they are forced at the time of the season not to deliver their crops to the centers affiliated with the Autonomous Administration.

Meanwhile, farmers suggested the possibility of handing over their crops to the Administration centers, considering that they signed contracts with the Agricultural Development Company to provide them with improved seeds, which is supposed to top the price set by the Administration.

A member of the Agriculture and Irrigation Committee of the Raqqa Civil Council, who refused to reveal his name because he is not authorized to speak to the media, told Enab Baladi that the Autonomous Administration will try to purchase the entire wheat crop from farmers and will take the necessary measures in this regard.

He added that the Administration pays great attention to the purchase of wheat, but the grading system used is an old system even from the days of the Syrian regime and depends mainly on the degree of cleanliness of the wheat material and its freedom from impurities.

As for supporting farmers with agricultural inputs and fuel, he indicated that the support provided is among the capabilities available to the Autonomous Administration, which is working to increase and improve them in the future.

Daraa, Seed Multiplication Corporation is present

Muhammed al-Qasim, 65, of the Tell Shihab town, in the southern Daraa governorate, told Enab Baladi that he planted 20 dunums of wheat seed on rainwater in December 2021, and one dunum needed about 35 kilograms of seed at a price of 2,500 Syrian pounds.

He added that he faced several difficulties, including the spread of field mice and insects, which prompted him to use medicines in larger quantities and thus increase costs.

Al-Qasim indicated that he started irrigating the crop from wells’ water in March, explaining that for every hour of operation of the irrigation water-pumping generators, approximately five liters of diesel are consumed, the price of which has reached 4,300 Syrian pounds per liter.

He stated that he received 40 liters of subsidized diesel at a price of 600 Syrian pounds and 60 liters of unsubsidized diesel at a price of 1,700 pounds per liter, pointing out that these quantities do not cover a quarter of his need for diesel to irrigate his crop.

Al-Qasim expected a good return from the irrigated crop, while the rainfed wheat crop would not enter the production process this year due to the lack of rain.

According to al-Qasim, some farmers in the area decided to keep their crops in the hope of higher prices, while he would hand his crop over to the Seed Multiplication Corporation as it handed him diesel and fertilizers and he signed papers pledging to hand it over the crop.

Idlib, the soft loan

Saleh al-Issa, 45, a farmer from the al-Rouj Plain region, west of Idlib city, told Enab Baladi that the wheat harvest has not yet begun, expecting that the farmers will sell the wheat crop to the merchants.

He stated that farmers who have livestock in large numbers will leave a large part of the wheat crop as fodder, especially in light of the high prices of fodder.

Al-Issa pointed out that some farmers who obtained the interest-free loan from the Salvation government will hand over the crop to the government or sell it to merchants.

He explained that at the beginning of this year, a number of farmers who did not have the financial ability to cultivate their fields applied for a soft loan, which includes handing over wheat seeds, fertilizers, and agricultural medicines as of last February.

Among the conditions for obtaining the loan are the presentation of identification papers, the presence of sponsors from the people of the area, the approval of the Farmers’ Association, and the delivery of the wheat crop to the Salvation government or the return of the financial advance after selling the crop to the merchants, no later than the 15th of next July, al-Issa said.

According to the conditions for obtaining a soft loan, wheat seed was obtained at the price of 2021 (350 US dollars per ton), and the price of a bag of fertilizer (50 kilograms) was received at 35 US dollars al-Issa said.

He added that the current harvest season is acceptable, despite the difficulties farmers are facing with regard to the high costs of cultivation, irrigation, and labor, in addition to the lack of agricultural medicines.

Harvesting the wheat crop before it is ripe for the preparation of freekeh grains in the eastern countryside of Idlib – 16 May 2022 (Enab Baladi / Iyad Abdul Jawad)

Aleppo, ORGs support

Farmer Qassem al-Ahmad, 44, of Qabasin town in the northeastern countryside of Aleppo, told Enab Baladi that one of the most important difficulties farmers faced during the current season is the high costs of irrigating the wheat crop due to the high price of diesel (100 US dollars per barrel), especially in light of the drought wave that hit the region as a result of the lack of rainfall, which led to an increase in the consumption of diesel.

Al-Ahmad explained that he irrigated the crop twice only due to the high price of diesel, which will lead to weak wheat growth and, consequently, a decrease in production.

The farmer had not harvested the wheat crop yet, indicating that he wanted to sell the crop after harvesting it to a local organization that had supported him with wheat seed because the organization was working on multiplying the seeds.

“This year, my name was among the farmers who received support from the (Hand in Hand) and (Violet) organizations to grow wheat,” al-Ahmad told Enab Baladi, pointing out that the crop has not been sold so far, not to the organizations nor to Turkey, which is active in supporting the region’s institutions and there are facilities for traders to transfer the crop to it.

He noted that in 2021, traders received the crop at a price higher than the price of the organizations (350 US dollars per ton).

|

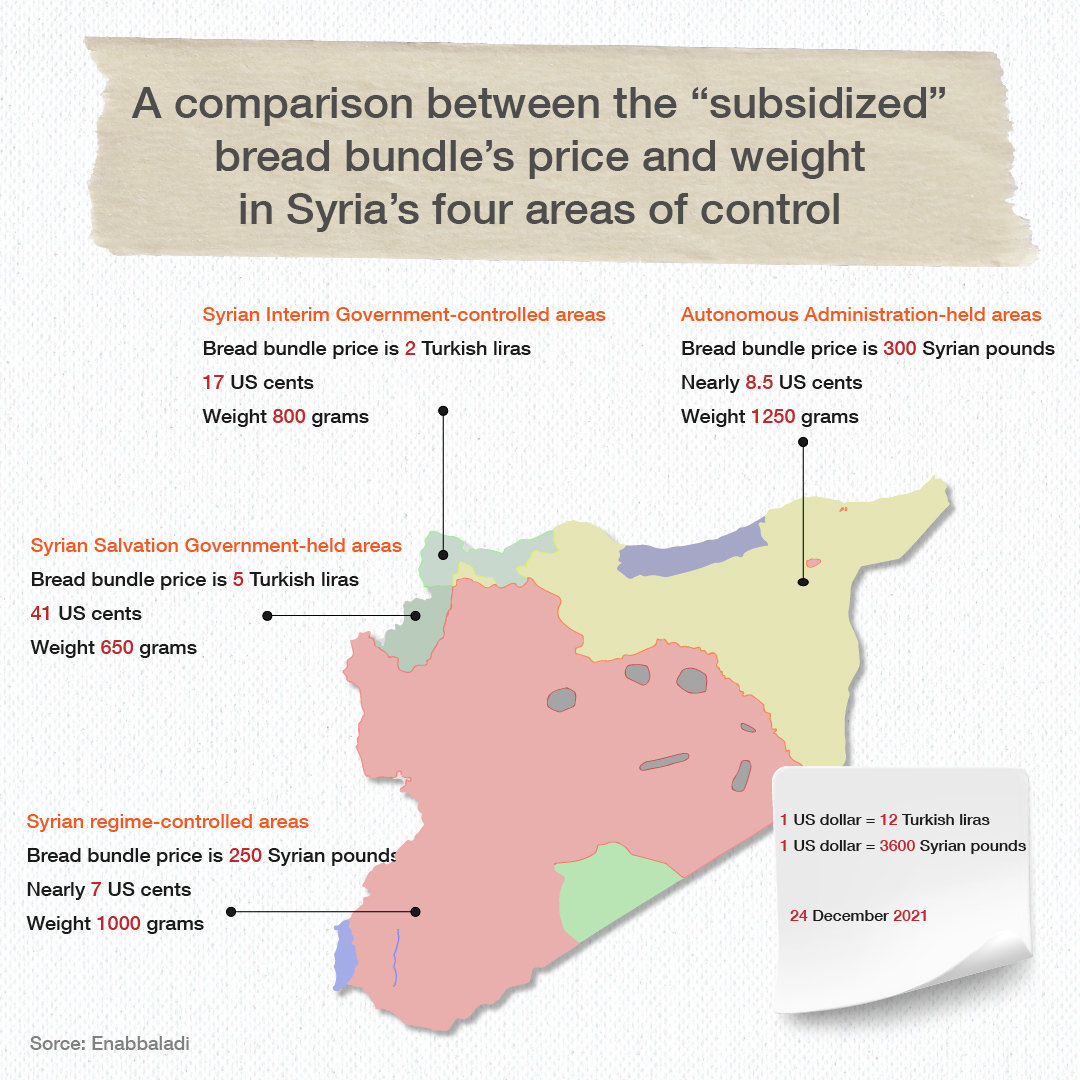

The currencies adopted differ in the three main regions of Syria. While the regions of the Syrian regime and the Kurdish-led Autonomous Administration depend mainly on the Syrian pound, the US dollar and the Turkish lira are traded in northwestern Syria. One US dollar is trading in the markets at 4000 for the Syrian pound and is trading at 16 for the Turkish lira. |

Syrians confused by supplies suspension

Syrians confused by supplies suspension

The turmoil in the global wheat export market since the start of the Russian war on Ukraine on 24 February was a direct reason for the rise in wheat prices amid the growing fear of the exacerbation of the global food crisis.

Russia and Ukraine are among the largest exporters of grain, including wheat, with wheat exports from both countries amounting to more than 30 percent of the world’s exports annually.

On 4 May, the WFP said that the war in Ukraine revealed the fragility of global supply chains and their vulnerability to global food price shocks, which portend dire consequences for global food security.

On 16 May, the British Financial Times newspaper said in a report that the benchmark wheat index “rose as much as 5.9 percent to 12.47 US dollars a bushel, their highest level in two months. Wheat prices have risen more than 60 percent this year, driven up by disruption from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The two European countries account for almost a third of the world’s wheat exports.”

India’s announcement on 14 May to ban wheat exports to combat inflation in the country constituted a new blow to global markets, which are already suffering from a lack of supplies due to production problems in the traditional export powers of Canada, Europe, and Australia, and the disruption of supply lines in the war-torn Black Sea region.

China called for the need to establish a “green corridor” for the export of Russian and Ukrainian grain, while the United States and the International Monetary Fund urged India to reconsider the decision to ban the export of wheat.

Alternatives

Syria is one of the countries that mainly depends on the import of wheat from Russia and Ukraine. However, the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and the imposition of sanctions on Russia by Western countries, restricted the movement of maritime traffic in the Black Sea, which prompted the Syrian regime to search for alternatives to Russian supplies.

Russia announced a ban on wheat exports last March, prompting the Director-General of the Syrian Grain Corporation, Abdullatif al-Amin, to confirm that the Corporation intends to contract to supply 200,000 tons of wheat from India and is also looking for alternative options for importing wheat.

Al-Amin said at the time that the Grain Corporation is looking for alternative options for Russia to import wheat because of its high prices only, pointing out that Russia’s decision to prevent wheat exports does not apply to Syria.

On 18 March, the Syrian regime’s Minister of Internal Trade, Amr Salem, said, “While several countries in the region and the West announce their expectations for a wheat and flour crisis, the situation of wheat stocks in the Syrian Arab Republic is fine.”

At the time, Salem stated, on his Facebook page, that the government does not import wheat from Ukraine, but rather all its imports are from “friendly” Russia, and does not apply Western sanctions, and does not need to import wheat from any other countries.

Following India’s announcement of a ban on wheat exports earlier this month, the Syrian ambassador to Russia, Riad Haddad, said that Russian supplies of basic needs in Syria are taking place on a continuous and stable basis, noting that Russia excluded Syria from all the measures it took recently with regard to the export of products, especially wheat.

Haddad stated, in statements carried by the local pro-government newspaper, al-Watan, on 21 May, that a new batch of Russian aid will arrive in Syria next month, approximately 160 tons of wheat.

Exception, smuggling

The statements of Syrian regime officials about the Russian exceptions to the wheat export ban and the continuation of supplies to Syria came amid media reports that Russian ships transported stolen wheat from Ukraine to Russia.

On 12 May, CNN uncovered that a “Russian merchant ship loaded with grain stolen from Ukraine has been turned away from at least one Mediterranean port and is now in the Syrian port of Latakia, according to shipping sources and Ukrainian officials.”

CNN has identified the vessel as the bulk carrier Matros Pozynich.

“On 27 April, the ship weighed anchor off the coast of Crimea and turned off its transponder. The next day it was seen at the port of Sevastopol, the main port in Crimea, according to photographs and satellite images,” CNN said.

Adding that “the Matros Pozynich is one of three ships involved in the trade of stolen grain, according to open-source research and Ukrainian officials.”

From Sevastopol, according to satellite images and tracking data reviewed by CNN, the Matros Pozynich transited the Bosphorus and made its way to the Egyptian port of Alexandria. It was laden with nearly 30,000 tons of (Ukrainian) wheat, according to Ukrainian officials.

Mikhail Voytenko, editor-in-chief of the Maritime Bulletin, told CNN that the grain could be reloaded onto another ship at Latakia to disguise its origins. “When the destination port starts to change without any serious reason, this is another proof of smuggling,” he said.

The Syrian regime has a close relationship with Russia, and the Russian military are frequently in Latakia. Indeed, the Matros Pozynich is named after a Russian soldier killed in Syria in 2015.

The Ukrainian Defense Ministry’s Intelligence Directorate said that “a significant part of the grain stolen from Ukraine is on vessels sailing under the Russian flag in the waters of the Mediterranean,” CNN reported.

“The most likely destination of the cargo is Syria. The grain can be smuggled from there to other countries of the Middle East,” it said.

“The Ukrainian Defense Ministry estimates that at least 400,000 tons of grain have been stolen and taken out of Ukraine since Russia’s invasion,” CNN reported.

Mykola Solsky, Ukraine’s Minister of Agrarian Policy and Food, said this week it is “sent in an organized manner in the direction of Crimea. This is a big business that is supervised by people of the highest level.”

Syria as key wheat importer

Karam Shaar, Syrian professor in economics and director of research at the Operations and Policy Center (OPC), said in an interview with Enab Baladi that “the economic situation in Syria is currently at its worst stage, as it has not been this bad since the First World War when Syria experienced a real famine.”

The Syrian academic added that “the wheat problem in Syria is currently a complex problem, and one of the most important reasons for it is that Syria is experiencing the worst drought in decades,” noting that this wave “started since last year and is still continuing this year despite the improvement in rainfall this season.”

Dr. Shaar suggested that Syria would turn into a major importer of wheat, not only in the areas of the Syrian regime but even in the areas controlled by the Autonomous Administration in northeastern Syria.

He pointed out that the Administration has allocated funds in the current budget to import wheat, despite the fact that its areas of control are considered Syria’s basket of wheat production, as wheat production in those areas amounts to about 60 percent of Syria’s total production.

The economic expert stressed that there is a great need for wheat in Syria, and the Syrian regime’s regions suffer from a lack of financial resources to import, pointing out that in addition to the drought that is hitting Syria, “the regime is unable to import externally, especially since wheat prices have skyrocketed for several reasons, The first was the problems in global supply chains, but later they rose again due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine and India’s ban on exports,” he said.

Burning the wheat crop before it is ripe to prepare freekeh grains in the eastern countryside of Idlib – 16 May 2022 (Enab Baladi / Iyad Abdul Jawad)

The crisis is global…

Price and quality of Syrian bread “at stake”

Since the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the UN and human rights organizations have repeatedly warned that Syria will be exposed to an “imminent” famine, along with many additional reasons that pose a real threat to the food security of Syrians.

Indicators have multiplied to be directly reflected on the main food entry for Syrians today, which is bread, starting with the drought and low levels of local wheat production, passing through the “weak” agricultural policies of the controlling parties in the various Syrian governorates and the weakness of the agricultural sector, and not ending with the rise in fertilizer prices and the difficulty of importing.

Like every economic or living crisis, the Syrians’ share of suffering is the largest and most affected part, as the crises reflect on their lives and increase their suffering in obtaining their daily sustenance.

Bread is considered a basic commodity and a nutritional component of their meals, which lack the presence of meat, vegetables, fruits, and milk. This is accompanied by the deterioration of the purchasing power of citizens and the gap between wages and consumption.

Poll

Enab Baladi conducted an opinion poll on its website on the bread crisis and its aggravation in Syria.

The results were mixed, as 69 percent of the respondents voted that the Syrian regime’s inability to find solutions is the main reason for the aggravation of the bread crisis, while 31 percent of the respondents attributed the reason to the rise in prices globally.

Zaki Mahshi, a researcher in international economics, confirms that the reflection of the global wheat crisis will have the greatest impact on Syrian families through the methods that the various “governments” and the de-facto forces controlling the various governorates will resort to deal with the decrease in the quantities of wheat they have.

The researcher explained to Enab Baladi that governments will try to work according to the existing low quantities, and thus this will affect the quality of bread production and the increase in its prices.

The researcher believes that the liberalization of bread prices, which the regime has started with since its adoption of the “smart card” in 2018, has created a black market for the sale of the material, which has increased the burdens of families, expecting that these families will resort to the black market more in the future due to the limited quantities that will be available with subsidies, the matter which guarantees a high price as a result of the large demand for it.

The rise in bread prices will affect the consumption behavior of families in terms of materials and other necessities, such as giving up some of the health and education expenses, in order to secure the minimum amount of food, which is bread, according to the researcher.

Mahshi believes that the increase in living crises and their arrival in a loaf of bread would contribute to an increase in negative social phenomena throughout the Syrian geography.

The expert warned that food poverty may force people to resort to other ways to obtain money, such as theft, kidnapping, and smuggling, to secure their needs, which will plunge the Syrian economy at the local level into a new cycle of crises.

Regime areas will be affected

The regions of northwestern and northeastern Syria had, during the years of conflict, the possibility of importing quantities of wheat from other countries such as Turkey and Iraqi Kurdistan, and the estimated values of wheat production in them are greater than the values of production in the areas under the control of the regime.

However, this may not remain possible at the present time in light of a global crisis to secure the material, which will raise the prices of wheat, flour, and bread around the world as well, according to Mahshi.

The researcher added that all Syrian governorates are almost equally affected by the wheat crisis, and it will have a somewhat similar impact on people, given the lens of the general economic situation, regardless of the dominant party, and in the presence of a high poverty rate, the effects will be doubled for everyone.

Mahshi recommends the necessity of distinguishing in the regime-controlled areas between crony capitalism and the beneficiaries of the war and the regime and the rest of the Syrian people.

He added that the beneficiaries will benefit from any crisis through the shadow companies, where they can import wheat for the benefit of the government of the Syrian regime, with a very high-profit margin under the pretext of the global crisis.

if you think the article contain wrong information or you have additional details Send Correction

النسخة العربية من المقال

-

Follow us :

Wheat harvest in al-Hasakah countryside - 2021 (North Press Agency)

Wheat harvest in al-Hasakah countryside - 2021 (North Press Agency)

A

A

A

A

A

A

More In-Depth

More In-Depth