Zeinab Masri | Hassan Ibrahim | Jana al-Issa | Hussam al-Mahmoud

The 28-year-old Fatima al-Hamid was killed on an engagement line separating the ‘liberated region’ into two areas. The young lady was carrying a few liters of heating fuel to repel the winter cold away from her children in a try to save a few Turkish piasters as prices differed between the one geographical boundary.

A guard of the Atmeh-Deir Ballout crossing opened fire at al-Hamid’s head, claiming that “she was killed by mistake” when a clash flared at the same time with “smugglers” who were transporting prohibited materials from the Syrian Interim Government (SIG) areas in the countryside of Aleppo to Idlib region that is controlled by to the Syrian Salvation Government (SSG).

However, the people accused of smuggling are from the border Atmeh area, which is administratively affiliated to the Salvation Government. Such a border town suffers from the consequences of the deteriorating living situation and the consequences of the irrational economic decisions, which prompt them to find their own ways to survive, including smuggling goods and staples to the Salvation Government’s areas.

Since 2017, the Syrian north, which is controlled by the opposition factions that rose against the Syrian regime, has turned into two semi-states, with the Salvation Government controlling the city of Idlib and the Interim Government controlling the northern Aleppo countryside.

The position of control imposed internal borders between the two ‘states’ to organize the passage for goods and people, following economic and military decisions that formulate the movement between the two regions, as well as the conditions for movement to areas of the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES) in the northeastern region, and the regime-controlled areas.

The incident of the killing of Fatima al-Hamid highlighted the reality of borders separating opposition-controlled areas in northern Syria, which turned the region into “sub-states,” each with its own economic decisions.

In this special extended article, Enab Baladi is trying to draw attention to the state of service and institutional division in the two regions, focusing on the absence of coordination between the Interim and the Salvation governments and the outcomes and impacts on the residents of both areas.

Customs regulations define smuggling as bringing in or attempting to bring goods into the country, removing it, or attempting to remove it illegally or by fraud.

This takes place across the territorial borders of the state, which is a way to preserve its wealth and control the movement of goods and people to and from each country, which prompts the government to impose control over its borders.

In the Syrian case, “smuggling,” as described by the de facto authorities, takes place through internal administrative borders drawn by the military and political changes in the region and managed by two de facto governments with their military wings, the Syrian National Army (SNA) and Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS).

The two governments manage their areas economically with close systems and decisions in the part related to economic and commercial dealings with the Turkish neighbor, but without coordination between them, and they differ in naming these areas, as the Salvation Government considers the “liberated” areas to be the areas under their influence in Idlib, parts of the western countryside of Aleppo and parts from the countryside of coastal Latakia region, and the al-Ghab Plain northwest of Hama governorate.

Whereas the Interim Government calls the “liberated” areas the areas of military operations in cooperation with Turkey, which are “Olive Branch,” “Euphrates Shield,” and “Peace Spring.”

Security preparations at the Abu al-Zandin crossing in the countryside of Aleppo, which connects with the areas controlled by the Syrian regime – 18 March 2019 (Enab Baladi)

The killing of the young woman under the pretext of “smuggling” and the subsequent protests against Hayat Tahrir al-Sham in protest of its economic policy in the region were not the only incidents that lit up the issue of the HTS’ handling of smuggling between the areas of the Interim Government and the Salvation Government.

This incident was preceded by the closure of the al-Ghazawiya crossing by Tahrir al-Sham, halting fuel shipments between the Turkish-backed National Army areas in northern Aleppo countryside and Tahrir al-Sham areas of control in Idlib region and the western countryside of Aleppo. The closure led to the suspension of the Tarhin refinery’s operations in October 2021.

This step was considered by Hassan Ghanem, the owner of one of the domestic refineries, as an attempt by the HTS to exclude its competitors in the field and to compel civilians in its areas of influence to buy European fuel that it imported through Turkey by stopping the entry of refined fuels, which are considered desirable for the population due to its low price.

Agricultural products also have a share of the HTS decisions that prevented, in August 2021, the entry of cars loaded with the pepper crop at the Deir Ballout checkpoint linking Idlib and the northern and western countryside of Aleppo, to allow car owners to enter peppers with ten US dollars of tax for each ton, which in turn increased prices for consumers.

In September 2021, HTS faced condemnations and anger from locals for detaining and photographing three children on charges of smuggling cigarettes under their clothes, at one of the checkpoints in the village of Atmeh in the northern countryside of Idlib, at a time when economic reports speak of the suffering of an unprecedented number of children in Syria from high rates of malnutrition, due to the deteriorating economic conditions.

According to the Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR), two of the children are orphaned brothers, and the third is the breadwinner of his family, and they are from Jozef village, south of Idlib.

With the spread of the sugar crisis in Idlib during the past few weeks, and the delay in the arrival of supplies and the high price of it, and its loss from the market, social media was abuzz with pictures of civilians transporting sugar on their motorbikes between agricultural lands from “the State of the National Army to the State of Tahrir al-Sham,” according to citizens’ comments on these photos.

On 9 March, the Deir Ballout crossing, which is managed by the Salvation Government, imposed ten US dollars in tax on each ton of sugar entering from the Afrin region to Idlib and allowed civilians to enter only 5 kilograms.

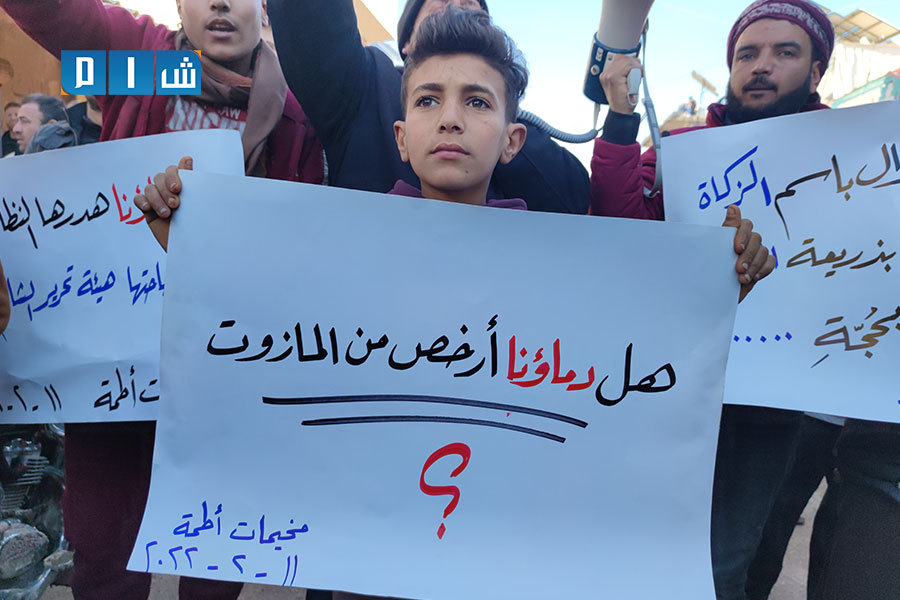

A demonstration in Atmeh camp denouncing the shooting of a woman at the Atmeh-Deir Ballout crossing – Idlib, 11 February 2022 ( Shaam Network)

Enab Baladi surveyed the views of people in Idlib in a video poll. Some considered that the people are the ones who are affected by the decisions of the de facto authorities, while merchants benefit from those decisions at the same time.

The ways to get rid of the adverse effects of these decisions are summarized by removing the crossings separating the “Liberated Areas,” which reduce the commercial movement and the transit of goods in both directions, in addition to suspending the taxes, which traders use as an excuse while setting prices.

One of the people in the poll seemed hesitant when asked about the party that benefits from those decisions in his opinion, while another man considered that the de facto authorities are the beneficiary of the decisions they issue, especially those related to the economy and the movement of the crossings, pointing out at the same time, that northern Syria is a “liberated area, not a pawned area for people who enslave people.”

According to another poll by Enab Baladi in the countryside of Aleppo, the opinions of the people surveyed coincided with the views of the people in Idlib, as they considered that the beneficiaries of the division in the first place are the merchants and those who carry out the transport and smuggling of goods between the two regions.

Each region seeks to establish its own state and center of influence, which involves restricting security concerns.

The residents pointed out the lack of understanding between the two sides regarding the issue of identification papers, which negatively affects people’s interests, in reference to the issue of car number plates (preventing a car with a number plate from entering the area from another area), and the failure to recognize identity documents issued by local councils in Aleppo countryside in areas under the Salvation Government’s control, considering that the regime is the beneficiary of these obstacles. Others considered that what is happening in the north is a reflection of the absence of regional understandings between the countries affecting the Syrian issue.

As for ways to bridge the rift between the two sides, the people believe that unifying the “Liberated Area” under one leadership and administration is the best way to turn the north into “one state” and not “multiple states,” while one of the surveyed thinks that the solution is only by unifying the “two states.”

Trucks carrying humanitarian aid provided by the World Food Programme (WFP) to northern Syria – 9 December 2021 (Izz al-Din al-Qasim/Twitter)

The Salvation Government prevents the entry of many foodstuffs such as vegetables and fruits, especially fuels, from the areas of the National Army, on the pretext that these areas were engaged in “smuggling and fraud” in the matter of diesel, which causes great harm to the beneficiaries of the substance from the general population of the north under the influence of Tahrir al-Sham.

This leads to the absence of competition and the monopoly of some commercial companies, which are accused of being affiliated with Tahrir al-Sham, on the trade of fuels and other materials, which leads to setting hard-to-break prices.

Meanwhile, the Interim Government does not recognize the crossings between its areas of control and Idlib and considers citizens of the north as one people regardless of their place of residence, according to what was stated by the SIG’s Minister of Economy, Abdulhakim al-Masri.

Al-Masri told Enab Baladi that the “other party” prevents the entry of some materials from the areas of Aleppo countryside to its areas of control, and also prevents the removal of some materials from its areas of control to the Aleppo countryside, stressing that there is absolutely no coordination between the two “governments” on any level.

However, indirectly, when the Interim Government sets import and export duties, the Salvation Government looks at them and takes it as an example to set its fees in proportion to it so that the difference is not huge.

The minister attributed the lack of coordination between the “Interim” and Salvation” regions by saying “there is nothing in common that calls for coordination,” without mentioning additional details about the reasons for the lack of coordination.

To clarify this issue and its impact on the people in the area, Enab Baladi contacted the Salvation Government, but it did not receive a response until the time this report was prepared.

In an opinion poll conducted by Enab Baladi on its website, 57 percent of the 166 participants considered that the de facto authorities are the beneficiaries of achieving an institutional division between the Idlib and rural Aleppo regions, while 43 percent of the respondents believe that influential countries in the Syrian file are benefiting from this division.

This lack of coordination raises questions about its causes and the interests of the two governments in strengthening the institutional division in various sectors between them, which is reflected on the citizens residing in the region.

Firas Shabo, a Ph.D. researcher and professor of financial and banking sciences confirmed to Enab Baladi that there are parties that have goals in perpetuating and stabilizing the reality of the lack of agreement between the two “governments” on what it is to serve their interests.

Periods of crises and stability are always accompanied by the presence of some beneficiaries, whether individuals, entities, or “militias” controlling the region.

Regarding the crossings between the “Salvation” and “Interim” areas of control, Shabo explained that these crossings generate funds worth millions of dollars daily, and thus those who manage them get huge sums of money as a result of their presence, noting that their continuation may be beneficial to certain people or entities only, not for the community or the economy of the two regions.

Shabo believes that the reason for the lack of coordination between the “Salvation” and “Interim” governments is due to an “ideological” conflict rather than an economic conflict resulting from one of them not accepting the other, but it has economic repercussions.

Both “governments” do not have effective institutions in the various sectors, considering that they are nothing but “business facilitation offices” with an executive mission, in the absence of any planning authority for each of them.

The relationship between the two “governments” is characterized by “personalization” and “individual interests” away from the interests of citizens and the public sector, according to Shabo, assuring that the cause of the conflict between the two parties may be due to the conflict of international parties controlling each party.

Members of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) during a search of cars at the Darat Izza-al-Ghazawiya crossing (Ibaa Agency)

The political and military entities and entities controlling the areas outside the control of the Syrian regime in northwestern Syria are diverse, making them “de facto” authorities separated by “boundaries,” and they remained not involved in understandings regulating the mechanism of action and movement between the two neighboring regions of Idlib and Aleppo countryside.

This mixture actually constitutes the reality of the north, which suffers despite the “overcrowding of officials,” an unstable economic, security, and social reality through two governments controlled by the Syrian National Army and Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, in addition to military banners with different slogans, colors, ideology and dependency, and local councils.

The purpose of forming the Salvation Government in the areas controlled by Tahrir al-Sham on 2 November 2017 was to extend its administrative influence and control over the joints of life in Idlib governorate, the northern Hama countryside, and part of the western countryside of Aleppo, following an agreement, after 18 months of its formation, between Hayat Tahrir al-Sham and The National Liberation Front (NLF), leading to making the entire region affiliated with the Salvation Government.

The Salvation Government, consisting of 11 ministerial portfolios, emerged in light of complexities, internal tensions, and the international presence of Idlib in international political discourses, the conflict of which indicates the instability of the region, in addition to the indirect control of Tahrir al-Sham over it.

Observers believe that the formation of the government came due to the need for a “civilian body” to administer the region, but it is managed by a military hand by the leader of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, Abu Mohammed al-Golani, to extend his group’s authority over the region in a convincing manner.

The Civil Administration for Services affiliated to Tahrir al-Sham was handed over to the Salvation Government in terms of water, electricity, transportation, and others.

Since its establishment, the Salvation Government began imposing its control on 12 December 2017 by closing the offices of the Syrian Interim Government and removing them from its areas of control within a time limit that did not exceed 72 hours.

The government of the Syrian National Coalition (SNC) responded to the matter and transferred its activities, the last of which was on 22 December of the same year, when it moved the headquarters of the Free Aleppo University from Idlib to the western countryside of Aleppo, after the Salvation Government appointed a new president to the university.

In light of accusations against the “Salvation” of its affiliation with Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, it suddenly adopted, and in accordance with a decision issued by the Constituent Assembly, a new flag for Idlib, of four colors, that mixes the flag of the Syrian revolution with the Islamic banner. This was met with angry reactions. This step was considered an attempt to obliterate the features of the revolution and its flag that was raised at the beginning of the revolution while leading figures from within Tahrir al-Sham considered it a retreat from Islamic principles.

Tahrir al-Sham stated, through a video release on its fourth anniversary of founding on 28 January 2020, that a number of “elite figures” in northwestern Syria took the initiative to form the Salvation Government, a civilian government “to arrange the affairs of the liberated north, and provide what they can for civilians,” which has entered its fifth session.

The release stated that Tahrir al-Sham fully supports the Salvation Government for its civil services.

Prior to the formation of this government, Idlib was under the control of the Syrian Interim Government, which was formed about two years after the outbreak of the Syrian revolution, specifically in March of 2013, with the support of the Syrian opposition’s National Coalition, along with other opponents.

Ghassan Hito was the first head of the Interim Government of the “Coalition,” whose support at that time was limited to the Syrian Business Forum and its head, Moustafa al-Sabbagh, the former Secretary-General of the “Coalition.”

But things changed in September of the same year when it changed its formation and was headed by Dr. Ahmed Tohme until May 2016, then it was headed by Dr. Jawad Abu Hatab, from May 2016 to March 2019.

Abdulrahman Moustafa is currently the head of the Syrian Interim Government since June 2019.

The Interim Government owns a military wing represented by the Syrian National Army, whose formation was announced in October 2019, in the city of Şanlıurfa, southern Turkey, by a group of military leaders in the Syrian opposition, led by the Minister of Defense in the Syrian Interim Government and the Chief of Staff at the time, Salim Idris.

This Turkish-backed military body includes the National Army, which was formed in December 2017, from three corps, each comprising a group of divisions and brigades, as well as the National Liberation Front, which includes 11 factions of the former Free Syrian Army (FSA) in Idlib governorate in May 2018.

This diversity in military and civil administrations was reflected in the social climate, creating different patterns of life, which may conflict within one geographical area transformed by divisions into two regions of control.

The opposition-controlled areas and the regime-controlled areas are intertwined with different crossings, and the opposition-controlled areas have internal crossings between them.

The two areas are linked by two internal crossings, the first of which is the Darat Izza- al-Ghazawiya crossing, also known as the Darat Izza road, which connects the town of Darat Izza in the western countryside of Aleppo to the Afrin region in the eastern countryside of Aleppo.

The village of al-Ghazawiya is located north of Darat Izza in the archaeological area of Deir Semaan, which is also an elevated area overlooking the Afrin road and the western countryside of Aleppo.

The second crossing is Deir Ballout–Atmeh, connecting the northern Idlib countryside with the northern and western Aleppo countryside. This crossing is located on the road between Deir Ballut village and Atmeh area, north of Idlib, which is affiliated with the Salvation Government.

The crossings are supervised by forces affiliated with Tahrir al-Sham and the General Security Agency operating in Idlib, which denies any connection with them.

These internal crossings are considered of a high degree of importance in terms of allowing the entry and exit of commercial goods, the movement of civilians, and other procedures.

Tahrir al-Sham tightened its control over the crossings with the National Army areas during the military action it started against the Nour al-Din al-Zenki military group in early 2019, during which it was able to control the entire western countryside of Aleppo.

The Tahrir al-Sham’s closure of crossings with the areas controlled by the National Army was attributed to several reasons, the most prominent of which is the fear of the passage of cells belonging to the Islamic State (IS) group to the areas it controls and information that “batches of IS elements were heading to Idlib from SDF areas,” besides other reasons, such as organizational measures to control the transit movement, secure the road, and the spread of Covid-19.

The Abu al-Zandin crossing, east of the town of al-Bab in the eastern countryside of Aleppo, is a commercial and humanitarian crossing that separates between areas of the Interim Government and the Syrian regime.

The crossing, which is located near the village of al-Shamawiya, which is under the control of the regime, is considered as one of the contact areas between the National Army and the SDF and regime forces that control the eastern side of the Euphrates River. The sporadic skirmishes that occur from time to time cause security tensions in the region and affect the crossing.

Abu al-Zandin is the first crossing that was opened between the areas of the northern and eastern countryside of Aleppo, which are under Turkish administration and the regime’s areas, and through which several prisoner exchange operations were conducted between the National Army and the regime forces, under Turkish-Russian sponsorship and under the supervision of the United Nations and the International Red Cross.

The SDF-controlled areas, which constitute the military wing of the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES), are linked to the National Army’s control areas with several crossings: the al-Hamran commercial crossing near the city of Jarablus used to transport goods only. It connects the northern countryside of Aleppo with Manbij region in the eastern countryside. It is run by the Levant Front, a key faction of the National Army.

As well as the Awn al-Dadat commercial crossing in the southern countryside of Jarablus city, separating the Interim Government and SDF areas, in addition to the al-Halwanji humanitarian crossing, about seven kilometers from the Awn al-Dadat crossing in the southern countryside of Jarablus.

These crossings are under the control of the National Army, whether with the regime or with the SDF, and they are closed to commercial and civilian traffic.

The National Army is accused of passing and smuggling some materials and people through these crossings in exchange for sums, but it denies such allegations.

The areas under the control of the Salvation Government, which include Idlib governorate and part of the western countryside of Aleppo, Latakia countryside, and al-Ghab Plain, northwest of Hama, are linked to the areas controlled by the Syrian regime through the Miznaz-Maarat al-Naasan crossing between the town of Maarat al-Naasan, which is located in the town of Maarat al-Naasan in the eastern Idlib countryside.

It is under Tahrir al-Sham’s control, while the regime forces control the town of Miznaz, west of Aleppo. The crossing is used to bring in relief aid from the United Nations only, under the name of “cross-lines aid,” coming from its warehouses in regime-controlled areas.

The second crossing, the Trinbeh-Saraqib crossing in the eastern countryside of Idlib, also links their areas of control. Trinbeh is the last point of control of the regime forces, and al-Nayrab is the first opposition-controlled area in eastern Idlib, and they are located near the international highway Aleppo-Latakia, known as (M4).

These two crossings are closed, and the Tahrir al-Sham group and its affiliates are accused of smuggling civilians under the name of a “military line,” but it denies this allegation.

Arguments about opening internal crossings, which connect the areas controlled by the Syrian opposition factions in the north and the regime areas, are always accompanied by popular anger and resentment and rejection of this step because opening the crossings, according to some, means dealing with the regime politically and revitalizing its economy, neglecting that it may benefit northern Syria economically.

The expert Dr. Firas Shabo pointed to Enab Baladi the illegal and informal entry of goods between all internal crossings despite the denials of official authorities due to “substantial” returns that the ones who manage crossings obtain. “Opening these crossings would be in their interest as well,” he added.

In 2020, Tahrir al-Sham sought to open the Miznaz crossing to cross commercial convoys between it and the regime, but it did not succeed after facing popular anger, protests, and demonstrations in the area near the crossing.

The National Army factions also exchange accusations among themselves of opening the crossings to pass cars and trucks carrying foodstuffs and fuel to the regime areas and the Autonomous Administration’s territories, which is matched by the factions’ denial of any operation to open or pass materials from those crossings.

Shabo explained that opening the crossings between the opposition and the regime has its benefits, as each region possesses some capabilities and competitive advantages, industrial, production, agricultural, or even in terms of fuel.

The presence of crossings and the trade exchange through them eases the economic suffocation, and imposing royalties or taxes and customs, as is rumored on transport operations, and thus would be a source of income for both parties, according to Shabo.

Opening the crossings and exchanging products between these regions contributes to reviving the economic situation, according to Shabo, who explained that trade which requires securing markets for trade exchange and obtaining primary resources, contributes to economic recovery.

The SDF-controlled areas are somewhat characterized by the availability of wheat and fuel, the opposition-held areas have food, professional and manual products, commodities, and various imported goods, and the regime-controlled areas may have some industrial and production products.

The researcher Shabo explained that the economic recovery is reflected in the development of small projects, improving citizens’ income, and creating job opportunities, thus alleviating the “miserable” economic reality and somewhat contributing to limiting the exaggerated price hike in these areas, mainly due to the lack of materials.

The existence of crossings is a healthy and natural condition to revitalize the economic situation of all parties, according to Shabo, and what Syrian citizens are experiencing needs to be calmed down. Even the UN recently talked about re-discussing the sanctions on Syria due to the economic situation that citizens experience inside Syria.

The Syrian people in various regions live under the yoke of deteriorating living conditions, poor economic conditions, and a rise in prices with the absence of the ability to control them in light of the low purchasing power of citizens and the low level of income and wages.

The positive aspects of opening the crossings between the regime and the opposition do not deny the existence of negative aspects, which Shabo summarized through the regime’s benefiting from these resources, as it is subject to great economic pressure, and opening any crossing is in its interest.

Dr. Shabo believes that opening the crossings contributes to strengthening the regime’s ability to finance its operations from foreign exchange, as it can benefit from the US dollars in opposition areas while it deals in Syrian pounds in areas under its control.

Abdulhakim al-Masri, Minister of Economy in the Interim Government, explained to Enab Baladi in a previous talk that opening the crossings with the regime would allow it to pull US dollars from the northern regions by all means and methods through affiliated merchants, who can buy dollars at any price, in a process that may lead to the depletion of the dollar.

The regime will instead pump the ‘frozen’ dollar to the north, which is banknotes that were officially printed but whose serial numbers were suspended and their balances frozen in banks located in war zones or because of thefts. These banknotes are offered at prices ranging between half and two-thirds of their real value, and they can only be identified by official financial institutions, according to al-Masri.

Syrian National Army fighters at the Abu al-Zandin crossing during a prisoner swap operation with the regime forces – 16 December 2021 (Siraj Mohammed/Enab Baladi)

The most important risks of opening the crossings with the regime’s areas are drug smuggling into northern Syria, as the regime leads organized and massive smuggling operations to all neighboring countries, so the regime will not hesitate to bring it into the northern regions in light of the limited capabilities of detecting hidden drugs in many ways.

Since 2011, Syria has become a major market or transit country for suspected drug-trafficking activities around the world, through land, sea, or even air routes.

Syria is also considered a drug state because it contains two main types of drugs, which are “Cannabis” and “Captagon.” These activities include the production, distribution, and export of narcotic substances. The regime also uses the border crossings that it controls as a way to pass deals for smuggling narcotic pills to other countries.

The minister also indicated that opening the crossings would give the regime an opportunity to export surplus goods to the northern regions, such as clothes that are already being manufactured in the northern region’s factories and some vegetables and fruits that farmers have difficulty disposing of.

The regime will also benefit from car fees, as it charges a fee for all vehicles entering its areas of up to 8000 US dollars for cars loaded with oil and a fee for cars entering the Syrian north.

The opposition armed factions were condemned by local activists for crossings unlocking attempts with the regime-controlled areas or the Kurdish-led SDF, accusing Tahrir al-Sham of “treason and compromising.”

The denunciations came due to the opening of crossings linking opposition areas with regime areas for relief and humanitarian aid trucks of the UN World Food Programme (WFP), protecting the aid convoy, and for allocating military vehicles and a large number of personnel to secure aid delivery to the warehouses in Idlib.

Factions affiliated with the Syrian National Army are also accused of bringing in and removing materials and products from and to the regime’s areas and accusations of smuggling collaborators or members of the regime in return for sums through the Abu al-Zandin crossing, but the factions deny these charges.

These fears emerged through a hashtag launched by activists on social media in March 2021, and some of them considered the opening of the crossings to be “a betrayal of the blood of the revolution’s martyrs.”

if you think the article contain wrong information or you have additional details Send Correction