Hussam al-Mahmoud | Jana al-Issa | Hassan Ibrahim

The 11th anniversary of the first shout for freedom that was heard throughout the war-torn country has just come. Syrians commemorated the awaited victory outside the regime-controlled areas and even within some of it, sweeping the social media with memories of the early days when chants of freedom and dignity were rumbling in all throats.

Such a desired freedom deviated from the teachings of the slogans of the ruling Baath Party and deviated from its verbal and theoretical context into practice. The Syrian regime received freedom seekers with tanks in the streets and planes in the sky, detainees in the darkness of cells, and millions of displaced people inside and outside the borders.

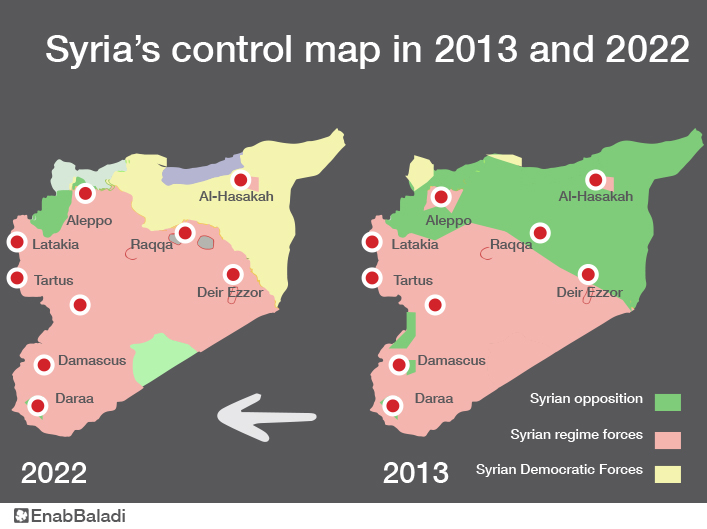

With a wide sweep at the beginning of the revolution for the Syrian armed opposition, which was formed for a purpose it did not achieve, the regime’s leverage and influence shrunk, on geography on the one hand, and before the international community on the other, until the Russian intervention came in late 2015 and completely reversed the verse.

Russia took advantage of the weakness of the opposition that had multiplied politically and militarily, shadowing over the reality of the revolution, so the celebrations were present on the 15th of March, but victory was absent.

In this special file, Enab Baladi discusses with a group of political and military experts, thinkers, and intellectuals the factors that have drained the revolution and weakened it in the material sense.

Enab Baladi also explains with the interviewees what the Syrian revolution needs today and what it has lost over the past years, focusing on the strength factors and the remaining gains of the Syrian revolution.

One revolution, No political pillars

Politics is the art of managing public affairs or the art of managing power relations in society as it is defined in the special sense, which means that the political action, whether individual or collective, such as the Syrian revolution, requires political management and theoretical framing, stemming from the generality of political action, and allocating it within political values, in order to be represented to the public within work programs, with the aim of institutionalizing it and transforming it into principles or laws that frame political action and govern its standards.

According to journalist Maher Masoud, the Syrian revolution may be the most important political act that Syrians have done during the past half-century. But on the other hand, what the revolution has missed most is politics, he said in a piece titled “Revolution without Politics.”

Residents of Idlib city commemorate the Syrian revolution’s 11th anniversary – 15 March 2022 (Enab Baladi/Anas al-Khouli)

The platforms and political bodies, despite their large number, were not able to achieve what Syrians called for (toppling the regime) since March 2011, when the people’s confidence in them and any change that might come from their hand became “almost non-existent” as a result of the confusion they suffered and failure to achieve what those who rebelled against tyranny aspired to.

In a situation similar to the military situation, the Syrian revolution passed through 11 years in several stages at the level of the political opposition that gathered to establish the first political movement three months after the start of the peaceful protests, on 30 June 2011. At that time, several political parties and opposition figures announced the establishment of the National Coordination Body for Democratic Change to be a political alliance that brings together the “internal opposition.”

After meetings and talks attended by some members of the Coordination Body, a group of opposition figures from Istanbul announced, on 2 November 2011, the establishment of the Syrian National Council as the first political body considered a representative of the Syrian revolution, both internally and internationally, headed by the Syrian intellectual and opposition figure Burhan Ghalioun. The Coordination Body did not join the council.

In 2012, the National Council witnessed several withdrawals of parties and persons from it, and the formation of parties separated from it, for several reasons, including internal differences between the parties and criticism of it due to its “inability and failure to work.”

The demands were repeated to unify the opposition, which, despite many political bodies and rounds, failed to achieve tangible progress to achieve part of the revolution’s demands, through the National Coalition for Syrian Revolutionary and Opposition Forces, to the “Cairo” and “Moscow” platforms, the Syrian High Negotiations Committee, and the peace talks of Geneva, Astana, and Sochi, and last the Constitutional Committee.

Politics and Uprising

Burhan Ghalioun, a professor at the French Sorbonne University and the former head of the Syrian National Council, says that the revolution needs political leadership that unifies the vision to implement its goals within a clear strategy, and this is what it did not possess, as the political leaders born simultaneously with it sought to create multiple platforms.

In an interview with Enab Baladi, Ghalioun said the Syrian uprising belongs to the green revolutions, as it is both a spontaneous and peaceful popular revolution since it did not possess a professional revolutionary party nor a global ideological vocation that would secure international support from the forces loyal to it.

The Syrian thinker emphasized that the revolution did not have political tools, but rather the general and comprehensive uprising was its tool and its essence, considering that the intersection of many regional and international interests with the existing regime worked to turn the revolution into a long-term war, at the expense of the revolution and the people.

Subordination, Loss of tools

Louay Safi, another Syrian thinker and academic, believes that the urgent need now is to unify the Syrian voice calling for change at home and abroad in order to bridge the clear gap between the political elites and the Syrian street to disregard opposition leaders.

In his interview with Enab Baladi, Safi explained that the revolution has political tools that have lost some of them for many reasons, and the rest cannot be used without certain conditions.

“The revolution has lost the internal cohesion generated by the feeling of unity of concern and purpose, as well as the international respect imposed by the sacrifices of the Syrians, their insistence on rejecting tyranny, and their willingness to pay the price of freedom and dignity,” he said.

The thinker attributed the reasons for the revolution’s loss of these tools that it previously owned to the conflict between the military leaders and the quarrels of politicians, which contributed to changing the revolutionary image, leading to the stagnation of the political file and the dependence of the institutions of the revolution and the opposition on the supporting countries.

According to Safi, capabilities must be unified, the institutional structure restructured, and a specific national project developed in order to take advantage of the opposition’s current political tools in order to preserve the continuity of the revolution.

At the same time, he criticized the “strange insistence” on waiting for international moves and ignoring the importance of communicating with popular forces and linking civil and political institutions into a coherent structure.

The movements of the Syrian opposition today, after the revolution lost the most important tools to achieve its demands, raise questions about the extent to which it possesses pressure cards to move the Syrian file, in light of the absence of the actual measures attributed to it and the decline of its military control on the ground.

Professor Safi considers owning the land important, but the most important is having the vision, the plan, and the structure, explaining that “an enemy can rob a land for a while, but he will not be able to hold it if the owners of that land have the clear vision to liberate their land.”

He also stressed that the political opposition does not have pressure tools to move the Syrian file, after the internationalization of the Syrian issue, due to its weak relationship with its popular bases.

“For the restoration of the initiative by the political opposition, there are necessary conditions, such as restoring the relationship with the Syrians at home and in the diaspora, and developing a plan and an appropriate structure to deal with the challenge,” he concluded.

Opposition legitimacy is the people

The transformation of the Syrian issue into a mere file on the international negotiating and bargaining table indicates that there is no longer any opposition, resistance, popular or national movement, says the former head of the National Council.

Ghalioun justifies his vision by saying that the opposition or the national movement does not submit a file or complaint before the international diplomatic and political circles but works on the ground with the people to achieve its goals.

He added that to the extent of the strength, credibility, and efficiency of this work, the case turns from a file or complaint that no one pays attention to, to a challenge to the forces that want to bury it or evade their responsibilities towards it.

The Sorbonne professor stressed that the Syrian opposition does not have any means of influence except to the extent of its works on the ground and coalesces with the people to organize their resistance and various activities, explaining that “begging on the threshold of international diplomacy does not produce opposition and does not raise a central issue.”

The Syrian opposition delegation meets the UN Special Envoy for Syria Geir Pedersen – November 2019 (UN)

“Power is a booty,” opposition will not unite

The various political platforms that speak in the name of the revolution have done a lot of harm to the revolution, as the thirst of some Syrians to start political work before the completion of the political transition process, and their competition for political power that is still fragile before the success of the revolution has resulted in damages suffered by the revolution. Internal discord made it easy to control the Syrian political scene from the outside,” according to Dr. Louay Safi.

The academic believes that the most annoying obstacles to unifying the opposition are manifested in the Syrian political culture, which does not link political action to the moral and national responsibility of the individual and considers access to power merely as an opportunity to spoil.

In addition to the absence of the necessary efforts to build confidence and adherence to the principles and rules required for public work and joint action, Safi added.

In turn, Dr. Burhan Ghalioun emphasized that unifying the opposition is possible through work only and moving from “personalization” issues to stripping them of personal emotions.

What explains the division of the political opposition today is its “inability to overcome differences, of which 90 percent are personal and not political,” said Ghalioun.

Can the Syrian opposition be recovered or revived?

Professor Ghalioun did not agree with the term “reviving the opposition,” explaining that the more correct question is how to build an opposition.

He attributed this to the inability to revive a weak, aging, or absent opposition, which has turned into a “rotting corpse” in some of its “so-called institutions.”

Ghalioun assured that the true opposition is built through practice, pointing to the need for an emotional awakening, a pause for reflection, a serious review, and a better sense of responsibility.

According to Dr. Safi, the Syrian political opposition needs to build civil institutions and consolidate street ranks in order to move from the waiting mode to generating solutions and taking national initiatives to reach them.

The Syrian intellectual stressed the need to build political awareness so that every Syrian feels that it is his duty to press on his political and military leaders, with the aim of prioritizing the public interest over the private rather than sitting in the onlookers’ seats.

It is necessary for someone who assumes political responsibility to find someone who will question him on a daily basis about his achievements and contributions to make them a basis for his continuation in his leadership role.

“This is what has not happened in Syrian politics for a long time,” according to Safi.

Has the revolution lost its military compass?

Months after the pro-democracy demonstrations calling for the overthrow of Bashar al-Assad’s regime, local groups emerged with light weapons to protect civilians within the revolting areas and cities from regime forces, security services, and thugs militants (Shabiha) who confronted the peaceful demonstrations by crackdowns, live bullets, arrests, and major military assaults.

When the military picture took the full shape through armed factions with an organized character, the areas of military action expanded, and many areas escaped the regime’s grip, which used “excessive” force to subdue it until armed action became the mainstay of confronting the regime forces and allied militias at the time.

With the intervention of the regime’s allies (Russia, Iran, and Hezbollah), the opposition’s control began to retreat on the ground and the areas that it controlled decreased.

The fire of “revolutionary military action” has subsided since the beginning of 2020, except for “bashful” attempts to respond to the bombing of the regime and its allies.

The factions were subjected to criticism and accusations of subordination and preoccupation with personal interests, which caused the discontent of the people who appealed to open battles against the Syrian regime forces and to restore the lands and properties of the IDPs and refugees.

Fighters of the Syrian National Army during military exercises in the eastern countryside of Aleppo city – 18 February 2022 (Azm Command Room/ Twitter)

Is revolution just a rifle?The words of revolutionary and revolution were associated with armed action in Syria, and it remained stuck and attached in the minds of Syrians with the rifle. The military expert Colonel Fayez al-Asmar believes in an interview with Enab Baladi that the revolution cannot be reduced to military action, for revolutions often start peaceful, and what drives them to armed action is the intransigence of repressive authoritarian regimes and their adherence to power. In turn, military analyst Tariq Haj Bakri thinks that the revolution is not primarily military. Revolutions are beliefs and ideas, not militarization. Haj Bakri clarified that the revolution includes all aspects of life, the most important of which is changing ideas, as it is a social, cultural, economic, and liberation revolution. The military endeavor is a tool for change and to achieve the goals of the revolution, which is not militarization, but rather to make Syria a nation that meets the demands of all people, Haj Bakri said. |

Battles mills do not grind

The military action in northwestern Syria since the Moscow agreement in March 2020 has been limited to “timid” skirmishes, such as sniping soldiers or targeting places where the Assad forces are stationed in areas within the goal of the opposition factions, in exchange for almost daily bombing by the regime and allied militias, causing human and material damage.

The Moscow agreement stipulated a ceasefire in Idlib along the engagement line between the Russia-backed regime forces and the armed opposition.

Colonel Fayez al-Asmar considers that the weapon is “subordinated to others,” and the calm ground is the proof.

“The fields and fronts have been muted for years, except for the regime’s missiles and the strikes of Russian aviation,” he added.

The factions do not move because of subordination and the leadership’s preoccupation with their personal interests and the collection of money and trade, according to al-Asmar.

Some opposition factions have been accused of complacency and of inventing honorary positions and ceremonies of a financial or service nature.

They are also accused of smuggling materials and people through the crossings, and some of them were convicted of these charges.

Major Haj Bakri attributes the state of military stillness to losing the decision, considering that the current calmness is not with an internal will.

Crowded flags, Conflict of interest

Many banners and numerous military factions, as well as many names, surfaced, despite the various rifles aimed at the overthrow of the regime and its allies and despite the presence of two military bodies in northwestern Syria outside the regime’s control.

The first is the 3-year-old Turkish-backed Syrian National Army (SNA), which included many factions that fought since the beginning of the revolution, and Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), which began its military operation in 2011 with several different names, to be known by its current name since 28 January 2017.

The multiplicity of factions’ banners raised questions about the obstacles to uniting the ranks, which Colonel al-Asmar attributed to the “ego” and the rampant gangs within the factions, whose interests and livelihood will be ended by the army’s arrival to institutionalization and discipline.

While Maj. Haj Bakri stressed that the multiplicity of flags came as a result of the countries’ struggle and war among themselves on Syrian lands and with Syrian hands, and the unification of these flags is linked to international resolutions and the positions of countries, whether the US, Russia, or Turkey.

It is also linked to the international decision to oust the Assad regime. The armed factions cannot be liberated before the removal of the regime, which will then pave the way for the unification of the factions and the formation of a truly national army that is an alternative to the military structure of the regime and has an impact on the Syrian ground in full.

Talking about the revolution’s lack of opening battles against the regime, opened the door to the military tools that the revolution lost today, the military expert Haj Bakri explains that these tools of gear and equipment are still present and have become better and more capable of opening battles and achieving victory, but they are limited and prohibited from operating.

Deadlock continues

The state of military calmness has reinforced the Syrians’ fears and concerns about the situation the war-ravaged country will be or is heading to.

In parallel with the Russian war on Ukraine, which has taken with it all of the international concern towards the door of suffering that has just opened, without closing the first door in Syria in the first place, but cordoning off the Syrian file and reducing its regional or international risks on the international priorities agenda.

Haj Bakri assumes that the current circumstances are going to preserve the “paralyzed” situation, with the possibility of distributing areas of influence in Syria to achieve political and perhaps economic and geostrategic gains in the eastern Mediterranean region, which is considered a strategically important scene globally.

The military analyst added that the situation in Syria has turned into a state conflict, not just a revolution against an unjust regime.

Militarily, What does the revolution need?

The most prominent thing that the revolution needs today, in the opinion of Colonel Fayez al-Asmar, is the establishment of a specialized military academic institution with firm leadership in which favoritism and “utilitarian relationships” are eliminated.

Adding that the factional flags and banners must be torn apart under the revolution’s flag, in addition to establishing military courts for those who dare to prejudice the interests and principles of the revolution.

Recently, several factions and senior commanders were convicted of committing violations without the perpetrators being held accountable, and the judicial and security authorities were unable to “deliver justice.”

Maj. Haj Bakri stressed that the revolution needs to unify its positions on the political level, stemming from the internal support of influential and powerful figures who are able to prove themselves at the international level to achieve recognition of the revolution, which means political gains capable of reaching the centers of decision-makers internationally.

These tools include uniting politics and politicians because the opposition alone is unable to act in isolation from the revolutionary politicians living inside Syria, who should be united with the opposition figures outside Syria, according to Haj Bakri.

“This is the first step that must be worked on, in addition to mounting a popular pressure demanding the unification of the military factions and political positions.

All that to build a force capable of imposing the revolutionary political presence on the international and regional levels, which is what the revolution needs now,” adds the military analyst.

Two members of the General Security Service during commemorations of the 11th anniversary of the Syrian revolution in Deir Hassan town in Idlib countryside – 16 March 2022 (The Military Correspondent / Telegram)

“Political Art” for present and future

If art is a creative human activity that embodies what was, what is, or what should be, then the emergence of a state of artistic and cultural activity that accompanied the revolution to express it and its issues came as a natural response to form a complementary course of political and military struggle.

Although art broadly expresses the renaissance of nations and their civilized state, it is at the same time a means of pre-renaissance civilization, even in cases of chaos, to be a witness to the event and a writer of history without numbers and statistics hence emerged the “political art.”

The two military analysts, interviewed by Enab Baladi, agreed that the presence of the weapons, which were used to repel the regime and key allies, does not negate the need for will and determination, the desire for change, and the fighting spirit, as long as a good part of any battle is psychological warfare as well.

The various regions outside the regime’s control witnessed revolutionary celebrations and events that reminded Arab and international public opinion of the first biography of the Syrian revolution 11 years ago.

Analyst Haj Bakri assured that the most effective tool in any revolution still exists, which is the will and the burning spirit.

Generally, during conflicts, one party focuses on the attempt of one party to weaken the will of the other, which necessarily means weakening its resistance.

“But this has not happened, at least so far, in the Syrian revolution, which confirms its continuity in various ways,” Haj Bakri said.

According to a research study by the Arab Journal of Scientific Publishing, in November 2019, some artists are trying when political and humanitarian crises abound to participate in events expressing the voice and opinions of the marginalized and to defend human rights in the face of dictatorship, tyranny, and manifestations of societal injustice to express certain views on some important issues.

The revolution is carved on foreheads

Bilal al-Barghouth is a young Syrian man who has many literary works that revolve around the orbit of the Syrian revolution, which roam within its events and facts to narrate the Syrian Iliad.

He believes that a new identity for Syria has emerged with the beginning of the revolution by a case of cultural innovation through integrating Syrian lyrical folklore like “Mejanna and Ataba” and banners, murals, and caricatures.

Bilal indicated to Enab Baladi that the poem entered the line of events as well, but to a certain limited extent due to the fragmented organizational situation. Anyone who was able to deliver ideas through literature, paintings, and music, has done so through purely personal effort.

The cultural condition inside the revolutionary environment cannot be compared with the cultural situation in the regime-controlled areas, given that the regime has not presented a real cultural or intellectual identity to Syria since it came to power, and all that is presented in the media and through art and religious channels is the regime’s narrative only, according to al-Barghouth.

The revolution founded a somewhat active cultural situation, manifested by access to international forums and honors.

Also, the exhibit of images confirming and chronicling fixed moments of Syrians’ tragedy in various countries of the world, through exhibitions that drew their material from siege and bombing to present the situation to world public opinion, without neglecting the role of music and songs, a role that is not different in value and influence from all that preceded it.

The young writer draws his stories from the lives of people he actually knew, through displacement, siege, displacement, asylum, and life in exile.

He also points out the participation of literature in history, archiving the event and the stage in which the region is still living, with its mysteries that, of course, cannot be revealed, as long as there are dictatorial regimes that are still present on people’s skulls.

“This stage must have its historians who write with the pulse of the street, not with the dictates of dictatorships,” says al-Barghouth.

Tragedy is a state that remains for the Syrians, if not in their reality, then in their memory, perhaps, as long as the wounds of memory are difficult to heal, and history and documentation are here, not to take a lesson, but for the victims’ right to have their voice remain after them, al-Barghouth concluded.

Residents of al-Bab city commemorate the Syrian revolution’s 11th anniversary – 15 March 2022 (Enab Baladi)

Tool of revolt, not luxury

After taking art out of its entertainment context, artists resort to their tools to activate the audience’s imagination, create questions, and illuminate aspects and details that the individual lives without noticing their existence, in response to the demands of change and the overthrow of what is dilapidated and fragile, and other revolutionary ideas.

At this moment, art becomes a necessity and a weapon, not a luxury, as it is a weapon of another kind that contributes to the process of cultural implantation, which explains the efforts of totalitarian regimes to tame it and direct its course.

The Idlib-based artist Aziz al-Asmar has used the wreckage of buildings destroyed by the bombing of the Syrian regime and Russian airstrikes as a ground for his paintings that simulate the reality of humanitarian issues in the world as a whole.

His paintings were in solidarity with Ukraine, against racism, about Maradona’s sudden death, for Jerusalem, for the revolution and its concerns, and for the departure of Abdulbasit al-Sarout, one of the most prominent voices of pro-democracy demonstrations in the early months of the Syrian revolution.

In an interview with Enab Baladi, the Graffiti artist said that the cultural and intellectual aspect of the revolution needs more attention, development, adoption of competencies, and securing what supports its creativity, which he considers an effective weapon in undermining the regime’s slander, falsifying its allegations, and demonstrating that the Syrian revolution is an intellectual and human revolution.

“Art is a mirror that reflects people’s pain and dreams, and when it turns into cosmetics for the regime’s face, it falls morally and historically,” he says.

Al-Asmar stresses that the difference in number, capabilities, and focus between the two cases is vast when compared with the cultural situation in the regime-controlled areas. The artists of the revolution are the product of injustice and displacement, and the “revolutionary elites” of the good people are not separated from their dreams and pains, unlike the “luxury elites” who build an insulating wall between it and its surroundings.

On the role of art in splashing the image of what is happening, al-Asmar explained that art is a universal language that is understood by the recipient in any part of the world, and the drawings that deal with human sufferings and aspirations reach people regardless of race, color, and nationality.

Al-Asmar calls for the arts and cultural movement to continue to convey their messages, regardless of the challenges, whatever it may be.

|

“By drawing, we said that we are not terrorists and our revolution owns culture, morals, and a sense of humanity. The drawings are honest documentation of a history that turned the rubble of Syrian homes into illustrations in the pages of its notebooks.” Syrian Graffiti artist Aziz al-Asmar |

Art questions norms of politics

The research study issued by the Arab Journal of Scientific Publishing indicates the ability of art to create an impact on societies by challenging popular ideas, provoking new ones, and questioning established political and social standards, which makes this art a tool for desired change.

Abdulsalam al-Shebli, a young Syrian man with two poetry collections and a prose book, explained to Enab Baladi his adherence to writing under the shadow of the revolution, the extent of his adherence to writing itself.

Al-Shebli, whose short story collection “A Last Bullet in a Bad Dream” won the “Suad al-Sabah” prize for intellectual and literary creativity in the short story category, stressed that writing outside the framework of the revolution and the rights of Syrians is an idea he does not like.

Referring to the presence of the revolution in everything he has written so far, whether directly, as he did in his first poetry collection, “The Femininity of a Nation,” or in an expressive manner, as he wrote in his poetry collection “No Text Should Be Completed” or his novel “The Margins of Love and War,” and even His short story collection “A Last Bullet in a Bad Dream.”

The true function of literature is to be a voice for the oppressed who are unable to make their voice heard, according to al-Shebli, who stresses that blood, destruction, asylum, and alienation all conveyed the message of the Syrians, but where did the echo return?

if you think the article contain wrong information or you have additional details Send Correction

النسخة العربية من المقال

-

Follow us :

Most viewed

- Al-Hijri escalates against Damascus: A "radical" government

- Governor of As-Suwayda signs understanding agreement with al-Hijri: Key details unveiled

- Turkey confirms continuation of its operations in northeastern Syria

- Al-Sharaa signs draft constitutional declaration

- Al-Sharaa forms National Security Council in Syria

Residents of Idlib city commemorate the Syrian revolution’s 11th anniversary - 15 March 2022 (Alzeer Ammar)

Residents of Idlib city commemorate the Syrian revolution’s 11th anniversary - 15 March 2022 (Alzeer Ammar)

A

A

A

A

A

A

More In-Depth

More In-Depth