Caught between rigid beliefs and toxic masculinity: Women in northwestern Syria

Jana al-Issa | Diana Rahima

Women in northwestern Syria are living in a state of confusion regarding their ascribed roles in social and economic life, amid rising criticism of harassment targeting women’s personal freedoms.

Women in this part of Syria are facing many challenges, starting with security threats and not ending with restricting procedures aiming to reduce their roles and effective social presence.

The restrictions can be attributed to several factors, chiefly the absence of regulations and rules governing the treatment methods of local authorities with women and the limited understanding of the Islamic religion’s approach to women issues. Traditions and social norms tainted with patriarchy are also responsible for the unjustified restriction on women.

Some civil society organizations are working on supporting and empowering women in the northwestern region, but women there continue to be harassed by communities and authorities alike.

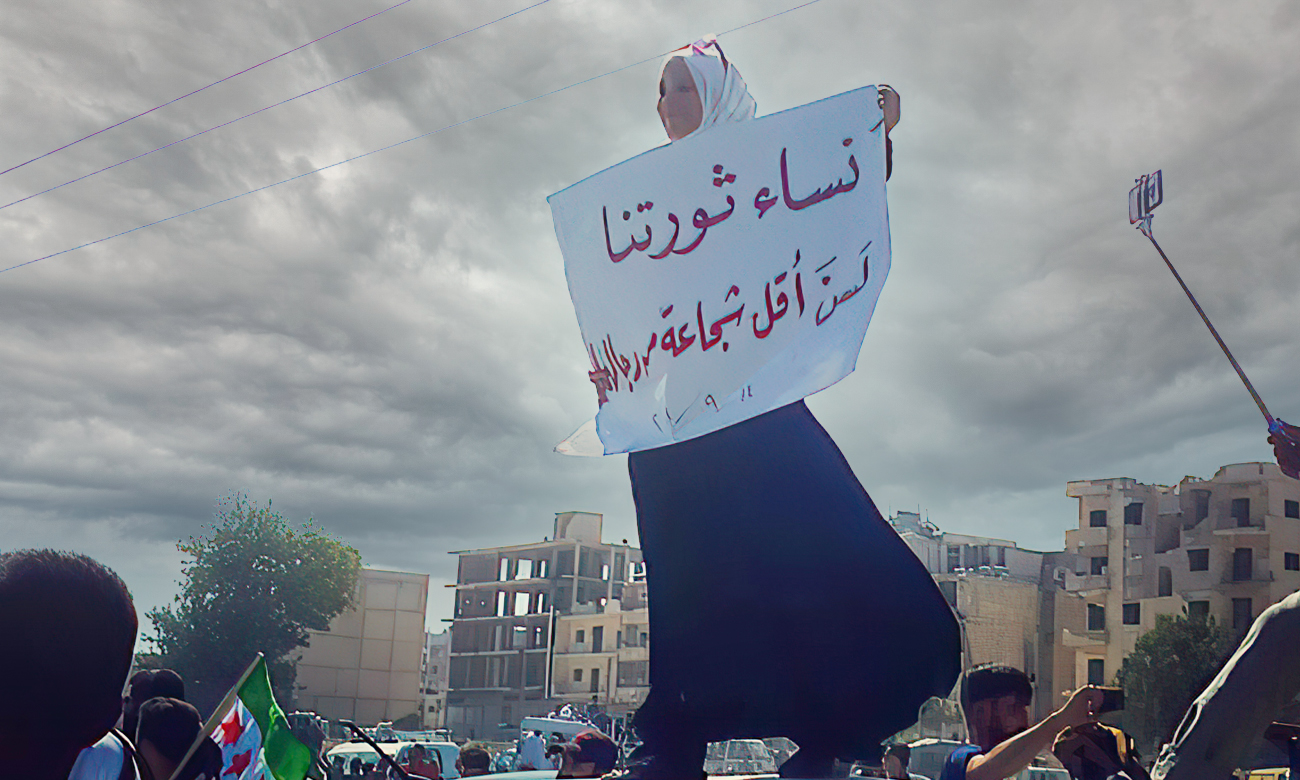

In 2011, the Syrian people placed their hopes on the revolution, which called for ensuring personal freedoms and changing the country’s political system. However, women’s aspirations collided with a forced reality of a divided country controlled by de facto authorities, each with different laws and political and legislative authorities.

Restrictions against women in northwestern Syria

The northwestern Syrian region falls under the control of two forces, the Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS)-affiliated Syrian Salvation Government (SSG) in Idlib and the Syrian National Army (SNA)-affiliated Syrian Interim Government (SIG) in Aleppo countryside. Each of these two unacknowledged powers has a governing method of its own.

A female volunteer in the Syria Civil Defence (SCD) injecting a child with anti-leishmaniasis drugs – 2021 (Syria Civil Defence)

HTS guarding “virtue” in Idlib

Enab Baladi met several women based in the HTS-controlled Idlib governorate, who complained of the HTS’ male and female hisbah forces’ extreme restrictive measures imposed against women in public places.

Women living in HTS areas are tied down by provisions laid by authorities in the name of sharia law. Such provisions forbid the mingling between sexes unaccompanied by a mahram, starting at the school level and extending to workplaces and everyday spaces like markets.

Women wearing heavy makeup or dressed in eye-catching clothes are also prosecuted by the hisbah forces.

Last September, local social media pages circulated images of banners hung by the Ministry of Awqaf (Islamic Endowments) of the Salvation Government_ the political body of HTS in Idlib_ as part of the “Guardians of Virtue” campaign. The banners read Quranic verses and phrases urging women not to wear makeup and adhere to Islamic dress.

The banners sparked outrage on social media platforms, given the unjustified restriction on women’s dress in Idlib. In addition, the SSG was criticized for wasting public funds on hanging banners calling for modesty, while the area is witnessing a deterioration in the health sector as a result of the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19).

Women in Aleppo countryside face the burden of social norms and beliefs

As for women residing in Turkey-controlled regions in Aleppo countryside, especially those working in civil society organizations, they are being harassed on an individual level by armed members from the Turkey-backed SNA factions.

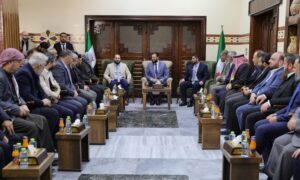

In mid-August, a sermon delivered by the head of the opposition’s Syrian Islamic Council (SIC), Osama al-Rifai, during a visit to a mosque in Azaz city of Aleppo countryside, caused widespread controversy after al-Rifai attacked women working in civil society organizations in northern Syria.

In the sermon, al-Rifai said, “There are women of our skin, who speak our language and are born in our country and cities, who come as recruits from the United Nations and international organizations to spread ideas of what they call women’s emancipation and gender issues.”

Al-Rifai added that some organizations operating in northern Syria work under the cover and slogans of humanitarian relief and development projects to “spread ideas of moral decay and homosexuality, and all that is contrary to the Islamic moral laws and the values of the Syrian religious society.”

After the sermon, Syrians turned to social media to express their opinions, which were divided between supporting and defending Sheikh al-Rifai’s sermon and condemning what he said in terms of “inciting patriarchy and violence against women and the deprivation of their human rights.”

Women living in Aleppo countryside are forced to put more effort when they want to make personal decisions, the director of the Women Support Unit in Azaz, Nevin Hotri, told Enab Baladi.

These women have to convince their surrounding society of the reasons behind a certain decision and its importance on the personal and community level. If their efforts prove successful, they can pursue their decisions, Hotri said.

Conflicting views on women’s reality in northwest Syria

The society of northwestern Syria is viewed as “conservative.” Syrians have different opinions on the primary reasons for harassment, restriction of personal freedom, and denial of human rights practiced against women in northern Syria, in a way similar to their disagreement on most issues of Syrian society.

These opinions are very contrasted and sometimes extreme, as some might deny any restrictions on women’s rights.

Enab Baladi contacted Taqi al-Din Omar, director of media communication at HTS, and asked him about the established rules for dealing with women in Idlib, but Omar did not answer.

In a previous talk with Enab Baladi on HTS’ general orientation of work with regard to the lifestyles of women in Idlib and its controls, rules, and laws on women’s dress, work, and presence in public spaces, and accusations against HTS of harassing women, Omar said, “The Syrian people are Muslims proud of their identity and culture and their commitments to the Islamic teachings in public appearance and occasions, including the dress of men and women alike.”

He pointed out that “violations” sometimes occur in public places, “which are often handled promptly with appropriate direction and guidance. People, in return, receive that with open arms.”

The Minister of Justice of the SIG, Abdullah Abdul Salam, stated to Enab Baladi that legal controls in the SIG areas in rural Aleppo are based primarily on Syrian law.

In response to a question on the SIG’s ability to guarantee women’s rights in Aleppo countryside, Abdul Salam replied that the societal controls imposed by the Syrian society are the basis for handling women’s issues after the law. Abdul Salam attributed women’s lack of participation in various work fields to women’s refusal to do so for fear of security tensions and chaos prevailing in Aleppo countryside areas.

The minister noted that women in Aleppo countryside have a “very active role” in the education and health sectors, confirming that working women do face community pressures, which the ministry cannot control because of living in an “eastern society.”

Women’s rights between authority, inherited societal standards, and Islamic jurisprudence

The de facto authorities governing northwest Syria have imposed a doctrine of control vis-a-vis women, claiming they have the power to establish such rules in line with their vision. This prompted many residents in this region to adopt the same approach or even strengthen inherited social habits.

Dr. Mohammad Habash, founder and consultant of the Islamic Studies Center and founder of the Enlightenment Writers Association, told Enab Baladi that what is happening in northwestern Syria is the “direct antithesis” of what the Ba’ath Party has practiced over the past decades in Syria.

Habash pointed out that by becoming a direct antithesis, the de facto authorities are clearly retaliating to the practices of the Ba’ath Party, which forced people to renounce the Islamic dress.

Habash criticized the de facto authorities’ orientation, saying that “We do not have to be on the far right or the far left. Islam is the religion of moderation and ease versus hardship.”

Habash also slammed the de facto authorities’ insistence on faulty practices of restrictions and discrimination against women and deprivation of simplest rights guaranteed by Islam.

They forced women to dress in the “Hanbali” school code, which does not allow any display from women’s bodies, even their faces, hands, and feet, he said.

Habash explained that the Quranic verse delivered to Prophet Mohammad, “So remind them, you are the only one who reminds. You are not a dictator over them,” sums up the prohibition of bigotry and fanaticism.

Dr. Habash, who teaches Islamic Jurisprudence at the University of Abu Dhabi, additionally added that Islamic jurists had issued many convergent and insightful fatawa (plural of fatwa: a formal ruling or interpretation on a point of Islamic law given by a qualified legal scholar) on the issue of women’s veil (hijab).

In his book “Women Between Sharia Law and Life,” Dr. Habash collected dozens of fatawa by Prophet Mohammad’s companions and other Islamic scholars, all of which revolved around women’s right and responsibility to choose their own dress and to prevent men from interfering in this matter.

The misconception of sharia and its reflection on women

Dr. Habash said that the misunderstanding of sharia is one of the main causes of authoritarian masculinity enhanced by the patriarchal society that “does not believe” in giving women any chance to express themselves creatively.

He added that the misconception of the Islamic sharia provisions is not the only problem, as many abusive practices against women can be traced back to tribal and traditional customs that marginalize women’s roles in life.

|

Four prominent Islamic scholars, Ibn Hajar, al-Qurtubi, Ibn Hazm, and Fakhr al-Din al-Razi, have clearly stated that Maryam, the daughter of Imran (Virgin Mary the mother of Jesus Christ), was a female prophet. There is no doubt that believing in women’s prophecy means they are entitled to hold any position in society. For Islam, prophecy is the highest form of acknowledgment granted to humankind; therefore, women should not be denied their fundamental rights in the name of Islam. Imam Abu Hanifa, a prominent Muslim scholar, jurist, and theologian, said women have the right to hold all positions other than the judiciary, while Imam Ibn Jarir al-Tabari went on to say that women have the right to assume all positions of the State whatever their background, if they possess ability and competence. At the time of Prophet Mohammad, women were active and useful members of their communities. Some of them led free and large-scale trade activities, as Khadija bint Khuwaylid, the first wife of Prophet Mohammad, who ran her merchant family’s business and caravans with half of the Quraysh tribe’s fortune. “I believe that God bestowed Maryam (Mary peace be upon her) with the greatest honor, as there are two Quranic verses in her name (Al Imran and Maryam). Moreover, there is an entire study of doctrines related to Maryam called the Mariology, which broke the chain of male domination in theology.” Dr. Mohammad Habash, founder and consultant of the Islamic Studies Center and founder of the Enlightenment Writers Association. |

A patriarchal society does not tolerate role reversals

Syrian researcher and professor of pedagogy, Dr. Raymond al-Maalouli, told Enab Baladi that most men in northern Syria joined the military actions that followed the outbreak of the Syrian uprising in 2011. Meanwhile, women faced a tough reality, in which they were forced to enter various working fields to fill the roles of men in their families.

This reality enabled women to have active roles in society, where they managed to work, build their self-esteem, and secure their and their families’ needs, al-Maalouli added.

According to al-Maalouli, Women’s success in fulfilling two roles at once, being a housewife and a breadwinner, has caused some men in northern Syria to hold grudges and show strictness against women. They viewed women as competition in all fields.

The dictatorial authoritarianism in line with toxic masculinity in northern Syria has reinforced some men’s strictness and discrimination towards women and incited violence against them, al-Maalouli said.

He added, the authorities in the north rely in their decisions on strict fatawa that have nothing to do with the essence of Islam but are in line with society’s toxic masculinity. They produce restrictions out of wrong jurisprudences, old social customs, and masculine culture standards that help men feel righteous and in control over the women in their lives.

Are men entitled to practice guardianship over women?

Dr. Habash pointed out that male guardianship is at odds with the values of the Holy Qur’an, which based life on shared and equal responsibility between women and men, as stated in the Quranic verse, “The believers, men, and women, are supporters of one another.”

Habash explained that the Quranic verse “Men are the protectors and maintainers of women” tackles the relation between men and women regarding household responsibilities, adding that the concept of wardship is different from guardianship.

According to Habash, wardship is the taking care of women, “with the bounties which God has bestowed more abundantly on the former than on the latter.”

He continued by saying, when women pay for everyday expenses and share responsibilities, the principle of male wardship becomes no longer applicable.

Women have the right to be in charge of their lives and their families’ lives as well, Dr. Habash said.

Community rigid values curtail the impact of women empowerment activities

Through their centers in northwestern Syria, a group of women’s organizations work on activities to empower women socially, economically, and politically. However, these organizations face challenges that slow down their activities’ impact or annihilate it in some sectors.

The director of the Women Support Unit of the Stabilization Support Unit (SSU) in Aleppo countryside, Nevin Hotri, said that the unit is working on providing training that would enable women to play an active role in society and better understand and comprehend the conflict in the region.

The Women Support Unit launched its first founding conference in Azaz city in 2018 with the participation of 150 women. The conference was followed by a huge outcry on the concept of women empowerment, which coincided with a campaign entitled “Enough Violence.” The conference was linked to the campaign, which included mural paintings of a hand with the words “Enough Violence.” The murals were seen as a provocation by some people of the region, who covered the paintings with the phrase “Our women are not subjected to violence.”

Later on, the Women Support Unit adopted a more community-friendly and sensitive approach in addressing women’s issues. A year after the unit’s first founding conference, nearly 1,500 women from six areas of Aleppo countryside participated in a second conference, which was not attacked in the same way the first conference was attacked.

According to Hotri, this change illustrates a shift in society’s thinking. Today, there are individual responses or attacks directed towards a specific entity without causing public outrage.

Gender stereotypes and women’s career choices

The absence of community awareness of the importance of women’s presence in decision-making posts away from the stereotyping of women as working only in the educational or medical sector poses a challenge to the work of organizations that support and empower women. It forces them to take shy steps so as not to provoke society.

According to Hotri, there is no direct targeting for any of the women’s centers of the Support Unit, not since the “Enough Violence” campaign that coincided with the unit’s first founding conference in 2018. Still, harassing another organization or closing it down is harassment against all organizations devoted to supporting and empowering women.

Hotri also said that many women expressed their wish to work in the political field in previous political workshops held by the Support Unit. They seek to empower themselves politically, but they fear public appearances because any female political participation would be received with harsh reactions from society.

Cyberbullying and women oppression

Elham Ashour, the director of Souryana al-Amal Team organization in Azaz, said that women in northern Syria face more harassment on social media platforms than in real life.

Ashour added that the organization is not facing any restrictions or harassment and continues to hold workshops and training on community reintegration, digital security, and women’s rights. Still, the organization is cautious about naming these training projects; for example, a gender-based training program would be announced to the public under the name of “social roles” to be more accepted by people.

According to Ashour, the organization has a certain publishing policy that protects it from having any problems with local authorities, which have a good relationship with the organization.

There is no logic in having local councils exercising power over civil society organizations, Ashour said.

|

“Cyberbullying against women workers in public affairs makes many women reluctant to show their personal images on social media, not because of social or religious reasons, but because of smear campaigns that could be launched against them, amid failed attempts from organizations to protect them. Syrian activist Nevin Hotri |

Are women’s organizations effective in northern Syria?

Enab Baladi conducted an opinion poll on its official website and social media platforms on the role of women’s organizations in northern Syria. The poll was answered by 1566 persons, of which 67 percent said that the organizations have a limited role in supporting and empowering women and changing society’s attitudes towards them, while the remaining 32 percent said the opposite.

The author of studies and member of the board of Women’s Empowerment (Mazaya) Office in Idlib, Ethar Allam, said that vocational training has a good positive impact, but the challenge lies in finding jobs for female trainees after training, given that society lacks large-scale production projects that could provide good job opportunities for women.

According to Allam, most productive enterprises are small and at a modest individual level. As for academic training, the office focuses on improving women’s capabilities in available work areas, but the lack of vacancies, demanding job requirements, and the unbalanced distribution of job opportunities are holding women back in the labor sector.

Umayah al-Mousa, a fifty-year-old displaced woman from Kafr Nabl city, said that organizations have a significant role in supporting women morally, empowering them, shaping their personalities, and promoting their intellectual level through academic training and legal and political lectures, so that they can be effective in their surroundings and society, and enable women to make their voices heard and be active in decision-making posts.

Several factors are hampering the work of women’s organizations, including the lack of social acceptance of their work, the de facto authorities’ rigid rule, continuance displacement, instability caused by repeated attacks by the Syrian regime and its Russian ally, and the deteriorating economic situation.

Woman empowerment levels

The Women’s Empowerment Unit in Aleppo countryside, which brings together female participants under a membership system to support each other, offers empowerment programs that fall into four levels:

Training: It covers women with no experience and includes courses in several vocational skills, besides other political or administrative training, to provide female trainees with standard knowledge.

Empowerment: It includes women with previous skills who cannot find places to employ their experiences. The unit announces volunteering opportunities so that women can practice their skills and gain further experience, which would enable them to apply to jobs requiring prior experience.

Participation: This level encourages women to reach decision-making positions in senior departments. It goes beyond empowering women in society to ensure that women can take up top official positions in local councils and administrative posts in civil society organizations.

Networking: It aims to make the unit a part of a larger network through cooperating and coordinating with other organizations to achieve an integrated program of work and cover aspects left untouched by other parties. For example, the unit does not provide jobs but knows that political empowerment of women cannot be achieved without them being economically empowered; therefore, the unit collaborates with other organizations to nominate participants who need employment opportunities.

Economic empowerment is more urgent than ever before

Women were among the most vulnerable groups in Syrian society in the pre-war period. However, after the war, women became more vulnerable and fragile because the majority lost the men in their lives for reasons of death, arrest, or war-related injuries, the social researcher Talal Mustafa told Enab Baladi.

Mustafa added, Syrian women found themselves in an unfamiliar situation, where they had to fend for their children or families alone. These circumstances required Syrian women (wives, daughters, mothers) to take up new roles and enter the working field, just like Western women who lived during the first and second world wars.

In the case of Syrian women, they had to enter the labor market unprepared or unqualified to perform new works, especially those requiring technical or educational skills, as the majority of them enjoyed a knowledge limited to household tasks, Mustafa said.

What made things worse is that the northwestern region fell under the control of radical powers that do not believe in the rule of law or women’s rights, including the right to work. These hardline powers fought women’s employment and sought to repress them.

The governing powers in this region issued many laws attacking women’s rights in working and ensuring that they stay trapped in household duties, denying women dignified social roles, with the help of community outmoded customs and traditions.

According to Mustafa, the role of associations and supporting organizations is to train and empower women with training programs to equip them with real professional skills, not only to provide food aids (food baskets).

Women are truly supported when they are economically empowered, Mustafa said.

This way, women can develop professional skills and enter the employment market to claim their legal and social rights.

Mustafa added, a change in society can also be achieved, even if a slow one, where people can stop looking at women as inferior beings to become active members of society.

Financial independence is power

Years of working with women in northern Syria have made activist Bayan Rihan, who previously held the position of the head of the Women’s Office of Douma city’s local council, believe that women’s economic empowerment is a priority to be followed by social and political empowerment.

Rihan said that the importance of economic empowerment comes from the fact that most women’s problems and exploitation are attributed to financial needs. By helping women to be financially independent through presenting economic projects, we can ensure a direct solution to this issue.

According to Rihan, the recent years’ economic support for projects in the northwestern region did not help women or men due to the lack of support sources.

Still, many previous projects involved women in their management or implementation plans and helped many of them to become financially independent, Rihan said.

Gender-based discrimination

The social researcher in the Gender-Based Violence (GBV) Guidelines, Ahlam Turki, said that women face gender stereotyping in the Arab region, northwestern Syria included.

Society thinks that women are inferior to men and give men the upper hand, while in fact, women need more liberty to fulfill their potential, she said.

Turki referred to the freedom of thought, mind, and education in her talk, not to the freedom of nudity or obscenity.

To reach their goals, women need to prove their competency to society, which might take years and tremendous effort to prove that women can be a primary or supportive element in developing or modernizing societies.

Women in northwestern Syria are subject to gender-based discrimination. They are denied access to resources or opportunities, while men are encouraged to take up higher and more important roles, according to Turki.

Syria among world’s most dangerous countries for women

Syria ranked the second country from the bottom of the Women, Peace and Security Index (WPS), according to a report released in October 2021.

According to the WPS, Syria is the worst worldwide in organized violence and the worst regionally for community safety. The WPS’ statistics were based on women’s conditions within three dimensions:

- Inclusion (education, financial integration, employment, mobile phone use, parliamentary representation)

- Justice (lack of legal discrimination, bias, discriminatory norms)

- Security (partner violence, community safety, organized violence)

Source: Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace, and Security (GIWPS) and the Prio Center for Gender, Peace, and Security in the United Nations

if you think the article contain wrong information or you have additional details Send Correction

النسخة العربية من المقال

-

Follow us :

A

A

A

A

A

A

More Investigations

More Investigations