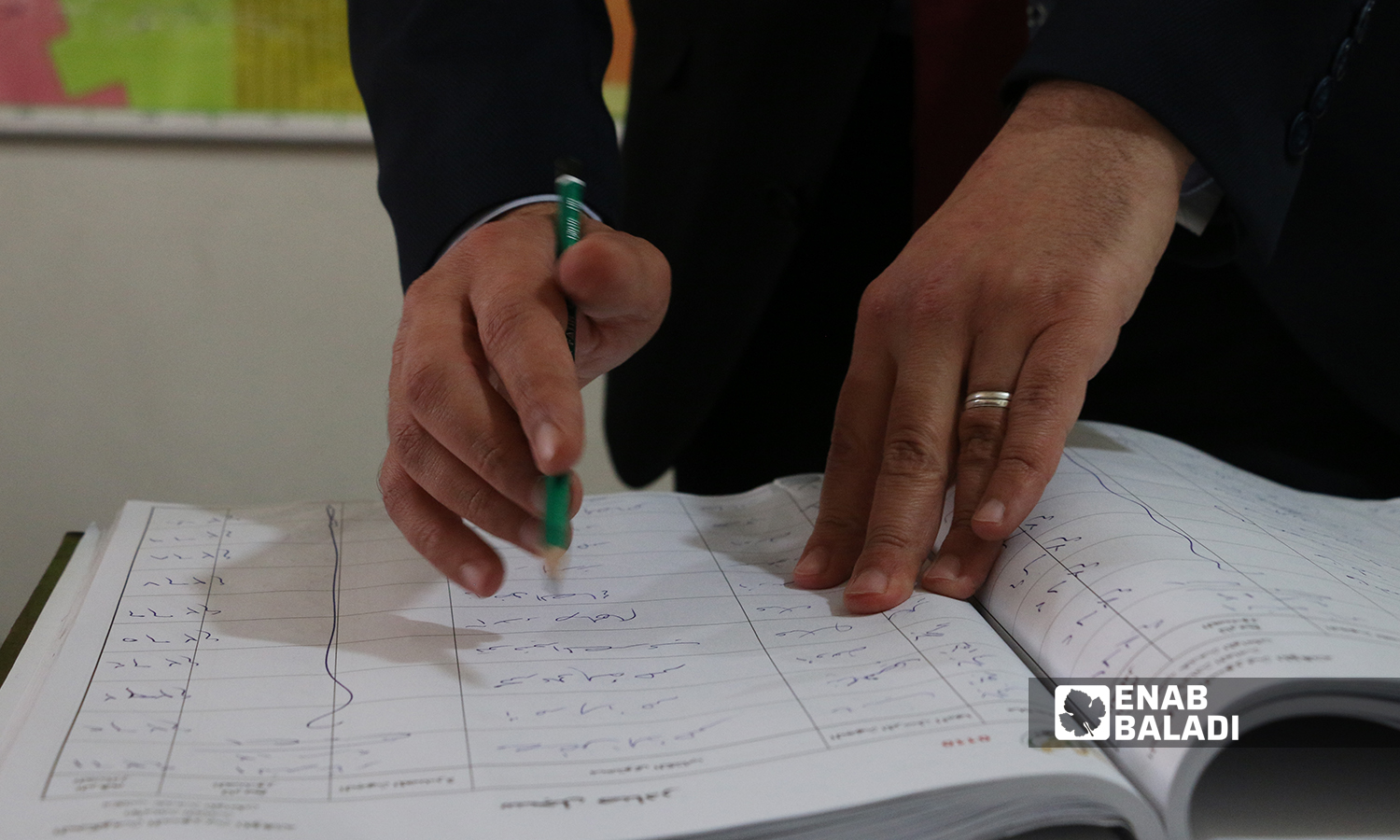

The authentication of diplomas at the Citizen Service Center (CSC) in Gaziantep (Enab Baladi)

Investigation team: Lama Rajeh| Ibrahim Hussain| Ali Eid

The investigation was supervised and edited by Ali Eid / Syria Indicator

Alaa, 28, was a student at the University of Aleppo before he was forced to seek refuge in Turkey. He tried to authenticate his high school diploma at the Citizen Service Center (CSC)— operated by the Syrian Interim Government (SIG)— hoping to resume his disrupted education in Turkey. Therefore, he sent the center his official documents twice by mail. Every time, he would gather the documents in an envelope, along with 55 Turkish Liras (TL) fee. Each time, Alaa was returned the envelope with the money missing and the documents unauthenticated.

Nearly a year ago, Alaa, who ended up running a small shop in the city of Gaziantep, south of Turkey, went to the CSC. The center’s door was shot, baring out a group of young men and women, including himself.

Denied entry, the group was met by a CSC female employee. She dismissed them, saying, “we are not receiving any clients due to COVID-19.” Worse yet, she did not instruct them on any alternatives that would help them overcome the authentication barrier.

Then, the CSC director showed up. He repeated the employee’s words, refusing to answer any of the group’s questions or even consult them on how to proceed with the authentication measures.

Alaa told the investigation team that he appeared on a TV program to shed light on his dilemma. To his shock, Alaa received two threatening phone calls. The first time, the caller told him, “how dare you criticize the government of the Syrian Opposition Coalition (SOC) or discuss matters that are beyond you!”

The second caller, also threatening, told him, “should you ever again bring that issue up, you will be in big trouble!”

Alaa said that the two callers were unknown, for neither of the numbers appeared on his phone screen. However, the investigation team could not verify these claims.

Alaa is not alone in this. Numerous Syrian students fled areas across the country, weighed down by the burdens of war that deprived them of access to university. They all share the same dream. They wish to pursue their education like those people who have a normal life, but all they have got was additional suffering, perpetrated by institutions supposedly established to assist them achieve their dreams.

Since 2011, millions of Syrians have been forced to abandon their homes to escape death. Some were displaced to camps and other areas within Syria; some sought refuge in far away or neighboring countries, such as Turkey. According to the Turkish Directorate General of Migration Management’s figures, by late March 2021, the number of Syrians in Turkey amounted to approximately 3.7 million, who are registered as holders of the Kimlik— the temporary protection document— and 57.502 of whom are housed in camps.

On the condition of his anonymity, one Syrian employee at the Turkish higher education sector said that several negative indicators demonstrate that a catastrophe is looming over Syrian specialized staffs and university diploma holders.

This, he stressed, threatens the future of resuming disrupted development and reconstruction in Syria should refugees return home.

Indeed, figures issued by official bodies confirm that the number of Syrian university students in Turkey was a little above 27 thousand for the 2019-2020 school year. In other words, only seven in every 1000 Syrian refugees are receiving university education.

This rate is staggering compared to rates among Turkish citizens. On 12 February 2021, the state-run Anadolu Agency quoted the Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan as saying that one in every eight Turkish citizens is pursuing university education. Putting the two rates in context, there appears to be 18 times more Turkish university students compared to Syrians.

The authentication of education documents in Turkey remains an urgent issue for Syrian refugees, particularly high school diplomas issued by Syrian education directorates. Students cannot access universities without adhering to that measure. Consequently, thousands of such diplomas were sent to the CSC, where students received a shocking treatment, witnesses told the investigation team. A large segment of the diplomas were returned to students unauthenticated, even though the documents were official and despite the repeated attempts that students made.

Many students lost the chance of joining classes, including A. R., 35, who asked that his name be withheld for security reasons.

R. told the investigation team that he did not mail the diploma, preferring to deliver it to the CSC in person. There, the employee told him that his diploma was fake. Consequently, he was forced to pay money to obtain five copies of the high school diploma from Deir Ezzor city, which he escaped becoming a refugee in Gaziantep city.

R. added that his efforts were to no avail because the employee refused to authenticate the document once again, asking him to obtain the cardboard copy of the diploma, knowing that the employee did not inform him that authentication required that he submit the cardboard copy. Ultimately, R. grew desperate of the process. After a year and a half he spent waiting to get the authentication done R. gave up on the dream of pursuing a university education.

Fake documents sounded the alarmOn the condition of anonymity, a Turkish official who worked in the authentication of diplomas confirmed that before 2016 numerous students submitted fake documents, which were discovered as forged when the seals were thoroughly assessed. The situation necessitated coordination between education directorates and the Directorate General of Migration Management. He added that the issue started to spiral out of control, forcing concerned directorates to cancel the registration of some students. Later, the SIG— an affiliate of the National Coalition of Syrian Revolution and Opposition Forces, also known as the Syrian Opposition Coalition (SOC)— signed a deal with the Turkish Education Directorate in Gaziantep. The agreement provided that submitted documents would be rejected unless they carried the SIG’s seals. The decision was generalized to all Turkish education departments. The SIG founded the CSC in late August 2016, nearly three years into the SOC’s decision to establish the SIG, a step embraced by Turkey. The Gaziantep-based CSC was established to provide services to Syrians across Turkey and help them process matters related to official documents more swiftly, particularly students. |

Lawyer Youssef al-Nairabani was the first to hold the position of the CSC director in 2016. Back then, he said, the center chiefly authenticated high school diplomas issued by the SIG and the government of the Syrian regime. The SIG had the data of its issued diplomas stored on CDs. The data were obtained from the education directorates in the liberated areas—the areas that went outside the Syrian regime’s control before 2015. He added that the services were free of charge and offered in a disorganized manner.

Following the SIG’s staff changes in July 2016, the CSC started operating under the General Secretariat of the SIG.

Al-Nairbani told the investigation team that he stayed in office for four months only, unable to continue working for the CSC following a dispute with the president of the SIG, who personally intervened in the CSC’s work and hampered the service flow.

Al-Nairbani resigned in early 2017, before which he proposed a structure for the CSC and a service list, including authentication of diplomas. His proposal was ratified by a decision from the Council of Ministers.

One of the firsts that an Istanbul-based student experienced while authenticating his diploma is that the CSC added the SIG’s seal to the diploma and later erased it using correction fluid.

The witness, whose name is withheld for security reasons, said that he resorted to a brokering office to manage the authentication process for him. The office mailed his and other four diplomas to the CSC. However, the envelopes containing the diplomas with three of the documents were returned. The diplomas bore the marks of correction fluid, apparently the seal was added and later erased. A notice was attached to the documents, saying “the diploma must be sent by the concerned person himself,” not by a broker.

Astounded, the witness recounted his story. He had to pay about 700 USD to obtain an original copy of his diploma from Syria. He is a graduate of an intermediate institute, coming from a town near Damascus.

The witness is still afraid to call or even refer to the CSC after he appeared on a TV program exposing the way the CSC employees handled his diploma, even though one media outlet played the intermediary and resolved the dispute between them.

“I wanted to enroll with some university, complete my education, and attempt to create myself a future,” the witness, who recently works at a Shawarma restaurant, said desperately.

He added that he resorted to a broker to submit the diploma because he could not travel to Gaziantep, being his family’s sole breadwinner and thus unable to leave his job.

He blames the CSC employee, who “does not have the slightest sense of responsibility” and is ignorant of the document’s value, which should not be subjected to any alterations or erasures.

A diploma damaged by a CSC employee, who applied a correction fluid to the document after adding the SIG seal, lower left corner. The name of the diploma owner was removed at his request.

One of the witnesses interviewed by the investigation team is an SIG employee. Asking that he remains anonymous, the employee claimed that a “theft operation” was revealed in which perpetrators stole some part of the money citizens paid as an authentication fee for all kinds of diplomas, issued by elementary up to high schools, whether those that offered sharia, agricultural, trade, literary or scientific schooling.

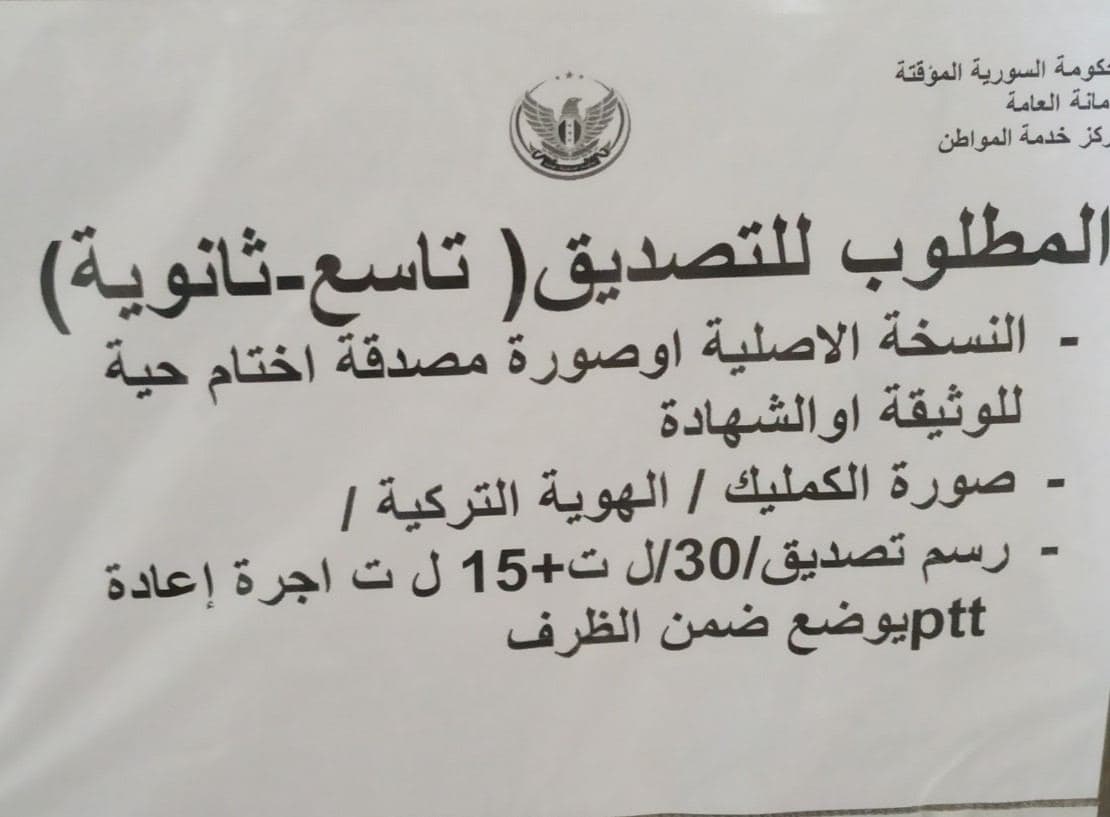

The employee said that the SIG started a probe which exposed that the former CSC director and two employees have divided among them the extra money left of the postage costs. He explained that citizens applying for authentication pay a fee of 30 TL and send additional 15 TL for the CSC to mail them the diplomas back, adding that postage fees are less than 15 TL.

The employee confirmed that the SIG initially dismissed the involved employees. However, the SOC and the SIG Secretary-General Fayez al-Nabi refused the dismissal, for it would have adversely affected both the SOC and the SIG. Accordingly, the SIG only relocated the CSC former director, sending him to another directorate, intending also to gradually transfer the other involved employees, without dismissing them or even laying any punitive measures against them.

Moreover, the witness said that there was a lot of brokering business going on at the CSC and rampant chaos, which resulted in the loss of numerous diplomas. In response, the CSC issued lists of the names of persons who lost diplomas, alleging that they have provided the CSC with wrong addresses and demanding that they refer to the CSC or call the center to get their diplomas back.

The investigation team reported the employee’s testimony and the suffering of persons affected by poor authentication services to concerned bodies.

The SIG’s Secretary-General al-Nabi responded to the claims discussed above, saying that they are made by persons disadvantaged by the “SIG’s diploma authentication services.”

He added that these people have carried out “defamation campaigns on social media that resulted in much ado about the CSC’s work.”

Al-Nabi held responsible the authorities of the Syrian regime and their affiliated consulate in Istanbul, not excluding “brokering offices that took money from students to mail their diplomas without a power of attorney or a legal document [that empower them to carry out such services on behalf of the students].”

He added that “there are also cases of forgery carried out by some ill-intentioned persons,” stressing that these people might also have benefited from the defamation campaign.

Commenting on the investigation that ended with transferring employees, instead of dismissing them, al-Nabi refuted the claims as untrue altogether, adding that these transfers were “internal measures to improve the CSC’s services.”

Upon visiting the CSC, the investigation team coincidently came across an envelope that was opened before it reached the CSC. The money the sender included in the envelope was missing. This indicates that the CSC is either facing organizational troubles or the money has been simply lost, or otherwise embezzled. The investigation team asked the SIG and the CSC employees about these potential scenarios. However, everyone seemed reluctant to directly hold a specific side accountable for the situation.

The SIG Secretary-General al-Nabi attributed the incident to the fact that the CSC does not have a bank account. He added, “we [the SIG] are a political institution with political recognition, we are not an institution with legal personality in Turkey. Accordingly, we cannot open a bank account. But we did not spare effort, and we continue to search for a solution through communicating with Turkish officials.”

We asked Secretary-General al-Nabi whether the CSC could use the SIG’s existing bank account and whether it was opened in the name of individuals because the SIG is a political entity, not an institution with legal personality as indicated earlier, as well as how is the SIG capable of putting the account into use given the implications he referred to. However, al-Nabi’s answer was ambiguous, for he did not disclose the nature of the SIG’s bank account, saying that “it is a different issue.”

Recently, the CSC cut postage fees down to 15 TL instead of the 20 TL it charged clients before, in addition to the 30 TL authentication fees.

A number of the witnesses interviewed by the investigation team said that they paid the remailing fee even though they were returned their authenticated diplomas in person. That is, the remailing fee is being withheld by an unidentified side.

The CSC director, Trad al-Sa’doun, refuted that such money thefts exist and preferred not to provide any information about the period before he came into office in February 2021.

He added that some envelopes arrive at the CSC without the fee and that CSC sometimes pays extra money above the defined remailing fee. At the same time, he did not deny that in some cases envelopes come with extra money, no more than a few TLs.

Al-Sa’doun added that the CSC signed an agreement with the Yurtiçi Kargo Company to organize the diplomas’ remailing process.

The investigation team also reached out to an official from the Turkish PTT— the National Post and Telegraph Directorate of Turkey— discussing with him the issue of extra remailing money that has been going missing. The official said that putting the money in the same envelope with diplomas is illegal, but sometimes the post office employees ignore the laws. This actually corroborates the testimonies of several Syrian interviewees who confirmed that post office employees prevented them from putting the money inside the envelope containing the to-be-authenticated diplomas; others said that the employees did not mind it.

Pertaining to the fees, the PTT official said the SIG often pays 16 to 20 TL to return authenticated documents to owners, depending on the weight of the documents. The PTT has its fee fixed. Remailing documents below 20 g costs 16 TL. Notably, that 20 g is the weight of a file containing 5 A4 papers.

The fee becomes 20 TL for the envelopes weighing between 20 and 100 g.

Khalid al-Hamad, the CSC accountant, explained the way the CSC handles the money sent or personally paid by clients. He said that fees are collected and “documented in invoice books in three copies, one copy of the invoice remains attached to the book; one is added to the client’s file; and a third is given to the client.”

Al-Hamad stressed that the money received is registered in a daily register, mentioning the name of the payer, the date of payment, as well as the sum paid. Then, the register is matched with the invoices and the number of the authenticated documents. At the end of the day, the revenues are collected. These revenues are sent at the weekend to the central treasury of the SIG’s Ministry of Finance.

Image taken at the CSC of the list indicating the fees of authentication and remailing services (Enab Baladi)

A number of the witnesses interviewed by the investigation team said that the CSC was closed for a lengthier time than the lockdown imposed by the Turkish government in response to the COVID-19 outbreak. The CSC director al-Sa’doun admitted this, saying that the closure corresponded to the time when universities started receiving registration applications; namely, between May and October 2020.

Yahiya al-Abdallah, the CSC former director and current employee, attributed the long closure to the positive COVID-19 cases among the CSC staffs. He added that in August 2020, the CSC employees were quarantined for 14 days during the universities application season.

To ensure that students would not lose the chance of applying to Turkish universities, the CSC communicated with the Turkish Ministry of National Education to extend the registration deadline for students, considering the exceptional situation the CSC was experiencing. The ministry approved the request, al-Abdallah said.

He added, “We assure you that none of the students who intended to apply for universities back then were adversely affected.”

Closures apparently were not limited to the university application season. Al-Abdallah’s account contradicts with Raghda’s testimony. Raghda, 39, lives two streets away from the CSC and when she visited the center in March 2020 to get her diploma authenticated, she came across a group of clients. They were barred outside and left with a bunch of unanswered questions. Consequently, Raghda mailed her diploma with 50 TL. The center took nearly 45 days to authenticate her document despite all her efforts to speed up the process.

According to witnesses, the SIG did not come up with any alternatives to meet the students’ needs, leaving clients to their own devices. Many students lost the chance to enroll with universities; other clients had their work hampered due to delays. This stands at odds with the CSC officials’ accounts.

Several of the witnesses met for the purposes of this investigation complained of the bad treatment they received from the CSC employees, particularly former CSC director Yahiya al-Abdallah, whom they called a quite “influential” employee.

The witnesses’ testimonies corroborate the account provided by the Turkish official from the Gaziantep Education Directorate. The official, too, maintained contact with al-Abdallah.

The official said that al-Abdallah obstructed the authentication of documents submitted by numerous clients for unfathomable reasons, adding that he even refused to sign some documents claiming they were fake while they were authentic. The Turkish Education Directorate confirmed that these documents were authentic through its verification system and mechanisms. The official said many students were robbed of the chance to register with universities, while many clients were denied the authentication of their diplomas or other documents.

Pertaining to the employee’s account who said that chaos was the reason for the loss of a large number of diplomas, the investigation team verified that the CSC issued three lists with 338 names of people who did not receive their diplomas back and who were asked to refer again to the CSC— the first list included 133 names, the second 172, and the third 33.

For his part, al-Abdallah said that CSC addressed the submissions of the clients on all three lists and that they were sent their documents. However, these documents were returned to the CSC because clients provided wrong addresses or phone numbers.

The team discussed several of the issues the investigation addressed with Dr. Zaidoun al-Zoabi, seeking his experience with government and private entities, as well as international organizations as a specialist in governance and quality management.

Pertaining to the fees chaos and the difficulties of opening a bank account, al-Zoabi said that these issues must be treated based on the principles of good governance, particularly transparency, participation, and inclusion.

People must be transparently informed of the complexities and difficulties and must also be heard. This urges people to participate and respect the administrative procedure. How are people supposed to understand the CSC’s inability to open a bank account because it operates as a political personality, not a legal one, while the SIG has an account despite similarly functioning as a political personality?

When people are not shared information, they become skeptical because “people tend to be the enemy of the unknown,” al-Zoabi said, adding that the people’s inability to understand what is happening leads to a generalized doubt, which is an essential dimension of the corruption resulting from an ignorance of the principles of management and good governance, not theft.

Al-Zoabi pointed out that institutional corruption is largely the result of ignorance or mismanagement, and is mostly unintentional, adding that corruption might arise from poor organization, whereby the institution might have good intentions but lack a knowledge of management.

Al-Zoabi also commented on disorganization during the COVID-19 outbreak, the undone work under lockdown, and the tumult the witnesses reported, saying it caused several people to lose opportunities of paramount importance.

He said that these problems relate to a fourth good governance principle, which is effective response. Under this principle, the administration should resort to risk governance. This does not only include predicting risks, but it also entails visualizing a response, deciding who will be in charge of this response, and coming up with censorship and follow-up tools.

About the hundreds of clients who have allegedly provided the CSC with wrong addresses and phone numbers, and thus lost their diplomas, al-Zoabi wondered, “has the CSC set up an email-based parallel measure that guarantees clients would not loose documents or that these documents would not remain undelivered?”

He added that such problems occur when institutions work without alternative plans or studying the risks. When circumstances, like those that accompanied the COVID-19 pandemic, emerge, responses tend to be arbitrary, adding that this is not specific to Syrians, for some developed countries experienced similar challenges, meaning that part of mismanagement might be outside our control.

Responding to questions regarding living up to responsibilities, accountability and transparency, al-Zoabi posed two questions: how can we seek accountability without evidence? How can we obtain evidence without a documented process, or basing the process on the principle of participation? These elements are all connected.

He added that there is corruption in many places that cannot be verified for lack of evidence obtained through documented processes and administrative actions made over clear stages as to predict gaps relating to any of the involved stages and work out solutions and alternatives to prevent flows or corruption. For example, financial reports audited by a third party help overcome potential corruption, but in the absence of such a practice, which is the case with Syrian institutions, the odds are high that unproven corruption would occur. This resembles the case of the traffic police officer who issues tickets to vehicles without receipts. This officer might show up at the department with money in his pocket that cannot simply be called stolen for lack of evidence.

Al-Zoabi concluded his account saying that within the Syrian context, mismanagement and corruption can be related to a variety of factors, including lack of experience and existing chaos, as well as security issues, for the eight governance principles lead to perfection when applied together. However, there is not a single institution in developed countries that can put all seven principles into practice literally, “not to speak of Syria, where there is chaos, a variety of powers in charge, poor management, and lack of specialists.”

The investigation sought to verify allegations related to suspected corruption, chaos, and mismanagement, or the citizens’ exposure to bad treatment, as well as the amount of money paid to the CSC.

The investigation draws on a number of interviews conducted with 13 witnesses who got their diplomas authenticated, or denied authentication. Additionally, the investigation team met with former and current CSC and SIG employees and officials, and members from the Turkish post and education directorates.

Based on the witnesses’ testimonies and the thorough probe into the investigation’s subject matter, the team came across rather risker issues relating to the fate of thousands of students who were deprived of the hope of pursuing education in Turkey.

Four witnesses said that they had their documents authenticated without any problems, while the remaining nine reported they were subjected to shocking treatment from the CSC, received threats, or got their documents damaged or lost due to chaos which cost them their academic future.

Secretary-General al-Nabi, on behalf of the SIG, said that the SIG is not considering abolishing the authentication fees and that it has not yet found a solution to the bank account problem, as to fend off corruption accusations involving the said fees or forcing Syrian clients to illegally send these fees in the same envelopes with the diplomas, thus, breaking the Turkish laws.

Speaking of the CSC’s past achievements while promising that many are to come, al-Nabi answered the investigation team’s question— whether the SIG should adopt good governance?— saying: we have just started.

Syria Indicator carried out this investigation within the frame of solution journalism. The investigation exposes the injustices inflicted on Syrian students who lost the chance to resume their education with Turkish universities due to administrative chaos and malpractice governing the activities of the Citizen Service Center— operated by the Syrian Interim Government (SIG), which was founded by the Syrian opposition’s political wing.

if you think the article contain wrong information or you have additional details Send Correction