Enab Baladi – Ninar Khalifa

“We had to leave Afrin with a pain that will not be erased from our memory. We left everything we had behind, our memories, our dreams, our photographs, our houses, our cars… We just came out with our clothes. We ran through the streets of Afrin with every rocket fired by Turkish F-16s or a cannon or a tank shell, providing first aid to the wounded and donating blood to save civilian lives. We were lost, not knowing where we were going or where we would settle”.

With these words, the administrator of the Yazidi Union of Syria, Suleiman Jaafar, described the situation of the Yazidis during the Turkish attack with the support of Syrian National Army factions on the city of Afrin and its countryside northwest of Aleppo in January 2018, forcing a large number of them to flee and leave everything they have behind.

“After we left Afrin, some of us headed to regions east of the Euphrates, while others headed to Aleppo and the towns of Nubl and al-Zahraa. Most wandered off to the al-Shahba area in the northern countryside of Aleppo”, added Jaafar.

As military factions took control of Afrin, the Yazidi religious shrines, he recounts, were “the first places to be destroyed and have their contents looted.” The Yazidis who chose to stay in Afrin were “in constant terror, their lives being monitored and unable to practice their religious beliefs freely.”

With the support of Syrian National Army (SNA) factions, Turkey announced its control of Afrin and its countryside northwest of Aleppo on 18 March 2018, after the factions penetrated into the city center and advanced at the expense of the (Kurdish) People’s Protection Units (YPG) in an operation dubbed Olive Branch.

According to the United Nations, taking control over the city had led to the displacement of more than 137,000 people.

Among the most prominent factions in control of Afrin are al-Hamza Division, Suleiman Shah Brigade, al-Waqqas Brigade, Sultan Murad Division, Ahrar al-Sharqiya, Jaysh al-Sharqiya, al-Jabha al-Shamiya, and Faylaq al-Sham.

After leaving Afrin, Jaafar headed to al-Shahba, where the (Kurdish) Autonomous Administration urgently established several camps in late March 2018 to house displaced persons fleeing Afrin. Some of those who fled have lived in empty uninhabitable homes, having served for years as an arena for the fighting in the region between the various parties to the Syrian conflict.

“No one was there when we reached al-Shahba. The displaced had to clean up houses that were destroyed and full of bodies, dirt, and all kinds of remnants of war”, he says in this regard. He recalls how the Autonomous Administration hastily established a camp in the Fafin area, dubbed Barkhdan (The Resistance) camp. After this camp became overcrowded, it was forced to set up a second camp in Tall Susin called Sardam (al-Awda) camp. The Autonomous Administration also tended to the necessary needs of the displaced.

Afrin’s displaced people firmly believe they will return to their areas and homes one day. This helps them cope with the difficulties they face as a result of their displacement.

Jaafar explains that “All the displaced people have lost everything they owned, and displaced people from other areas are now living in their homes.” “Personally, I lost two houses, a tourist car, and a villa in my village of Basofan that was equipped with all the amenities and luxuries, along with five properties planted with more than five hundred olive trees and more than two hundred different fruit trees,” he adds.

The Yazidis believe in one God. They were named after their religion, “Ezi/Ezid/Yazdan,” which is an Indo-Iranian vocabulary that means God, “high soul,” or “pure soul worthy of worship.” They speak Kurdish and are mainly found in northern Syria and Iraq.

In August 2014, Yazidis faced massacres and abductions by the Islamic State (IS), which carried out atrocious crimes against them in the Iraqi Sinjar/ Shangal district. IS also led Yazidi women as Sabaya and Jariyat (women captives in war and slave-girls) for its elements, even the youngsters among them, to its areas of control in Syria, which the United Nations classified as a “crime of genocide.”

The Yazidis are located in 22 villages in the Afrin region, some of which have become completely vacant of their original inhabitants, according to what the Kurdish journalist from Afrin, Mohammad Blou, explains. He said that the number of Yazidis in Afrin prior to Operation Olive Branch was estimated at approximately 25,000. Since the Turkish forces entered the city, there are only 5,000 people left in the city of Afrin who have been stuck there after fleeing the surrounding villages.

Later, those fleeing to al-Shahba and east of the Euphrates were able to cross into Iraqi Kurdistan or migrate to Europe.

After the military operations in the area ended, some Yazidis returned to their homes. However, some of them were re-displaced as a result of the violations to which they were subjected. To this day, the region is still witnessing a displacement of Yazidi families due to the conditions they face.

Blou points out that some Yazidi villages are currently empty of their original inhabitants, such as the village of Pavilion in the Sharran district, which contains about 150 houses and is controlled by al-Jabha al-Shamiya. A small part of Yazidis also returned to the village of Faqira in Jindires, which is under the control of the al-Hamza Division and is currently inhabited by displaced people from Homs and Ghouta. Besides, there are mixed villages where Yazidis and Muslims live, such as Basuta and Shadera (Sheikh al-Deir).

Yazidis in Afrin suffered systematic violations by National Army factions. Apart from their displacement, some of them were assaulted and had their property looted and their religious shrines destroyed, as explained by the director of the Ezdina Foundation, Ali Esau. He notes that the same situation was repeated in the city of Ras al-Ain (Sere Kaniye), northwest of al-Hasakah, after the Turkish forces took control of it in cooperation with the Syrian National Army (SNA) in October 2019 during an operation called Peace Spring.

The Ezdina Foundation has documented the direct killings of many Yazidi civilians by individual weapons and hand grenades “with extremist religious motives,” according to Esau; this was carried out by its field team responsible for monitoring violations in Afrin areas in secret owing to the deteriorating security situation. In addition, some Yazidis were forced to convert to Islam.

The foundation also monitored cases of abductions and killings of Yazidi women, which it attributed to “provoking Yazidis to expel the rest of them in Afrin,” including the killing of young Yazidi woman Narges Dadu (24 years) in the village of Kemar in the Afrin countryside in November 2019, and Ms. Fatima Hamki, who was killed inside her home in June 2018, after a member of the al-Hamza Division threw a bomb inside it after she refused to exit it and leave it to newly displaced people.

In her testimony, one of the detainees told the foundation that she was subjected to questions of a religious nature from elements of the National Army and that she was forced to convert to Islam. Esau said that her detention was extended because of her refusal to convert to Islam.

For her part, the joint chairperson of the Union of Yazidis in Afrin, Suad Hasso, speaks of Yazidi women being subjected to violence and being placed under arrest by National Army factions, noting that some of them have been released while others remain imprisoned.

One of the detainees was Ghazala Salmo from the village of Basofan in Sherawa district, who was arrested last December on charges of booby-trapping the car of a leader in al-Jabha al-Shamiya according to Hasso, who indicated that Salmo was subjected to severe torture as a result of which she lost her memory, and she is currently still imprisoned.

Violations continue against Yazidi women in Afrin, such as forcing them to leave their religion and convert to Islam with death threats and imposing black dress upon them.

In addition, Hasso says that abductions of Yazidis in exchange for ransom, taxing their property, settling faction families in their homes, destroying their religious shrines, and building mosques in their villages are prevalent in Afrin.

In a report issued in September 2020, the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on Syria indicated that National Army factions had detained Yazidi women. During their interrogation, they were invited on at least one occasion to convert to Islam.

The Yazidis of Afrin are subjected to religious restrictions as they are prohibited from celebrating their religious occasions and giving Yazidi religious lessons. In its 2020 report on Syria, the US Commission on International Religious Freedom criticized the persecution and marginalization of religious and ethnic minorities, especially Kurds, Yazidis, and displaced Christians in Turkish-held areas, such as Afrin.

The report called for pressure on Ankara to establish a timetable for its withdrawal from Syria, “as its presence there may exacerbate the religious and ethnic cleansing of Yazidis, Christians, and Kurds.”

Suleiman Jaafar recounts that pressure on Yazidis in Afrin was exacerbated after the US Commission made a scathing critique of Turkey in its report.

“What happened later was terrible,” he says, “A group of the people of al-Ghouta held a meeting that not a single Yazidi had attended. Claiming that they are Yazidis, they issued a statement saying that they see no objection to building mosques in Yazidi villages and for Yazidi women to wear Islamic dress….” This is being imposed upon Yazidis to date, in conjunction with depriving them of practicing their religious rites.

Jaafar appealed to the countries concerned, especially the United States and Russia, human rights organizations, the European Union, and the Organization of the Islamic Conference, to pressure Turkey to leave Syrian territory and facilitate the return of forcibly displaced people to their homes.

Houses on the road between the villages of Jalbal, Marimeen, and Anab in Afrin – 11 March 2018 (Enab Baladi)

There are more than 18 Yazidi religious shrines in Afrin, most of which were deliberately destroyed, vandalized, or looted. In addition to that, sacred trees were cut down, and Yazidi cemeteries were desecrated and demolished.

A video released by the Ezdina Foundation in May 2018 showed the destruction of the shrine of Sheikh Junaid in the village of Faqira in the countryside of Afrin after the grave, which is of great importance to Yazidis, was exhumed and looted.

Another video released by the foundation in March 2018 also showed the burning of a “sacred tree” in the village of Kafr Jannah, in the countryside of Afrin, opposite the Hawker Shrine (Qarah Jarnah).

In April 2020, the organization documented the destruction of the Sheikh Ali shrine in Basofan, in the countryside of Afrin, from the outside by bulldozing parts of its dome after it was robbed of its contents and had dirt thrown in it in 2018.

Esau believes that the aim of sabotaging religious shrines is to “attempt to systematically exterminate the Yazidis culturally, target their religious affiliation, and obliterate their historical identity by destroying all monuments that indicate their presence in their historic land in Afrin.”

Esau confirms that this targeting “is motivated by extremist religious reasons that often resemble those committed by IS terrorists in their attack on Yazidis” in Sinjar/Shangal in 2014. “In addition, the demolition of graves belonging to the Yazidis aims to destroy tombs’ headstones and the inscriptions of Yazidi religious forms and symbols engraved on them in Kurdish.”

In a report entitled “Blind Revenge: Cemeteries and Religious Shrines Vandalized by Parties to Syrian Conflict,” Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ) has documented that many historical and religious cemeteries and shrines have been subjected to widespread violations by various parties to the conflict, for reasons that may seem either reprisal or founded on religious or ideological backgrounds, according to the organization.

Violations included burning, vandalism, or theft of graves’ contents. Some of those graves have also been completely obliterated by being brought to the ground and converted into military bases or livestock markets.

In Afrin, the organization’s field researcher counts the destruction of at least eight cemeteries containing civilian and military remains, as well as the exhumation of two Yazidi shrines and the theft of other contents between February 2018 and mid-2020.

The organization referred to the vandalism of the cemetery of the village of Sheikh Khurez in Bulbul district by members of the National Army twice, the first being in February 2018, while the second was in July 2020. The organization also pointed out that the destruction extensively affected graves that had headstones with inscriptions in Kurdish.

In a report, the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on Syria confirmed the deliberate demolition of several Yazidi shrines and tombs throughout Afrin in Qastal Jindo, Qibar, Jindires, and Sharran, noting that this has increased the difficulties faced by Yazidis as a religious minority in areas controlled by the Syrian National Army, and has affected both tangible and intangible aspects of their cultural heritage, including the practice of their religious rituals.

In its report, the Commission added that it had reasonable grounds to believe that combatants of the National Army, in particular members of the 14th Division, the Suleiman Shah Brigade, the al-Hamza Division, and the Sultan Murad Division, had repeatedly committed the war crime of looting in Afrin and Ras al-Ain, and may also be responsible for the war crime of destroying or seizing opponent property.

The demolition of the Sheikh Ali shrine in Basofan in the countryside of Afrin, the Violations Documentation Center in northern Syria.

The Afrin Local Council denies any violations of Yazidis’ rights in the region or any obstacles to the practice of their religious rites.

“There are no systematic violations against any component of Afrin, be they Arabs, Kurds, Christians, or Yazidis. What affects one of them as a result of the ongoing war includes the rest of the components”, says the director of the media office in the Afrin Council, Ahmed Hamaher.

He adds that the reality of Yazidis’ living and work is, in fact, tangible and can be observed by anyone visiting the region.

At the same time, however, he refers to the existence of “individual abuses” by certain military factions, which, according to him, affect everyone without targeting a particular component. He asserts that abuses that may occur by “certain abusive elements” are instantly resolved and that the matter is handled by competent civil, military, and judicial police authorities.

The local official denies the displacement of any component from the area, adding that everyone is practicing their religious rites freely and without being subjected to harassment.

Regarding the housing of displaced families from al-Ghouta, Homs, and Idlib in Yazidis’ homes, Hamaher asserts that if homeowners who are not currently in Afrin were to return, any of them could retrieve their home after submitting a contract proving ownership.

Two members of the Free Syrian Army roaming the villages of Jalbal, Marimeen, and Anab in Afrin – 11 March 2018 (Enab Baladi)

Over the past decades, successive Syrian governments have not recognized the Yazidi religion as one having its own specificity and religious rites, according to the Syrian Judge, Riyad Ali. The government was treating them as Muslims with no regard for their religious idiosyncrasies, in clear violation of the human right to religion and belief contained in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948 and in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights of 1966.

In contrast, the Personal Status Law confers this specificity on members of other religions and sects present in Syria, such as Druze, Christianity, and Judaism. In its articles 307 and 308, the Personal Status Law deals with religious and legislative provisions relating to personal status issues such as marriage, divorce, alimony, custody, inheritance, and others.

Several special laws have been enacted to regulate the personal status of members of many sects and religions in Syria, including Law No. 2 of 2017 regulating inheritance and will for members of the Evangelical community in Syria and Legislative Decree No. 7 of 2011 regulating the inheritance and will of Greek Orthodox and Syriac Orthodox. However, no legislation was issued for members of the Yazidi religion, who were obligated to review Sharia courts, as Muslims in Syria would do, even though they do not adhere to the Islamic faith.

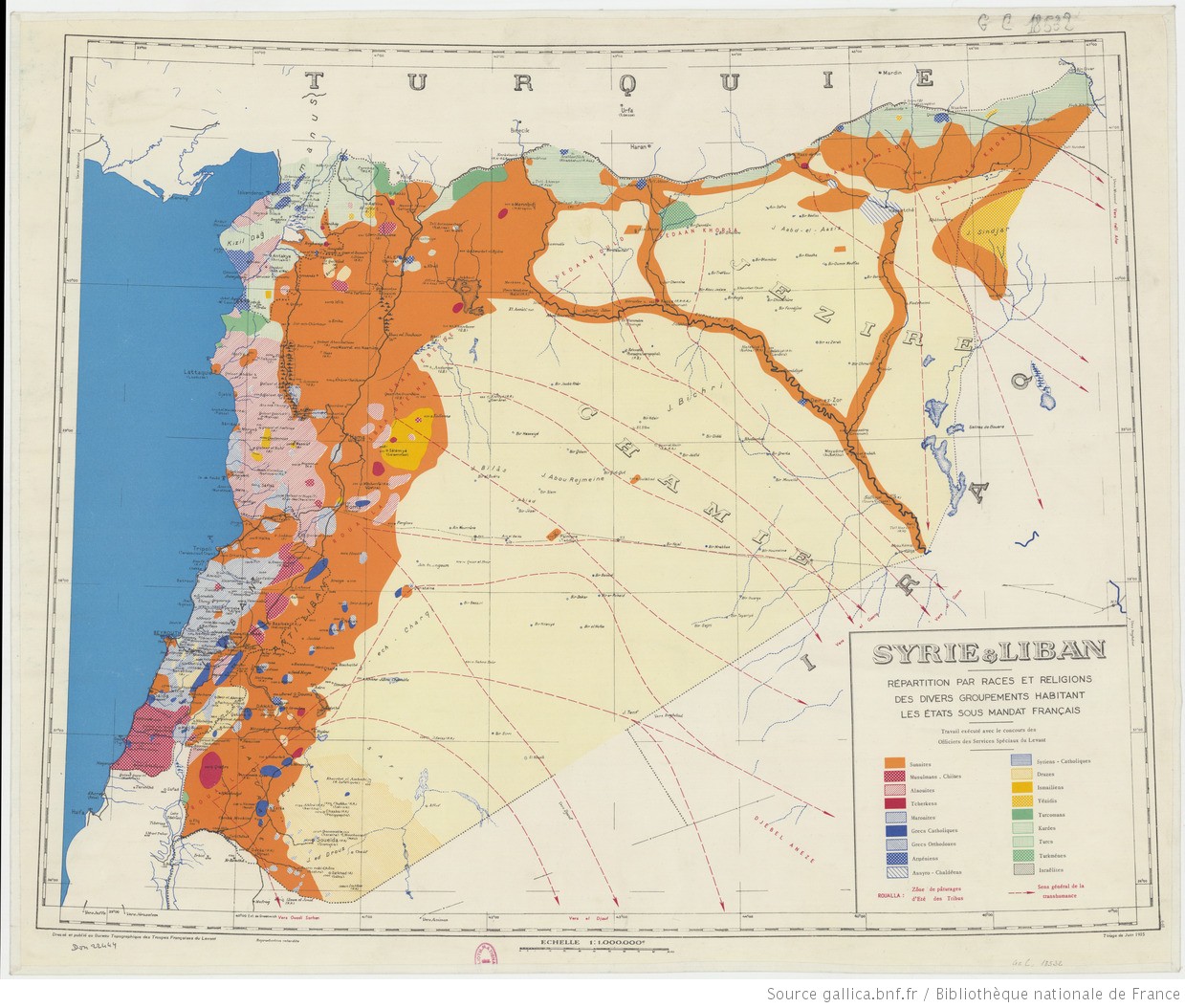

A map showing ethnic and religious distribution in Syria and Lebanon under French mandate. Source: Gallica

The Ezdina Foundation states that there were 200,000 Yazidis in Syria prior to 2011, according to unofficial statistics. However, their numbers decreased considerably during the Syrian war.

The Yazidis are located in Afrin and Aleppo, as well as in the Jazira region, specifically in al-Hasakah, Qamishli, Amuda, Ad-Darbasiyah, Ras al-Ain (Sere Kaniye), and al-Qahtaniyah (Tirbespi).

Ali Esau pointed out that Syrian Yazidis suffered agony as a result of the mistaken policies adopted by successive governments, seeing that they did not receive any constitutional recognition of their existence nor a law protecting them from abuse and extermination. These governments have not provided them with possible means to protect their religious affiliation and enhance their role.

Yazidis have also been excluded from participating in the political process, in addition to being denied access to parliament, marginalized, and not given any media, cultural, or social space aimed at promoting the spirit of civil peace.

The number of Yazidis in Syria has significantly diminished over the past years as a result of the afflictions brought upon them. As violations of their rights have recently worsened, and with displacement, their existence is threatened, which will be reflected on the wholesomeness of the varied mosaic panel that is Syria.

if you think the article contain wrong information or you have additional details Send Correction