Zainab Masri | Khaled Jeraatli | Hussam al-Mahmoud

Under the slogan “the unity of the Syrian people’s action,” the new president-elect of the National Coalition for Syrian Revolutionary and Opposition Forces —Syrian Opposition Coalition (SOC)— Salim al-Muslat reached for all Syrian political forces, calling for an overall collaboration to establish a democratic civil state capable of safeguarding the rights of all Syrians. He also renounced divide and stressed the need for teamwork as to improve the SOC’s performance.

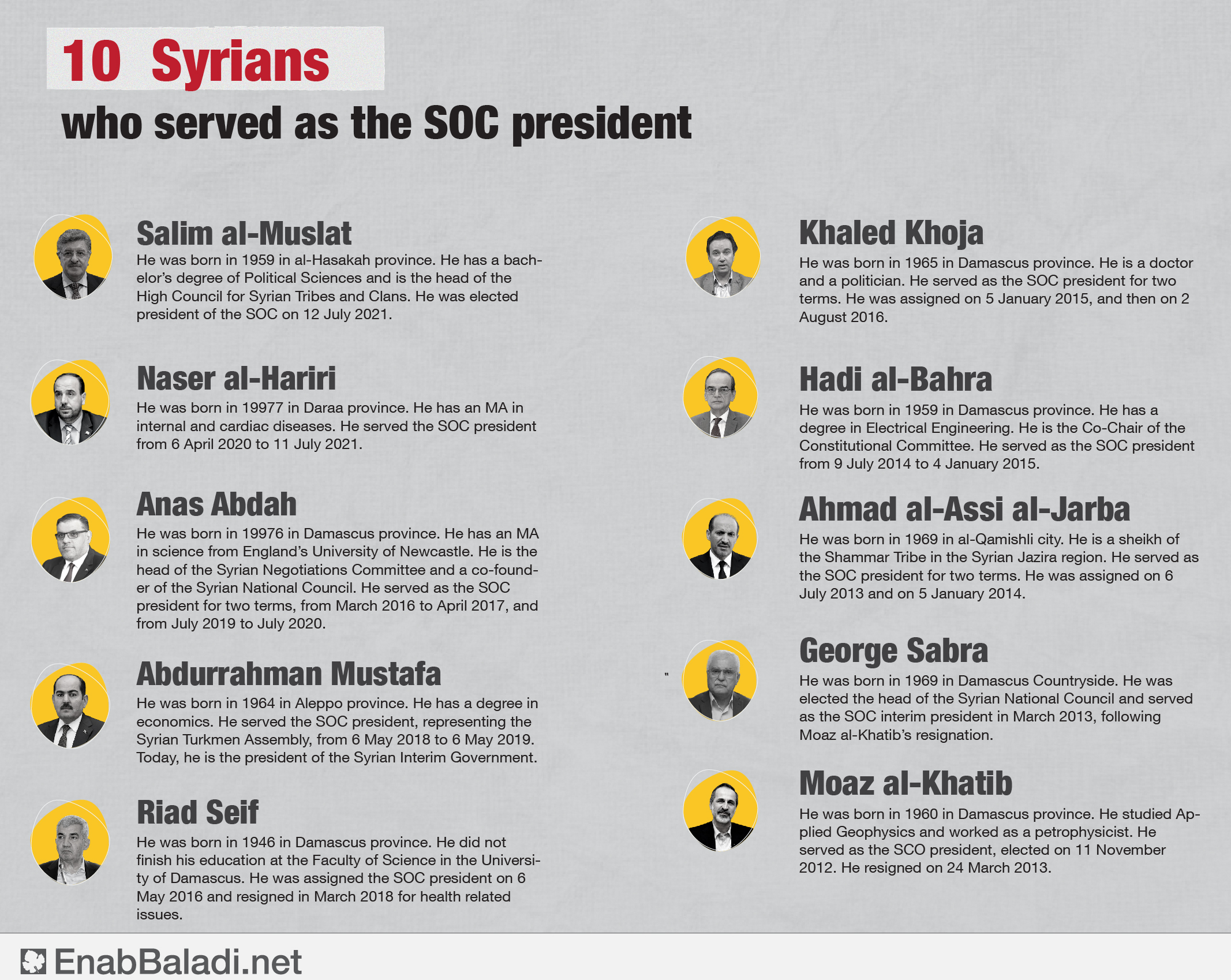

Al-Muslat won the 11 July elections, as the head of the High Council for Syrian Tribes and Clans, offsetting former SOC president Naser al-Harari, who announced during a press conference on 9 July that the SOC has documents leaked from one of the Syrian regime-affiliated hospitals. With all names recorded, the documents confirm the death of 5000 persons detained by the regime.

Al-Hariri said that only the SOC has these documents, being “the Syrian people’s sole representative,” oblivious that the representation he is referring to was never completely ratified by Syrians throughout the SOC’s political journey.

In the early years into its formation, the SOC attained partial recognition. It was even considered the official representative of the Syrian people in the League of the Arab States and some countries such as Turkey and Qatar. However, a large segment of Syrians held the SOC responsible for mismanaging and losing the political privileges it obtained.

The policies of the SOC are met with general discontent, particularly recently, following an incident involving a threatened journalist.

Based in the northern countryside of Aleppo, that journalist received an open threat for publishing an article criticizing al-Hariri’s policies, reported the Social Press Centre (SPC), where the article first appeared.

The resentment is apparent in the Syrian audiences’ reaction to the content posted onto the SOC’s social media platforms, even those relating to the SOC-provided services.

Followers often take to the comments section to criticize or insult whatever service projects the SOC attempts to start inside Syria.

In this in-depth article, Enab Baladi investigates into the reasons why Syrians refuse to acknowledge the SOC as their representative and discusses with political analysts the factors that stripped this political body of Syrians’ trust, as well as whether Syrians actually need a representative as such.

SOC going against its own convictions

On 11 November 2012, a declaration was made from the Qatari capital city Doha. A final agreement was announced as to unify the ranks of the Syrian opposition under the same entity; that is the National Coalition for Syrian Revolutionary and Opposition Forces.

The SOC’s formation agreement was signed after a week of talks that brought together personalities from across the Syrian opposition’s spectrum, Arab and foreign diplomats in Doha. The talks started on 4 November 2012, led by the back-then one of the larger Syrian opposition entities, the Syrian National Council (SNC).

The SOC then declared the Syrian Revolution’s Charter of Human Rights and Public Freedoms. The charter defines several key points that have been supposedly governing the SOC’s work since its establishment to the present day. The chief point was adhering to the slogan “One, one, one; the Syrian People is one!” Embracing this slogan was a reaffirmation of the Syrian people’s unison, including all its religious and national components.

The SOC’s adopted discourse addresses Syrians in the areas held by the opposition, regime, and de facto authorities, as well as in countries of asylum. The SOC calls for “a national alignment whose objective is to save homeland; face the serious challenges it is encountering; safeguard its geographical, political, and social unity; set in motion all forms of revolutionary action and popular resistance, including the removal of foreign forces, cross-border sectarian militias; and combat any compromises of homeland’s sovereignty and its interests or tampering with its culture, language and creeds.”

However, a recent wave of criticism hit the SOC on the heels of official statements that breach the core of the charter and the discourse.

The last of these statements were made by the former SOC president al-Hariri. He called Turkey to militarily intervene against the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) to remove it from the cities of Manbij and Tall Rifat.

The backlash was from within the SOC. The Kurdish National Council (KNC), one of the SOC’s bodies, considered al-Hariri’s calls a “violation of the Syrian State’s sovereignty, a breach of the Syrian revolution’s principles and values, and an abuse of the ties between the [SOC’s] components.”

The KNC made a counter-statement in June. The KNC said that al-Hariri’s calls for the Turkish presidency to militarily intervene in other Syrian areas contradict the SOC’s objectives that seek to realize freedom for the Syrian people and safeguard its stability and dignity in a sovereign, free and democratic state.

Furthermore, the SOC’s mission statement defines its goals as to unify political and military bodies and “to establish a transitional government after receiving international recognition.”

Pertaining to the transitional governing body, the SOC’s relationship with the Syrian Interim Government (SIG) remains unclear, amidst reported ongoing disputes between the two.

These disputes lost momentum because the SOC failed to establish a transitional government, denied recognition, aside from Turkey and Qatar, and later losing the acknowledgment of some of the European and Arab countries it obtained in earlier years.

Is the SOC really needed?

The SOC’s claimed discourse defines it as “the legitimate representative of the Syrian people,” underscoring that the SOC is not an opposition-specific institution, nor exclusive to the revolutionary forces.

The SOC also holds the belief that it is responsible for all Syrians, regardless of their positions or stances, and that its goal— to achieve a comprehensive and fundamental change of the existing regime and establishing a democratic alternative one— goes beyond the pro-revolution Syrians and opposition forces, applying to the entirety of the Syrian people.

The SOC stresses that its discourse addresses all Syrians, inside and outside the country.

To gain insights on the course of that SOC’s work under its declared guiding principles Enab Baladi spoke to the Syrian researcher and political analyst Naser al-Youssef.

Analyst al-Youssef said that any collective action, such as the Syrian revolution, needs a conscious leadership to guide its course. When it first started, the SOC was one of the institutions that possessed this trait, but when several of its members turned matters of importance into personal-interest-affairs, the SOC lost its privilege as such a leader.

He added it is indisputable that chaos is the alternative to order. The purpose of establishing institutions to lead or represent major causes is to set these causes into order. The absence of order and these institutions’ assent to their donors’ instructions have ultimately resulted in chaos. Chaos does not ever have a positive impact.

He said that the SOC had access to political gains that positively influenced its formative years and the corresponding political phase. The SOC attained the recognition of about 120 countries as a legitimate representative of the Syrian people and was thus granted a set at the League of Arab States, from which the regime was excluded.

Al-Youssef reiterated that those gains were positive and effective; however, they were lost over a time shorter than the SOC took to obtain them.

The loss, he attributed to “opportunism and selfishness” within the SOC that eventually pressed some countries to revoke their recognition or consider recognition wrong even though they did not express that opinion openly.

Al-Youssef believes that the SOC had an adverse influence on the Syrian revolution, but he did not encourage stripping it of its role as one of the revolution’s political representatives.

He even said that isolating the SOC is not in the revolution’s best interest, suggesting that “replacing [its members] and reforming it is the best choice considering Syrians’ interests.”

He added that the political faces “we have repeatedly seen and known over the past nine years” have to make room for new personalities and elements. New elements must be introduced instead of shuffling the SOC positions among the same politicians who all had experiences that harmed the struggle of the Syrian people.

Al-Youssef stressed that the principles by which the SOC is functioning should also be revised to reflect the current stage of the Syrian cause.

Enab Baladi also discussed the factors that caused the SOC to fail in playing the role it assumed with the researcher at Jusoor for Studies Wael Alwan.

Researcher Alwan said that the “large-scale revolution” that the Syrian people embarked on needed a political representation that could make use of all available local and external political resources to fully develop an inclusive national project that responds to Syrians’ goals and their just demands.

Instead of such a representative, Syrians got a body that “failed to effectively bring together the Syrian political elites,” enabling thus ongoing rifts and divisions, he added.

He said that the SOC also did not succeed in establishing the “national project” that Syrians needed as a center to come around, pointing that the SOC’s performance defined it as an institution created by the international community to be the regime’s counterparty during the solution-seeking political process imposed by negotiations.

He added that the SOC truly preserved the revolution’s principles in its statements and declared positions, but it failed to provide a representative political model. The SOC, as an institution, has to be a platform for the activities of the Syrian political elites who are working towards an inclusive Syrian national project.

Alwan stressed that abandoning the SOC would not be advantageous to Syrians, because there is an urgent constant need for using all the resources the Syrian opposition has, including elites and resources, to develop and modify them based on a clear national project that expresses the Syrians’ need for freedom, justice, and new regime built on transparency and peaceful transfer of powers, as well as the application of democracy, not only alleging it.

No military strategy

In a 2013 research paper titled “The Syrian Opposition’s Leadership Problem,” Yazid Sayigh argues that “the National Coalition, which has supplanted the [Syrian National Council] SNC, has proved no more effective in providing strategic political leadership, empowering local civil administration, asserting credible authority over armed rebels, delivering humanitarian relief, and devising a political strategy to split the regime.”

Sayigh adds that “expecting funding and political recognition from the international community, opposition figures and factions in exile competed for status and resources rather than uniting under a common banner.”

He proposes that “[the SOC] must empower the grassroots structures to become the opposition’s real political leadership inside Syria and shift its focus to frankly engage key political constituencies and state institutions to split them from the regime if it hopes to bring about lasting, democratic change.”

He also investigates the SOC’s lack of military strategy, comparing the SOC’s military stance with the former SNC’s strategy. According to Sayigh, “since its formation, the SNC had opposed external military intervention in Syria and arming the opposition, but in February 2012 it reversed its position. Publicly, SNC leaders made this their central demand, but privately, they acknowledged that military intervention would not happen.”

Sayigh posits that the SOC was founded to reform the unsuccessful SNC’s military strategy, also failing to link the military dimension of the revolution with its political dimension. He says the SOC was ultimately a clone of the SNC’s experience, leading only to the same previous outcomes.

Eventually, the revolutionary military strategy was all about two major military factions in charge of the opposition-held areas. These are the Syrian National Army (SNA)—representing Turkey’s policy for the area, even if relatively—, and the Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS)—designated as a terrorist group, and constantly advocating its own enterprise that represents it in the media and is radically different from the happenings on the ground across the Syrian map.

The HTS had founded its own political body; namely, the Syrian Salvation Government (SSG), which has been disrupting the SIG’s projects in key areas in northern Syria, including Idlib and its suburbs, sparing only education-related projects which the area’s civil society organizations have been operating for the most part.

Administrative dilemmas

Over the past years, the SOC was a frequent subject of controversy, given that it is the opposition’s political body voicing the Syrian people’s struggles and difficulties. Those discussing the SOC’s course of action would wonder about its role in creating these difficulties, as well as its ability to address them, while Syrians hoped for civil institutions, full of the revolution’s spirit, transparent, and pure of routine and bureaucracy that mark regime-operated institutions.

Certificates forgotten on shelves

Of the key matters that the SOC is criticised for is the time-consuming process that Syrians have to go through to get their education-related documents certified, as a prerequisite for applying to Turkish schools and universities.

The documents are certified by the Citizen Service Centre the SIG— the SOC’s executive wing— opened in Gaziantep, in Turkey, in 2016.

Turkey-based Syrian refugees’ certification applications are often met by delays and procrastination, causing many to lose a school year. Several Syrian clients have even lost documents after they handed them to the center, highlighting the center’s irresponsibility.

In a previous report, Enab Baladi interviewed a number of Syrian refugees who sought the center to certify documents. One such interviewee, Alaa al-Din, a student living in Turkey, pointed to the difficulty of keeping up with the center’s requirements, adding that the “Citizen Service Office tends to impose . . . unrealistic conditions.”

The certification of documents remains one of the most urgent issues. This proceeding controls the fate of students and their ability to pursue their education, threatening to leave them out of schools, which is the tragic situation that numerous Syrian students fell to over the course of the Syrian conflict.

Fake passports, or ones that take you nowhere

In addition to administrative procrastination, the SOC-affiliated embassy in the Qatari capital Doha is accused of issuing fake passports for opposition-linked personalities.

The issue of fake passports is often discussed in relation to the SOC’s attempts at making a trade of such official documents or to smuggle wanted people to Turkey. The SOC refuted these allegations in a statement on 24 October 2018.

The statement read, “what media outlets have been publishing regarding fake passports issued by the embassy in Doha, with official markers, intending to facilitate smuggling or transferring some wanted terrorists to Turkey, is entirely false.”

The statement was a response to photos published by the local Sham FM radio, claiming they are of a Syrian passport issued with the name of a female Emirati opposition personality.

The radio cited a source from the Syrian Department of Immigration and Passports as saying that the said passport’s number belongs to a Syrian citizen and that the Emirati personality used that passport to travel from Qatar to Turkey.

The SOC attempted to issue Syrian refugees passports through its offices in Turkey and Qatar. However, it failed to bestow on these passports a sense of credibility because no countries were truly willing to recognize the legitimacy of the SOC, former SOC president, Naser al-Hariri said once.

Al-Hariri, back then head of the Higher Negotiations Committee, admitted that thousands of passports were issued in Turkey, which were ultimately exposed as being fake.

The former SOC Secretary General, Nazir al-Hakim, was held accountable for the passports, for several of these passports’ holders were arrested at different airports on charges of official document forgery.

Al-Hakim’s Istanbul-based office issued approximately 37,000 persons fake SOC passports, who were all prosecuted, according to the statement of an Avaaz-mediated campaign, which demanded the arrest of al-Hakim on the charge of “fraud” and issuing fake passports.

Medical malpractice

In September 2014, 15 children died in the town of Jarjanaz in Idlib countryside. During a measles vaccination campaign, Atracurium was administrated to children instead of the correct solvent for the rubella vaccine.

At the time, the SOC responded by the dismissal of the SIG’s Minister of Health, Adnan Hazouri, and several workers of the SIG’s health departments and the Assistance Coordination Unit (ACU), as well as the head of the ACU, Suheir Atassi, who protested the dismissal decision and was shortly reassigned.

In March 2015, Atassi resigned from her position as the ACU’s head, two years after assuming office.

On her personal Facebook page, Atassi defined the reasons that made her resign, saying she has offered all she could in the past two years.

Activists and pro-opposition personalities repeatedly accused the ACU, founded by the SOC in December 2012, of corruption. Additionally, the financial accounting and operations – Deloitte Firm said it had reservations regarding a million USD that did not appear anywhere in the ACU’s 2013 data.

Wholesale resignations

In parallel with on-ground struggles, the SOC had several intra-administrative challenges to overcome, particularly mass staff resignations in April 2018.

Given the divergent political stances of its members and also the SOC’s lack of adherence to the goals it defined when founded in 2012, George Sabra and Suheir Atassi resigned, in addition to Khaled Khoja, who attributed his withdrawal from the SOC to the same reasons that Sabra and Atassi have both referred to.

Defining the reasons for his resignation, presented to the SOC president and members of the General Assembly, Sabra said that the SOC “is no longer the coalition born in November 2012, shouldering the responsibility of remaining loyal to the principles of the revolution and goals of the people.”

He added that the SOC’s working measures and adopted approaches do not respect documents or decisions, ungoverned by the SOC’s members’ will or the independent Syrian national vision, not forgetting the existing contradictions among its components and members.

For her part, Atassi said that she opted for the resignation because the official institutions of opposition and revolutionary forces have lost the challenge imposed by the international community.

She added that involved states have put the opposition’s bodies before binary options, either to succumb or diminish. Some have prioritized survival and coping with the situation; others were cracked and lost the sense of institutionalization, fragmented into several entities that openly fire contradictory political statements against each other.

When it was established, the SOC presented itself as an umbrella for the opposition against the Syrian regime. However, it was met with widespread criticism and accusations related to its political performance and its failure to accommodate all spectrums of the opposition.

if you think the article contain wrong information or you have additional details Send Correction

النسخة العربية من المقال

-

Follow us :

Elections of the Syrian National Coalition’s president and members of Political Committee (Edited by Enab Baladi)

Elections of the Syrian National Coalition’s president and members of Political Committee (Edited by Enab Baladi)

A

A

A

A

A

A

More In-Depth

More In-Depth