The guard is also the thief: Why is Russia so interested in the Syrian cultural heritage?

Amal Rantisi | Diana Rahima | Ali Darwish

“States should remember that the guardianship of culture is their duty and not a right. It is a duty to protect Palmyra, the monasteries of Maaloula, the mausoleums of Muslim saints in Syria and Iraq, Mali. That is what Russia is doing today. Not for the first time. For us Palmyra is a great image – a parallel to St Petersburg for beauty. It appears on the covers of textbooks. Many Russians have their children baptized in Syrian monasteries. It is our heritage too,”

Mikhail Borisovich Piotrovsky, Russian orientalist and General Director of the State Hermitage, said in a speech delivered in 2015 after the Islamic State (IS) destroyed monuments in the city of Palmyra, east of Homs governorate.

Piotrovsky’s earnest speech had several dimensions to it, highlighting the intensity of Russia’s interest in Syria’s cultural heritage. Many such official statements followed, speaking about “protecting, tending to, and restoring” Syrian antiquities and archeological sites, destroyed or vandalized during active combat.

However, Russia’s interest was not limited to official statements. Russian experts have already restored some archaeological site, photographed or digitally blueprinted others, preserving the footage for later use.

This increasing interest makes cultural heritage the fourth domain— besides politics, economy, and military— that Russia has established control over since they first announced their intervention in Syria on the side of the regime in 2015.

The Syrian concerned authorities, in their turn, have been denying archeological teams from countries, that made human rights violations the center of their stand against the regime, the renewal of their credentials, granting Russian archeologists almost exclusive authorizations and privileged access to Syrian archeological sites.

In this article, Enab Baladi sheds light on Russia’s growing interest in the Syrian cultural heritage and Moscow’s current and future gains from managing heritage affairs, as well as the role of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), as an authority on culture worldwide.

Heritage: Russia’s next target in Syria

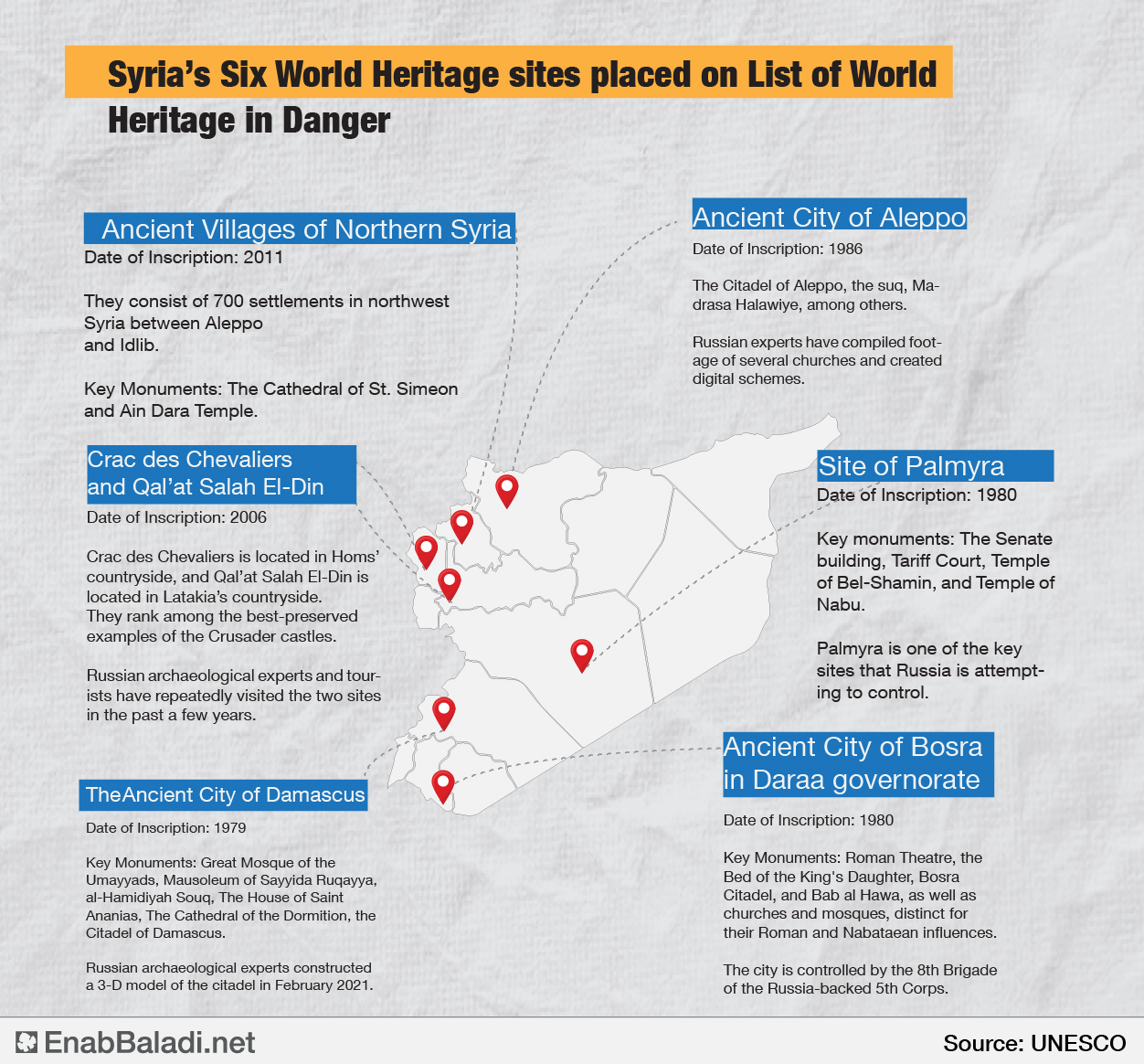

Over the course of the Syrian conflict, heritage too became a victim, including over 10,000 archaeological sites. About 3000 of these are inscribed on the national heritage list, and six on the World Heritage List.

Since 2011, which marked the start of unrest in Syria, archeological sites have been tragically destroyed, vandalized and pillaged. Artillery shelling and airstrikes by regime forces and Russian allies, or confrontations between different parties to the conflict decimated many sites; others were vandalized for political or ideological reasons. Artefacts were stolen by regime-affiliated para-militaries or the IS, causing illegal antiquities trade to flourish.

In reaction, UNESCO, with funding from the European Union (EU), launched many projects to protect the Syrian heritage, including the Emergency Safeguarding of the Syrian Cultural Heritage project.

The project seeks “to provide an operational response to halt the on-going loss of cultural heritage and prepare post-conflict priority actions in Syria.”

The project also aims to put in place mechanisms to protect remaining artefacts, assist in detecting looted or destroyed artefacts, prosecuting those involved in illegal antiquity trade and bringing them before international law.

Nevertheless, such justice-seeking efforts have many challenges to overcome. It remains hard to prosecute violators of antiquities laws, given the great corruption involved and the many suspicious deals realized at the expense of heritage.

Furthermore, access to archeological sites is particularly difficult due to the complex nature of the security situation in Syria, while concerned local activists and lawyers are equipped with little to no knowledge of international law’s working methods.

Russia politicizing heritage

The situation being thus, Russia is planning to use heritage for two simultaneous ends. It seeks to engage itself in post-war Syria and normalize its relations with the West away from the political sphere that has become extremely complex.

Director of Idlib Museum, Ayman al-Nabu, told Enab Baladi that antiquities, for countries that “respect themselves”, are an issue of sovereignty. However, in Syria the situation is largely different given the Russian intervention.

The antiquities’ relevance to sovereignty stems from the fact that archeological sites and artefacts are a part of a country’s historical roots and civilizational identity. Therefore, they are often covered by the media and used for propaganda purposes. It is along these lines that Russia has been investing more efforts in the domain of the Syrian cultural heritage.

Al-Nabu added that antiquities would be of the core domains to be addressed by the future reconstruction processes, in terms of restoration and architectural and artistic rehabilitation of archaeological sites, as well as developing a tourism-based approach in Syria. To these ends, large sums of money would be invested in the antiquities’ domain.

He added that Russia is well aware of this and this why extra efforts are being made to control the Syrian heritage affairs.

In a February 2020 article, “Russia’s Next Target in Syria? Its Heritage,” OZY magazine posits that “ancient history may be Russia’s latest route to gaining influence in the Middle East.”

In another article, “Violins and trowels for Palmyra: Post-conflict heritage politics,” Gertjan Plets, anthropologist and Assistant Professor in Cultural Heritage at the Department of History and Art History at Utrecht University, argues that “Palmyra is very important for the Russians. It is constantly being used by the media in its depictions of the war in Syria.”

Plets’ research reveals that “since 2017, RIA Novosti, Russia’s state-owned domestic news agency, has published 31 feature articles on Syrian heritage alone as part of a broader effort to legitimize Moscow’s involvement and troops in Syria to the Russian public.”

OZY magazine also stresses that “while most international archaeological teams from countries whose governments oppose the regime of President Bashar Assad have seen their Syria credentials expire, Russian teams and archaeologists have been allowed to work at some sites, at least in Palmyra and Aleppo.”

No coordination: re-discovering the discovered

Russia’s interest in the Syrian cultural heritage has been the subject of wide criticism, with followers arguing that Moscow is attempting to boost its political gains at the disadvantage of heritage, pointing also to the Russians’ tendency not to coordinate with the Syrian local authorities, represented by the Directorate-General of Antiquities and Museums.

One of the striking incidents as to the lack of such coordination is the agrological discovery announced by Dmitry Tatarkov, the director of the Centre for Marine Research and Technology at Russia’s Sevastopol State University (SSU) on 28 January 2021.

Tatarkov announced that a Russian-Syrian expedition discovered an ancient port believed to date back to the Roman-era off the Syrian coast of Tartous.

The announcement seems to have been released without prior coordination with the Syrian relevant authorities. The Director-General of the Syrian antiquities directorate, Nazir Aw, said that the directorate and the Tartous Department of Antiquities were both waiting for a detailed report from the Russian team concerning the discoveries, while both teams had to discuss the means for reporting any related information.

Syrian archeologist Saad Fansa, who worked for nearly 30 years with the Damascus National Museum and the former director of the Department of Photography and Archives of Syrian Antiquities, told Enab Baladi that this port was already discovered by a French team decades ago, and its initial defining characteristics, as well as the era to which the remains of the building belong, were identified. The port belongs to an era during which the Kingdom of Arwad prospered, maintaining control over all the ports of the ancient Phoenician coast.

However, the hasty account given by the Russians about the history of the port “confirms that the authors of the research have nothing to do with the history of Syrian antiquities, and are not archaeologists in the first place, and that all these ongoing works today are a cover for the search for wealth and treasures,” Fansa said.

Fansa criticized the absence of a national decision, considering that decision-making belongs to the Russians today, adding that the Syrian heritage issue is a small file in a complex and more essential set of files administrated by the “Russian mafia.”

Russian gains from interest in Syrian antiquities

For decades, due to lacking national expertise, European experts have been consulted on the Syrian antiquities’ domain and the work it involved.

Fansa told Enab Baladi that, historically, it was the Europeans who supervised the restoration and excavation work in Syria. Furthermore, with EU funding— from France, Italy, Switzerland— automation systems were introduced to the Syrian departments of antiquities and museums, which thus started to digitalize some of the restoration projects and work at archeological sites.

Today, Russia has established their hegemony over Syria’s resources with Bashar al-Assad’s full consent. One of the chief gains that Russia can achieve from handling the affairs of Syrian antiquities is symbolic, polishing their cultural profile on an international level.

More important yet, Russia seeks to have access to funds provided by international organizations, including UNESCO. These funds are lucrative sums of money often designated for the administration of internationally protected archeological sites under a decision from the UN agency. These donations have been falling into the pockets of corruption networks thriving under totalitarian regimes, which lack a minimum of transparency while always escaping accountability, said Fansa, co-founder and board member of the Al Adeyat Archaeological Society dedicated to protecting artefact and archeological sites in Damascus.

Furthermore, discovering new archaeological sites might feed Russian museums with a new set of artefacts.

The Syrian journalist and defender of Syrian antiquities, Omar al-Buniya, said that there two reasons for Russia’s efforts to establish hegemony over the antiquities file in Syria. First, Russia seeks to trade with artefacts from Syria. Second, they seek to control the restoration funds, provided through large-figure contracts from UNESCO or other international organizations concerned with heritage protection.

Enab Baladi sent UNESCO asking for a comment on their Syria heritage funding policies and recipients.

UNESCO’s replay was limited to highlighting their funding channels, saying that financing is managed through the World Heritage Fund projects and the international aid projects listed on its website.

UNESCO -funded heritage projects

Between 2011 and 2021, UNESCO has financed three projects with 90,000 USD, according to the international assistance projects listed on its website.

- Safeguarding the Damascus Wall and the adjacent Urban Fabric (the area between Bab al-Salam and Bab Touma)

Decision Date: 29-Oct-2020

Amount Requested: 30,000 USD

Type: emergency

Modality: Technical Cooperation

Category: culture

- Documentation & Emergency Structural Intervention in Qa’lat Salah El-Din

Decision Date: 03-Mar-2020

Amount Requested: 30,000 USD

Type: conservation

Modality: Technical Cooperation

Category: culture

- Recovery plan for Ancient City of Bosra

Approved Amount: 30,000 USD

Decision Date: 21-Dec-2018

Amount Requested: 30,000 USD

Type: emergency

Category: culture

Al-Buniya said that restoration funds from UNESCO all go to Russia, the antiquities directorate, and Russian companies that are implementing restoration contracts.

In November 2019, the Russian oppositionist website ZANK stated that Russian tourists had started traveling on vacation to Syria, paying over 100,000 Russian rubles for the tour.

Vacationers are flown to Beirut by the Russian tourism companies Kilimanjaro and Miracle, and then transported to Syria by land.

For the 8-day-tour, groups visit Damascus, Maaloula in Damascus suburbs, Aleppo, Hama, Krak des Chevaliers in Homs, Palmyra.

According to BBC, “following media reports about the tours, the Russian Federal Agency for Tourism issued a recommendation to all tour companies to stop offering trips to Syria, and advised Russian tourists to avoid trips to the country until ‘the normalisation of the situation’.”

For his part, the Syrian expert in Russian affairs, Dr. Mahmoud Hamza, told Enab Baladi that the Russian interest in Syrian antiquities and the multiplicity of statements about the issue are all efforts aimed at “polishing [Russia’s] image” and benefiting from the Syrian scientific and cultural domains.

The Russia-based expert Hamza traced a link between the Russian statements on Syrian antiquities and former statements on their military intervention. The statements matched in the sense that they indicated that the Russians are coming to “liberate” the country from IS, and that Moscow “did not enter [Syria] as an occupier or supporter of the regime,” as much as to do something humanitarian that is in the favor of humanity.

In his research, Plets argues that the restoration of archeological sites in Syria is not a direct competition between Russia and the West over the culture of Syria. On the contrary, Russia’s attempts to engage international teams in UNESCO-funded projects in Syria, suggests “it is geared towards internationally legitimizing Assad and his Syrian Arab Republic.”

Opinion poll: for Russia, political influence comes first

Enab Baladi conducted an online survey on its website and social media platforms, asking the audience for their opinion regarding the increasing media coverage of Russian antiquity restoration and excavation work in Syria.

Of 400 respondents, 76.2% voted that these activities are aimed at boosting the Russian political influence in Syria; the remaining 23.8% voted that Russia has genuine archeological interests.

Beginning in Palmyra:

The course of the Russian archeological activity

In 2016, Russia urged UNESCO to help restore the vandalized ancient city in Syria.

In May that year, the former Russian Deputy Foreign Minister, Gennadij Gatilov, met the UNESCO Director-General, Irina Bokova, to discuss the UN agency’s response, and requested assistance to Syria in restoring the destroyed monuments in Palmyra.

Gatilov, during a session of the Executive Council of UNESCO, according to the state-run Syrian Arab News Agency (SANA), called upon “international experts to head to Palmyra soon, and asserting the need for the UNESCO to monitor the situation in Palmyra and send a team of international experts to estimate damage as soon as the city is totally secured.”

In the past few months, Syrian archeological sites have been making headlines in Russian media. Enab Baladi monitored various coverages addressing ancient cities, museums, and churches.

On 8 June, the Russian RT TV channel covered the restoration of a church in Aleppo.

The channel quoted the Deputy Director of the Institute for the History of Material Culture of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Natalia Solovyova as saying that at the end of their work they managed to “construct a 3-D model, as a geographical information system and electronic archive.”

The model recounts the story of historical and cultural monuments, and related archival materials, which would be presented before the international community, Solovyova added.

To construct the 3-D model, Egor Blokhin, a researcher at the Institute for the History of Material Culture of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Russian experts used drones to film the archeological sites, which are then processed and turned into the multidimensional model. Experts also measured the temperature of stones and located weaknesses of the sites’ structures.

On 2 May, RT reported that Russian archeologists launched a project to assess 10 churches in the city of Aleppo dating back to the early Middle Ages. The project involves taking pictures and filming these sites and then turning them into 3-D models and calendar charts for the areas in which these churches are located.

In February, TASS news agency reported that Russian experts created 3-D models of the Citadel of Damascus and of Palmyra city.

On 12 April, the Palmyra Restoration Fund announced that the restoration of the Arch of Triumph in the ancient city of Palmyra, east of Homs, would begin in 2022.

The Palmyra Restoration Fund was established by Russia to raise funds for the restoration of the city of Palmyra, in cooperation with a number of international bodies and museums.

The restoration plan consists of three stages: documenting the damage, studying the damage to come up with an estimation of the restoration costs, and then restoration, according to the Russian Interfax agency, quoting the Executive Director of the Fund, Sergei Titlinov.

Last March, TASS news agency said that a Russian company is working on a digitalization project, creating digital lists of the archeological sites in Syria.

The agency quoted the head of the department of interaction with educational institutions of the Geoscan group, Oleg Gorbunov, that the company intends, in cooperation with historical institutes, to digitize ancient and archaeological sites in Syria, and work will start in 2021 if conditions permit.

Gorbunov added the major artefacts were filmed in the city of Palmyra in the eastern countryside of Homs, but experts might refilm the site to expand the scope of the project and include other locations. Indeed, similar work was carried out in Aleppo and Damascus.

Does Russia have enough experience?

Activist al-Buniya said that Russia has little experience in archeology, former missions that worked in Syria were American, French and German.

He added that a single Russian expedition operated in Syria in the Tell Khaznah site, northeast of the city of al-Hasakah. The expedition did not discuss their work or publish research or any other findings.

French historian and archaeologist Annie Sartre-Fauriat, who has been working on Palmyra for over 40 years, told Deutsche Welle in 2016 that “I’m worried about the situation because the Russians have no experience when it comes to Palmyra. They lack the expertise to carefully and respectfully restore the World Heritage site.”

“The Russians have never been involved with the Palmyra site, not as archeologists, not as historians, nor as conservators,” the expert added.

“In my opinion, it’s simply a political maneuver. Putin only helped al-Assad recapture Palmyra so that he could be celebrated as a savior, and the Assad regime gladly made use of his help,” she said.

In its response to Enab Baladi, UNESCO said that “Please note that the Russian Federation is one of the 21 members of the World Heritage Committee and has expert teams at their disposal.”

“Furthermore, the Hermitage in St Petersburg contains the largest museum on Palmyra outside of Syria and Russian specialists work in this regard for a long time. They also participated in relevant workshops organized by UNESCO,” the UN agency added.

Additionally, the agency said that “UNESCO collaborates with a number of partners and exchanges on the safeguarding of World Heritage sites with the advisory bodies ICOMOS and ICCROM, but also for example with the Aga Khan Trust on Aleppo, or with UNITAR on the analysis of satellite images, as well as civil society organizations end experts including of the Syrian diaspora.”

What does the Syrian law say?

Lawyer Ahmed Sawan has previously discussed with Enab Baladi the penalties for smuggling and illegal excavating for artefacts.

The law treats these practices as having a criminal nature, which deserves a harsh and deterrent punishment that equals the penalty for murder under Syrian law.

Article 56 of the Syrian Antiquities Law stipulates that “whoever smuggles antiquities, or attempts to smuggle them, shall be punished by imprisonment from 15 to 25 years and a fine of five hundred thousand to one million Syrian pounds.”

As for the penalty for excavating antiquities without a license, it is stipulated in Article 57/2 of the Antiquities Law, which states that “a penalty of 10 to 15 years imprisonment and a fine of one hundred thousand to five hundred thousand Syrian pounds shall be imposed on anyone who conducts antiquities excavations in contravention of the provisions of the law.”

The Antiquities Law defines excavation “as all works of excavation, probing, and investigating in search of moveable or immovable antiquities deep in the ground, on the surface, in water valleys, lakes, or territorial water.”

Those involved in antiquities trafficking, according to Article No. 57c, are to spend 10 to 15 years in prison, in addition to paying a fine of 100,000 to 500,000 Syrian Pounds.

Local and international laws on antiquities aim to protect and preserve them from tampering, vandalism and theft.

Discussing the Syrian Antiquities Law, Fansa said that the law granted wide powers and facilities to archaeological research bodies and centers, and was clear on banning transporting artifacts discovered by foreign missions outside Syria, except for study and examination, and on the condition that they are returned to national museums at the end of the study process.

However, he said, many archaeological artefacts were transported and never returned, given that the antiquities directorate doe does not have real powers and is subject to a higher authority legalized by the Assad government, that has been perpetrating thefts. Many security officers in Syria have prided themselves on owning artefacts stolen from archeological sites under the eyes of these “caricature antiquity authorities.”

if you think the article contain wrong information or you have additional details Send Correction

النسخة العربية من المقال

-

Follow us :

A

A

A

A

A

A

More Investigations

More Investigations