Zeinab Masri| Nour al-Din Ramadan |Sakina Mahdi

“Live by what you have got” is the rule that governs Abdulfatah Najim’s household budget. But how much has he got as an employee in Raqqa city, northeastern Syria? And given the area’s abundance of agricultural, livestock, and water resources.

Despite the plenitude of resources, families in territories run by the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES) can barely survive the economic crisis gripping the country as a whole. Najim had to design his budget on scarcity, like the rest of the area’s families due to the AANES’s economic and financial policies.

The AANES, established in 2014, stretched the scope of its power from military and security control to cover the economy, finance and the resources in the area where it holds sway.

In this extensive article, Enab Baladi investigates into the fate of the revenues of the area’s economic resources, discusses the financial and economic policies with which the AANES is managing these resources, and addresses the impact of these policies on the lives of citizens in northeastern Syria.

Salaries, prices, and the autonomous general budget

After the AANES approved pay raise to employees across its branch councils, administrations, and commissions, al-Najm received 260,000 Syrian pounds (SYP; about 90 US dollars) for his April salary.

Al-Najim, 35, told Enab Baladi that there is a huge gap between his assigned salary and the needs of his 5-member-family, adding that he often cuts off some of his family’s demands because he cannot catch up with the ever-spiking prices.

Ultimately, al-Najim had to have his minor son, 12, to help him. He opened a small shop where his son sells fuel and detergents to boost the family income.

Raqqa-based Jalal al-Muhammad, 30, is also unsatisfied with the daily wage he is paid for working with a construction crew. He is paid between 7,000 and 8,000 SYP (about three USD) a day.

Al-Muhammad called his wage “meager” because he is financially responsible for his wife, two toddlers, mother and father. However, he added that he is forced to accept working under these payment terms to provide the least of his family’s needs.

The accounts both the employee and the day worker gave to Enab Baladi do not reflect the plentifulness of the economic resources in the AANES-held areas, nor the returns of these resources, or the efforts that six administrative entities are investing in the economic sector.

On the condition of anonymity, an employee of the AANES Commission of Economy and Agriculture told Enab Baladi that salaries set up by the AANES are studied, adequate, and better of the pay range in the areas held by the Syrian regime or the opposition. He added that the AANES always seeks to improve pay based on the resources it has.

For his part, Issa, an employee in one of the AANES Finance Commission, said that the AANES can double existing salaries, but finance officials are against wage increase.

Going by a pseudonym, Issa refused to disclose the AANES’s justifications for not improving pay or economic conditions in its areas of control.

He, however, hinted that the AANES is investing the larger part of the resources’ revenues in the military to be able to defend the territories it controls.

He said, “the [AANES] has the right to channel the largest financial support to military forces to ensure its continuity and strengthen its administrative departments.”

The AANES raised salaries of its contracted employees by 30 percent as of early April.

Enab Baladi monitored salary and wage ranges in northeastern Syria. The AANES grants employees a salary ranging between 200,000 to 350,000 SYP (60 to 100 USD), while paying fighters of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) a monthly 500,000 SYP each.

Two-currency general budget

In April, the AANES Finance Commission approved a tax bill and ratified the General Budget.

On 28 April, the AANES General Council allocated 498 billion, 772 million and 350 thousand SYP (171 million, 599 thousand and 150 USD) to the general budget for the 2021 fiscal year.

The revenues of the general budget in 2021 are estimated at 206 billion, 540 million and 950 thousand Syrian pounds (244 million and 575 thousand USD).

Ibrahim Qis Ibrahim, a member of the Trade-Union Committee under the General Council, reported that the council divided the 2021 general budget into three main categories. The first is the existing operating budget, branching into three sub-budgets— the central budget (for the General Council, the Justice Council and the Executive Council); the local budget for the civil and autonomous administrations (legislative councils, regions, and autonomous and civil administrative departments); and salaries.

The second is investment budgets, designated for the AANES’s municipalities and councils. The third addresses the expected revenues, including central revenues and local revenues from the autonomous and civil administrations.

The central budget allocated to the AANES amounted to 48.39 percent, while the regional budget allocated to autonomous and civil administrations amounted to 51.61 percent of the general budget.

Ibrahim attributed the almost matching rates allocated to the two budgets—central and regional— to the fact that the central budget covers monthly salaries of nearly a quarter of a million employees, in addition to large investment projects in the SYP or the USD.

He added that the AANES has allotted a sum of money sufficient to cover salaries and pay raises for 7,000 employees till the end of 2021, indicating that this does not mean that the AANES will be hiring 7,000 employees, as it might recruit a smaller number.

He said that that the budget will be in the SYP and the USD because the AANES conducts procurements in USD and SYP alike, paying for imports in the USD. He added that domestic revenues are collected in the SYP while returns from external transactions are acquired in the USD.

The investment budgets of public entities are assigned by a bill from the Commissioner of Finance. Budget bills are approved by the relevant council that assesses the bill and its applications.

Aman waking along a water way polluted by an oil spill near the village of al-Sqairiyah in the countryside of Rmelan in al-Hasakah governorate, in northeastern Syria (Dalil Slaiman/ AFP)

“Primitive cash economy”

The General Council also obliged all public entities to transfer their revenues to the Treasury’s General Fund of North and East Syria.

“There is no or little available data on the budget revenue of the AANES, and it is particularly difficult to trace how it is collected and spent, partly because of the lack of transparency on this issue and partly because of the quasi-non-existent banking sector in the region,” according to a November 2019 researcher project paper, titled “The Political Economy of the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria”, by Sinan Hatahet.

“Despite the presence of state banks, the region is best described as a primitive cash economy. The AANES budget is financed through oil sales to the KRG [Kurdistan Regional Government in Iraq], the Assad regime and the local population; income tax and fees; and import duties,” the research highlights.

The nucleus of what would become the AANES was founded on 12 November 2013, and it was called the Constitutive General Council of the Joint Interim Administration. An offshoot of the council was a committee established to follow up on the project’s completion and draft various documents. The committee worked until the Democratic Autonomous Administration was officially declared as a governing body in three regions. The administration first pertained to al-Jazira region, claiming administrative powers there on 21 January 2014. In the same month, Afrin and then Kobani (Ain al-Arab) followed suit.

As the SDF controlled additional swathes of land, and finally Raqqa province in 2017, the areas were operated by as many as seven autonomous administrations, presiding over al-Jazira, Afrin, Euphrates, Manbij and its countryside, Raqqa, al-Tabqa, and Deir ez-Zor.

On 6 September 2018, the Syrian Democratic Council (SDC)—the political façade of the SDF—held a closed meeting in the town of Ain Issa, in the northern countryside of Raqqa, and announced the establishment of a Joint Autonomous Administration in Syria, the prototype of the existing AANES.

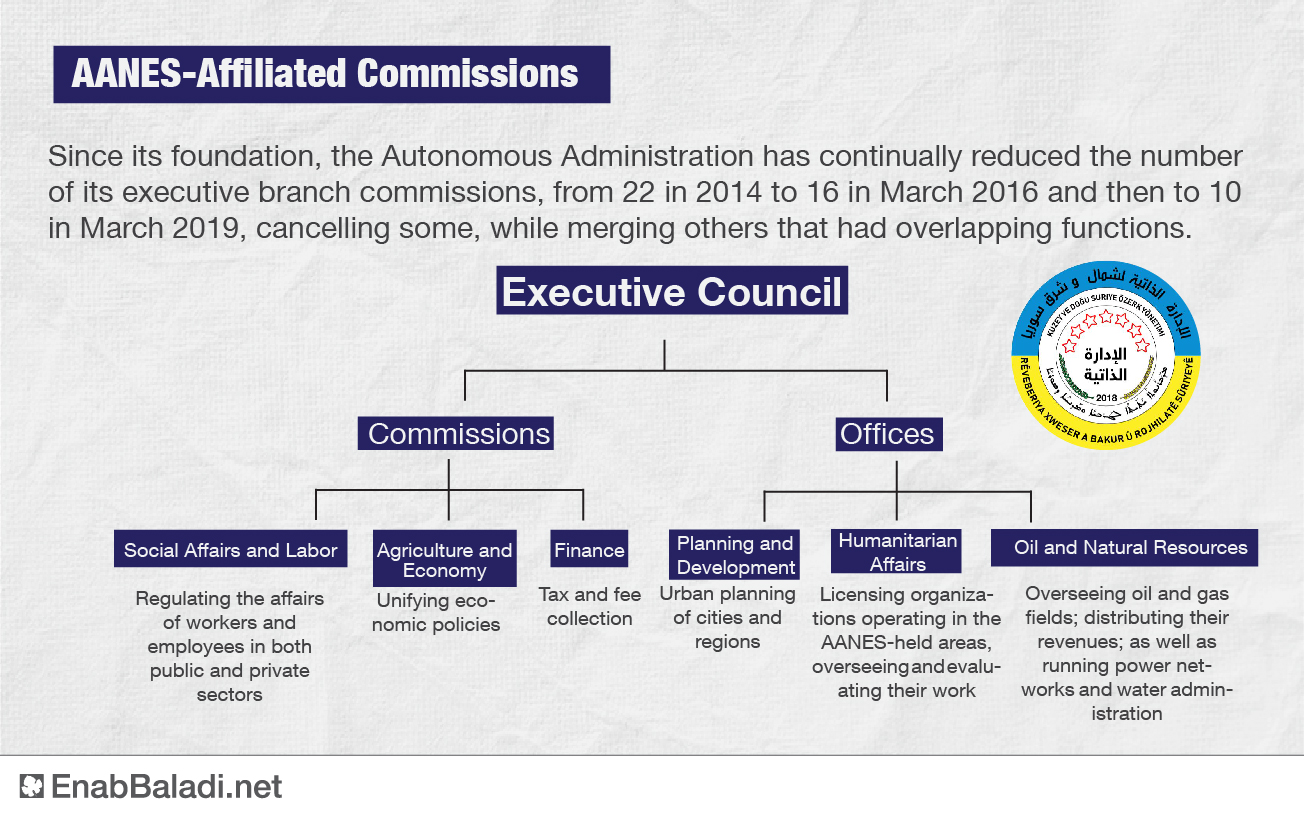

The AANAS constitutes of the General Council, Executive Council, and Legislative Council.

These councils operate the commissions of economy and agriculture; health and environment; educations; internal affairs, social affairs and labor; women; culture; youth and sports; as well as local administrations.

There are also offices of defense; religious affairs; technical consultations; media; oil and natural resources; development and planning; as well as humanitarian affairs.

The AANES operates a single directorate that of foreign relations.

The Justice Council consists of 13 members and was established on 25 April 2019.

A tax law that does not reflect offered services

Since it held reins to power in said areas, the AANES has imposed taxes on 13 different categories of professions, including even low-income professions of craftsmen and tailors. The taxes, according to official statements, “aim to develop public services, boost the economy, and realize social justice.” The people, for their part, have been discontent and often complain about the financial burdens that weigh on them.

New tax law

While most of the residents of the northeastern region suffer from deteriorating economic and living conditions, the co-chair of the Finance Commission, Salwa al-Sayed, announced, in early April, that 92-article tax law will come into force on 1 June.

Al-Sayed said, that the law “is one of the highly sensitive and most accurate laws, as it has a direct impact on all members of society in two respects. The first is its contribution to achieving social justice. The second is that it constitutes one of the resources to improve the administration’s [AANES] funds dedicated to rehabilitating infrastructure, subsidizing basic commodities, and improving the financial allocations for workers in [sub-]adminstrations.”

Taxes were divided into direct taxes, including the individual income tax—from which the military, the internal security forces and the families of the dead, as well as those working in the agricultural sector, were exempted—, in addition to vehicle taxes and corporate profits taxes. As for the indirect taxes, they include the luxury tax and a fee or stamp tax.

Is the law functional?

Taxes are considered one of the state’s key financial resources to fund its public expenditures, and an effective means to set economic and social life in motion. However, stress must not be laid onto the essential role of taxes, as much as upon choosing an appropriate tax system. Making such an appropriate choice depends on the state’s knowledge of the society’s economic, social, and political conditions.

Taxes also help realize social justice, since they are supposedly imposed on high-income segments of a society to be distributed on the less fortunate, those with lower income.

Even though direct taxes are closer to achieve the goal of social justice, than indirect ones, direct taxes still hold the potential of adversely affecting justice, particularly in developing countries.

In developing countries, for instance, low-income groups, particularly employees and dayworkers, barely have any chance to escape paying taxes or even try to evade the system altogether. Escape is reserved for groups with higher income, such as businessmen and merchants.

The purchasing power of citizens across Syria, regardless of the authorities in charge, decreased with the decline in the value of the Syrian pound that hit several lows over the past two years before it stabilized after the exchange rate was unified.

There is a gap between salaries and wages and prices of basic commodities, that are undergoing unprecedented spikes.

In addition to the war-effected economic downturn, there have been the repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic. Preventative measures that authorities put in place to control the spread of the novel virus, including recurrent closure of internal crossings and markets, as well as lockdowns, have all affected citizens’ livelihoods, especially in the AANES-held regions.

According to a report by the Global Network Against Food Crises, addressing food insecurity worldwide, Syria tops the list of the ten most affected countries in 2020, for food insecurity levels have increased by about 20 million people since 2019.

By November 2020, 12.4 million Syrians were food insecure, of whom 11.1 million were moderately food insecure, and 1.3 million were severely food insecure, according to the report.

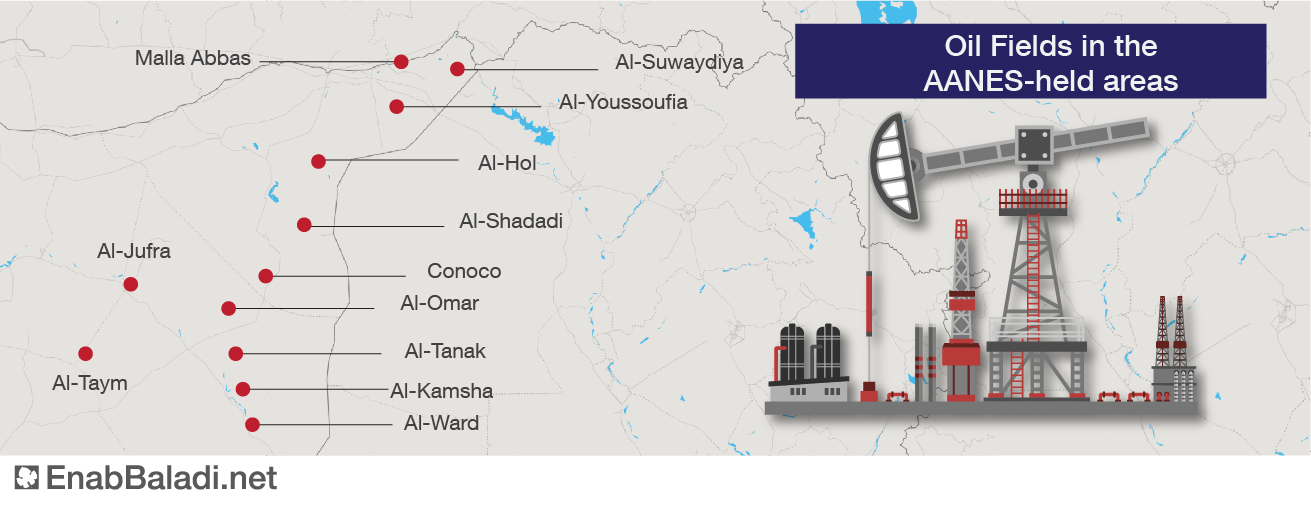

Al-Jazira oil, to whom is sold?

The SDF has been controlling oil resources in northeastern Syria for the past nine years, selling oil products to three major clients—the Iraqi Kurdistan, the Syrian regime, and the opposition.

In addition to small-scale smuggling operations into northern Iraq and the consumption on the local market, the SDF oil is sold to the Syrian regime through the Qaterji International Company and to the opposition through the al-Rawda and al-Hazwani companies.

There is little to no information as to the volume of production or the damage that befell oil fields since the SDF took over the region.

In a September 2019 report, the Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR) said that the SDF “produce[s] approximately 14,000 barrels of oil per day.”

According to the testimonies obtained by the SNHR, “the SDF currently sells a barrel of crude oil to the Syrian regime for around US $ 30, making a total daily return estimated at $ 420,000, a monthly return estimated at US $ 12.6 million, and an annual return estimated at 378 million dollars; this sum does not include the gas revenues.”

“The deliberate lack of transparency and the high level of secrecy imposed by the Autonomous Administration make current estimations uncertain. Similarly, there is no or little public information on how the oil revenue is spent,” researcher Hatahet stressed in his researcher on northeastern Syria economy.

“The Autonomous Administration has also made no effort to disclose its list of clients. This might be partly because of the US and EU sanctions on the Syrian public oil sector,” he added.

On 30 July 2020, Commander-in-Chief of the SDF, Mazloum Abdi, signed an agreement with a US oil company to modernize the oil wells it controls in northeastern Syria. It is worth mentioning that the US is a key partner and source of support to the SDF.

Trade is AANES’s lifeline

The AANES relies on foreign trade with Iraq and the domestic exchange of goods with the regime- and the opposition-held areas through several official and unofficial crossings. Such exchanges are the AANES’s major economic resource.

Two border crossings link the AANS-held areas with Iraq. These are Semalka, on the northeastern border of Syria, and the al-Yarubiya, north of al-Yarubiya town.

In January 2020, the United Nations (UN), based on a Russian proposal, deauthorized al-Yarubiya crossing with Iraq and al-Ramtha with Jordan, as routes for cross-border aid delivery without permission from the Syrian regime. Ultimately, only two crossings remained operative, the Bab al-Hawa and Bab al-Salameh with Turkey.

The AANES-held areas are linked with the Syrian regime-controlled areas through several crossings, including smuggling crossings run by smugglers and militias, especially in Deir ez-Zor, such as the Shuhail crossing on the Euphrates River. There are also official crossings, including al-Taihah in Manbij, the Tabqa near the city of Tabqa, and al-Akirshi in the southeastern countryside of Raqqa.

Since 20 March, the Syrian regime has unilaterally closed the crossings to those wishing to enter or leave its areas towards the AANES’s areas, as well as cargo and commercial transport, except for students, employees, and people seeking treatment.

In a 23 April policy forum held by the Washington Institute, expert Sasha Ghosh-Siminoff said that “the economic situation in SDF territory varies. Some areas were liberated much earlier than others, creating a gradient of recovery.”

He added that “the war has greatly diminished traditional connections between local economic hubs. Cross-river trade used to thrive in Deir al-Zour but now is minimal.”

“Such activity has instead been redirected toward the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI), forcing the SDF to grapple with new economic mechanisms while dealing with security issues at the same time.”

Siminoff called Cross-border trade “a key lifeline.” He added that “the KRI has significant social, cultural, political, and economic connections to northeast Syria—for better or worse, the two areas will always be linked. Cross-border aid is substantial, but the KRI’s semi-autonomous status is not the best setup for such assistance from a legal standpoint. If the Iraqi federal government wants to get involved, it will need to get al-Yarubiya crossing reopened.”

He concluded that “northeast Syria has enough natural resources to sustain itself, at some point, it will need a tax base, which it cannot cultivate without local buy-in. That is the route authorities should take, including more concrete import/export duties. Cross-border aid must be expanded as well; relying entirely on the Peshkhabur crossing is insufficient.”

What about domestic trade?

Local traders, who maintain relations with influential Democratic Union Party (PYD) officials, benefit from commercial exchanges with the regime, opposition-held areas and the KRG. Researcher Hatahet describes these traders as key players in the new economic structure.

Hatahet laid out this structure, saying “The Autonomous Administration’s expenditure includes the military, early recovery projects, the restoration of infrastructure such as irrigation channels and roads and the maintenance of the electricity grid and the cost of running public health, education and local administration institutions.”

“However, there are great strains on the viability of the AANES economic experience. Its economic, trade and planning organizations have faced challenges in implementing their ideals and are often perceived as a rigid bureaucracy, lacking structure and transparency and infested with nepotism and favouritism,” he added.

In addition, Hatahet argues that “the AANES still lacks control over large sectors of the economy and is vulnerable to constant probes by the regime and old elite members, and … is mostly dependent on Syrian state banks to provide liquidity in the market. The Syrian Central Bank is still operating in the area and is the primary source of SYP in the market.”

The SDC Co-Chair, Riad Dirar, told Enab Baladi on 29 April that “the wealth in eastern and northeastern Syria suffers the same embargo the rest of Syria is enduring,” indicating that economy projects are carried out within the frame of a “war economy”

He added that this mode of economic management is not a prelude to economic stability, but rather it is an administration of the economy that aims at survival.

Dirar dismissed accusations of “administrative failure” as “ignorance of facts” because it is not easy to manage the life of the region’s population, amounting to over four million.

He added that people in the areas east of the Euphrates River have a better life than others in surrounding areas, adding that all the mistakes committed were a result of constant pressures and conspiracies.

He said that “there is a shortage, and we need more stability, to achieve further progress and development.”

if you think the article contain wrong information or you have additional details Send Correction

النسخة العربية من المقال

-

Follow us :

Edited by Enab Baladi

Edited by Enab Baladi

A

A

A

A

A

A

More In-Depth

More In-Depth