Sakina Muhdi| Hussam al-Mahmoud | Nour al-Din Ramadan

On 6 April 2021, Idlib-based activists circulated a video of a teacher beating children while in line at the schoolyard. The video, a sneaked evidence of teacher violence, sent shockwaves through the Syrian community. Angry commentators, among them many parents, posed several questions as to the teaching methods that teachers are adopting in schools in northwestern Syria.

The phenomenon of using corporeal punishment by school teachers to discipline students into the realm of obedience and maintain their authority over the classroom is not new to Syrians. There is hardly a Syrian who was not beaten at a tender age by a teacher or principal, especially in government-run schools. The video, which triggered memories of a collective childhood experience, an unhappy one certainly, made viewers wonder why such physical discipline practices persist, and most prominently, what urges teachers to use violence under the guise of education.

There has been a divide in the attempts to answer these questions. Some commentators attributed teacher-violence to domestic discipline practices; others located the trend in the Baath Party mindset that used an iron fist for 50 years to reserve hegemony over the country’s institutions, including education, with relevant authorities making systemic punishment an integral part of established teaching policies.

In this extensive article, Enab Baladi discusses violence at schools in northwestern Syria, the challenges to education and teachers’ living conditions, and the effects of all these factors combined on students.

Student performance intensive?

“The teacher used physical discipline to force my kids to perform better at school. They actually showed improvement. We did not approve beating them at first but seeing that it was effective the teacher had our support. We were proud of their excellence. However, we were soon stricken with guilt that it was fear what made our children do better at school,” said Abdulilah al-Shamali, a father to three students at the Idlib-based al-Shaikh Youssef Elementary School.

The father told Enab Baladi that “my children had average scores, but I was not very satisfied with their status. At a certain point, they started to slip to under-performance. The school called and the teacher explained how poor they were doing in class. I urged her to reprimand them. She in return used physical violence to press them into doing better. I did not consent to beating them first, but when beating worked, I did not question her method.”

Not knowing the extent of disciplinary violence practiced against his children, Abdulilah did not mind the measure first, neither filed a case against the school—perhaps he was not aware that he was entitled to press charges against the school.

150 students in a worn-out tent made into a classroom in a camp east of Kafr Arrouq village, north of Idlib— 12 March 2020 (Enab Baladi)

School’s corporal punishment and local laws

In the governorates of Idlib and Aleppo, Administrative Order No. 961— issued by the joint Administrative Committee of education directorates in both governorates— proposes a set of regulations that govern education and school codes, safeguarding the child’s rights and obliging schools and other education entities, as well as teachers, to the order’s provisions.

Head of the Idlib Elementary Education Directorate, Mahmoud al-Basha told Enab Baladi that directorates adopt graduated punitive measures against students who violate the code of conduct. Students’ attention is first called to any offensive behavior; they are then given a formal warning; when needed, their parents are summoned to school. Teachers are prohibited from practicing corporal punishment against students, no matter how provocative their behavior might be. Teachers, instead, can send the students to the office of the principal or the psychological counselor to take the necessary action against them.

He added that the child safeguarding policies— set forth by the committee through the administrative order— were designed by the Idlib Directorate of Education with education-focused partner organizations. The policy defines several levels of risk and the type of punishment to be inflicted on a teacher who breaches the said policy.

Al-Basha demonstrated the penalty stated by the policy for each level of risk or harm the teacher poses to children/students protected by the policies. For level-1-risks, teachers are provided with a verbal or written warning. For Level-2- risks, teachers are provided exclusively with a written warning. For Level-3-risks, teachers are subjected to disciplinary wage deduction. For Level-4-risks, involved teachers are transferred and dismissed. For level-5-risks, the teacher is brought before the court.

Immediate dismissal for collective punishment

In the video mentioned above, capturing a scene of collective punishment at al-Baraem Model School, the teacher is using a hose to hit students on hands and other body parts. Commenting on the horrifying sight, al-Basha said that the use of a stick or any tool that might harm students renders the involved teacher liable for a written warning. However, the use of extreme physical force or abusive language against children, in addition to collective punishment or violence, qualifies teachers for immediate dismissal.

The disciplinary practice undertaken by the teacher in al-Baraem school falls under level-4-risk, covering abuse, violence, excessive use of force, and collective punishment. The case rendered the teacher liable for the punitive dismissal not only for beating the students but also for subjecting them to public humiliation in the school’s courtyard.

On its Facebook page, the Media Office of Saraqib and its countryside reported that the Idlib Directorate of Education ordered the dismissal of the teacher for violating the Child Safeguarding Policies.

Enab Baladi sent the Ministry of Education of the Syrian Salvation Government (SSG)—administratively running Idlib and its countryside— a request for comment, asking about the laws it has set up to regulate teacher-student relations in the areas under its control. The SSG did not respond.

The Idlib Directorate of Education is the entity in charge of the education sector in Idlib, and it denies having any administrative affiliation with the SSG.

The directorate publishes an annual statement reiterating its administrative independence, Mustafa Haj Ali, directorate’s spokesperson, told Enab Baladi in a previous statement.

Civil society organizations

Duty to raise awareness

Within the context of civil society organizations’ (CSOs) work, al-Basha said that schools and other education facilities, as well as administrative entities, hold periodic meetings and regular workshops with CSOs to discuss cases such as the one recorded in the video and needed punitive measures.

He added that the area’s teachers are trained in psychological support and teaching methods to develop skills on how to deal with children in all circumstances, given the different backgrounds and age groups they come from, while schools make sure that psychological counselors keep teachers engaged in such training programs.

Ikram al-Mustafa, director of education projects at Bonyan organization in Idlib, told Enab Baladi that the organization carries out several awareness initiatives centered on teacher-student relations, which target all school staff, not only teachers.

Al-Mustafa said that Bonyan runs teacher-aimed training programs which qualify them to provide psychosocial support for children and designs courses that supplement teachers with skills to maintain order in the classroom and connect children with disabilities with their classmates.

She added that Bonyan also provides awareness sessions informing teachers of the Child Safeguarding Policies and how to adhere to their provisions, focusing on showing teachers how paramount it is to enforce such policies.

She said that since 2019, the organization has held 13 teacher training programs, acknowledging that these training programs are necessary for teachers, dealing with all age groups and various course materials.

Ikram also defined the scope and areas of training that Bonyan covers, adding that as a prelude to each training program, the organization introduces teachers to psychosocial support (PSS), psychological first aid, classroom management, and behavior modification.

150 students in a worn-out tent made into a classroom in a camp east of Kafr Arrouq village, north of Idlib— 12 March 2020 (Enab Baladi)

Roots of teacher-violence

Home, or Ba’ath mindset?

On a school day, at 7:30 a.m. sharp, students would take their place in the queue. In one breathe, parrot-like, they start saluting the flag and shouting al-Ba’ath slogans, with which the ruling party seeks to sip into the minds of children.

In schools that lack laboratories, care methods but are overcrowded with portraits of the two al-Assads—Hafez al-Assad and his son Bashar al-Assad—students are subjected to violence under many guises, such as discipline, maintaining order, committing students to keep up with course materials, homework, and other student duties.

However, now that 10 good years have passed since large swathes of the country broke loose of the party’s grasp, it is striking that violence in schools should persist, particularly as it is one of the regime’s governance mechanism, which Syrians also demanded be abolished as they rose in their revolution.

The administrative officer at Hama Educational Compound, northwestern Syria, Khaled al-Faris, told Enab Baladi that teacher violence could not be considered a phenomenon, as it is limited to few individual cases that were addressed immediately.

He added that society contributes to perpetuating corporeal punishment in schools, referring to a group of parents that provide teachers with all entitlements over students, including their bodies, as they greenlight teachers’ violence-based approaches to teaching and disciplining.

Al-Faris said that educational counselors from the education directors visit schools regularly to assess the educational process, including whether students are being subjected to corporal punishment.

He added that should use of corporeal punishment be confirmed, the involved teacher is referred to the Internal Control Committee under each directorate, which decides the legal measures to be taken against them. He emphasized that all forms of violence, including beating, are intolerable, adding that students should be brought up on ethical and civilized principles.

Conditions of education are also a trigger

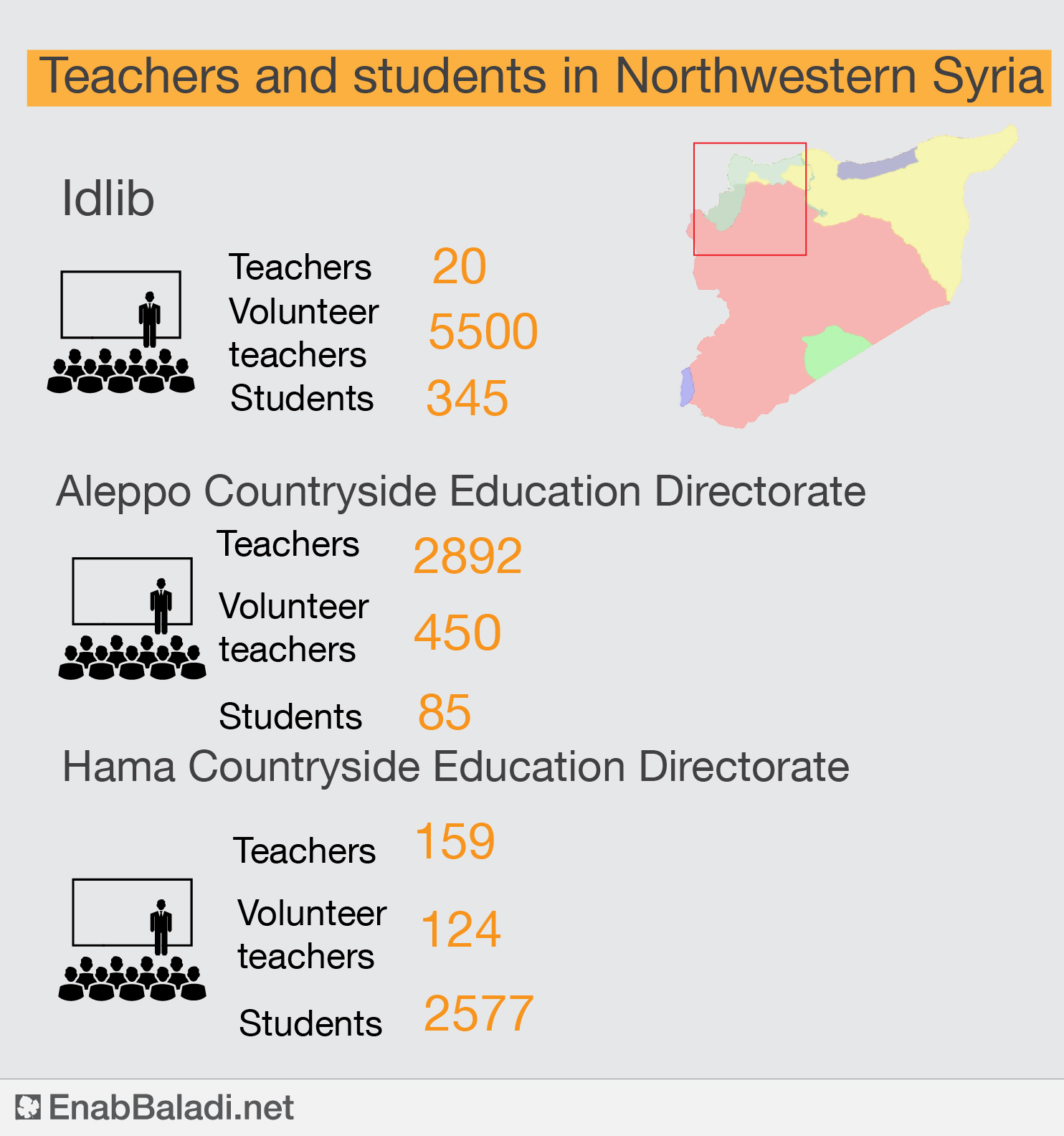

Al-Basha told Enab Baladi that funding that finances teachers’ salaries have been cut off in Idlib governorate since the beginning of 2020 because the European Union (EU) limited its support to first cycle education programs only. Before the curtails, the EU channeled donations through the Manahel organization to second-cycle programs and high schools.

Commenting on the relationship between the teachers’ financial status and use of violence at school, psychiatrist Wael al-Ras said that some teachers might resort to beating students affected by economic and social pressure, for such forces are sufficient to trigger violent reactions in adults in general, scholastic by teachers or domestic by fathers.

Al-Ras told Enab Baladi that teacher-violence could be attributed to several factors; one is cultural. There is this belief that corporal punishment is a solution to make students do better at school. Even though educational organizations and institutions have been designing courses against violence-based education, beating children remains a widespread phenomenon in various societies, including the Syrian society.

Al-Ras said that teachers have lost control and no longer have a mechanism to maintain order in the classroom, driving many of them to use violence to reestablish their authoritative voice. In addition to many societal factors, teachers might resort to beating because student provocation sometimes goes too far.

The poor financial and living conditions are naturally not limited to teachers. Children in northwestern Syria are also suffering due to harsh circumstances, including poverty, displacement, and lack of needs, barely answered by existing modest relief efforts, not to mention the shrinking support for education in northern Syria.

On the list of priority responses and humanitarian need reactions, education ranks after basic needs, such as camps, food, medical aid, and vaccines in light of the outbreak of the novel coronavirus (Covid-19).

Of the many other challenges that pose a threat to Syrian children’s rights to pursuing an education is that many are not enrolled in the school. Registration obstacles might put these children before adaptation difficulties, such as the inability to keep up with school material as they grow older. This will, in turn, disrupt their development and have a long-term impact on their future practical life, including having a career.

In a 2018 report, UNICEF said that nearly a third of children enrolled in school drop out before completing elementary education.

Because such dire conditions do not passe unnoticed, a UNESCO study found out that “13 percent of displaced children in Syria need specialized psychosocial support in the classroom.”

The study confirms that identifying and treating psychological trauma in children is a complex issue that requires specialization on the part of teachers.

According to the report, education in northwestern Syria is declining at a time when it is most needed because during “wars and armed conflicts,” education gives children space to express their fears and concerns and get rid of pent-up painful feelings, as well as develop new hopes for the future.

In a report issued by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) in January 2020, information compiled indicates that the UN did collect barely 18 percent of the funding required for the education sector, which needs an estimated nine million dollars.

In early 2020, the EU stopped support provided through Chemonics to the Idlib Education Directorate, which covered 65 percent of teachers’ salaries. The salary cuts promoted some teachers to seek other jobs to meet family needs and household expenditures. This, consequently, resulted in a growing shortage of teaching staff.

Funding deficits largely contributed to depriving children of their right to education. According to a study by the REACH initiative, about 50 percent of assessed target areas lack qualified teaching staff.

Home and moral realism

The psychiatrist Amer al-Ghadban, holder of a Ph.D. in educational psychology, said that corporeal violence against children in schools ties into similar forms of violence practiced against them at home. He added that if the family accepts beating as a manner of treatment between adults, the child too will accept it. This might affect the way children comprehend life and tend to normalize violence, particularly since children are bearing witness to authorities that are as hostile to citizens.

Psychiatrist al-Ghadban told Enab Baladi that the child’s frequent exposure to violence will prevent him from developing positive feelings, strengthening instead negative pathological emotions while forging enmities. These children might even develop a tendency to raise their children the same way in the future.

The effect of corporeal violence, beating, differs from one student to another, and whether the student has committed a punishable offense, particularly among younger children. The influence of beating is massive on children who did not do wrong and were treated unfairly. However, in case of an offense, even though the child might feel sad because the violence he/she is shown, they may feel that they deserved punishment. These approaches echo through moral realism, for according to the Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget, who argues that children tend to view rules as inflexible and unchanging to a certain degree.

According to moral realism, children consider negative punishment an automatic response to breaking the rules.

Al-Ghadban added that arising from associating teachers with these injustices; children start to develop a tolerance for injustice and abuse not from teachers only, but also from students because they assume that authority is oppressive and ultimately do not ask for help from the teacher of the administration in the unsafe space that school turns into.

He added that students must hold on to their rights when subjected to harm, stressing that reinforcing the role of the social counselor at school is of paramount importance, particularly in schools where violence against children is recurrent.

He stressed that beating does not help achieve effective learning outcomes or support the progress of a curriculum or an educational program.

For her part, psychologist Fatima Asaad told Enab Baladi that one of the reasons that helped establish the role of violence in society is normalizing violence in schools, which teachers often practice because they lack proper methods to handle situations and difficulties they might encounter while teaching.

According to a 2018 study by the University of Michigan, corporal punishment is found to lead to toxic stress in a child, which might “disrupt the development of brain architecture” in early childhood, with potential adverse impact on their cognitive and linguistic abilities, their mental health, as well as social and emotional development.

Violence warranted by Syrian Laws

The 1989 UN Convention on the Rights of the Child safeguards a child’s right to protection. Article 19 stipulates that “States Parties shall take all appropriate legislative, administrative, social and educational measures to protect the child from all forms of physical or mental violence, injury or abuse.”

Article 28 (2), focused on the children’s right to education, stresses that “States Parties shall take all appropriate measures to ensure that school discipline is administered in a manner consistent with the child’s human dignity and in conformity with the present Convention.”

Syrian lawyer Abdo Abdelghafour told Enab Baladi that, in 128 states worldwide, laws prohibit corporal punishment, while there is no specific article in the Syrian Penal Code that protects children from violence as belonging to one of society’s vulnerable groups.

Lawyer Abdelghafour referred to Article 185 of the Penal Code, which instead of providing a ban on violence against children, entitles parents and teachers to use corporeal violence on the pretext of “discipline,” and other guises permitted by “general custom.”

The Syrian law, exhaustive as its, does not provide a clear-cut definition of general custom, which instead is left open for interpretation, making children excessively vulnerable to corporal abuse and violence in school.

150 students in a worn-out tent made into a classroom in a camp east of Kafr Arrouq village, north of Idlib— 12 March 2020 (Enab Baladi)

The case against corporal punishment

Psychiatrist al-Ras said that the use of violence against children has direct behavioral and performative consequences, which affect the way children interact with their peers.

In addition to being extremely excitable, children might develop learning and comprehension difficulties or a tendency towards isolation; they might also use violence themselves against others or refuse to talk because they do not want to communicate with their surroundings.

There are also medium-term effects that get manifested through underperformance in school or the inability to build relationships. When children are exposed to violence at a tender age, their teenage years might also bear the mark of former abuses, turning into antisocial individuals.

Longer-term effects, however, are those which influence the way a child’s personality is formed, with some even developing personality disorders. In extreme cases of physical abuse, such as in the cases of sexual abuse, these disorders become difficult to treat and affect their professional performance. As a result, violence victims may develop a propensity to drug addiction or build personalities capable of self-harm and also of inflicting harm upon society.

UNESCO stresses that violence in education spaces is a daily reality that deprives millions of children and youth of their basic human right to education.

Citing estimates by Plan International, UNESCO pointed that 246 million children and adolescents are subjected to violence in and around schools every year.

The UN agency said that schools that do not provide children with safety violate the children’s right to education established by the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child and the Convention against Discrimination in Education, which aims to eliminate discrimination and encourages taking measures “against the different forms of discrimination in education and for the purpose of ensuring equality of opportunity and treatment in education.”

150 students in a worn-out tent made into a classroom in a camp east of Kafr Arrouq village, north of Idlib— 12 March 2020 (Enab Baladi)

How should parents respond to violence against children?

Psychiatrist al-Ras said that parents could do several things to mitigate the negative impact of a child’s experience with violence, including trying to boost the child’s self-esteem, speaking to the concerned school’s administration, and keeping the involved teacher away from the student.

To boost the child’s self-esteem, the psychiatrist said that parents must allow the child extra playtime with their favorite toys, encourage them to achieve, and try to get children engaged in activities involving other children, particularly because children themselves can still heal some of the psychological harm they have been subjected to.

Sociological interpretation of the violence practiced in schools in northern Syria

Talal Mustafa

Former professor of sociology at the University of Damascus and a researcher at the Hermon Center for Contemporary Studies

Violence is a major aspect of the suffering of Syrians in the northern parts of the country, especially in schools. The effects of violence have many forms and are obvious throughout the area’s cities and towns, individual or collective, directed towards the self or at others, reaching an extreme case in education institutions.

There is daily news of students and teachers involved in violent incidents— a familiar scene in schools. This proves that the aura and sacredness of the educational institution and staffers have fallen apart, while it also shows the extent of aggression that students can practice, particularly those who show difficulty in adapting to the school environment, manifested in disturbing behavioral and performative actions. This is turning the school into a source of violence, although the school is supposedly designed to be a space for reducing the negative effects of violence taking place in other social spaces.

This violence in schools leads to chaos, confusion, and emotional tension, resulting in impacts that involve both students and teachers. Teachers and students tend to underperform.

It is important that education institutions conduct research on violence in schools because the school is the second institution after the family and is equally responsible for an individual’s sound social upbringing. A segment of these research efforts must investigate teacher violence because teachers are close enough to students and can best identify their social problems. Such research work can be utilized in designing heuristic social and psychological counseling programs aimed at reducing the phenomenon of school violence and applying them in schools north of Syria.

To address the scientific reasons for the emergence of school violence in northern Syria, it is necessary to consider outcomes and findings of former scientific, social, psychological, and educational researcher-made on schools. There is an abundance of theories analyzing school violence, notably Functional Constructivism (FC) that associates violence to its social context, arguing that violence rises either as a result of an individual’s disconnection from social groups that organize and direct behavior or due to the loss of social norms and controls.

Sigmund Freud, founder of the psychoanalytic theory, attributes violence the ego’s inability to adapt the instinctive innate tendencies to the demands, values, ideals, and standards of society, or its failure to transcend these through substituting aggressive, primitive, and sensual tendencies with activities that are moral, spiritual, religious and socially acceptable. When substitution fails the individual’s instinctive desires, and tendencies are unleashed and seek satisfaction through violent and criminal behavior.

Other psychoanalytic theorists argue that violence results from the subjective feeling that an individual experiences when he encounters an obstacle that prevents him from achieving a desired goal or an aspiration. This state of frustration leads to anger, which in turn leads to aggression.

These multiple interpretations indicate that it is difficult to attribute violence to a single factor in schools in northern Syria, especially given the armed conflict and the absence of specialized institutions.

However, relevant education institutions can work along a few recommendations to limit the impact of violence:

- The design of heuristic educational, psychological and social counseling programs for students must be done with extreme care. Efforts also must be invested to raise awareness of the dangers and risks that violence in school poses. Social and psychological counseling specialists must handle this task with caution.

- Students must be encouraged to hold student-led social, sports, and cultural activities and competitions, as to have productive channels of use to students themselves and the school.

- Values of collegiality, brotherhood, and friendship must be nurtured among students, in addition to instilling a sense of social and national responsibility in each student.

if you think the article contain wrong information or you have additional details Send Correction

النسخة العربية من المقال

-

Follow us :

Edited by Enab Baladi

Edited by Enab Baladi

A

A

A

A

A

A

More In-Depth

More In-Depth