Saleh Malas| Diana Rahima| Jana al-Issa

Soon the streets of regime-held areas will drown in manifestations of loyalty, from banners to portraits, with inscriptions calling for “renewing allegiance, forever!”

The Syrian People’s Council set the date for presidential elections as on 10 May outside Syria and 26 May inside. Accordingly, Bashar al-Assad, head of the Syrian regime, notified the Supreme Constitutional Court that he will run for reelection— for the third time.

As al-Assad joins the race, the Syrian regime would be abandoning all its obligations under the United Nations (UN) resolutions which tie elections to an overall political transition, “agreeable to all Syrians.”

On the other end of this paramount political event, the Syrian opposition and many international actors in the Syrian issue continue to deny the legitimacy of elections because they are heedless of standards that guarantee independence and impartiality under UN supervision, for elections and the circumstances they are held under threaten to prolong the conflict in Syria, incorporating the political, military and economic tools already deepening Syrians’ woes.

In this extensive article, Enab Baladi discusses the elections’ legitimacy within local and international legal contexts and their political impact on Syria’s future.

Legal screening

In a 2019 November interview, al-Assad told Russia Today’s host that “any Syrian can be the president. There are many Syrians qualified for this position. The country cannot be tied to one person only and permanently.”

However, presidential candidates cannot drift away from the route marking the authorities’ aims, censored politically and by security services, as well as by the legislative frameworks of the constitution and laws of the presidential elections. Nominees must pass the legal screening test that serves the policy of the Syrian regime.

A Syrian woman casting her vote for the People’s Council elections at a polling station in the capital Damascus– 19 June 2020 (AFP)

For legal reference, the Syrian regime is basing elections on the 2012 Constitution, which the opposition considers “illegitimate,” given the ill-suited conditions under which the constitution was approved, particularly the referendum procedures, the way it was put into effect, and the fact that it is was custom-made to accommodate the existing regime’s needs.

Title I of the Constitution, under Article 3 of the overreaching principles, imposes eligibility requirements on persons serving as the republic’s president, denying non-Muslims and holders of second citizenship access to nomination. The title also defines the term of service, saying that the elected president shall serve a seven-year term and can be elected for only one more successive term.

Article 84 of the 2012 Constitution also requires that candidates must: be at least 40 years old; be Syrian by birth, of parents who are Syrians by birth; enjoy civil and political rights and not convicted of a dishonorable felony, even if he was reinstated; not be married to a non-Syrian wife; have lived in Syria for 10 years continuously upon nomination.

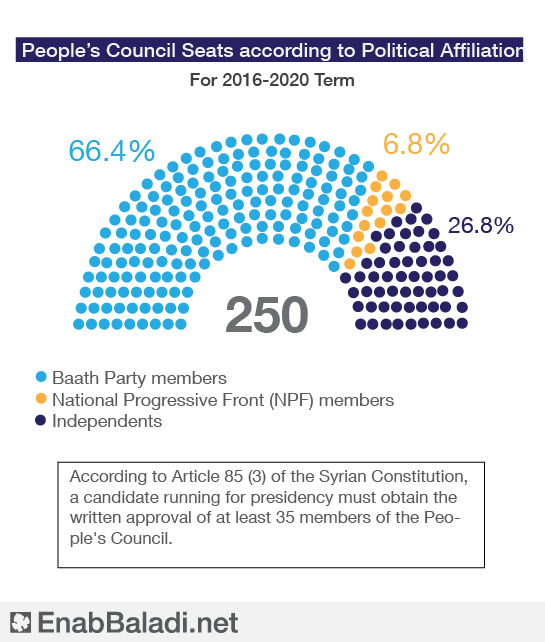

According to Article 85 (3), a candidate must be granted the written approval of at least 35 members of the People’s Council. This requirement denies all opposition figures the opportunity to run for the office, particularly given the hegemony of the Baath party over the council’s seats.

In an April 2020 research project report, researchers Ziad Awad and Agnès Favier detected a significant increase in council members affiliated with the Baath party.

The report demonstrates that the number of members politically affiliated with the Baath Party increased from 136 in 2007 to 166 during the 2016-2020 polls, dominating over 66.4% of parliamentary seats, leaving 17 seats, 6.8%, for the National Progressive Front Parties (NPF), and the remaining 67 for independent members, 26.8%.

A research paper conducted by researcher Mohsen al-Mustafa with Omran Center for Strategic Studies indicates that representation of the Baath party has increased steadily over the past legislative terms since the president of the Syrian regime, Bashar al-Assad, resumed the presidency in 2000, at the expense of independents and the NPF.

Article 8 (A) of the 2014 General Elections Law provides for the formation of the Damascus-based Supreme Judicial Committee for Elections. The committee is tasked with administrating Syrian elections and referendums, including full oversight of the parliamentary elections.

Article 8 (D) also stated that the committee shall exercise its duties and competencies in complete independence, impartiality and transparency, prohibiting any party from interfering in its affairs and tasks or limiting its powers.

However, the committee is not independent because the judicial authority in Syria is headed by the President of the Republic himself according to Article 65 of the Syrian Judicial Authority Law. The president also presides over the Supreme Judicial Council that appoints, promotes, and dismisses judges enabled by Article 133 of the Syrian constitution.

Furthermore, Article 34 of the General Elections Law gave the Supreme Constitutional Court jurisdiction to supervise the presidential elections, challenge them and announce their results, by examining the legal validity of applications for candidacy and deciding on them within the five days following the deadline of candidacy applications’ submission period. Simultaneously, in line with Article 141 of the Syrian Constitution, it is the president that names and appoints the court’s members through a legislative decree and it is before him that they take the oath.

Consequently, the court organizing the presidential elections lost its judicial independence by being directly subordinated to the President of the Republic through these constitutional and legal articles.

This means that it is impossible for a presidential candidate to obtain the approval of 35 members of the People’s Council and the Supreme Constitutional Court without the approval of the Syrian regime, which gives the regime control over the presidential elections and its results in conjunction with the absence of a neutral party to oversee this process.

Weightless candidates

The Syrian regime is using people who do not have a real political or social base to contest elections outside the purview of the UN Security Council’s Resolution No. 2254.

Hayed Hayed, Senior Advisor at Chatham House, told Enab Baladi that the candidates who have so far demanded their right to run for office, except for Bashar al-Assad, are “unknown and do not have any reliable public base to run for municipal or provincial elections.” Therefore, the results of the elections are “known even before the elections are even conducted.”

He added that these “puppets” are permitted to run for presidential elections only to ensure that al-Assad will win the elections, “however, under a more democratic appearance.”

This is not the first time that the government of the Syrian regime uses individuals who do not have public weight to run for the presidency. In the 2014 elections, two people ran for office, Hassan al-Nouri, a former Syrian minister, and Maher Hajjar, a member of the People’s Council during the 2012 term.

Enab Baladi tried to track the political standing of Hassan al-Nuri and Maher Hajjar after the elections in 2014 but found out that neither had any political or public activity. Enab Baladi could not even obtain general information as to what both figures are doing today.

In an article titled “Syrian President Easily Wins Referendum,” Washington Post covered the results of the 2007 presidential elections. “President Bashar Assad won another seven years in office, getting 97 percent of the vote in a referendum on his leadership in which he was the only candidate.”

The newspaper also captured the divide between loyalists’ reactions to the results, who “in white caps and T-shirts bearing Assad’s picture beat drums and danced in the streets of Damascus to celebrate the result” and the opposition’s.

Featuring voices of protest, the newspaper quoted Maamoun Homsi, a Syrian dissident living in Lebanon, who “dismissed the election results as a ‘forgery,’” and called them a “blatant aggression on the minds, dignity and reputation of the Syrian people.”

The regime and its allies are still working to change the position of some Arab and European countries towards what is happening in Syria, and the elections are part of these efforts. Hayed said that this time too, the regime is trying to present the presidential elections in a “democratic” manner by allowing other people to run for office.

He added that even though the “game is obvious” to all observers of the Syrian situation, the regime is reusing the same tools to prove that the elections are “democratic.” This democracy-based “propaganda” will also be used by Arab and Western countries that are striving to normalize relations with the government of the Syrian regime.

A poster of the head of the Syrian regime, Bashar al-Assad, saying “With You” outside a store in the Syrian capital Damascus – 16 April 2021 (Rami Al-Bustan)

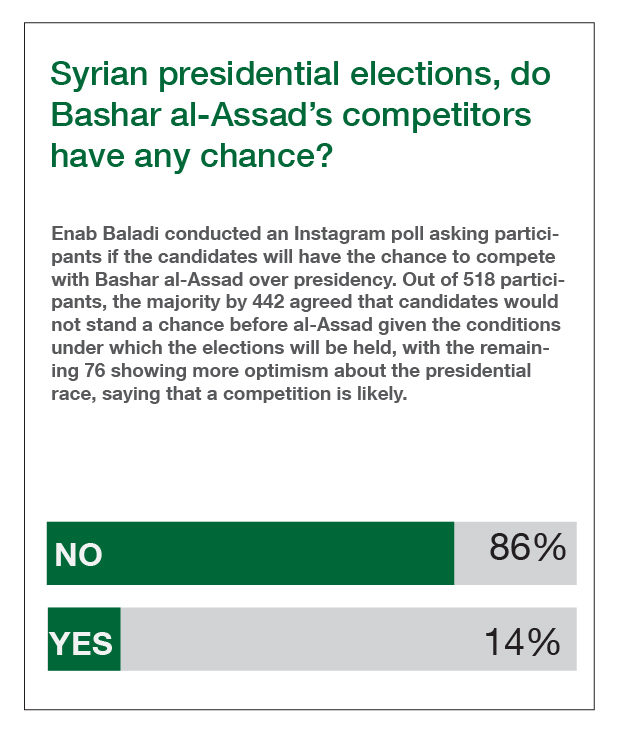

Opinion poll

Enab Baladi conducted an Instagram poll asking participants if the candidates will have the chance to compete with Bashar al-Assad over the presidency. Out of 518 participants, the majority by 442 agreed that candidates would not stand a chance before al-Assad given the conditions under which the elections will be held, with the remaining 76 showing more optimism about the presidential race, saying that competition is likely.

Resolution 2254 left behind

Election results that will not be recognized internationally

The UN, actors in the Syrian affair and the Syrian opposition consider Resolution No. 2254, issued by the Security Council in December 2015, the main reference for reaching a political solution in Syria.

Article 4 of the resolution expressed support for “a Syrian-led political process that is facilitated by the United Nations and, within a target of six months, establishes credible, inclusive and non-sectarian governance and sets a schedule and process for drafting a new constitution, and further expresses its support for free and fair elections, pursuant to the new constitution, to be held within 18 months.”

In early 2021, the US and the European Union (EU) declared that they will not recognize the presidential elections in Syria and have pledged to hold the regime accountable for committing human rights violations.

In a March interview, the EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy and the Vice-President of the Commission, Josep Borrell told Enab Baladi that “if we want elections that contribute to the settlement of the conflict, they must be held in accordance with UN Security Council resolution 2254, under supervision of the UN, and seek to satisfy the highest international standards.”

He added “they must be free and fair, all candidates must be allowed to run and campaign freely, there is a need for transparency and accountability and, last but not least, all Syrians, including members of the diaspora, must be able to participate. The regime’s elections later this year cannot fulfill these criteria, therefore they cannot lead to international normalization with Damascus.”

Last March, Associated Press said that the US cautioned the Syrian President Bashar al-Assad that the Biden administration “will not recognize the result of its upcoming presidential election unless the voting is free, fair, supervised by the United Nation and represents all of Syrian society.”

Turkey also refuses to recognize the Syrian presidential elections and considers them “lacking legitimacy,” because holding any elections in Syria must necessarily be accompanied by a political solution to acquire the status of legitimacy.

On April 20, Turkish Foreign Minister, Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu said that “the elections organized by the regime alone in Syria are illegitimate, and no one recognizes them.”

He stressed that Ankara will not recognize these elections, because “supporting illegal elections is inconsistent with our principles.”

The Turkish minister added that the Syrian regime should acknowledge that a military solution in the country is unlikely, which makes it imperative that the regime focus on the political track and give it importance, considering at the same time that the regime does not want a political solution.

The UN also announced that it is not involved in the presidential elections to be held in Syria, stressing the importance of reaching a political solution in accordance with Security Council Resolution 2254.

During a 21 April press conference, spokesman for the Secretary-General of the United Nations, Stéphane Dujarric, said that the presidential elections in Syria “are not part of the political process established under resolution 2254.”

He added that “the election is being held under the auspices of the current Constitution. They’re not part of the political process. We are not involved in the election. We have no mandate to be.”

“Negotiations meant for display”

The impact of unrecognized elections

Researcher at Omran Center for Studies, Maan Talaa told Enab Baladi that several countries and international organizations’ condemnation of the elections in Syria is unlikely to accelerate the political transition process for several reasons, which are related to the essence of the political process. At the heart of this process lies the logic of crisis management which so far has been closer to “negotiations meant for display”. The outcomes of condemnation, negotiations, are not clear yet. Therefore, the political process itself is suffering from disruptive factors.

He added that the Syrian regime’s, past, present, and probably future, abstinence from engaging in the political process can be viewed as the regime’s attempt “to accept things just for the sake of appearances, and then working to dilute and evade them,” particularly because the political activities the regime is engaged in are not carried out under Resolution 2254.

Researcher Talaa added that because the Syrian regime is attached to the presidential entitlement itself, the regime cannot exist without elections, which it uses to strengthen negotiation papers in expressing its political interests and dealing with the international community. Accordingly, the elections will not spur the political process, but will rather pose more difficulties, particularly since the elections are being held within “the freeze scenario formula, or as geographic centralization” as they will be conducted in the areas controlled by the Syrian regime, leaving out the areas held by the Autonomous Administration and the opposition in northeastern and western Syria.

Normalization has to do with actors’ map of interests

Researcher Talaa said that normalization with the regime is not related to the fact that elections are held or not, but rather to changing the map of interests of international powers and active forces, including Washington and Moscow.

Both are dealing with the regime using the sanctions-approach which is influencing the regime’s legitimacy. The US seeks to delegitimize, while Russia aims to support and legitimize the regime internationally. The elections are a new element to break this formula equipping one of the two parties with a new tool to deal with the Syrian file.

He added that all the political parties, involved in the Syrian issue, are aware of the illegality of the presidential elections in Syria on the local and international levels, but Moscow will promote for al-Assad’s legitimacy to talk about files related to reconstruction and the return of refugees. This, the researcher said, will lead to reactions from many countries by imposing more sanctions that will hamper a reconstruction dialogue with the regime, making the post-war challenges existential for the Syrian regime.

Researcher Talaa said that elections that are currently taking place in Syria are akin to a “formal decor,” given the status of the political landscape. He added that the elections will have little to no influence on the political process within the context of normalization with the regime because this political detail is linked to beyond-Syria contexts, namely the said map of actors’ influence and intersecting interests.

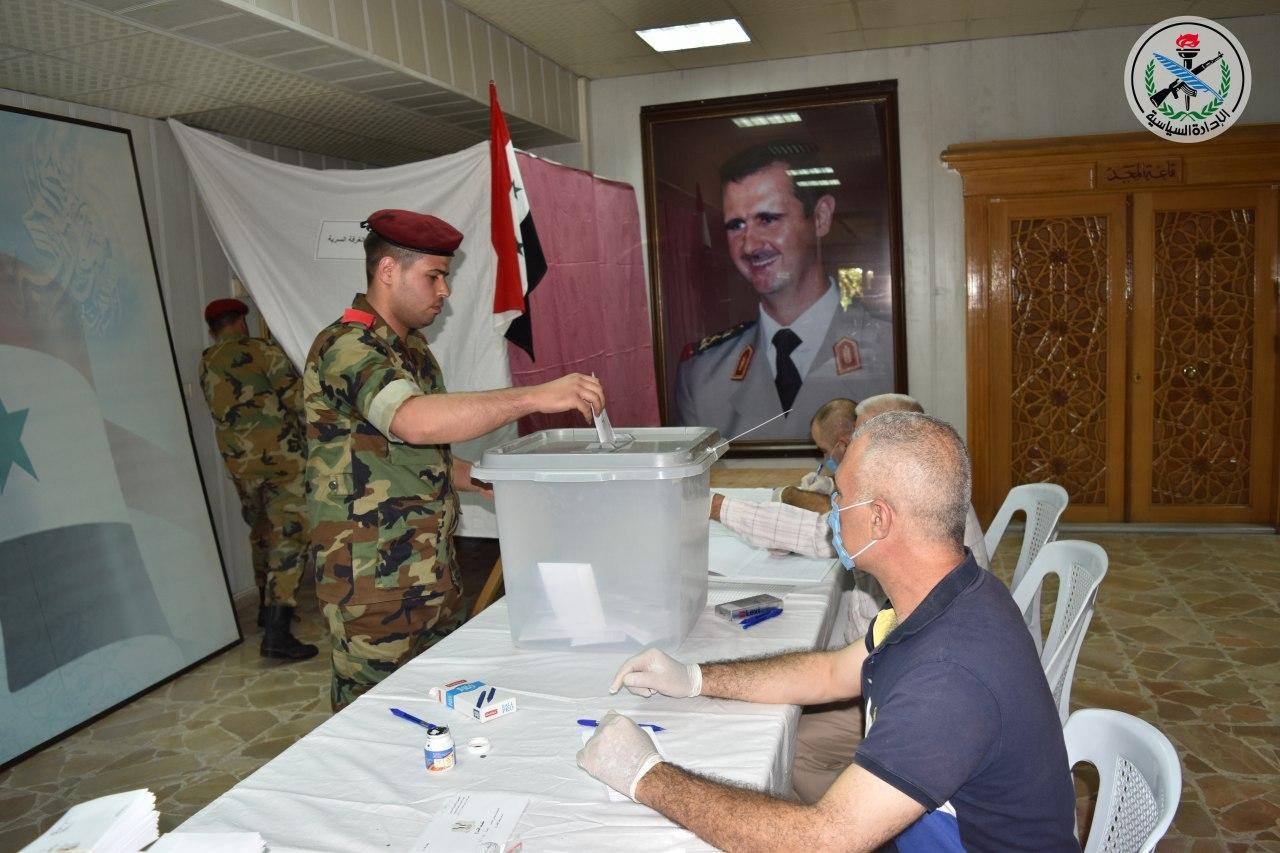

A Syrian soldier casting his vote at a polling station during the People’s Council elections, with a picture of the president of the Syrian regime, Bashar Al-Assad, appearing in the background – 19 July 2020 (SANA)

Elections are at odds with negotiation process

Where is the Constitutional Committee?

Politically, the presidential elections in Syria are grounded in a continuous disregard for negotiations with the opposition since the Syrian Constitutional Committee was first established in 2019, with the main goal of drafting a new constitution that would pave the path for a political transition in Syria.

The attempts of the Constitutional Committee have so far failed to achieve any progress on the political level, for the core issue of its meetings—held by the three delegations of the opposition, the regime and civil society— was to draft a new constitution, form a transitional governing body, and end with elections under the supervision of the UN— that meet “the highest international standards” which ensure transparency and accountability, and allow all Syrians, including refugees, to participate.

The co-president of the opposition’s side of the Constitutional Committee, Hadi Al-Bahra, told Enab Baladi, that the upcoming elections are “illegitimate” and are clear evidence that the Syrian regime is not interested in solving the crises of the Syrians, nor in implementing Security Council resolutions.

He added “Syrians witnessed what happened in the previous illegal elections of 2014. And everyone knows what the living and economic conditions in Syria were then, and how they are today.”

He added that, with holding the presidential elections, the regime insists on repeating the same “disastrous measures that made Syria on top of the poorest countries.”

Al-Bahra said that these elections will complicate the situation in Syria and will only be recognized and supported by countries that support the Syrian regime.

He also established a direct link between the legitimacy of the elections with the release of detainees and providing information about the fate of those forcibly disappeared in Syria.

Conditions to set negotiations going

The work of the Constitutional Committee is seen as a base for establishing a new political structure in Syria, should it be able to fulfill its mission defined by the list of procedures that Security Council-designated parties agreed upon.

Researcher at Jusoor for Studies, Wael Alwan, told Enab Baladi that the Syrian regime should provide concessions so that the Constitutional Committee can achieve its mission.

He added that two conditions must be met for the Constitutional Committee to be effective. The first is that Moscow predominates sovereignty decisions in Syria at the expense of Tehran.

The second condition is that the international community, led by Washington, should present Moscow with some negotiation wins in exchange for Russian concessions in the form of constitutional products, knowing that wins that Russia wants are not exclusively Syria-related.

There will be no prospects for the future of the Constitutional Committee unless Washington and Moscow reach an agreement.

In a briefing to the Security Council on 9 February, the UN Special Envoy for Syria UN envoy, Geir O. Pedersen, described the fifth session of the committee as a “missed and disappointing opportunity,” noting that there was not “a work plan for the future as of yet.”

He stressed that the committee worked the way it did in former rounds and that the approach was not viable, no progress could be achieved without changing the way the committee is working.

Poster-size photograph of the head of the Syrian regime Bashar al-Assad, with an inscription expressing support for his decision to run for the Syrian presidential elections—2014 (AFP)

“Blueprint” to construct a state

Designing elections in post-conflict Syria

Post-conflict elections are a “blueprint” to guide countries through the transition from a state of war to a state of peace, as it is the basis for any democratic political experience.

Enab Baladi obtained a copy of a research paper by the International Research & Exchanges Board (IREX) on elections and media in the post-war phase, which stressed that the main challenge in deciding on the timing and sequencing of post-conflict elections, “is how quickly, and when is it best to hold [them].”

The paper added that “elections provide an exit strategy and are a means to an end. Such elections may be imperfect and messy,” but still are the only way to resolve ongoing conflicts.

Independent election commission

The paper added that “in some countries, elections are managed by an independent authority known as an independent election commission. In other countries, elections are managed by the Ministry of the Interior. Some countries have a mix of both. Whatever the case, the body managing the elections must ensure that several things are in place before an election can take place, guided by international standards and best practices.”

The paper also highlighted the role of the media during the electoral process, saying that “elections involve several phases, and it is important to know what happens in each phase and what the media’s role can be in each of these phases.”

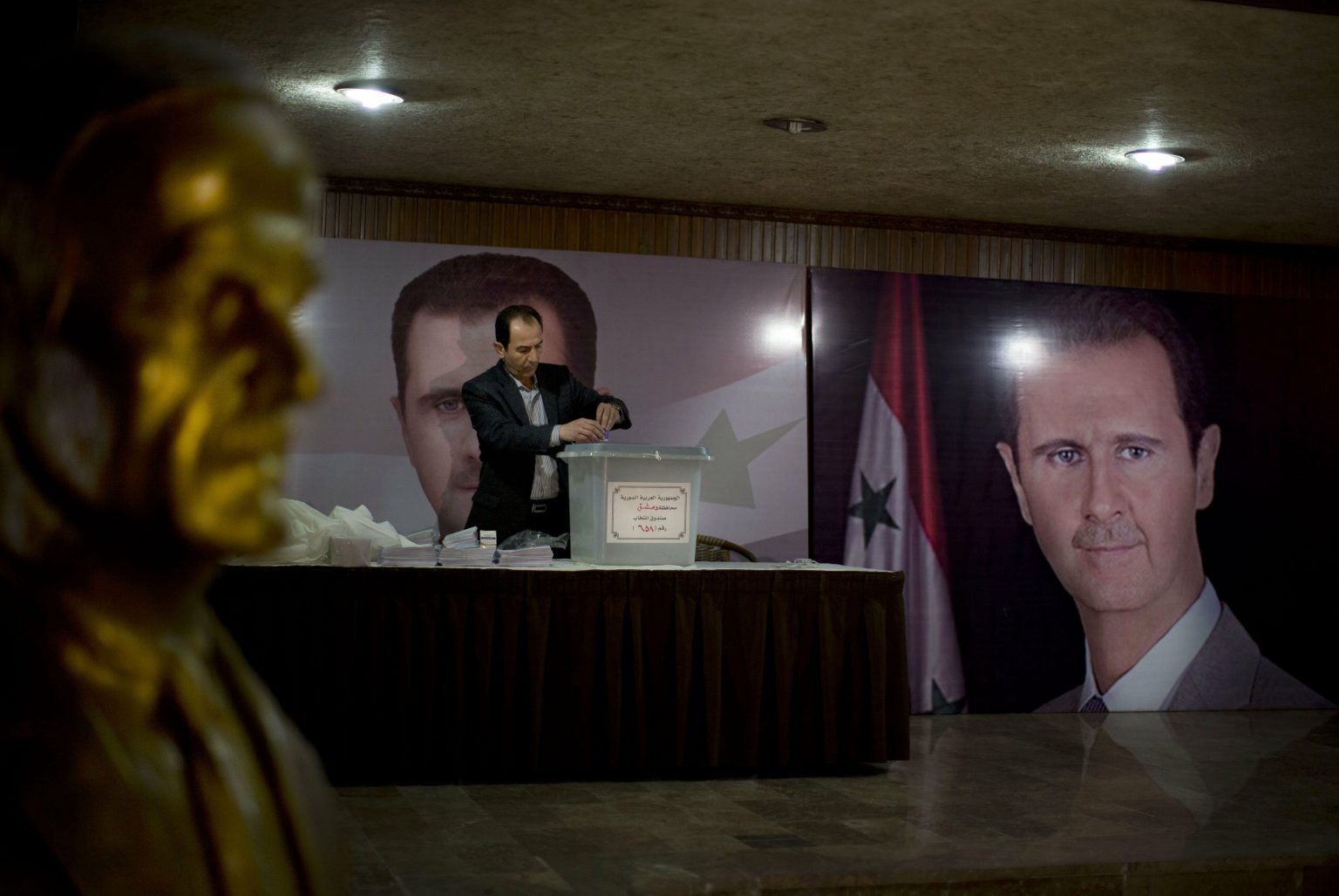

A Syrian poll worker waiting for voters at a polling station for the People’s Council elections, where posters of the head of the Syrian regime, Bashar al-Assad, are displayed, along with a statue of al-Assad the father – April 2016 (AP)

Observation role by the media

According to the IREX-issued researcher paper, “the media acts as a watchdog by scrutinizing the electoral process itself, including the management of the election, in order to evaluate the fairness of the process, its efficiency, and its probity. Reporters therefore need to be well aware of the election rules, how the election authority operates and how the voting is conducted.”

The paper adds that “election needs a legal framework, which means that there needs to be an electoral law and an electoral system,” and it is part of the media’s role to monitor whether constitutional provisions and existing laws are enforced, through investigating into the fairness of representation design and poll stations’ distribution, as to include all social components, among them minorities.

The media also should “examine whether the body organizing the election is fully equipped to do its job by checking how election officials were recruited, and . . . how election materials were procured? Was there a transparent bidding process?”

Within the observation mechanisms, the paper says “Some countries invite international observers to observe their elections and allow domestic observers to observe their own elections. Before they can do so, they need to be accredited. Observers observe and report on what they have seen. They have no right to interfere in an election or tell officials what to do.”

If invited, “[observers] too should be allowed to observe the count. After the counting has ended,” given that certain countries do counting at polling stations, while others transport the “the ballot boxes … to counting centers where they are counted.”

In conflict-stricken countries, the paper says that “special provisions are usually made for the internally displaced to vote. Also, provisions are made for Out of County voting, to enable refugees to vote.”

Civil engagement

The research paper defines civic participation as “becoming involved in civic affairs. It means getting informed about the issues facing the community and getting involved in making life better for ourselves and our community. It means participating in civic life and assuming the roles, rights and responsibilities associated with such participation.”

Stressing the importance of civic participation, the paper demonstrates that “it is important to be an active citizen, to be civically engaged, in order to change things,” because refusing to participate “means that people will never be able to change things, and they simply let things go on as they are and rely on others. Civic engagement helps make people aware of the needs of their community and how its problems can be solved, in order to bring about change.”

if you think the article contain wrong information or you have additional details Send Correction

النسخة العربية من المقال

-

Follow us :

Most viewed

- Printing Syrian currency in Europe... A file on the table

- Books make a comeback in Damascus libraries after being banned under Assad

- Complex steps to establish new Syrian army

- National Security Council in Syria: A necessity imposed by reality

- SDF-Damascus agreement in Aleppo: A test balloon for broader consensus

Edited by Enab Baladi

Edited by Enab Baladi

A

A

A

A

A

A

More In-Depth

More In-Depth