Enab Baladi- Zeinab Masri

Ibrahim, a merchant from Idlib, paid 2000 USD to get the Turkey-issued Merchant Card, which permits him to pass in and out of Turkey without having to suffer routine restrictions. To his surprise, the Turkish authorities at the Bab al-Salameh border crossing prevented him from carrying in a bag filled with “gifts” as he headed to Turkey.

In the bag, Ibrahim, who requested that his last name be withheld for security reasons, had clothes and several perfume bottles. These he purchased as gifts for his family members, who live in Turkey. The bag’s contents were not meant for trade purposes; but still, the Turkish border employee told him to get rid of it, he told Enab Baladi.

Ibrahim spent some time talking the matter with the employee. He finally succeeded in convincing him that his bag’s load was gifts, not merchandise.

Having gone through this, Ibrahim could not but wonder, why would Turkish authorities deny Syrian merchants the right to transport authorized goods and commodities, for civilian use or commercial purposes, across borders?

The situation that the Syrian merchant was subjected to on the Turkish divide of the border strip gave rise to several other questions that beg to be answered, particularly ones relating to the mechanisms regulating commercial exchanges and the economic dynamics governing cross-border relations between Turkey and areas throughout northern Syria.

In this extensive article, Enab Baladi brings to focus Turkey’s economic contributions into the areas in northern Syria, discussing also the profits both sides are making.

What import/export mechanism is adopted?

Merchant cards govern Turkey-northern Syria’s commercial exchanges

“Transporting goods from areas in northern Syria to Turkey is extremely difficult and limited. Merchants mostly bring in goods from Turkey, not the other way around,” merchant Ibrahim told Enab Baladi. “The Merchant Card was even founded to facilitate goods’ access from Turkey to northern Syria.”

To Turkish territories, Ibrahim said that Syrian merchants can only ship goods such as clothes, tea, or cigarettes, which are cheaper in northern Syria than those sold in the Turkish market. At some point, merchants were also allowed to transport cell phones, but these were banned later.

Ibrahim paid 2,150 USD to obtain a “commercial permit”—2000 was paid to Turkish relevant departments, and 150 were the fee for the commercial register issued by the Azaz City Chamber of Commerce, in northwestern Aleppo city. In addition to this initial sum, Ibrahim will have to pay an annual 1,500 USD to renew the permit.

The Turkish National Post and Telegraph Directorate (PTT) branch in Azaz city, Aleppo’s countryside- 25 February 2021 (Enab Baladi)

“Commercial permit”

The process of getting a “commercial permit” or the “merchant card” is overseen by the chambers of commerce operating across northern Syria.

The “merchant card” is the name people use to refer to the “commercial permit.” The card/permit, liable to Turkish authorities’ approval to be granted, allows holders to enter Turkey, shop there, and then bring back the procured commodities to areas north of Syria.

Merchants must obtain a number of documents and meet a set of conditions to be granted the “commercial permit.”

Merchants should own a professional license issued by the local council; lead a commercial activity according to which they are granted the license; and get a commercial register after obtaining the license, Director of al-Bab City Chamber of Industry and Commerce, Zain al-Abideen Darwish, told Enab Baladi.

Once the said conditions are met, merchants apply for membership with the commerce chamber, because it is the membership that enables concerned local councils to apply for the permit/card from the Turkish authorities. Some merchants apply for a six-month-permit, which costs 1000 USD, or one-year-permit, which costs 2000 USD, Darwish added.

For its part, the commerce chamber provides the Turkish authorities with the necessary information and pays the fee. The Turkish authorities then issue the permit that allows Syrian merchants to practice trade across borders.

Free trade in northern Syria

Foreign trade between Turkey and northern Syria is going on unhampered. Commercial exchanges are permitted, so is transporting commodities from northern Syria, through Turkey, to Iraq or the Gulf region, al-Darwish told Enab Baldi, noting that merchants are prohibited from importing all “security-related” products or chemicals into the region.

Turkey imports specific goods when needed, he added. “Having a surplus, what would Turkey import from northern Syria?”

Applicants tend to believe that paying the 1000 USD fee is sufficient to get them the “commercial permit.” However, before granting any permits, Turkish authorities monitor merchants’ commercial activities within Turkey, whether importing goods from Turkey to Syria or the other way around. The permit is granted to merchants, not regular individuals. And it is definitely not granted for “tourism” in Turkey, al-Darwish added.

Northern Syria has been adopting the free trade policy, regulated by a set of trade terms, Minister of Economy of the Syrian Interim Government (SIG), Abdulhakim Masri, told Enab Baladi.

| Under a free trade policy, foreign goods and services can be bought and sold without restrictions. States adopting this policy do not prohibit their citizens from selling products made in other countries.

This trade pattern also adheres to principles of protectionism; namely, policies that seek to protect local industries from competing with international ones, by imposing particular tariffs or taxes on foreign goods, and also through defining the exact amounts of goods to be imported. |

Minister Al-Masri told Enab Baldi that there is not a trade agreement between the SIG and the Turkish government. Agreements were sealed between the Turkish government and Syrian merchants.

Except for a few types, all goods from Turkey are allowed access into northern Syria. Similarly, merchants are allowed to export all sorts of goods to Turkey, unless they are classified as having a “special status”, or those that Turkey bans to protect its own industries, a thing that applies not only to northern Syria but to the rest of the world, al-Masri added.

Syrian merchants do not pay tariffs for goods exported to Turkey or through Turkey to other areas, al-Masri added, because a joint committee has set up the involved fees to affect neither producers nor consumers.

Turkey buying Syrian crops

Imports from northern Syria to Turkey, according to minister al-Masri, include olive oil, surplus wheat, barley, cotton, corn, and potatoes. Such goods enter Turkey unconstrained and are sold in the markets there.

Commercial exchanges between Turkey and northern Syria started with opening three border crossings between Turkey and Aleppo’s countryside over two years. In 2018, Turkey also decided to purchase the entire potato harvest from Syrian farmers, to help the latter sell their crops and address one of its markets’ needs and decrease local prices.

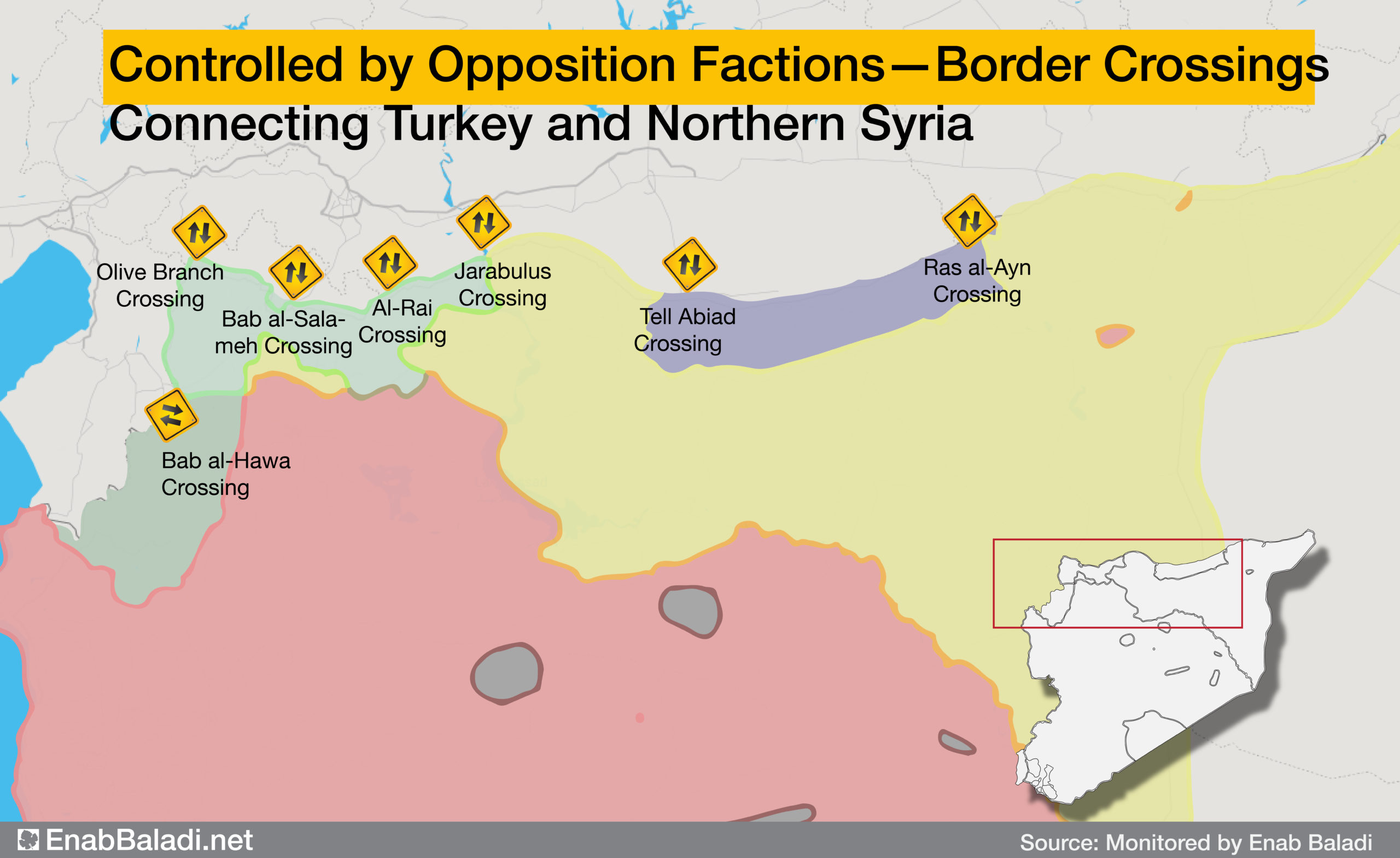

The Bab al-Salameh crossing was opened in 2016; Jarabulus crossing in September 2016; and al-Rai in December 2017. Al-Rai was the first civilian-commercial border crossing between Turkey and northern Aleppo.

The decision to export crops other than potatoes to Turkey was left to Syrian farmers, regardless of these crops’ prices in local markets or those already set up by Turkey.

Turkey also has been buying grain from Syrian farmers through the Turkish Grain Office (TMO), run by the Turkish Ministry of Agriculture. The TMO pays the farmers the price of procured grains.

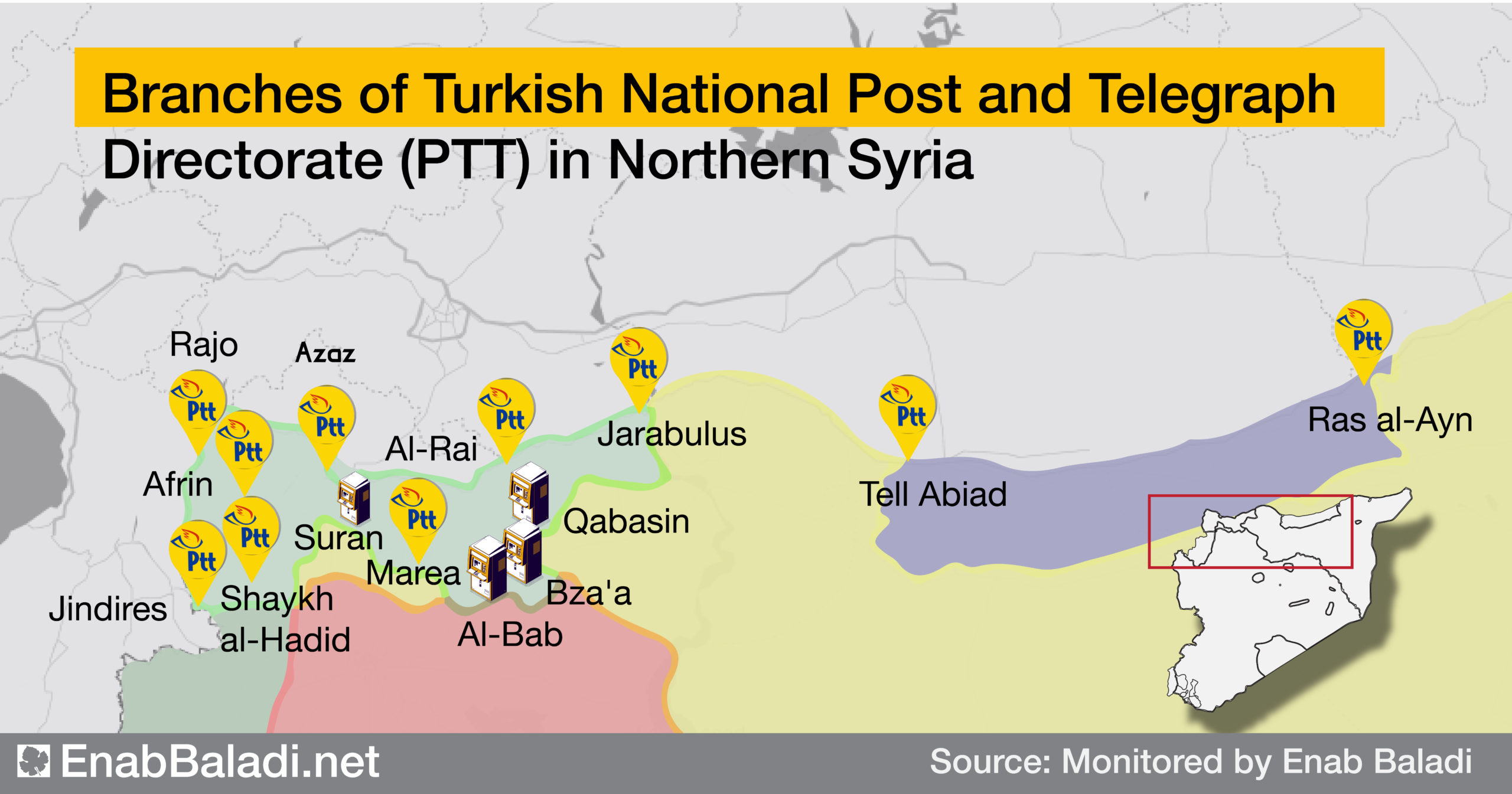

The payment process is handled by the Turkish Post and Telegraph Directorate (PTT).

Local councils in the region help farmers open accounts with the PTT to receive their grain prices.

Crop exports involve other procedures. Before selling their crops to Turkey, farmers should first obtain a certificate-of-origin certified by the relevant local council. Farmers also have to define the exact amounts to be exported in advance. Additionally, they must be holders of Identity Documents issued by local councils and own a bank account with the PTT.

When it comes to wheat, the agreement provided that Turkey will buy only the “surplus,” the SIG’s agriculture minister Abdulhakim al-Masri said.

Lately, Turkey has exempted Syrian farmers from grain entry tariffs to improve the finances of farmers in northern Syria, the minister added.

When farmers fail to sell this year’s grains; they will not be able to sell grains the next year as well. Simultaneously, the exported grains are meeting the Turkish market’s demands, the minister added. “There is a mutual benefit here. The advantages are not limited to one party only.”

The minister added that foreign trade is not bringing advantages to Turkey alone. All involved parties are reaping benefits. He pointed to commodities across northern Syria, 90% of these are brought through Turkey.

Some of these products are Turkish; others are imported to the area from other countries through Turkish transit routes, including oil products. Turkey does not make any revenues from transited products because it has not imposed any tariffs on commodities passing in through the borders.

Turkish government directorate operating in Syria

After the Turkey-backed armed opposition groups seized control over the western countryside of Aleppo, as well as the two cities of Tell Abiad and Ras al-Ayn in northeastern Syria, local councils started rehabilitation of the area on various levels, particularly economy and service sectors. These efforts were supervised and funded by Turkey.

When military Operation Euphrates Shield ended, launched by Turkey and armed opposition groups in the cities of al-Bab, Azaz, and Jarabulus, against the Islamic State (IS), the Turkish government opened the first branch of the Post and Telegraph Directorate (PTT) in Jarabulus city, northeast Aleppo.

The Turkish government then set up five additional branches across areas held by the opposition armed groups and in the two cities of Tell Abiad and Ras al-Ayn, installing ATM machines too.

The PTT manages financial operations of crops sold to turkey, paying farmers prices of wheat and barley through the PTT accounts they have opened earlier.

The Turkish government forced organizations operating in Aleppo, both local and international, to transfer money exclusively through its PTT branches in Syria.

Turkish directorates, including the PTT, have become northern Syria’s “bloodline.” These directorates are running a banking system and operating as an alternative to absent banks in the area, researcher in economics Firas Shaboo told Enab Baladi.

Several organizations working in Turkey depend on PTT to send money to northern Syria; merchants also resort to PTT to conduct safe transfers.

In addition to the PTT, many private Turkish companies have been operative in the northern countryside of Aleppo. These started service projects aimed at helping the area’s population. AK Energy is one such company, providing opposition-held areas with power under contracts signed with local councils.

Services provided by PTT centers in northern Syria

|

TL in the currency basket

Having rolled out its currency in northern Syria, is Turkey profiteering?

When the Syrian Pound (SYP) hit a new low in June 2020, local authorities, the Interim and Salvation governments, in Aleppo countryside and Idlib city started looking for alternatives to address inflation and spiking prices.

The two governments decided to use the Turkish Lira in their control areas, along with the Syrian Pound and the US dollar. The Salvation government has even adopted the Turkish Lira as the only currency, dropping the Syrian Pound from the currency basket. The Interim government also adopted the Turkish Lira; however, it has so far kept the Syrian Pound in use.

Nine months have passed since Turkey rolled out its currency in northern Syria, but this measure has failed to solve the dilemma of the skyrocketing price, while it confused the population which today has three currencies to use.

Speaking of revenues, the Turkish economy has probably made some profits with the spread of the Turkish Lira in northern Syria. However, these revenues remain too little, researcher in political economy Yahya al-Sayed Omar told Enab Baladi.

The Turkish economy is vast compared to northern Syria’s, not to forget that Turkey is a member of the G20 and has adopted an economic policy oriented towards establishing relations with countries, such as China and Germany. This is why the role of northern Syria’s economy has been diminishing its Turkish counterpart.

The Turkish gross domestic product (GDP), according to the World Bank data, is 750 billion dollars, the GDP in northern Syria, even though there are no official figures, is unlikely to exceed several million dollars, so it is very “modest” when compared to Turkey’s. Accordingly, Turkey could not be waiting for real profits as it partners with northern Syria. This partnership is clearly in northern Syria’s favor, the researcher added.

The circulation of the Turkish Lira in northern Syria might decrease its supply in the Turkish market and enhance its value to some extent. But this impact on the Lira’s value remains very little, almost nonexistent, because the small economy in northern Syria demands limited circulation of the Lira. Turkey cannot count on this demand as a chief factor to influence the Lira’s supply, researcher al-Sayed Omar added.

Even though the spread of the Turkish Lira in northern Syria might boost Turkey’s foreign trade, as it paves the way for Turkish products’ transfer into Syrian markets, Turkey cannot place reliance on these transfers because it has foreign markets to which it exports commodities worth millions. It will not lean on a market which demands amount only to few millions.

While the Turkish Lira circulation had a positive, but little impact, on the Turkish economy, a vaster positive impact could be observed within northern Syria’s economy, which benefited from the relative stability of the Turkish currency and recently its improvement, the researcher added.

On 26 February, the TL was sold for 476 SYP and purchased for 469 SYP, according to the currency convertor the Syrian Pound Today.

Mutual economic interests:

Northern Syria is the weakest link

Firas Shaboo-Researcher in Economics

Turkey is northern Syria’s only channel to import commodities and export goods to other countries. There are a few commercial openings with the regime-held areas and others with the Autonomous Administration areas, but these are less operative and barely effective.

The absence of entities that usually regulate business, build economies, or control sectors of finance, economy, commerce, industry, and agriculture has been northern Syria’s economy’s chief problem. What exists in northern Syria today is a number of municipalities and local councils.

Worse yet, ministries and directorates in northern Syria “are mere offices; titles larger than their actual size.” Due to this, Turkey has pumped massive amounts of currency into local markets and contributed to establishing infrastructure or grounds for a structure to help the economy grow in northern Syria.

It is in Turley’s best interest to bring the affairs of the areas it is supervising into a state of order, so as to achieve some extent of security and economic stability, which in turn would lay the ground for a better environment to mitigate tension and limit emigration towards its territories.

The circulation of the Turkish Lira in northern Syria’s areas has been exaggerated, for the Syrian Pound is still in use, even though it is the weakest and despite everyone’s efforts to get rid of it. Additionally, there has been large-scale dollarization in the area. The Turkish Lira ranks second after the US dollar. There is also the difficulty to obtain smaller denominations of the Turkish currency, which has been hampering its use.

|

Turkey seeks to benefit from the little abundance in northern Syria, in exchange for goods, making it a relationship based on mutual interests.

The two sides recognize that benefits are reciprocal. However, the weak party in this relationship is northern Syria. Consequently, Turkey has been the one to impose conditions, control crossings, and determine the type of goods that move through these crossings. It is why Turkey has been holding the reins to the economy in northern Syria.

This has been the situation because the “liberated areas’” relationship with the crossings of the Syrian regime and the Autonomous Administrations is not fairly good. The opposition has been denied access to all its needs from these areas, which suffer from some shortages themselves. Therefore, northern Syria has been fully adhering to Turkey’s conditions regarding economic, commercial, and industrial matters.

Today, there are no companies, infrastructure, or massive industries that northern Syria can rely on. The existing production, at its best, is agricultural or limited to minor products. There are also a few professions and industries, mostly vocational or half-developed. As a result, Turkey’s margins of benefit are not exactly as rumors have it.

The Turkish economy is larger than this geographical spot and its ability to refresh the Turkish economy or provide it with significant resources.

This spot is simply a market for Turkish commodities, and it is difficult to say that it will revive the Turkish economy. However, these activities are supplying the Turkish treasury with some revenues and are solving northern Syria’s population’s problems.

This is a reciprocal relationship that helps northern Syria sell some products, mostly food commodities, and import some others from Turkey. Should this continue for a longer time without intervention from officials, northern Syria will reach the stage of ultimate dependence on Turkey. This will be a disaster that will lead to high rates of unemployment and economic dependence.

if you think the article contain wrong information or you have additional details Send Correction

النسخة العربية من المقال

-

Follow us :

Trucks transporting goods and relief aid through the Bab al-Hawa border crossing (Edited by Enab Baladi)

Trucks transporting goods and relief aid through the Bab al-Hawa border crossing (Edited by Enab Baladi)

A

A

A

A

A

A

More In-Depth

More In-Depth