Zeynep Masri | Saleh Malas | Hussam Mahmoud

The 41st Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) summit, held on 5 January, in al-Ula city, west of Saudi Arabia, has turned the page on the Gulf crisis, marking the end of the three-year feud.

Hailed by reopening land crossings by Saudi Arabia and Qatar, the Summit of Sultan Qaboos and Sheikh Sabah highlighted Kuwait’s role as it played the mediator between the parties to the Gulf dispute, seeking to end the rift.

Syrians, for their part, followed the summit’s progress, hoping to find in its outcomes any potential impact on the Syrian affairs, for even though Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Qatar have been less active in structuring the Syrian landscape lately, the Gulf reconciliation might influence the Syrian regime’s advocates.

This investigation draws on interviews with political analysts and economists, who addressed the political, military, and economic out-turns of the Gulf crisis resolution, as pertaining to parties to the Syrian conflict and their allies.

Al Ula statement: nothing new regarding Syrian regime

At the onset of the 2011 revolution, Saudi Arabia, UAE, Bahrain, and Qatar adopted a unified attitude towards the Syrian regime. Doha, with blessings from Riyadh, was the chief player in setting the region’s politics into motion.

In 2012, Qatar, Saudi Arabi, and the UAE closed their embassies in regime-held areas, protesting the excessive force used against civilians and the rising death toll.

Three months after the start of the Gulf diplomatic crisis, former Prime Minister of Qatar, Hamad bin Jassim, appeared on Qatar TV. He pointed to mistakes committed in funding Syrian armed opposition groups.

Riyadh also sponsored opposition-affiliated factions, particularly Jaysh al-Islam, which operated in Ghouta under the command of Zahran Alloush.

The Qatar blockade, however, was a turning point. The Gulf attitude towards the Syrian regime softened. States that boycotted Qatar accused it of funding hardliner groups in Syria, and both UAE and Bahrain reopened their embassies in the regime’s areas in late December 2018, even though a political settlement has not been reached on the situation in Syria yet.

The Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi, Mohammed bin Zayed al-Nahyan, called the Head of the Syrian regime, Bashar al-Assad, on 27 March 2020, confirming the UAE’s support for Syria and its people under these exceptional circumstances, referring to the COVID-19 outbreak and the deterioration of the healthcare system.

“Syria, the brotherly Arab country, will not be alone in these delicate and critical circumstances,” he stated.

The leaders of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) member states at the Al Ula summit held in Saudi Arabia — 5 January 2021 (Reuters)

The Al Ula statement, issued on 5 January, summed up the event’s outcomes, stressing that UN Security Council Resolution No. 2254 remains operative. The resolution lays the ground for the political solution in Syria, namely changes in the current ruling authorities. The statement also reiterated the refusal of Iran’s intervention in the region’s affairs.

These statements, nevertheless, are due to complicate Abu Dhabi’s and Manama’s political course of action since they have reopened their embassies in Syria, in a first Arab step on the path to normalization of ties with the Syrian regime and its political rehabilitation.

The GCC summit is irrelevant to the Syrian situation, and the Al Ula statement has brought about nothing new regarding Syria, Syrian researcher and political author, Majed Aloush said. “What is left of the Syrian regime is just a facade that Russia needs to justify its continuing presence in Syria.”

“It would be an exaggeration to say that Gulf states have normalized ties with the Syrian regime. A more realistic description of the situation is that Abu Dhabi and Manama attempted to win over the regime to find a gap in al-Assad’s relations with Tehran,” the researcher added.

Regionally, the situation in Syria is “extremely convoluted,” the reason why all parties “are in dispute and maintain links at the same time,” the researcher added. The Arab states have abandoned the Syrian affair since the 2017 agreement of de-escalation and as Turkey took center stage in deals with Russia and obtained the loyalty of several opposition factions.

As such, the GCC summit’s statement cannot be viewed as posing a challenge to a potential convergence between the Gulf states and the Syrian regime, particularly since Saudi Arabia is more likely to follow in Abu Dhabi’s and Manama’s diplomatic steps.

Tehran’s support for the Syrian regime remains contingent on Qatar’s serious position of the reconciliation, the new U.S. administration’s objectives, and Turkey’s standing on the resolved dispute, as well as the Gulf-Egypt reaction to the Qatar-Turkey relations, and the extent to which they might welcome this relation, Aloush said.

How did the Gulf crisis start?

On 5 June 2017, Saudi Arabia, UAE, Bahrain, and Egypt severed diplomatic ties with Qatar, closing Qatar’s sole land border, preventing its ships from docking at their ports and aircraft from entering their airspace. Tension started after Doha was accused of sponsoring extremist groups in the region and seeking rapprochement with Iran, which is, in turn, accused by Arab countries of interfering in national affairs.

Qatar is funding “radical ideology,” former President Donald Trump tweeted on 6 June.

On 23 June 2017, the states involved in Qatar’s isolation provided the Kuwaiti arbiter with a list of 13 demands, which he was to forward to the Qatari leadership. A deadline, 10 days from submission, was set up for Qatar to adhere to the said demands, but the Saudi Ministry of Foreign Affairs prematurely announced that Doha “did not observe its obligations, and all efforts were to no avail,” CNN reported.

Based on U.S. recommendations, Kuwait insisted on playing the intermediary, led by the deceased Prince Sabah al‑Ahmad al‑Jaber al‑Sabah.

Kuwait sought to lift the ban on Qatari flights, imposed by Saudi Arabia and the UAE. These attempts were doomed for failure too.

The air blockade was eventually taken to the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), but Saudi Arabia and the UAE appealed that only the International Court of Justice (ICJ) has the authority to decide on this dispute.

On 14 July 2020, the ICJ did not uphold the complaints by the two plaintiff Gulf states, ruling that ICAO is competent to hear the case. Qatar welcomed the decision and officials expressed their confidence in the ICAO’s authority.

On 6 December 2019, in a speech delivered during the Mediterranean Dialogues forum, the Qatari Minister of Foreign Affairs, Mohammed bin Abdul Rahman Al Thani, said that discussions with Saudi Arabia have brought about a good measure of rapprochement.

On 14 October 2020, Saudi Arabia reiterated that a solution to the Gulf crisis is “near at hand.”

Saudi Arabia’s efforts to close ranks represent all four countries, twitted the UAE Minister of State for Foreign Affairs, Anwar Gargash, on 8 December 2020.

On 6 December 2020, Bloomberg quoted Saudi and Qatari officials, who said that the two countries are looking forward to positive outcomes of the U.S.-Kuwait mediated talks. These efforts materialized in Al Ula statement, which declared the end of the row between Qatar and the other four Gulf states.

Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia, Mohammed bin Salman, with Emir of Qatar, Tamim bin Hamad, on the day of the Gulf reconciliation in Al Ula city, Saudi Arabia — 5 January 2021 (Saudi Press Agency)

Syrian opposition’s political course: indirect changes following Gulf reconciliation

The Al Ula statement presents a political opportunity, whereby the Gulf’s standing on the Syrian affairs can be operative again, as to “support Syrians’ rights and impose necessary pressure to trigger the political solution in Syria” under the provisions of the UN Security Council Resolution No. 2254, President of the Syrian National Coalition, Naser al-Hariri, said in a statement published on the coalition’s official website.

Hadi al-Bahra, co-president of the opposition’s side of the Constitutional Committee, said that Al Ula statement of the 41st GCC summit is “a step on the path to resolving disputes …, which is to give rise to more balanced policies and greater support for Syrians.”

The resumed Gulf relations will “undoubtedly” have an impact on the Syrian situation, “particularly since the Gulf countries, most notably Saudi Arabia and Qatar, are among key supporters of Syrians’ aspirations and revolution,” said Head of the High Negotiations Committee (HNC), Anas al-Abdah.

In 2015, Riyadh was tasked with forming the Syrian opposition’s delegation anew. The delegation will later engage in negotiations with the Syrian regime regarding the political transition and the post-conflict phase in Syria. Outcomes of Saudi Arabia’s task were the HNC, the body laying down political guidelines for the opposition, and the negotiation delegation, formed under the committee.

Drawing on political changes, the NHC was reformed during the Riyadh II Conference, held on 22 November 2017. The committee was joined by the opposition-affiliated Cairo and Moscow platforms, as well as independent Syrian figures.

The Moscow and Cairo platforms’ entry into the committee was a subject of criticism, though it was enabled by a provision of resolution 2254.

However, members of the committee still came up with a vision, unified to some extent. Subsequently, legal, media, detainees sub-committees were established.

In 2019, the committee’s list of independents was a major source of controversy; it even resulted in a crisis of its own when Riyadh hosted a group of Syrian figures intending them as a replacement of the already existing list. This was Saudi Arabia’s attempt to preserve its influence within the committee.

Saudi Arabia’s efforts to ensure presence within the committee through the list of independents is related to potential decision-making privileges, which would enable the kingdom to limit Turkey’s powers—Turkey is the chief sponsor of the Syrian National Coalition, the committee’s largest body political—political analyst Hassan al-Nifi told Enab Baladi.

The NHC consists of 38 members. In addition to seven independents, other members are delegated as follows: eight by the National Coalition, four by the Cairo platform, four by the Moscow platform, seven by the armed opposition groups, and five by the National Coordination Committee for Democratic Change (NCC).

“The outcomes of the intra-Gulf reconciliation might influence the Saudi-Turkish relations. This influence, however, will not directly affect the NHC,” because the division within the NHC can be independently addressed under the management of Anas al-Abdah, the analyst added.

The Al Ula statement might as well outline several options to bring back the Gulf-Turkey relations into normal. This might have an impact on several regional issues, including the political process in Syria.

Nuancing the summit’s outcomes, in addition to the Gulf’s advocacy of a political solution in Syria in line with the UN guidelines “is true support for the Syrian cause,” al-Nifi added, even though the Gulf standing on the Syrian situation is in alliance to the U.S. administration, and rarely diverts from it.

“It would be very positive if the U.S. continues to press the regime, for it will encourage other states to adopt a similar course of action,” he said.

It is largely believed that the political solution in Syria will be the result of an international consensus between parties to the Syrian issue, based on these parties’ interests and in harmony with their visions. The GCC states do not have an immediate role in shaping up the political process in Syria.

Would certain politicians return to opposition’s forefront?

Two days before the Riyadh II Conference was held to restructure and expand the opposition delegation, the back-then General Coordinator, Riad Hijab, resigned from the HNC, with other eight opposition figures.

At the time, Syrian opposition officials attributed the resignation to Saudi Arabia’s pressure on the committee; others linked it to the kingdom’s attempts to form an opposition delegation that would accept Bashar al-Assad’s stay in office, through including the Moscow platform—considered an affiliate of the opposition, whose leanings are towards the Syrian regime’s narrative of the happenings in Syria.

Hijab was elected the general coordinator of the HNC in 2015 and threatened to leave the position should the committee change its demands.

“I will not be a member of any political body that does not preserve the demands of Syrians and the constants of the revolution, or in case the committee is changed or reconstituted including personalities whose highest requirements are not those of the Syrian people. There is no place for me with such personalities,” Hijab said in an interview with Al Jazeera in September 2017.

In July 2020, Hijab returned to the Syrian political arena, having kept a low-profile for three years. He railed against the work of opposition bodies that need reconfiguration, restructuring, expansion of their scope of representation, as well as ensuring that their activities are not bounded to any political agendas.

The Gulf crisis, nevertheless, was not the immediate reason why Hijab disappeared from the Syrian political domain, al-Nifi said. He rather quit having recognized that the national decision has become increasingly “hinged on the regional and international interests and wills. Accordingly, Hijab did not wish to be a false witness to the concessions and deviations from the Syrian rights.”

Al-Nifi added that Hijab is unlikely to come back to political work as a chief actor on behalf of the opposition following the resolution of the Gulf crisis. He will not return any soon since the factors that made him quit in the first place still exist.

These factors are the parties within the NHC that do not observe the “revolution’s basic principles,” that Hijab refers to in political initiatives he runs. These principles centralize on keeping the Head of the Syrian Regime, Bashar al-Assad, out of the transfer of power in the post-conflict phase.

The UAE flag hoisted on the embassy flagpole in the Syrian capital Damascus — 27 December 2018 (ZUMA Press Ammar Safarjalani)

Reverberations within Syrian conflict map: existing, but limited

The UAE provided the Syrian armed opposition groups with military support, particularly in Daraa city, south of Syria. Support was channeled through the Military Operations Center (MOC), operated by the U.S.-led coalition.

Another armed group that the UAE financed was the Syrian Revolutionaries Front, one of its commanders was even nicknamed Abu Ali al-Emirati.

The UAE played a major role in supporting Ahmed al-Awdeh, commander of the 5th Legion. Turning on various armed opposition groups, al-Awdeh was able to organize public facilities and the service sector in Daraa city. He also established the Police Service and Traffic Police Department, with support from the MOC and the UAE, which he accessed through his family relations to Khaled al-Mahamid, UAE-based former Deputy President of the HNC.

The MOC is a foreign military operations room and command center, led by the U.S. and its allies, including France, the UK, Jordan, and a number of Gulf states. It was founded in 2013 and developed in 2014, encompassing several factions of the Free Syrian Army (FSA), that operated in Daraa, Quneitra, Rif Dimashq, and northern Aleppo countryside.

Under the provisions of the “settlement” agreements it promoted in Daraa province in 2018, Russia succeeded in creating a devoted military body that took over a vast area in the province’s eastern suburbs—that is the 5th Legion.

The central role that Russia and the UAE are playing in southern Syria cannot be linked to the Gulf reconciliation, Nawar Bulbul, researcher and Chief Information Officer at Omran for Strategic Studies, told Enab Baladi.

Consequently, the Emirati role within any settlement of the security situation in Daraa will not be affected by the outcomes of the Al Ula summit, except for its relation to Iran’s presence and influence in the region. The Al Ula statement emphasized that it “rejects Iran’s presence in Syrian territories and Tehran’s intervention in the Syrian affairs.”

Statement signatories also demanded the removal of Iranian forces and Iran-backed militias from Syria.

An international conflict is being run in Syria through local proxies to enable one party to tighten its military and security grip over the southern region in Syria. This conflict is manifesting in local arrests and assassinations in the south.

Today, Russia is closer than ever to holding reins to power and security in southern Syria, researcher Bulbul added.

As for military action in northeastern Syria, it is affected by several factors unrelated to the Gulf crisis, though some of the involved Gulf states have partially directed the course of action. These factors govern the role of the military factions operating in the areas in question and have pushed the Gulf states out of the control scope. These factors are the international joint interests of Turkey, Russia, and Iran, as well as the American partner.

Saudi Crown Prince, Mohammed bin Salman, greets Emir of Qatar, Tamim bin Hamad, upon his arrival to attend the Al Ula summit west of Saudi Arabia — 5 January 2021 (Saudi Press Agency)

Blockade or normalization: would the Gulf reconciliation affect Syria’s economy?

Addressing the situation in Syria, the Al Ula statement confirmed the GCC’s countries’ commitment to the articles of the First Geneva Convention and the UN Security Council Resolution No. 2254, as a frame for the political solution in Syria. The statement, however, laid down no further decisions that might bring any changes to the Syrian economy.

There are no explicit economic agreements between the parties to the Gulf summit and the government of the Syrian regime, given the U.S. economic sanctions under the Caesar Act, which prevent countries from conducting business with the regime.

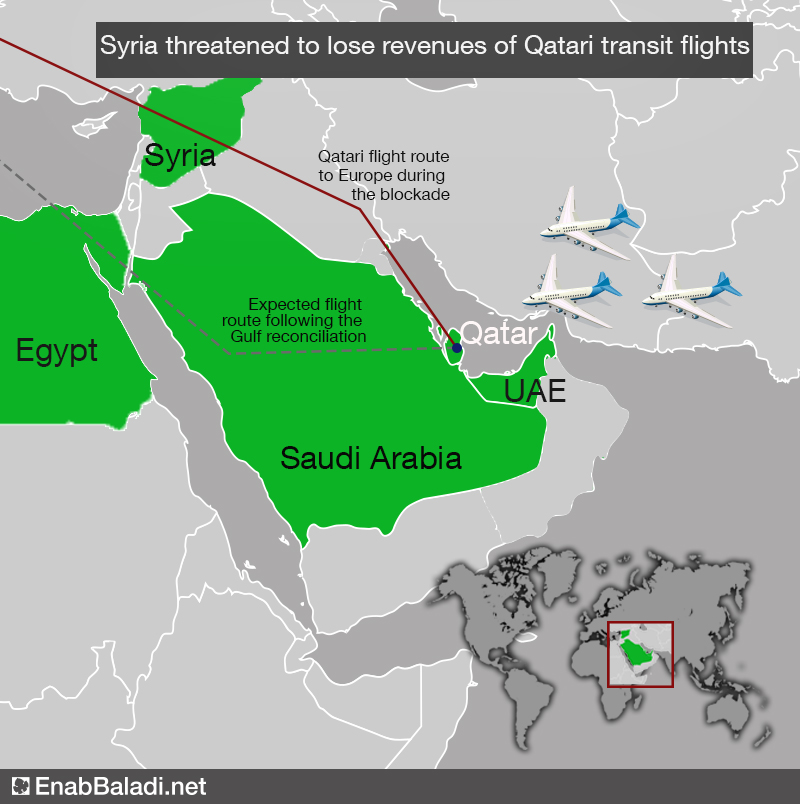

And despite Qatar’s boycott drive against the regime, Qatari aircraft still used the Syrian airspace during the aerial embargo Qatar suffered due to the feud with other Gulf states.

This is in addition to the fact that Gulf countries continue to import Syrian crops, including vegetables and fruit, and products, such as clothes.

Gulf states will probably not seek more commercial openness with the Syrian regime following the Qatari-Saudi reconciliation; rather, they will adopt an attitude that would press towards a political solution and enforcement of western sanctions, Karam Sha’ar, Syrian economist and scholar at the Washington-based Middle East Institute, told Enab Baladi.

The UAE has lately sought such economic rapprochement with the Syrian regime, but the U.S. administration pressured the UAE state to end these efforts.

Some restrictions have been imposed on Syrian importers, but the Arab countries, most prominently Gulf countries, are the Syrian products’ only market in the meantime. This is an additional card that the Arab states can use to pressure the Syrian regime. But they have been unwilling to use it so far, Shaar added.

Gulf states actually cannot offer the Syrian regime financial assistance, though some are willing to do so. Nothing is stopping them from providing such help other than external factors, most notably the Caesar Act, economist Khaled Tarkawi told Enab Baladi.

Also, the UAE’s promises to support the Syrian regime, which were made by the Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi, Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, in March 2020, were not met, at least not explicitly.

Would Qatari aircraft change their course?

On the heels of the Al Aula summit, the UAE Undersecretary of the foreign affairs ministry, Khaled Belhoul, said that his country will end all measures against Qatar, allowing it accesses through land, sea, and air, as of January 9, reported the Emirates News Agency.

On Twitter, Qatar Airways announced resuming flights through Saudi Arabia’s airspace after three years of interruption.

The tweet was posted on Thursday, 7 January, the day on which the first scheduled flight was carried out from the Qatari capital, Doha, to the city of Johannesburg, in South Africa. This raised the question of whether Qatari airlines would abandon the Syrian airspace after the Ministry of Transport of the regime’s government granted it aerial access in April 2019.

Back then, Qatar justified using the Syrian airspace with the blockade imposed by Gulf neighbor states.

Despite the almost overall rupture in relations between Syria and Qatar, the Group CEO of Qatar Airways, Akbar al-Baker, in May 2019, attributed flights through Syria to the blocked. “We are under siege, so we have to find ways to meet our country’s needs. It is that simple.”

While flight route changes inflicted significant annual losses on Qatar, given the high costs and long flight durations, the former Minister of Transport of the Syrian regime’s government, Ali Hammoud, said that the Syrian treasury would make over $30 million annual revenues from lending Qatar airspace. The figures were reported exclusively by the Syrian government, for Qatar did not make public the involved costs.

Because many airlines stopped landing at Syrian airports or conducting flights through the Syrian airspace for political considerations, the Civil Aviation Corporation took action to boost its revenues and make maximum use of Syria’s geographical location. In May 2019, the corporation increased navigation services charges by 50 percent and offered privileges to aircraft flying through the Syrian airspace without landing.

Under the new charge amendments, aircraft pay a standard $150 fee per flight, for aircraft that weigh less than 75 tons. For aircraft weighing between 76 and 200 tons, an additional $ 2.10 will be charged per extra ton and $ 2.4 per extra ton for aircraft weighing 201 tons and above.

The Qatari flights return to Saudi airspace brings into question the potential end of the Qatari-Syrian aviation agreement in the wake of the Gulf reconciliation and thus the Syrian regime’s loss of one source of foreign currency, under the U.S. and European sanctions and the economic crises it is suffering, which tightened Syrians’ finances by force of high prices, weak purchasing power, and severe devaluation of the Syrian pound.

The Syrian regime’s essential revenues from the Qatari flights will dry off should the regime demand charges from Qatar following the Gulf reconciliation, economist Tarkawi said.

This Tarkawi attributed to the fact that Qatar aircraft were passing through the Syrian airspace to overcome an emergency since the other Gulf region airspace was blocked, adding that Qatar was not paying a fixed fee even though the regime announced otherwise.

Syrian products in Gulf markets

The Saudi and Emirati markets are of the very few options the regime was left to sell Syrian products, food items, and clothes, as it failed to bring imports and exports to their former status, hindered by the Caesar sanctions.

Saudi authorities allowed Syrian trucks loaded with Syrian goods to enter its territories after goods were brought in loaded on non-Syrian trucks. Authorities passed a decision granting Syrian drivers a visa to cross Saudi borders in November 2020.

Including vegetables, fruits, Syrian commodities are rarely lacking in Saudi local markets, while citizens across Syria have limited access to various domestic products given their poor economic conditions.

Syrian exports flow smoothly through Saudi ports to the local markets, adhering to customs procedures applied, in line with Saudi regulations, to trucks from all countries alike, Asharq Al-Awsat newspaper reported quoting the Saudi General Customs Authority.

Saudi authorities have also allowed Syrian trucks to pass through their territories to other Gulf countries, Director of the Syrian Federation of International Freight Forwarders, Najaw al-Sha’ar told the Russian Sputnik news agency in September 2020.

Economist Tarkawi pointed that Saudi Arabia is not offering the Syrian regime any official assistance, for commercial relations between the two countries are limited to the access Saudi Arabia has granted to some trucks loaded with fruits, vegetables, or food products such as cheese, and milk into its local markets, stressing that these transactions are even conducted directly with Syrian merchants, unmediated by the regime’s government.

Though limited, the said access will continue to be permitted by most of the Gulf countries and encouraged by the Syrian regime, the economist added.

if you think the article contain wrong information or you have additional details Send Correction

النسخة العربية من المقال

-

Follow us :

A

A

A

A

A

A

More In-Depth

More In-Depth