Zeynep Masri | Saleh Malas | Sukaina Mahdi

In 2020, the Syrian economy continued to struggle just as it did the year before.

The unchanged economic indicators and the decisions of the Syrian regime’s monetary authorities, both signify that, in 2021, Syrians will still suffer the burdens of unresolved former economic crises.

No alterations can be detected in the regime’s economic or financial policies, even though concerned officials have been making promises to end turbulence for years. But these promises are only meant to “numb” the citizens in regime-held areas.

In this article, Enab Baladi addresses the economic crises that gripped Syrians throughout 2020, which continue to overwhelm them in the new year.

Several economic experts and researchers are interviewed, who discussed a potential deterioration in the country’s economic conditions, given the Syrian regime’s economic and financial resolutions.

Unmet promises: no measures to bridge wage-price gap

Rejecting all proposed political solutions, while showing even less commitment to the United Nations’ resolutions regarding ending the conflict in Syria, the regime was subject to various European and U.S. sanctions in the past few years. These punitive measures tightened the grip over the regime and strained its economy.

Another blow to the Syrian economy was dealt by the COVID-19 pandemic. The virus hit all sectors of the economy, with the preventative measures the regime adopted to flatten the curve.

These measures were shortly loosened to jumpstart the economy, already hampered by sanctions.

For Syrians, this meant a life that is all about an ongoing rise in the prices of necessary commodities; the inability to afford these commodities; the collapse of the national currency; and the devaluation of salaries and wages.

Pays still the same

A month has passed since the regime approved the 2021 general state budget; nearly three months have passed since the Syrian Prime Minister, Hussein Arnous, has promised to fulfill the pay increase recommended by the regime’s Ministry of Economy. The regime, however, has not issued the increase decision yet.

Discussing the Draft Budget Law, the People’s Assembly-affiliated Budget and Accounts Committee stressed that it is necessary to increase wages and salaries of state staffers, particularly since an increase provision has been added to the draft budget. Salaries are to be increased by 45 percent, the pro-regime al-Watan newspaper reported on 13 December 2020.

Under the 2021 general state budget, ratified by the People’s Assembly and approved by the President of the regime, Bashar al-Assad, 1018 billion Syrian Pounds (SYP) is determined as salary and wage allocations. An additional 3500 billion SYP are to be invested in social support, and 50 billion SYP in the National Social Aid Fund.

Though significant, these figures still fail to cover the citizens’ needs. These allocations can barely stand the SYP to the U.S. dollar exchange rate discrepancies.

The gap between pays and costs of living is widened by the regime’s recent policy of military service exemption fee, which has adopted the black market’s exchange rate. Merchants are also permitted to price their goods according to the black market’s rates, while pay allocations continue to be determined under the state’s official exchange rate.

Exchange rates hit a stable mark of 1200 SYP per U.S. dollar, weekly reports of the Central Bank of Syria (CBS) have demonstrated. But such stability too rarely is achieved in the black market, with rates amounting to nearly 3000 SYP per U.S. dollar.

Disadvantageous support

Wage and salary allocations are among the state’s binding commitments, which should not be delayed at times of economic upheaval. Such increases, which are to support citizens, have long-term effects, for the state cannot repeal salary raises when sufficient revenues are not realized. The state might even be forced to rely on its financial reserves to meet future financial obligations.

State employees demand such increases to survive the repeated price hikes, which have been taking an upward trajectory since the beginning of 2020.

However, any pay increase, should it be enforced, would cause further price spikes; drops in currency value; unprecedented levels of inflation; and a fall in people’s purchase power amid current circumstances—namely the depleted resources; disrupted production; sanctions imposed on the regime, and the COVID-19 pandemic.

The increase’s disadvantages are not limited to beneficiaries. Non-state-employees and people who run their own business will also suffer its woes.

The pay increase opens to discussion issues of fair distribution of income, which might cause persons, unaffiliated with state sectors, major losses, particularly lower-income and unemployed groups.

In Syria, the lowest average of salaries is 37,000 SYP (nearly 12 USD), indicates SalaryExplorer.

And populating one of the world’s poorest countries, 90% of Syrians are below the poverty line, according to Dr. Akjemal Magtymova, the World Health Organization (WHO) Representative to Syria.

To exit this deadlock, the Syrian regime must invest more effort to cover the basic needs of residents in its areas.

The regime should treble the expenditures it allocated to these needs in 2020; relative regime’s entities must also focus on the population’s immediate needs through social and aid programs to prevent a famine, a December 2020 study by the Atlantic Institute stressed.

The study addressed the deep problems within the regime’s 2021 general budget, suggesting that the regime should seek to fix market prices or decrease them, instead of the planned pay increase.

A woman selling bread in al-Muhajreen area in Damascus city — October 2020 (Lens of Young Damascene)

Bread siege: insufficient wheat production in regime-held areas

In the past few months, photographs of people standing in long lines in front of bakeries in regime-held areas went viral on the internet again.

Syrian authorities implemented a new distribution mechanism for subsidized bread, with an allocation between one to four bread bundles per family, per day, depending on household size.

To reduce queues in front of bakeries, the Ministry of Internal Trade and Consumer Protection changed the bread distribution policy, people allocated a bundle per day were to get two bundles every other day. This, the ministry attributed, to its efforts to manage the overcrowding.

In the regime areas, flour has been a rare commodity as well, which made the bread crisis and the regime’s role in worsening the situation trend discussions, along with the Syrian Pound, fuel, and transportation crises.

Under the new mechanisms, bundles are allocated as follows: one bundle to families of one or two members; two bundles to families of three or four members; three bundles to families of five or six members; and four bundles to families of seven or more members. A bundle contains seven flat loaves.

The ministry has banned the sale of bread bundles unless it is to holders of the smart car. However, it permitted bakeries to sell 5 percent of their daily production to specific groups. Persons without a smart card can purchase a single bread bundle per day.

This exceptional group includes students and employees serving in places other than their provinces of registration, among others.

The selling processes which are not mediated by the smart card are conducted according to a state-provided list, with the person’s name; national number; and contact information.

“Because it is difficult to provide citizens with basic substances, or afford these substances’ increasing prices due to the western sanctions imposed on the regime,” the General Organization for Trade and Processing of Grain said it has organized several calls for tenders in 2020 to purchase wheat needed for flour and bread production.

The regime authorities have been providing wheat either by purchasing it from farmers or importing it under contracts they sealed with Russia.

In 2019, the Syrian wheat production decreased from nearly four million tons to less than 1.5 million tons. The regime’s shares are estimated as less than 400,000 tones. The rest of the wheat crops are distributed to areas held by the opposition and al-Hasakah that is controlled by the Syrian Democratic (SDF), given that al-Hasakah is the country’s chief wheat reservoir, analyst Adnan Abdulrazaq told Eanb Baladi.

Living crises reveal regime’s impotence

Living crises reveal regime’s impotence

In early December 2020, the director of the Syrian Bakeries Foundation blamed the bread crisis and the queues in front of state-run bakeries to the poor quality of bread produced by privately owned bakeries, al-Watan newspaper reported.

Statements by regime officials were inconsistent with other statements made in early 2020, or with media activists’ reports, regarding the quality of bread produced by the state-run bakeries.

The regime’s officials repeatedly emphasized that the economic problems that have been burdening citizens have ended and are under control. However, economic researcher Khaled Tarkawi has a different reading of the situation.

Putting an end to the economic turmoil is not a priority for the regime. The case is just the opposite, the regime is deliberately creating these crises, Tarkawi said.

The ability to afford military supplies is all that matters to the Syrian regime when it comes to managing the country’s economy, not to mention that management is an “issue of governance,” used to prove it has control over the economy and the country despite these crises. Due to this, resolving the living crises is not the regime’s primary concern, according to Tarkawi.

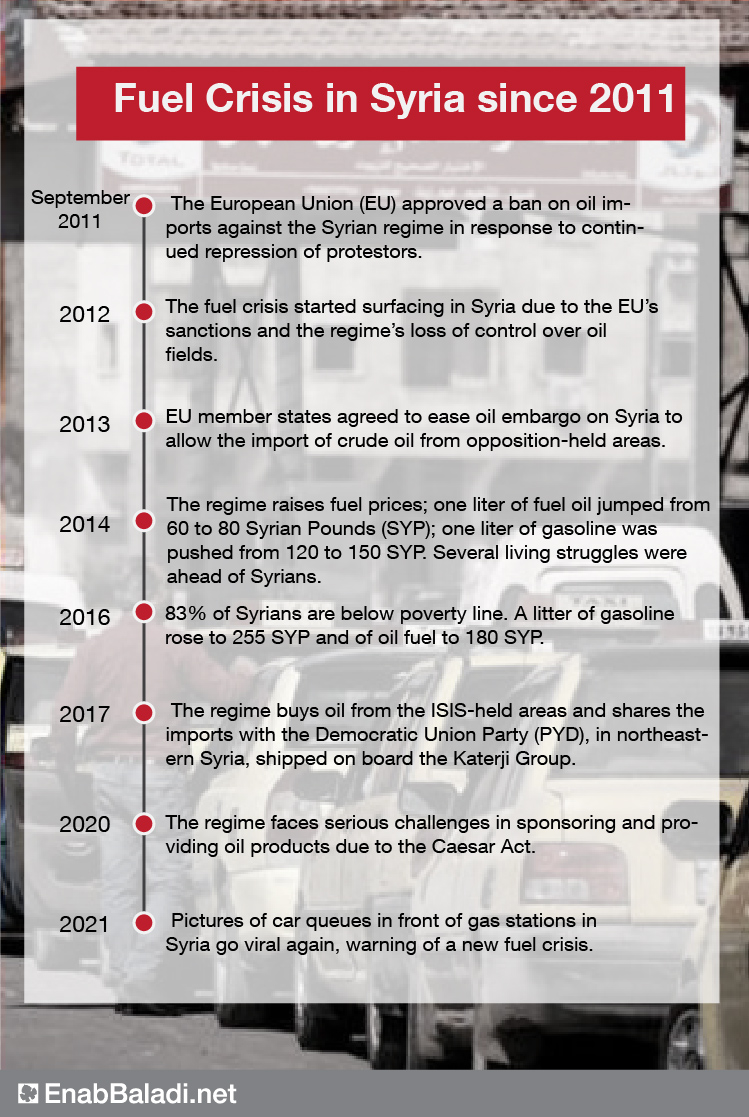

Did the fuel crisis actually end?

“The gasoline crisis has ended: starting today, over four million liters of gasoline and nearly six million liters of fuel oil for all provinces” is a headline that al-Watan newspaper published on 17 January 2021.

In this report, the pro-regime newspaper spoke of the regime’s work to address the gasoline crisis that became an issue again in the past few days, manifested in long lines of vehicles in front of gas stations.

“Serious technical and logistic challenges hamper the Ministry of Petroleum’s efforts to provide fuel,” al-Watan said in the same report, quoting an unnamed source.

To cover the demand, oil refineries need a monthly three million cubic meters of crude oil; these refineries have been provided with barely a million cubic meters, the newspaper added, stressing that since September 2020 only six million cubic meters of crude oil were obtained.

On 14 January, the Syrian petroleum ministry stated that additional quantities of gasoline and oil derivatives are being pumped to provinces after the Banias refinery was reoperated with the arrival of crude oil supplies.

Shortly after, the regime’s Ministry of Internal Trade raised the prices of subsidized gasoline—a liter of subsidized premium gasoline will be sold, starting from January 20, for 475 SYP to consumers, and a liter of “unsubsidized” gasoline for 675 pounds.

The Ministry of Internal Trade said that the ministries of finance and transportation are both responsible for the price hikes.

The increase is not related to the price, but it is intended as an amendment to the annual fee imposed on gasoline cars, director of the pricing department of the Ministry of Internal Trade, Ali Wanouss, said.

The annual fee of registering gasoline vehicles was increased from four to 29 SYP, as provided by the relevant article of Decree No. 75 of 2020.

The increase was announced an hour after the oil tanker of the Syrian Company for Oil Transport exploded near the Syrian Gas Company in Homs province. The explosion affected seven other oil tankers amidst the stifling fuel crisis in the regime-held areas.

Indicators that the fuel crisis will continue

Since the beginning of 2021, areas, where the regime predominates, have been suffering renewed fuel crises, which resemble several previous crises that struck these areas in 2020.

The fuel deadlock is the result of the regime’s failure to provide basic fuel allocations, necessary for the work of service sectors and for the population’s daily use.

On 10 January, Enab Baladi monitored the fuel distribution process. Long threads of cars spent days waiting in front and near gas stations in Aleppo city, northern Syria. This situation was threatening, as it is an indicator of a new fuel crisis in winter.

The fuel crisis that affected the regime-held areas is not a condition specific to 2021; it is rather the culmination of years of the regime’s inability to respond properly to the demands of the Syrian market of oil products since 2011.

There are political, economic, and military indicators to the fuel crisis which affect its intensity.

The first indicator of the spiraling fuel crisis is the curtailed allocations of fuel products. The regime’s Ministry of Petroleum and Mineral Resources said it has “temporarily” reduced the provinces’ shares of gasoline by 17%, and fuel oil by 24%. These cuts were the result of “the delayed delivery of contracted oil products’ imports. The cuts will continue till these supplies have arrived,” the ministry said.

The ministry attributed the said delays to the U.S. sanctions under the Caesar Syria Civilian Protection Act. However, the regime’s failure to overcome the fuel crisis is due to “lacking financial resources to pay for these products in cash,” which is the reason why the crisis has not abated, Muhammad al-Abdullah, an economic researcher at Omran Strategic Studies told Enab Baladi.

The regime cannot afford enough cash to pay contractors, Iranians, or the domestic networks of suppliers, “which made available oil products to ensure that the regime continues to rule,” al-Abdullah added.

The Syrian regime is coerced to find sustainable solutions for this crisis, because the situation in the regime-held areas has exacerbated, with all the indicators that the crisis is out of control and its effects which hampered the population’s life.

The regime is short on various oil products, most notably gasoline, a problem which officials hoped to solve by the end of the Banias refinery maintenance work in September 2020.

A second indicator that the fuel crisis will grow acute in 2021 is that the western sanctions on the regime continue to be effective, which have adversely affected the regime’s reserves of oil products over the course of the conflict.

Before 2011, the Syrian oil balance was tilting towards deficiency, despite exports. The imposed sanctions muddled the situation and the defect amounted to two or four billion per year, regardless of the major decrease in consumption.

The sanctions enforced by the European Union denied the regime any direct access to oil product imports. Directly or indirectly, the regime was unable to grant procurement credits or put cargo ships on insurance.

Consequently, the regime’s dependence on Moscow and Tehran increased, along with oil products’ trafficking from northeastern Syria.

In an attempt to circumvent sanctions, the regime will relay, whenever possible, on private sector businessmen and importers, to seal contracts of refined oil products, researcher al-Abdullah said.

These measures are all stopgap solutions, as they will control the crisis for a few months only. The regime will probably fail to provide sufficient amounts of oil products unless Iran decides to reactivate the line of credit to deter the collapse of its ally, researcher al-Abdullah added.

Iran used to export two million monthly oil barrels to Syria, which sometimes even amounted to three million barrels. In 2019, however, the Iranian credit line was disabled according to an agreement, which provisions, mechanism, or payment methods continue to be unknown. Since then, no Iranian oil tanker has arrived in Syria.

“Several of the regime’s business cronies have distanced themselves and stopped working to provide it with oil products,” this is the reason why the current fuel crisis is exploding, according to researcher al-Abdallah.

Another reason for this spiral is the growing Iran-Russia competition in Syria, for the two parties have been fighting to impose their own economic agendas on the regime to force it into scumming to their demands, the researcher added.

The third indicator that the crisis will continue is that the Islamic State has ramped up its attacks on the Katerji Company tanks, which provide the regime’s territories with crude oil.

On 5 January, the ISIS-affiliated Amag News Agency reported that “ISIS fighters have destroyed oil tankers and injured ten militants of a militia of the Syrian army. They were ambushed in the desert areas of Hama.”

Tankers of the company operated by the Syrian businessman Hussam Katerji transport oil from northeastern Syria to the regime-held areas.

Policies adopted by Syrian regime to get around economic crises

The regime’s policies; security methods; and economic administration have caused Syria massive losses in every domain. From having a diverse economy that produced the population’s basic needs, Syria became totally dependent on exports.

The regime’s military activities are the chief reason behind the destruction of infrastructure and depilation of the country’s resources, economic researcher Khaled Tarkawi said.

The regime has put the country’s resources in the service of its vast military machine, trying to regain control over the areas it lost. This created an imbalance in expenditures, most of which was dedicated to the military at the disadvantage of development. The regime is running a war economy.

The extent of damage can be observed in the internal trade sector, where it reached the highest levels amounting to 20% of the country’s overall loss by late 2019. These losses are caused by the multiplicity of authorities ruling the country and the economy of violence, manifested in checkpoints of all local parties to the Syrian conflict, including the regime and the armed opposition groups, according to a study by Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies.

Efforts to remedy the situation

The Syrian regime adopted stricter measures against any parties that deal in currencies other than the Syrian pound. Its punitive measures showed its security philosophy and manner in addressing the economic turmoil the country is enduring.

Offenders of these measures are susceptible to arrest and seven years in prison. A fine also was imposed, amounting to five million SYP according to Decrees No. 3 and No. 4, which are issued by the President of the Syrian regime, Bashar al-Assad.

Under the provisions of Decree No. 3 of early 2020, persons dealing in currencies other than the Syrian Pound will be fined and sentenced to temporary hard labor for seven years at least. The fine is worth the amounts paid; used; the value of the service provided, or commodities offered by the involved persons. Additionally, precious metals; sums paid; or used will be confiscated to the benefit of the Central Bank of Syria.

Under Decree No 4, offenders are fined and subjected to temporary detention. Offenders pay a fine of between one and four million SYP. Offenders include “those who spread fabricated information, fake allegations, or lies in any mean to destabilize or effect a decline in the value of the national currency or its exchange rates determined in the official gazette, or undermine trust in the state’s solid finances or its monetary instruments.”

Such decrees demonstrate the Central Bank of Syria’s inability to deploy the tools of monetary policy, including intervening through pumping dollars into the markets and raising the benefit bar, to control inflation and protect the Syrian pound.

Despite the regime’s heightened measures, the Syrian pound continued to collapse, as reported by a study conducted by Omran Strategic Studies.

The tightened security grip over exchange companies and offices was all in the regime’s favor, for the foreign currency resources that these companies represented were all at the disposal of the concerned authorities. This was the primary aim of the decrees mentioned above.

As for the prices of basic materials and commodities, they are linked to the turbulence in the dollar exchange rate and inflation. The regime was not intending, as a priority, to encourage providing these commodities, but, on the contrary, to monopolize these commodities through the Syrian Trading Company (STC), which is the main distributor of these goods, according to researcher Khaled Tarkawi.

To overcome economic emergencies, the regime attempted to summon Russia and Iran to its help. But these countries have their own interests to look after and are not “charities.” They take from the regime what befits them, and the regime, today, no longer has anything to give, so this attempt to seek shelter in these countries was not as effective as in earlier times, researcher Tarkawi said.

Any way out?

Political stability is essential to overcoming crises, in addition to security stability. Both constitute the foundation for restructuring the Syrian economy; setting development and recovery going; and making any economic steps on an accumulative development path.

Accordingly, any radical solution must be hinged on a political solution and an agreement between all parties to the conflict to start the process of development and invest its outcomes in the Syrian economy. Any other solution would be only temporary and difficult to apply, researcher Tarkawi said.

A study by the Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies outlined three scenarios as awaiting the Syrian economy after the collapse of the Syrian pound in 2020.

The first scenario is that the regime will respond to pressure, showing a little flexibility in relation to the political solution and the detainees and kidnapped issue, which are prerequisites to ease the sanctions the U.S. has imposed under the Caesar Syria Civilian Protection Act.

The second scenario is that the regime will adopt the “resilience policy,” including the reduction of production costs to encourage growth within the agriculture sector and increase crops; jumpstart production lines in several industrial domains to meet the local market’s needs; and stop the import of a range of materials.

The third scenario is that the regime will persist to be “intransigent,” basically continuing with its oppressive methods and security-based doctrine in addressing political and economic issues, while blaming its failure on the Caesar Act and other international sanctions.

if you think the article contain wrong information or you have additional details Send Correction

النسخة العربية من المقال

-

Follow us :

Syrian 2000-pound bill and U.S. 100-dollar bill— designed by Enab Baladi

Syrian 2000-pound bill and U.S. 100-dollar bill— designed by Enab Baladi

A

A

A

A

A

A

More In-Depth

More In-Depth