Hiba Shehada – Yousef Ghuraibi

A man in his fifties walks the streets of his city in the northeastern countryside of Idlib. He points at buildings that invaded the streets or blocked the sunlight from other buildings. “There are several sponsors for urban planning, but none of them is acting,” says engineer Abdulhakim al-Asaad to Enab Baladi, talking about infringements that went beyond visual distortion to threatening people’s security and the future of their town.

The term “master planning” refers to a future vision of urban development in a community, taking into consideration both the population density and the residential space. The last time Idlib underwent urban planning was in 2005, and this process should be reevaluated and repeated every 20 years. However, the Syrian government’s final regulatory plan failed to predict the future of the governorate in which the population doubled, spaces narrowed, and supervision became non-existent after the unforeseen Syrian revolution.

After several years of conflict over power in the last stronghold of opposition factions and entities in Idlib, the responsibility for urban development supervision shifted among parties that did not prioritize urban planning as much as expanding their power. Thus, this has resulted in irregular residential areas in Idlib with infrastructure and services unable to meet the needs of even a quarter of the population.

What is the current status of the region’s master plans? What impact their flaws have on people’s lives? Who is responsible? In this file, Enab Baladi addresses these questions by meeting engineers and officials in Idlib in search of possible solutions.

Planning the future while neglecting the present

Abdulhakim al-Asaad is an engineer who lives in Binnish city in the northeastern Idlib countryside. He has worked in local administration and infrastructure services for more than 30 years in Syrian state institutions.

Al-Asaad reviewed the master plans, which he kept on his laptop while enthusiastically talking about property laws and regulations that shaped the city maps of Idlib 15 years ago. “The foundations of urban planning are divided into two parts. The first is based on technical engineering standards concerned with securing the community’s societal and humanitarian needs. Meanwhile, the second part consists of the standards and principles relevant to how the regulatory plan is formulated and prepared, and how it is approved and managed by creating the urban planning program,” al-Asaad says.

According to al-Asaad, master planning is concerned with setting urban boundaries of a population center such as agricultural, residential, and health services facilities to meet each individual’s needs within his/her place of residence, work, and education. This includes the basic services in the present and the future, including workplaces, shopping centers, parks, places of worship and schools, infrastructure services such as sewage networks and roads.

The last urban planning in Syria took place in 2005. It defined the services and laws governing urban development according to a vision intended for more than 20 years. However, the planning, which predicted an increase in population number from 1.2 million to 1.7 million in 2020, according to a growth rate of 2.4 percent, did not anticipate the displacement waves and the war years that have afflicted the popular movement demanding reform since 2011, which doubled the population of the governorate and shrunk its area.

The organized streets and buildings in the city of Idlib- 03 September 2020 (Enab Baladi / Yousef Ghuraibi)

Map of land loss in Idlib

“Dangerous” violations and infringements

Urban planning guarantees people’s safety and stability in cities. Urban allocation necessitates the licensing of the established buildings and guarantees safety standards for residents along with appropriate services, according to civil engineer Abdulhakim al-Asaad.

Nevertheless, infringements in shops, markets, housing blocks, residential villages, and camps are widespread in the region since displacement began in 2013, according to engineer Saria Bitar, who runs the “This Is My Volunteer life” group in Idlib.

“When a camp is established, displaced people start coming in for housing. Over time, tents become housing units that expand to meet the needs of the displaced families. Then shops are opened, so people make a living, which leads to chaos and informal slums represented in markets and dwellings in unsuitable locations,” says Bitar to Enab Baladi.

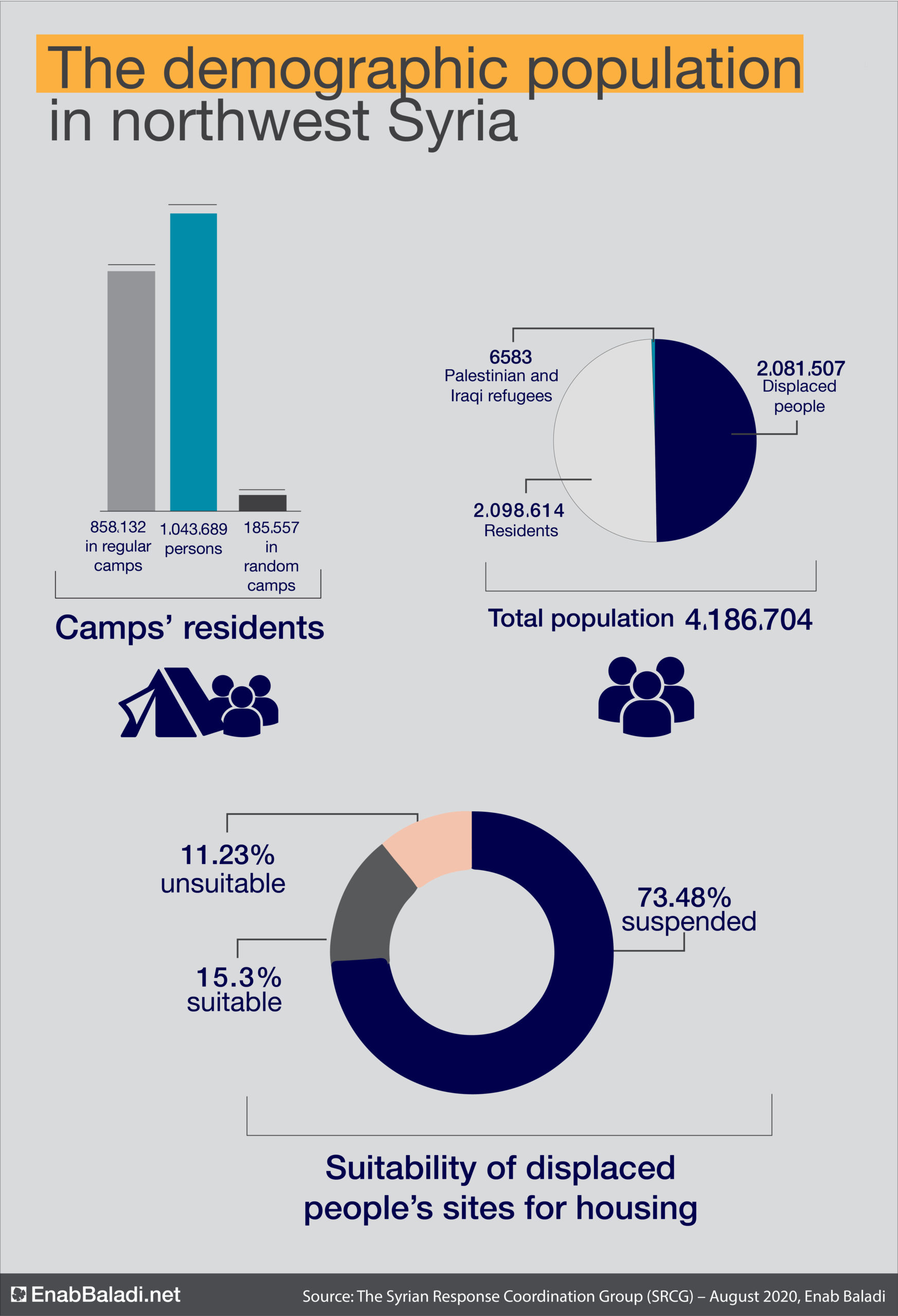

There are more than a thousand regular and informal camps throughout the governorate. They are inhabited by more than 1.2 million people in unsuitable locations with inadequate services. These people’s needs have increased the burden on neighboring villages, towns, and cities, which are already crowded with displaced people, leading the majority to depend on humanitarian aid due to the lack of various health and support services.

The population growth rate in some areas exceeded by tenfold. Bitar mentioned Qah village as an example, saying that the infrastructure there was made to serve 4000 residents; however, the population now is between 40 and 50 thousand. The area suffers from problems with its sanitation and waste disposal. “If the regulatory plan of Qah is not updated, there will be a problem. We are facing problems now with the increasing population, and these problems will continue in the future.” Bitar said.

Was urban planning ever right to begin with?

In 2005, the international expert in urban planning law, Patrick McAuslan, completed his mission in Syria, which lasted from August to September of the same year. The mission aimed to assess Syria’s urban plans with the European Union’s help. McAuslan wrote regarding the evaluation of Syria’s urban plans in his report in cooperation with Engineer Hussam Safadi that the urban planning in Syria is “good” in terms of the legal framework which takes into account the rights of landowners, but “weak” as it “prevents development.” The plans also included “complex” regulations that impeded legal work and “encouraged random housing.”

The original organization plan of Idlib city was made in the 1960s, with additions of new areas being made every decade or two, according to al-Asaad. Idlib city’s area was 200 hectares (2,000,000 square meters m2) in 1960 and increased to 650 Hectares (6,500,000 m2 ) in 1972. At that time, the total area of Idlib province was 2,000 hectares (20,000,000 m2 ) of regulated and allocated land. The regulated areas expanded to 13,500 hectares (135,000,000 m2) in 1995, until it reached 18,600 hectares (186,000,000 m2) in 2005, and included all cities, towns, villages, and small gatherings of no more than 2,500 people. This was achieved by defining primary and secondary streets and even corridors, alleys, architectural style, sewage networks, etc.

The government introduced a set of laws governing local communities and mandated municipalities and governorates to ensure their implementation to preserve the urban plan, including Law No. 9 of 1974 on the division and organization of urban development, Legislative Decree No. 5 of 1982, the Urban Planning Law, and Legislative Decree No. 20 of 1983, regarding expropriation.

This was followed by Law No. 1 of 2003, which includes dealing with building violations, Legislative Decree No. 59 of 2008, for removing violating buildings and building violations, Legislative Decree No. 107 of 2011 for the local administration, Legislative Decree No. 20 Of 2012 regarding building violations, and Law No. 23 of 2015 regarding the implementation of urban planning and construction.

“As a result of the Syrian regime’s loss of control on vast areas, state institutions became absent and local councils became inefficient,” as described by al-Asaad. “They were unable to protect the master urban plan, which caused many violations and infringement on urban structure,” he said.

According to McAuslan’s assessment, the Syrian property laws before 2005 were “inconsistent,” and the laws governing urban planning were concerned with the physical development of the planned area only, neglecting the social, economic, and environmental aspects of the development. These laws ignored people’s voices who own the future of their city in the first place. There was no place for non-scientific and personal points of view regarding the future of the area.

McAuslan believes that the Syrian regulations are based on a sense of “optimism and self-confidence” because they trust landowners and the private sector to develop the urban plan according to the vision set for it, despite the limits on the development process posed by the details of the very same regulations. This renders the new plans outdated as they take a long time to be prepared.

Regardless of whether the preset plans are adhered to or not, the old main regulatory planning will lead to unauthorized random development due to the rapid urban development and the increasing population, which necessitates meeting the needs of people, jobs, and infrastructure at larger numbers and speed.

The speed of the increase in the population has doubled during the war years. Waves of displaced people reached Idlib in a short period causing random urban development. The authorities turned a blind eye to this without any intervention or organization, contenting themselves with counting and following up the problems resulting from congestion and lack of services.

The Engineers Union’s building in Idlib, which the Syrian Salvation Government (SSG) took control of in October 2020 – 3 September 2020 (Enab Baladi / Yousef Ghuraibi)

Mutual accusations and responsibility that no one espouses

Several parties controlled Idlib successively. In 2015, opposition factions were able to control all of its areas. The Syrian Interim Government (SIG) of the National Coalition for Syrian Revolution and Opposition Forces, commonly known as the Syrian National Coalition (SNC), tried to run the institutions that belonged to the Syrian state. In 2017, the Syrian Salvation Government (SSG) was formed under the Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) and worked on taking control of the entire province and achieved that after a year and a half.

In an article titled “HTS”…establishing itself or drawing its last breath”, Enab Baladi discussed the economic gains of the battles for control and imposition of power. However, these gains did not result in providing better services or better urban organization. Random urbanization did not stop despite the issuance of decisions related to local administration and even urban planning.

For building or expansion of construction, an individual should go to a local council with the necessary documents proving his ownership of the plot of land he/she wishes to build on. Such documents include a title deed or a real estate registry statement, and cadastral survey plans for the land, after which the council determines the location of the land in the area included in the regulatory plan and the building scheme that regulates the area and construction conditions for establishing a structurally safe building.

After that, the landowner submits the construction plans to the council. The latter examines the plans in cooperation with the Engineers Union, which al-Asaad described as the “partner who sponsors the development of the urban master plan.” The engineer is the one responsible for the development of the building in urban terms, as well as carrying out the structural, architectural electrical study, and all that is necessary for building according to the rules and explanations of the local council.

However, the relationship between the Engineers Union and the SSG was not cooperative in implementing or maintaining Idlib’s regulatory plans.

On 30 September, the SSG called on engineers in the region to form a union, ignoring the already existing active union since 2018 that has brought together more than 600 engineers. A member of that union, who prefers to remain anonymous for security reasons, told Enab Baladi that the SSG had disabled the union’s role in studying and approving regulatory plans and overseeing its construction a year ago.

The SSG refused to cooperate in an attempt to interfere with the union’s work and take it under its control. This contradicts the independent civil nature of unions. “The SSG’s aim was obtaining the proceeds of study, auditing and supervision,” according to the union member. He also referred to the SSG’s decisions to transfer building plans to municipalities without being approved by professional engineers.

The SSG controlled the Engineers Union’s building through a “security” task force with masked members. They asked the people in the building to leave and held “fake” elections, as the member said. In the elections, all of the “preparatory committee” members were nominated, described as “illegal” by the union member.

The SSG ignored Enab Baladi’s inquiries about the dispute with the Engineers Union, contenting with denying its accusation of refusing to cooperate. In return, it accused those in the union of adhering to their “personal interests,” according to the director of media relations, Molham al-Ahmed, who told Enab Baladi in a previous interview that the establishment of the new union was “at the request of a large number of engineers.”

What is the role of the “Salvation Government” in Idlib?

Engineer Mustafa Sattouf, who is in charge of running the SSG’s technical services affairs, reviewed the regulatory plans that were kept by the Technical Services Directorate of the regime’s government in Idlib and told Enab Baladi that the waves of displacement prompted the amendment of these plans.

“Each wave of displacement was accompanied by new reviews to the plans, according to the population distribution and priorities,” Sattouf added. He pointed out that the SSG formed regional committees to study some villages’ urban plans, such as Darkoush and Taftanaz, and to adjust some housing characteristics in the buildings to accommodate the increase in population.

The most recent of those committees announced by the SSG was the regional committee for Sarmada and al-Dana towns. These towns are witnessing severe overcrowding due to their proximity to the Turkish border, which is deemed safer. Sattouf indicated that the committee’s mission is to conduct a detailed technical survey of all violations, address them, and make the appropriate decision.

However, Enab Baladi tried to contact the aforementioned regional committee, but in vain, until a delayed response came saying that the committee was suspended less than two months after its establishment.

The SSG issued a set of laws on urbanization, which Sattouf described as “controlling the urban process in a good and excellent way,” but he did not deny the informal settlements by the region’s military campaigns. The last of such settlements was nine months ago.

Data on the distribution of displaced people in residential buildings and camps

Through a series program named “What is your problem?”, Enab Baladi monitored the issues of random construction in violation of regulatory plans, infrastructure problems, lack of rehabilitation of roads and sanitation, as well as problems of setting up camps on private lands without support and organization. Enab Baladi also shed light in its property rights investigations in Syria on the future of the uncontrolled spread of informal camps, and the SSG responded by talking about future plans that were not executed on the ground.

In a previous interview, the former head of the Engineers Union in Idlib, Imad Shaaban, told Enab Baladi that adherence to regulatory plans and controlling random construction was only done in the city of Idlib. However, with the role of the union being disrupted by the administrative authorities, engineers could not scientifically supervise the construction nor oversee the plans and the correctness of the implementation.

In Idlib, the “control and executive authority” control the construction process, said Shaaban. He pointed out that the negligence of laws is due to city councils’ lack of commitment to applying and implementing urban plans in rural areas. The reason behind that is the weakness of the executive authority and overlooking violations.

The former head of the Engineers Union added that the urban organization plan needs to be continuously expanded and edited to correct mistakes and reorganize through the formation of regional committees, but those committees are also “disabled.”

Monitoring and controlling violations… awaiting complaints

Architectural irregularities arise and continuously expand as a result of the needs generated by the continuous population increase, the lack of awareness of the importance of proper technical and structural studies to ensure the safety of the established buildings, and the impact of its randomness on the future of the city and the distribution of necessary services to residents.

However, the competent committees’ lack of oversight to detect infringements and violations makes the process of correcting violations subject to citizens’ complaints when they are affected by urban planning.

Architect Talal Aswad, a consultant in construction lawsuits, provides consultancy when requested by the judiciary. Aswad noted that violations often arise as a result of lack of supervision by specialized engineers or the engineers’ failure to participate in the construction process from the ground up.

“There are human souls in these buildings; besides, they cost a lot of money. When a building lacks regulatory planning, technical and administrative control, this results in architectural deformation and backwardness rather than progress in the country,” said Aswad to Enab Baladi, indicating that the judicial follow-up for violations is limited to citizens’ complaints.

Regarding the city of Idlib, the control is estimated at a rate of 95 percent, while the violation percentage is “very large” in other areas of the province.

How can the problems be solved?

According to architect Saria Bitar, urban planning problems can be solved when local institutions work in a more practical rather than theoretical manner. Bitar told Enab Baladi that controlling the construction violations needs to start immediately to alleviate future problems.

Bitar suggested forming patrols to monitor the construction of residential or commercial buildings, detect construction violations, direct displaced people to well-studied places of residence and protect them from falling into the problems of housing irregularities or being exposed to seasonal floods as a result of choosing the wrong places to live in. He also called on setting a future study of suitable housing places for emerging population groups.

Bitar gave an example of the service problems caused by construction and urban organization irregularities, as in the roads of Atma and Deir Ballut. There, the residents’ overstepping their designated areas led to the wrecking of the sewage system and damage to the asphalt in the roads. Consequently, passing vehicles were damaged. The adverse effects caused a chain reaction of further issues.

Ignoring urban development problems will lead to “disasters” because displacement movements are increasing and the irregular constructions and service problems, according to the Idlib office director of the “This Is My Volunteer Life” group.

The biggest problems that the residents and local authorities will face is the financial cost of removing violations and regulating housing. Bitar referred to what happened when the Bab al-Hawa Crossing’s administration tried to expand its roads. The administration had to foot the bill of the violators to clear their locations. “If they had started with clear urban master plans, they would have saved time, effort, and money,” Bitar said.

According to Bitar’s assessment, the responsibility for the urban violations occurring today rests with the municipalities, local councils, and the Engineers Union because cooperation among these parties to supervise the plans and control for regulatory violations is the way to control urbanization.

Some construction violations are affecting social landmarks or streets. According to Engineer al-Asaad, these violations can only be removed by demolition. He pointed out that technical principles and urban reality depend on engineers’ work and their participation in planning, evaluation, construction, and solving the problems.

As described by al-Asaad, the relationship between the union and local councils was fluctuating according to the reality of the society and what it has gone through after the absence of state authorities’ role since 2011. People sometimes start building without referring to local councils or specialized engineers, causing the administrative councils to transfer to “aid distributing committees,” marginalizing the engineers and the local councils.

According to al-Asaad, the current defect in the regulatory plan is because the current authority has abandoned it, which led to a decrease in awareness of its societal importance and the disruption of the role of the local councils responsible for dealing with it.

McAuslan wrote in his report that the adaptation of the urban plan to the increase in population and its modification to be suitable in the future is based on five principles, to be “equitable and socially responsive,” through the ease of legal processes related to acquisition and construction, and to be “resilient” because rigor causes failure in this case.

Moreover, adopting a “positive” approach encourages development by reducing licensing requirements, as not all modifications require licenses, and reducing the information required when filling out licensing forms to achieve the required conditions.

Finally, the urban plan must be “environmentally-conscious” to optimize the utilization of natural resources with the increase in population to avoid pollution and meet people’s needs. It should also be “efficient” so that its cost is not high with its association with reasonable benefits obtained through control and management.

Despite the obstacles brought by property laws in the Syrian case, they remain the “starting point,” McAuslan wrote. This is only possible when legal provisions push for development instead of reintroducing old initiatives and plans under new names, according to McAuslan.

A destroyed building as a result of the bombing in the city of Ariha in the southern countryside of Idlib – 23 September 2020 (Enab Baladi / Yousef Ghuraibi)

if you think the article contain wrong information or you have additional details Send Correction

النسخة العربية من المقال

-

Follow us :

Ariha city in the southern countryside of Idlib - 23 September 2020 (Enab Baladi / Yousef Ghuraibi)

Ariha city in the southern countryside of Idlib - 23 September 2020 (Enab Baladi / Yousef Ghuraibi)

A

A

A

A

A

A

More In-Depth

More In-Depth