Enab Baladi’s Investigation Team| Murad Abdul Jalil | Haba Shehadeh | Taim al-Haj

“There is only one society in Syria, and it cannot be divided into civil and non-civil society. There is one society; a civilized civil society.” This is the approach that Bashar al-Assad disclosed in the third year of his rule of Syria, and he continued to implement it till late in his “legitimacy” years.

16 years after al-Assad’s famous statement, the Syrian society has become divided into three sections at the negotiating table to draft a new constitution, between the regime, the opposition and a civil society that is trying to play a role, presumed to be a mediator or consensual.

Recently, with the start of the work of the Constitutional Committee in Geneva, under UN auspices, questions about the role that civil society could play at the political level started arising. Between rejectionists, supporters and apprehensive views, the civil society list within the Committee is still trying to define its true role, reduce its division and direct its compass towards one single goal.

In this file, Enab Baladi sheds light on the role of civil society in the constitutional process, the reasons behind its division and attempts to politicize it, and seeks to assess the chances of the continuation of the civil society and its future within the political process.

In the testing process of the Constitutional Committee

Differences in positions spoil the civil society’s influence

In 2016, former international envoy to Syria, Staffan de Mistura, announced the establishment of a Civil Society Support Room, known simply as CSSR in Geneva, which is a stage that could be considered a turning point in the work of the civil society.

With its organizations, unions and councils, the civil society was not far from politics, but entered it indirectly via the international community, and then directly through participation alongside the opposition and the Syrian regime with a third list in the Constitutional Committee tasked with the drafting of a new constitution for Syria.

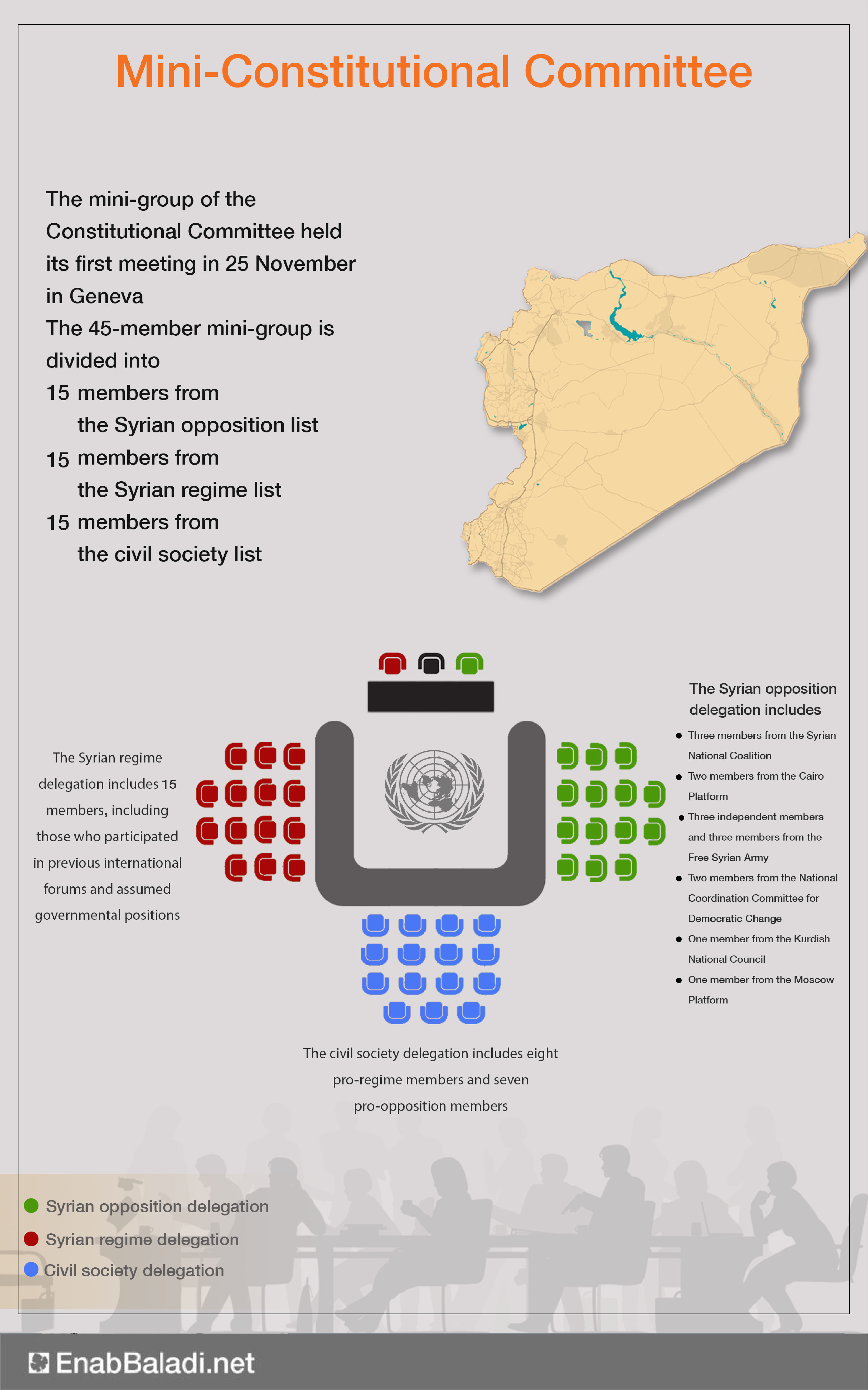

| The basic layout of the Constitutional Committee was announced at the Sochi Conference that was held in Russia under the name of the Syrian National Dialogue Conference, on January 30, 2018, to consist of three lists, the regime, the opposition and the civil society, each of which has 50 members. A mini-committee, consisting of 45 members, with 15 names from each list, had then emerged from the Constitutional Committee to formulate the provisions of the constitution. |

The civil society’s involvement into the political conflict has stirred the reservations of many parties, including the CEO of Bercav Organization, Farouk Haji Mustafa, who insisted that the civil society has played a minimal and biased role, and this has negatively affected it.

The civil society is presumed to be concerned with the public interest, according to Haji Mustafa, who expressed his concerns over falling into conflict and political polemics. He also pointed out that the civil society should play the role of mediator, and provide consensual compromises between the two politically-conflicting parties rather than being biased to any party.

The beginning of division

With the first moments of the start of the first rounds of the Constitutional Committee’s work with its full members, on October 30, the division and differences between members of the civil society has become evident in terms of opinions and political and even legal positions.

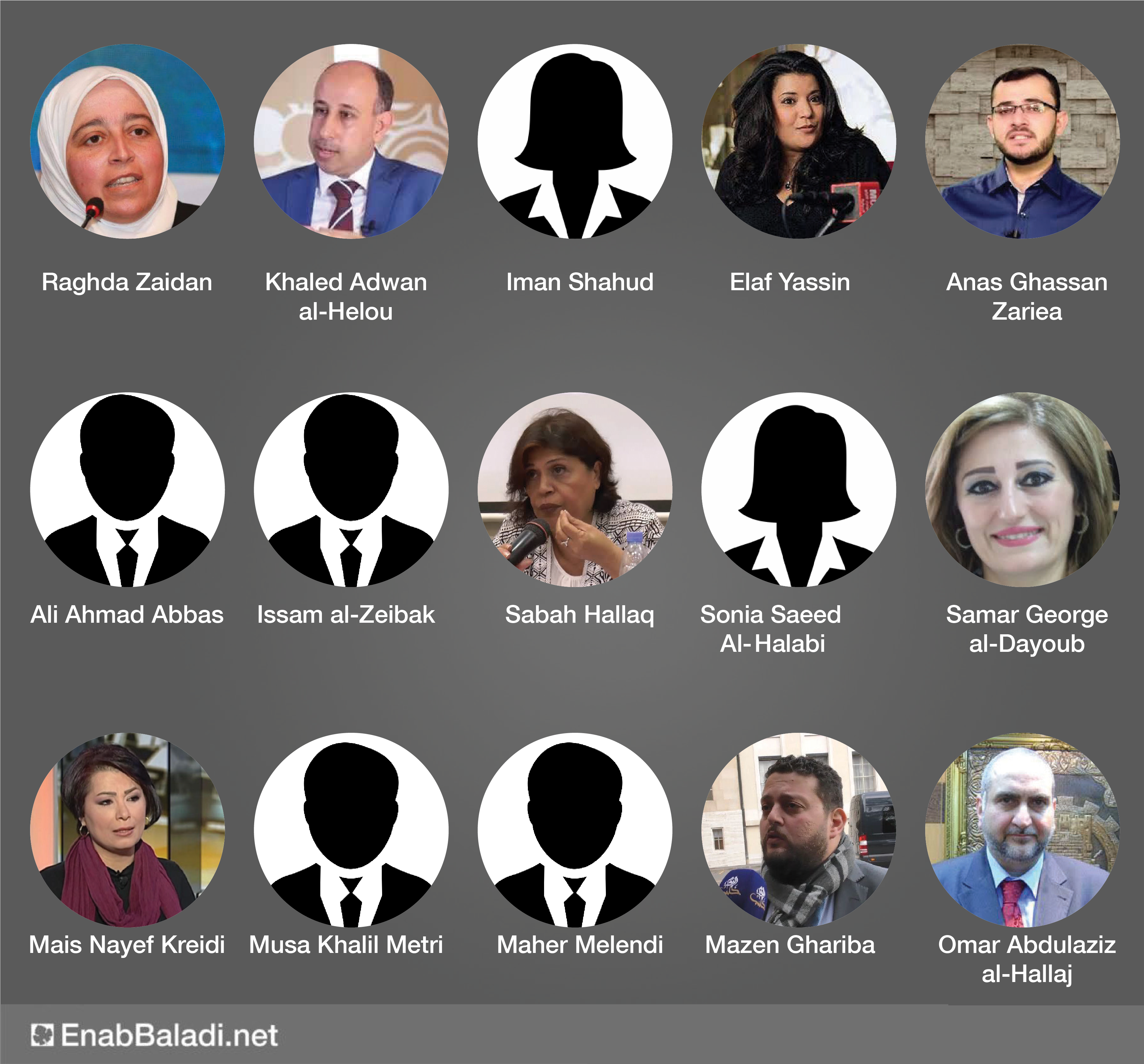

The civil society list includes 50 names, some of whom are biased to the Syrian regime, and reside in Damascus, while another part of it include members with anti-regime orientation. The civil society is also represented in the mini-committee emanating from the Constitutional Committee by 15 members, divided into eight members supporting the regime’s point of view, and seven supporting the opposition’s point of view.

During the first two rounds of the Constitutional Committee’s meetings, pro-regime members focused on “condemning the terrorist groups’ attacks in Aleppo, and denouncing the economic sanctions imposed on Syria,” while the pro-opposition members stressed on the need “to work for the immediate release of all prisoners of conscience by all the parties in Syria, reveal the fate of the forcibly disappeared people and form a national committee to periodically monitor the release of detainees by all sides according to a specific timetable.”

However, the clear and real division in the civil society has appeared in the second round of the mini-committee’s meetings, when the media discourse escalated between the two parties, and reciprocal accusations of dependency started, especially by members coming from regime-controlled areas, who accused the other delegation (the seven-member group) of implementing agendas of other countries, especially Turkey.

To find out the reasons for the division and differences between members of civil society, Enab Baladi, which followed up the work of the second round in Geneva, met some members of the two delegations.

Division reinforced by dependency

A member of the delegation of the mini-constitutional committee emanating from the civil society delegation, Sabah Hallaq, expressed her regret over the division and differences in the civil society list. She also stressed that the delegation of the pro-regime eight-member group announced frankly at the first meeting that it was supported by the “Syrian government” knowing that, according to the concept of civil society, it must be an observer and a monitor of the government’s work, not supported by it.

As for the seven-member group, it may be considered as an opposition group, but its members are independent and not affiliated to political bodies such as the Syrian High Negotiations Committee (HNC), while the other side accused them of being affiliated to the HNC.

The member of the mini-constitutional committee emanating from the civil society list, Raghda Zaidan, also confirmed that the members of the delegation from Damascus spoke openly about their Damascus reference, and that they are not a civil society. On the other hand, the other delegation, asked through a clear letter sent to the international envoy, Geir Pedersen, not to be treated as belonging to the Syrian opposition, and they asserted that they represent all Syrians.

Zaidan pointed out that the “seven members” in the mini list asked the delegation from Damascus to work together to present a joint paper in the name of civil society, but they withdrew from the meeting and refused to work, prompting six members of the civil society to present their own paper on the constitutional contents.

A general view during the meeting of the Syrian Constitutional Committee at the United Nations headquarters in Geneva, Switzerland October 31, 2019. Martial Trezzini/Pool via REUTERS – RC1A1AD4CDA0

Political polemics

During the second round of the Constitutional Committee meeting, the civil society delegation turned from playing a mediating and calming role between the two parties of the conflict to engaging in political polemics and reciprocal political accusations, through the media.

The member of the mini-constitutional committee emanating from the civil society delegation, Mais Kreidi, who is one of the members of the eight-member group, attributed the reason for this to the fact that the conflict inside the Committee is political. This is in addition to the existence of political assumptions and an attempt to politicize civil society with the will of Pedersen, or with stronger wills than him through countries that can influence and dominate the United Nations. She also asserted: “We must respond politically and present our concerns.”

“There are people in the civil society list who are more rigid than the Riyadh delegation (referring to the Syrian opposition delegation). This drives us (coming from Damascus) to respond politically, because one then will face his direct personal convictions,” Kreidi told Enab Baladi.

She added that “civil society is not neutral and was chosen on the basis of certain balances.” Kreidi considered that the opposition delegation within the list of civil society “is not dynamic at all about engagement, as they want to increase political condemnations of the Syrian state and have media gains.”

Kreidi accused the members of the other group of civil society (the seven-member group) of being not independent and adopting the viewpoint and projects of the countries sponsoring them, saying, “We are being thrown into political discussions inside the group. When political discussions take place, we will certainly not accept to be overlooked, if indeed the goal is building a person and a human mind; we will all cooperate.”

Kreidi held on to what she considered a “patriotic” perspective position, saying: “When you have a passport of another country, you are bound by its rules, and in this context, this is how they want us to carry out a deceptive operation against the Syrian people and adopt suggestions that have no effect on the Syrian people searching for their livelihood and safety?”

However, the member of the mini-constitutional committee emanating from the civil society list, Raghda Zaidan, denied the accusations, and stressed that the civil society delegation discussed issues related to the rights of people, and presented a “no paper” on the necessity of releasing detainees and forcibly disappeared people, without deviating from constitutional principles.

Zaidan clarified that all the interventions during the meetings of the first round were focused on people’s concerns and demanding their rights, property rights, compensation for harm, transitional justice, holding criminals accountable, and releasing detainees, while refusing to discuss political issues that the regime delegation wanted to discuss, such as terrorism and condemning the intervention of Turkey and other countries.

According to Zaidan, members of civil society opposing to the regime’s viewpoint put forward a list of 225 constitutional ideas and asked to discuss them by the Committee. However, the “delegation coming from Damascus” responded to that by repeating the same words of combating terrorism, the heroism of the army and demanding condemnation of the Turkish intervention. “Are talking about the citizens’ concerns, demanding to release the detainees, calling for justice and securing the return of the IDPs and emigrated persons part of politics?” wondered Zaidan.

She considered that the regime’s delegation and those supporting it in the civil society group came with clear orders to just hinder the Committee’s work, and they refused to discuss any constitutional content.

As for the member of the mini-constitutional committee emanating from the civil society delegation, Sabah Hallaq, she confirmed that the files presented in the “no paper” regarding detainees and missing persons were put forward to be discussed by all parties and not only the regime, as they are part of an unnegotiable humanitarian file, and is supposed to be resolved because it paves the way for the political process and confidence-building.

Politicized committee?

Amid the accusations among the members of the delegation, Yamen Ballan, a member of Hamzat Wasl association, considers that the civil society delegation is essentially politicized from the very first moment of its formation, and division has existed since the establishment of the Civil Society Chamber in 2016. This is because a part of it believes that the United Nations is able to communicate its voice and achieve an impact, while another part believes that the UN process is only aimed at undermining the civil society’s role and cause, turning it into an ineffective side.

This has been evident in the second round of meetings, as the civil society delegation has not played any role in bringing the views of the opposition and the regime closer. According to what Enab Baladi monitored during its follow-up of the meeting session in Geneva, the list of civil society was not consulted in the meetings’ agenda and the work schedules, and discussions at the time were limited between Pedersen and the Committee’s Joint Heads: Hadi al-Bahra, on behalf of the opposition delegation, and Ahmad al-Kuzbari, on behalf of the delegation of the regime.

Ballan indicated that there is one civil society that considers Syria as a single geographical area, and another civil society affiliated to the regime in one way or another and executing its agenda. There is also another part affiliated to the opposition or against the regime and implementing a political agenda. This is in addition to civil society in the Kurdish region divided into two parts: one serving the Autonomous Administration and its project, and a real part considering Kurdish Arabs together.

How were the names of the civil society list chosen?

The United Nations played a major role in drawing up the first list of the civil society delegation in the Constitutional Committee, according to a study by the London School of Economics (LSE), published in October. The first list was varied and composed of members of civil society and legal as well as constitutional experts from various backgrounds, most of whom were independents.

The list was also “lengthy” and formed through nominations submitted by the countries concerned with the Syrian file, with the opposition and the regime, stated a well-informed source about the selection mechanism, speaking on condition of anonymity, to Enab Baladi.

With the continuation of the selection process, it turned into “dictation” by the guarantor countries, Turkey, Russia and Iran, which used the veto right for a certain number of names, leading to major concessions that affected the credibility of the civil society delegation, especially after the rejection of important Kurdish personalities. This in turn led to the removal and replacement of dozens of names from the list to satisfy several parties.

Although “important” personalities remained in the final list, according to the British study, “independence from external and political parties” was lost due to the interference. With a lack of transparency, this process has also undermined the credibility of some of the most important figures in the list, who became suspected as they were not rejected like the other figures, according to the source.

After talks and negotiations on the civil society list, the United Nations chose 20 names, which neither the regime nor the opposition objected, according to the source, while Russia imposed names that were added to the Syrian regime’s share of the list, and the United Nations imposed names on the share of the opposition and the regime.

The list is currently divided into 27 names chosen by the Syrian regime and 20 names approved by the opposition, with three names imposed by the United Nations. As for the mini list, the regime chose eight names, the opposition approved five names, and the United Nations imposed two names.

The Committee is a civil society trap

The CEO of Bercav Organization, Farouk Haji Mustafa, believes that civil society has fallen into the “trap” of the Constitutional Committee, in an attempt to marginalize it. This is due to the names selection mechanism, and “especially on the part of the Syrian regime, which has chosen personalities unrelated to civil society, but rather most of them are members of the leadership of the Baath Party division, party branches, or institutions affiliated with the regime.”

For his part, Yamen Ballan, a member of the Hamzat Wasl civil organization in northeastern Syria, has reservations on the selection mechanism of names of the civil society list and his participation in the constitutional process, because “civil society does not give up, nor negotiate (politically) and it represents all Syrians and the rights of citizens.” Ballan expressed his dissatisfaction with the transformation of civil society into an affiliated party to office of the UN envoy, who refuses to invite anyone to the civil society room meetings or rejects objecting to anything related to the UN process, arguing that it disrupts consensus.

Ballan told Enab Baladi that the warring and conflicting parties, whether they are political or military parties, and supportive countries behind them, need to legitimize any agreement between them, and legitimacy comes from civil society as it represents all citizens.

Ballan added that the Syrian parties are not independent and directed by external parties, whether the regime, the opposition or Autonomous Administration in the eastern region. He pointed out that he hoped that civil society would be able to be independent, play the role of a monitor and be the voice of the people. However, with time, it transformed from a struggling civil society to a professional civil society, only looking for projects and funds.

Turkish veto on Kurdish representation

For his part, the CEO of Bercav Organization, Farouk Haji Mustafa, blamed guarantor countries for the choice of names in the first place, since Syrians were aware of the names participating in the Committee through them. He also blamed the opposition and the Syrian regime, which both accepted the reality and the imposition of the names.

Haji Mustafa also blamed the civil society participants who thought that the Constitutional Committee might be one of the reasons leading to another stage. However, they fell into the trap of the guarantor countries, as the two poles (the opposition and the regime), supported by the regional countries, headed towards achieving a political deal and a specific settlement towards drafting a constitution, especially since there are people with expertise who were not included in the mini–committee, because of their refusal to be affiliated to any party, whether the opposition or the regime.

In addition, the weak representation of the Kurds in the constitutional process raised the discontent of some parties, and the Kurdish presence in the Constitutional Committee was limited to four people, including two from the opposition list, and two from the civil society list.

Despite media statements stressing that the Committee represents all the of Syrian society segments, Haji Mustafa considered that there is no real representation of the Kurds, and that there is no proper representation for civil society organizations in the Kurdish Autonomous Administration.

Haji Mustafa stressed that his name was excluded and withdrawn from the list of civil society, along with another name, because of the political tensions and polarization that played a major role, and because of the Turkish veto and the regime’s approval of this veto.

As for Ballan, he attributed the marginalization of the Kurdish component to two matters; the first is the president, due to the presence of Turkey and the agreement with the Russians, Iranians and the regime that there ought not be a Kurdish representation “as if they are a party on their own, and thus dealing becomes with different controlled regions and with nationalism.”

The other matter may be the announcement of the Constitutional Committee and the work in the civil society room to give legitimacy to the Turkish military operation (Peace Spring) launched in northeastern Syria against the People’s Protection Units on October 9, along with the regime’s entry and the sharing of the region.

Ballan talked about a meeting he attended a month before the announcement of the names in the Constitutional Committee in the Iraqi city of Erbil, with the participation of a group of Syrian organizations, from regime, opposition and Kurdish regions, and the presence of the political official in the UN envoy’s office.

Discussions were held and an agreement was at the time reached to represent all parties and not to exclude any of them. They were, however, surprised with the withdrawal of some names. Ballan pointed out that the exclusion of the Kurds is a previously agreed upon premeditated matter, since they do not want to recognize the existence of the Autonomous Administration as a military and political force, as it is backed by the USA.

Civil Society in Syria: “A Limited Development”Civil society is defined according to the United Nations as the third sector of society, along with government and the business sector, and it consists of civil society organizations and NGOs. This definition extends to include senior figures, including community leaders, professionals, such as lawyers and academics, and groups that seek to achieve general issues, according to a study by the LSE, on the list of civil society in the Syrian Constitutional Committee. The civil society has been rarely present in Syria during the rule of the former president of the Syrian regime, Hafez al-Assad, due to the concentration of the three authorities (legislative, executive and judicial) at one hand, which facilitated his control over civil society institutions. All this has led to their weakening and cancellation of their primary goal and turned them into a totalitarian regime instead of its civil form. According to a study of the British Christian Aid organization, published on September 18, prepared by meeting 25 participants from Syrian NGOs, in the repressive environment that Hafez al-Assad has administered since the 1970s, there were no necessary ingredients for the emergence of an important and pluralistic civil society, neither an independent civil society before 2011, within the state. Although there were 550 licensed organizations in 2000, they did not provide social services to the people due to the restrictions imposed on them. With the current president of the regime, Bashar al-Assad, assuming power in 2000, there was a short period of hope, called the “Damascus Spring,” that carried promises of freedom and openness, and witnessed brief activities of civil society, the emergence of independent newspapers, the release of political detainees and the formation of civil groups that focused on human rights. However, al-Assad soon felt that these moves represented a danger to his presence in power, so he sought to end them, and the term “civil society” turned into a sign of opposition. “There is only one society in Syria, it cannot be divided into civil and non-civil societies. There is one society, a civilized civil society,” al-Assad said in an interview with Al Jazeera in 2004. However, despite the repression, the first ten years of Bashar al-Assad’s regime witnessed a soft growth of civil society activities, including bloggers’ activities, anti-globalization movements and women’s rights campaigns. The civil society rapidly developed during the years of the Syrian conflict, taking advantage of the absence of the security authority and responding to the urgent needs created by chaos and human suffering. Organizations spread with the start of the popular movement, reaching 1,040 organizations until 2017, according to a survey conducted by Citizens for Syria organization. The reasons for these organizations’ spread included the decline in the role of peaceful activists with the tendency of the popular movement towards militarization, along with the increasing service needs that accompanied the decline of the role of the state in various Syrian regions. |

Attempts to exclude and dissolve

Is there an opportunity for the continuation of civil society’s role?

With the escalation of the division within the civil society delegation in the Constitutional Committee, voices came from within the “delegation coming from Damascus” to cancel the list of civil society. According to Enab Baladi’s information, one of the members of the “group coming from Damascus” described civil society as “a redundant third part.”

The member asked the delegation of the regime to add those coming from Damascus from the civil society group to its group. However, the pro-regime member of the “mini-group,” Mais Kreidi, denied this, and considered it part of the attempts to politicize the list.

Nevertheless, the civil society list is still in place, and is still being invited for the meetings of the Constitutional Committee. There are no talks about its official cancellation, according to a member of the delegation of the Mini-Constitutional Committee emanating from the civil society delegation, Sabah Hallaq, “on the contrary, work is now being done to strengthen the 50 members of the delegation through working on common concepts, providing support by Pedersen through experts, technicians and consultants, and holding workshops for all members to discuss constitutional principles.”

Her fellow member on the same list, Raghda Zaidan, stressed that civil society will not accept the cancellation of its list in the Constitutional Committee, and will insist that this does not happen.

On the role that the list can play in the constitutional process, a well-informed civil activist about the work of the civil society list in the Constitutional Committee (asked not to be named) considered that it is difficult to assess the situation of the list through the past first sessions.

On the expected impact of the civil society list, the activist considered that the largest bloc in the list is called 19 plus one plus 2, forming 22 people who are considered independent. If this bloc manages to expand more and include independents from the Syrian regime delegation, it can play a positive role by finding solutions, bridging the gap, and placing demands that are not related to power as much as they are related to Syrians’ needs.

For her part, Hallaq stressed that with the upcoming round of meetings, there can be consensus among the members. As for “homogeneity,” it is not necessary to happen. “Everyone is against terrorism; they are concerned with the territorial integrity of Syria and they have the same rights and duties.” Hallaq called for sitting at the same table and discussing consensus.

Mais Kreidi does not expect the civil society to fail, and believes that at one stage the disruption of the work of the committee can be eased, considering that civil society will affect every path in life and not only the constitutional process.

The CEO of Bercav Organization, Farouk Haji Mustafa, believes that the list of civil society is facing two merits: the first is how it must refrain from any project or methodology aimed at destroying Syrian civil society, and the second is the way of dealing with the Office of the United Nations Special Envoy to Syria, Geir Pedersen, and defining the form and the goals of the relationship with this office.

Opinions about the continuation of the civil society list work remain within the framework of expectations, while future rounds of the Constitutional Committee will determine the individual and collective intention to give the civil society delegation an intermediary role, which would contribute to achieving gains in the path of political transition.

if you think the article contain wrong information or you have additional details Send Correction

النسخة العربية من المقال

-

Follow us :

UN special envoy to Syria, Geir Pederson, talking about the meetings of the Constitutional Committee in Geneva – November 29, 2019 (Reuters)

UN special envoy to Syria, Geir Pederson, talking about the meetings of the Constitutional Committee in Geneva – November 29, 2019 (Reuters)

A

A

A

A

A

A

More In-Depth

More In-Depth