“When I was living in Damascus, people there used to call me the Turkish Nour. After I moved to Turkey, Turks call me the Syrian Nour,” said Nour al-Huda Abu Halawa in an interview with Enab Baladi. Between moving to and living in two different countries, the 25-year-old Abu Halawa tries to enjoy the advantages of dual citizenship, overcoming its drawbacks at the individual level.

Abu Halawa was born in Damascus to a Syrian father and to a Turkish mother. Her Turkish grandparents immigrated to Syria for business-related reasons. They obtained Syrian citizenship, benefiting from naturalization laws in the country.

Abu Halawa recalls the details about her family’s first immigration to Syria. When the grandparents divorced, her grandmother returned to settle in Turkey and remarried. Hence, her family split in two; Syrians living in Damascus and Turks living in the province of Hatay in Turkey.

Abu Halawa told Enab Baladi that her family used to live in the Turkish street in the of al-Salihia district in Damascus. Abu Halawa is familiar with the traditions of Turkish society because of her regular visits to her mother’s family in Turkey.

Abu Halawa speaks both Turkish and Arabic fluently. In fact, her mother’s plan was to teach Nour and her brothers the Turkish language alongside Arabic. This has helped them greatly after their arrival to Turkey in 2012.

Turkish Nour

There are similar stories about the reasons behind the immigration of Turks to Syria and their settling in the provinces of Aleppo and Damascus, after the Sanjak of Alexandretta (now the province of Hatay in Turkey) was officially annexed by Turkey in 1939.

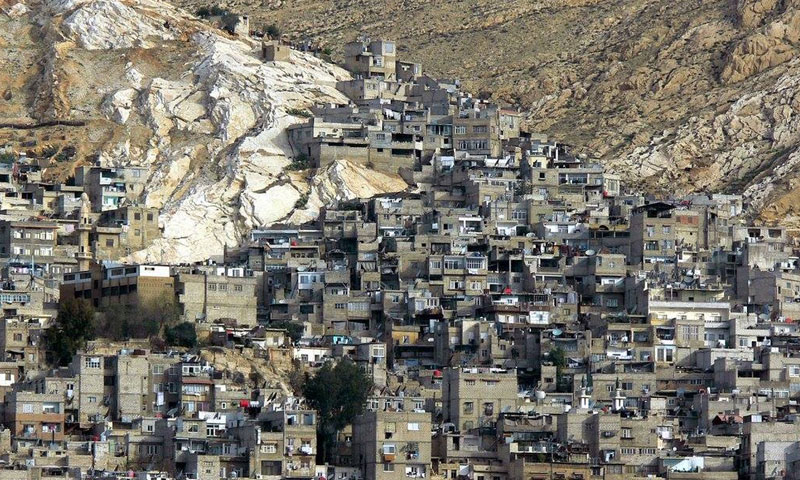

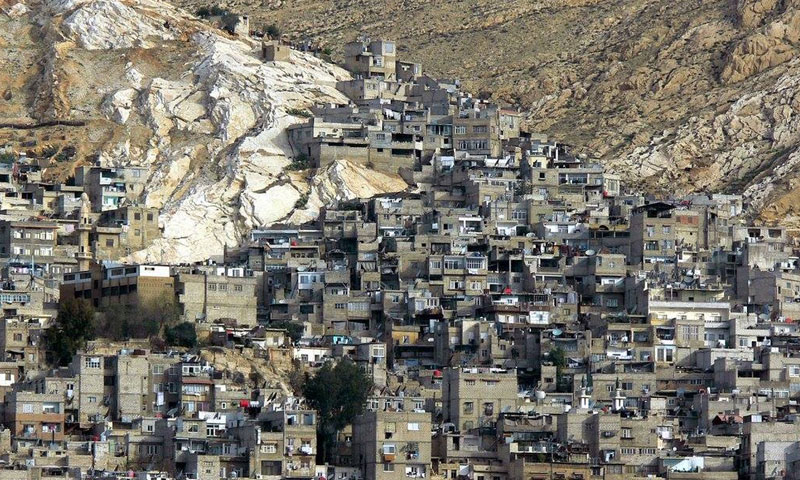

“The Turkish street”, where Abu Halawa used to live, was established by groups of Turks who arrived in Damascus in the first half of the 20th century. At the time, the residents of Damascus welcomed and helped them with building the neighborhood, which was an uninhabited mountainous area. Turks of Syria were involved in the trade of paper bags, which was not known among Syrians.

Turkish writer Sarhan Adah says in his book “The Problem of Hatay in Franco-Turkish Relations”, that after the annexation of Alexandretta, the French consul sent to the city of Antioch (the current capital of Hatay province) stating that the number of the population of the district, who chose one of the two nationalities—Syrian or Lebanese—is high. However, the agreement signed between France and Turkey led to the separation of the Sanjak from Syria.

The deadline for choosing one of the nationalities was over on 13 January 1940. At that time, the total number of emigrants from the Sanjak reached approximately 48,000. Of these there were around 26,500 Armenians,11,500 Orthodox Christians, 6,000 Sunni Arabs, and 3,000 Alawites.

After more than 70 years of these migrations, and with the outbreak of the Syrian revolution, part of the children and grandchildren of those families, who emigrated to Syria and settled there, came back again to Turkey, and were reunited with their families.

Alienation in the motherland

In a migration similar to that of Nour’s family, Zakaria Khoja’s parents (Turks by birth and descent) moved to live in Aleppo, Syria. Khoja was born and raised in Aleppo, yet he was surrounded by Turks for much of his life.

Part of his first-degree relatives are already registered in the General Registry Office in Turkey. Moreover, some even lived in Turkey. Old people within his family also speak Turkish and taught it to his two older brothers. However, Khoja could not master it, because the family moved to Saudi Arabia.

Khoja said in an interview with Enab Baladi, that he emigrated with his family to Turkey and reunited with the extended family in both its Turkish and Syrian members. Still, Khoja feels a kind of alienation and otherness “which often confuses him”.

Khoja says that he, “was bothered by the sense of alienation which I used to experience in Syria. Actually, I still feel alienated here in Turkey…it could be fear of the unknown and the future.”

He added that, “we used to be proud of our Turkish origin. And this is so natural as human beings, especially when we heard uplifting stories and positive attitudes towards our Turkish ancestors”.

Syrians of Turkish descent: in numbers

Meşküre Yılmaz, an assistant professor of history at Gazi University, wrote a book, called the Turkish World in which she devoted a chapter to talk about Turks of Syria. According to Yılmaz, many Turks, or as they are known by their popular name “Turkmen of Syria”, live today in the provinces of Aleppo and latakia. There are 265 Turkmen villages in Latakia. Turkmen are found in smaller numbers in Damascus and other areas.

Yılmaz says in her book that there are no official statistics on the number of Turks in Syria because the Syrian government subscribes to a strict ideology of Arab Nationalism. Yılmaz added that the estimated number of Turks living in Syria amounted to one million; 200,000 Turkmen in Aleppo, 150,000 in latakia, 50,000 in Tel Kalah in Homs countryside, 100,000 in Quneitra and 300,000 in other different areas.

Yılmaz pointed out that after the annexation of the Sanjak of Alexandretta, there was no clear policy or agreement between Syria and Turkey regarding Turkmen in Syria. Therefore, a mass exodus of Turkmen from Syria to Turkey took place between 1945-1953 in addition to individual emigration.

These immigrants, whose numbers are unknown, settled in the cities of Kirikhan, Alexandretta and Adana, in southern Turkey. The recent emigration took Khoja and Abu Halawa back to Turkey, but because of the war this time. They became official citizens of their home country.

Khoja acquired the Turkish citizenship exceptionally by a government decree and not by descent. He wished to obtain the Turkish citizenship by descent again because “he is proud of his Turkish origin and that gives him more confidence,” as he said.

Abu Halawa, who acquired citizenship by descent, is also proud to be Syrian and Turkish at the same time. She said that she wants to teach her children in the future that they are both “Syrian and Turkish”. She said that she “will take them one day to Syria after the war ends.”

“I will introduce them to the places where I lived, and I will teach them both languages as my mother did,” she says.

if you think the article contain wrong information or you have additional details Send Correction