Enab Baladi’s Investigation Team

Nour Abdel Nour | Mourad Abdel Jalil | Mais Hamad

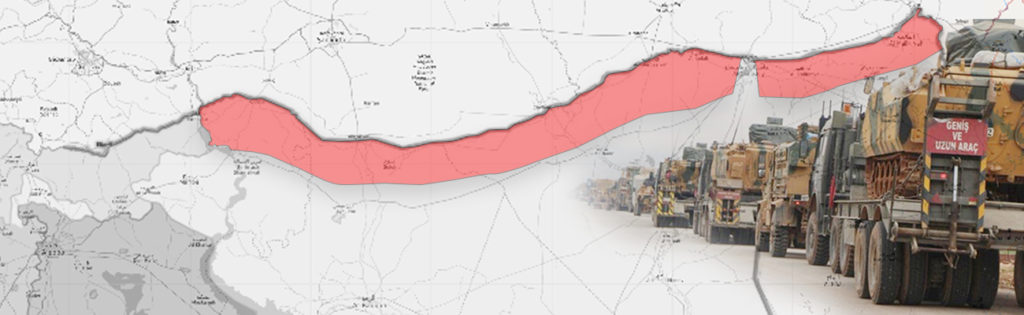

A new spot on the Syrian map is drawn by observers of US-Turkish statements, in a different color than the “yellow” that covers the northeastern part of Syria in military maps, pointing to a “safe zone” in a troubled country.

This spot, which forms part of the Syrian-Turkish borderline, opens the door to the application of Turkish-US understandings in the region, which mainly serve both sides’ interests, while the interests of the local parties associated with both of them are figured based on the final conception of that region.

Despite the ambiguity that still surrounds its details, the steps of the safe zone’s creation have started in an accelerated manner, amid a Turkish-American blackout regarding the provisional and final agreements related to the zone.

US and Turkish moves are met with local reactions ranging from rejection, confusion and full support to the idea of the creation of a safe zone.

In contrast, the Turkish proposal dominates most perceptions about the region and its military, political and service future, and forms the basis for building local positions towards it.

The safe zone is also driving the reasons for the talk about the Syrian refugees’ repatriation, since the zone will be protected by the concerned parties.

This file discusses the different perceptions of the shape of the safe zone to be established in northeastern Syria, and the positions of local, regional and international parties towards it. It also highlights the opposition’s movements regarding the future of that zone and the Kurdish fears from it.

Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) during the removal of military fortifications on the Syrian-Turkish borders. August 22, 2019 (Pentagon)

Shape… Depth… Impact

Safe Zone considerations subject to US and Turkish understandings

The idea of the creation of a safe zone in northeastern Syria is accepted and supported by local, regional and international organizations. The idea is only disturbed by the Syrian regime’s rejection, which is based on the principles of “sovereignty and legitimacy” and the concerns of its Russian and Iranian allies.

The United States and Turkey lead the positions of the rest of the local parties in Syria, on the outlines of shape and depth, on which details related to the future of the region, its management and its role in the desired political solution are being built.

Turkey insists that the safe zone be between 30 and 40 kilometers deep, with which it will ensure the restriction of the Kurdish presence, which is politically represented by the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (NES), and militarily by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), considering that a large part of that zone will be established in their areas of influence.

In contrast, the United States rejects that the safe zone be expanded over all that area, without declaring a final position of its depth, or a clear vision of its expansion.

Despite the US-Turkish disagreement over this detail, the two sides have taken joint steps to expedite its creation, as they both reached an agreement on August 7 on its creation.

On August 13, the establishment of infrastructure of the operation center in the Turkish Şanlıurfa Province for the management of the safe zone in northern Syria has started.

The first US assurances to Turkey have been manifested in the SDF’s destruction of military fortifications in the “safe zone,” on August 24, under the supervision of the International Coalition. The demolition took place “24 hours after a telephone conversation between the Turkish and US Presidents, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and Donald Trump, according to the Pentagon.

Shape of the zone from a local point of view

The Syrian political opposition adopts the Turkish point of view that the depth of the safe zone should be between 30 and 40 kilometers, according to the official of al-Jazira and Euphrates Committee in the National Coalition for Syrian Revolution and Opposition Forces, Yasser al-Farhan.

According to al-Farhan, the opposition also aspires to extend the depth of the safe zone for more than 30 kilometers from the Turkish borders, to include the rest of the al-Hasakah Governorate, and the governorates of Deir ez-Zor and Raqqa.

However, this perception does not fully satisfy the Kurds, whether the Kurdish National Council, which is affiliated in the National Coalition for Syrian Revolution and Opposition Forces, or the Autonomous Administration.

Fouad Aliko, a member of the Kurdish National Council, believes it is too early to make a clear and explicit position on the safe zone, noting the importance of creating it as an alternative solution to the military intervention.

“We do not determine and have no role in determining the depth of the safe zone. It is rather the US-Turkish agreement that determines it. What concerns us is to provide security and stability in that zone and to facilitate the return of refugees to their areas and houses,” Aliko added in an interview with Enab Baladi.

The Syrian Democratic Council (SDC), the political wing of the SDF, aspires that the safe zone brings stability to the east of the Euphrates, but “through protection against Turkish threats,” said SDC Spokesperson Amjad Othman.

“What has been agreed upon so far is that the zone will be between 5 and 14 kilometers deep,” Othman added in an interview with Enab Baladi.

Fears of division

The Syrian regime rejects US-Turkish understandings on the creation of a “safe zone” in northeastern Syria and considers it an “undermining of Syria’s sovereignty.”

An official source at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Expatriates described on July 26 to official Syrian news agency SANA the US intervention in Syria as “destructive” and the US-Turkish understandings as “a blatant attack on the sovereignty and unity of the Syrian land and people, and a flagrant violation of the principles of International Law and the Charter of the United nations.”

Russia, which has been excluded from the coordination of the implementation of the safe zone’s steps, has warned of what it called attempts to divide northeastern Syria, expressed the Spokeswoman of its Foreign Ministry, Maria Zakharova, who considered that “the international legitimacy requires the approval of Damascus on any operations that would take place on its lands.”

Russia called for dialogue between the Autonomous Administration and the Syrian regime, saying: “We are still supporting a long-term stability and security in northeastern Syria by consolidating Syria’s sovereignty and holding a fruitful dialogue between Damascus and the Kurds, as they are both parts of the Syrian people.”

As for Iran, it has attacked the Turkish-US agreement on the “safe zone” in northern Syria, considering it a “provocative and worrying” step.

Iranian Foreign Ministry spokesperson Abbas Mousavi said on August 18 that US officials’ statements and their agreement to create a safe zone in northern Syria “contradict the principles of International Law and the Charter of the United nations.”

The official considered that “like other US officials practices, such actions cause destabilization,” and are considered “an interference in Syria’s internal affairs.”

The concept of safe zone in the International Law

The term “safe zones” is not technical in itself in the International Law. It is rather used to describe a variety of situations, including safe zones stipulated by the International Humanitarian Law and other types of safe zones.

Rule 35 of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) study on customary international humanitarian law, applicable in non-international armed conflict, provides for three types of safe zones: “hospitals, safety zones, neutral zones, demilitarized zones, open cities and demilitarized sites.”

International law prohibits targeting hospitals and medical treatment areas unless they are used for military purposes. In addition to these protective measures, the conflicting parties may agree or recognize any zone as a “safe zone,” which may be a hospital, a neutral civilian area, or any other kind of locations mentioned in the previous paragraph.

Under the agreement, the warring parties are obliged not to use the area for military purposes, such as storing weapons or hiding fighters. However, wounded combatants from both sides may be accommodated in these areas, and therefore not to be targeted militarily as well.

Examples of safe zones that had historically been established by mutual consent under these provisions of international law include safe zones in the 1971 Bangladesh War, in Cyprus (1974), in Nicaragua (1979), and in Chad (1980).

The second type of safe zones has begun to emerge in recent decades because of the failure of the safe zones mentioned in international humanitarian law to effectively protect and secure civilians from the effects of armed conflicts.

This type of safe zones, protected by military personnel, is usually established by the United Nations Security Council without the consent of all conflicting parties. However, announcing a particular zone as a safe zone is challenging since it requires the intervention of United Nations armed forces.

Source: Syrian Legal Development Office

Syrian opposition: Anticipatory presence in safe zone particularities

In light of the Turkish-American understandings and repeated statements by officials from both sides, during the past weeks, the absence of a vision of the Syrian opposition represented by the Syrian National Coalition (SNC) over the region is remarkable, with the exception of statements by opposition officials on the Turkish and local media, supported the Turkish view on the depth and importance of the region, especially with regard to the political solution and the return of displaced refugees to their areas.

Turkey is one of the largest supporters of the Syrian opposition, as the Turkish authorities have received nearly four million Syrian refugees on its territory, and supported two military operations in the areas of the countryside of Aleppo (the Euphrates Shield and Olive Branch), to become the first responsible party for the file of the Syrian opposition, amid questions about the opposition’s vision, whether by the SNC or its Interim Government.

To find out about the equipment and vision of the Syrian opposition, Enab Baladi attempted to talk with the interim government about its future plans to manage the safe zone in case it is established. However, the current government is stalled until a new one is formed.

Dr. Abdul Hakim al-Masri, an economist who was an assistant to the minister of economy in the outgoing Syrian Interim Government, stressed that “the interim government is always ready; it has been formed to serve the region and its population. The Interim Government’s institutions and directorates are fully ready for any work within the safe zone and under its supervision.”

Ongoing coordination with Turkey

For his part, member of the political body in the opposition coalition, Yasser al-Farhan, confirmed that “the coalition coordinates with Turkey all the issues on the basis of a solid intersection of interests and values. Turkey is a strategic ally of the Syrian opposition,” while Turkey considers the coalition as a key partner. These official stances have been confirmed in the last meeting of the President of the Alliance, Anas al-Abdeh, with the Turkish Foreign Minister, Mevlut Cavusoglu, on Tuesday, 20 August.

Al-Farhan said that what concerns Turkey is its national security, and that it wants to establish a safe zone in order to protect its borders; while the establishment of the safe zone concerns the coalition for two reasons: the first is “to protect the security of a neighbor and friendly state,” and the second is “related to the interests of Syria and the Syrian people.”

He continued: “The safe zone supports and creates suitable conditions for the political process, as an opportunity to form an opposition force, and counter the unilateralism of the Syrian regime, which is trying to control large areas militarily, and impose military hegemony at the negotiating table.”

He added: “The aim of the safe zone is to preserve the unity of Syria, secure the return of displaced people, and rid the region’s population of the Democratic Union Party (PYD), which is oppressing people and imposing unacceptable regulations.”

With the different visions about the size of the safe zone between the Turks and the Americans, the Syrian opposition adopts Turkey’s vision. It is important that the area reaches 30 kilometers into the Syrian deep, and the entire area in Deir ez-Zor and the rest of al Hasakah and Raqqa, according to al-Farhan, who suggested that the area to be managed by locals under the supervision of the SNC.

The opposition is ready to manage the region

The idea of establishing a safe zone is not recent. The idea has been considered since the beginning of the escalation of military operations in Syria and the return of thousands of people to Turkey.

During recent weeks, Ankara’s insistence on establishing a safe zone as a “peace route” for political reasons linked to the protection of its borders has raised questions about the economic potential of the safe zone and the steps as well as equipment to be provided out there in order to accommodate hundreds of thousands of refugees intended to be sent back by Turkey.

“The zone needs great potential, plans and strategy to manage it, and the SNC and the Interim Government are working on all these,” al-Farhan asserted. He also stressed that the SNC has “the Island and the Euphrates committee,” which includes the locals of the eastern region. He conveyed that the committee has established a vision to manage the region temporarily by its people and preserve the unity of Syria; while drafting ideas correlated with a mechanism of peace and justice in order to maintain the region’s security.

According to al-Farhan, studies have also been prepared for the safe zone, the number of its residents and potential returning refugees, including their educational, health and services needs, i.e. water, electricity and transportation; in addition to the region’s need for economic resources and human resources. He stressed that these studies are based on more than one scenario.

The Interim Government also has three files, 120 pages each. Each file includes an integrated plan to manage the safe zone, protect its people and prevent abuse, as well as ensure stability and “get rid of terrorist groups, while blocking the return of ISIS groups,” according to al-Farhan, who pointed out that the regions’ wealth, including wheat, oil and water, will stimulate its economy and ensure stable living conditions for its people.

Plans for the zone’s economic future

“Before talking about the return of any refugee, it is necessary to secure housing, rehabilitate the infrastructure of water, electricity and roads, as well as build hospitals,” said Dr. al-Masri.

Speaking to Enab Baladi, al-Masri stressed the need to pay attention and support the educational sector in all of its stages with the aim of re-settling academics and experts, stopping immigration and allowing students’ return.

According to al-Masri, “despite the great resources needed to establish the safe zone, the Turkish supervision, in case it is formed “will lead to the cooperation between the opposition and Ankara in the light of human resources in the region, in addition to the possibility of providing financial assets through the imposition of customs duties and trade with Turkey. ”

He continued: “If there is security in the zone, this will allow investors to enter it and implement projects in all fields.”

Turkish Foreign Minister, Mevlut Cavusoglu, and President of the Syrian National Coalition, Anas al Abdeh – August 20, 2019 (SNC)

Will Syrian refugees return to the Safe Zone?

The establishment of the “safe zone” puts this solution into question, making one wonder whether it was meant to push forward the process of repatriation of refugees in neighboring countries to Syria, since the zone covers a relatively large area in northeastern Syria, according to the Turkish vision.

Enab Baladi asked readers and Facebook page followers the following question: “In case a safe zone is established in northeastern Syria, would it offer refugees the chance to return to Syria? Why?”

Some 69% of the respondents, equal to 2700, answered “No,” while other 31% said “Yes.”

The opinions of the users reacting to the opinion poll were divergent, for the ones who said no justified their position in different way. For instance, Abdul Rahman al-Moallem said it would not be as safe as Idlib, and that “its guarantors would not move to react.”

“The majority of refugees originally belong to the western, central and southern areas of Syria, and are not from those places (northeastern Syria). They won’t exchange an external asylum with an internal asylum,” said Zakaria Hijazi.

“Would people leave their homes and villages? Did the revolution break for this reason?” Meanwhile, Osama al-King questioned the capacity of the area, and the extent to which it can be safe from the bombardment of regime forces.

Ahmed Ibrahim says that the area “does not provide life essentials, and it is remote. Cities do not offer services and job opportunities too.” Amer al-Omari, agrees with Ibrahim arguing that “the safe zone is a large prison securing no life essentials.”

“Safe” for opposition… “confusing” for Kurds

Fears of “comprehensive” change in eastern Euphrates

While the Syrian opposition is taking action following “planning and implementation” logic, despite the uncertainty of the future of the safe zone solution, confusion dominates the Kurdish position, fearing the change that may occur at the level of power and administration in the region, in addition to “demographic change.”

The Syrian Democratic Council (SDC) spokesperson, Amjad Othman, stressed that the Council insists on maintaining the structure of the existing Autonomous Administration, which provides services to the people in the region, and believes the protection of the borders of this region must be the responsibility of “military councils consisting of locals.”

On the other hand, the Kurdish National Council believes that it is too early to adopt a clear and explicit position regarding the region, according to one of the members, Fouad Aliko.

“The Council supports the safe zone solution provided that its security and management staff shall consist of the region’s various ethnic components, including Arabs, Kurds, Turkmen, Syrians, and others, because this would ensure security, stability and the return of refugees to their homes.” The Council also stipulates that the zone shall be subject to national coalition supervision, including Turkey.”

“Conditional” Return of refugees

The safe zone is coupled with the refugee issue, for it will offer a secure geographical area that will allow some Syrian refugees to return, with international regional consensus.

However, the issue is translated into fears for the Kurdish political parties, regardless of their orientations, especially in reference to Syrian refugees in Turkey, who do not belong to eastern governorates.

“Hundreds of thousands of refugees belonging to the eastern Euphrates, Deir ez-Zor, Raqqa, al-Hasakah and Kobanî are living in Turkey and have the right to return to their homes,” Aliko said.

“As for refugees from outside the zone, we do not prefer this because it would create problems between them and the people of the zone, to which we are indispensable.”

The Syrian Democratic Council shares the same position of the Kurdish National Council. Amjad Othman said: “Only the return of each refugee to his own home is approved; whereas, Turkish statement providing for the repatriation of about 70,000 refugees has nothing to do with us.”

Demographic change

Othman criticized the process of “taking advantage of refugees to achieve political agenda,” saying: “We refuse to use refugees to make demographic changes and tamper with the demographics composition of Syria for any aims or goals.”

The media coordinator of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), Ibrahim Ibrahim, considered the safe zone as an occupation of northern Syria, and a “genocidal war” aiming to drive the Kurds out of their villages, causing four million Syrians to suffer a humanitarian crisis.

Nawaf Khalil, head of Germany-based Kurdish Center for Studies (KCS), told Enab Baladi that “the safe area is home to five million people, one million of whom are displaced, according to the Autonomous Administration’s statistics.” He pointed out that part of the population could be displaced to allow others coming in, just like “Afrin experience.”

Concerning the fear of any demographic change, Khalil clarified that “the issue is not only related to the Kurdish population, but to Syrian refugees as a whole, for there are Syriacs, Assyrians, Kurds and Arabs.” Turkey is very good with demographic engineering, the Syriacs and Armenians for instance, and Afrin too, where Ankara started displacing people and ended up attributing the names of historical and political Turkish symbols to its streets. ”

“The nightmare of Afrin”

Most of the Kurds that Enab Baladi met, including leaders, activists, researchers and journalists, consider the issue of the safe zone as a reenactment of the “Afrin scenario.”

Fouad Aliko, member of the Kurdish National Council, said that “what is happening in Afrin now and other people coming from other areas seizing homes and property of citizens, imposing illegal taxation, and military factions arbitrary arresting citizens, confirms our concerns about the return of refugees to regions other than their own.”

The media coordinator of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), Ibrahim Ibrahim, insisted: “What happened in Afrin is enough to reject any dictations from Ankara. The safe zone is an argument that has received strong Russian and Iranian support.”

The Kurdish political activist, Abdul Qader Akoub, perceives the creation of the safe zone from a different angle, saying that “the scenario of Afrin will not be repeated, for the first battle was one-sided, and convergence today is the best solution that exists. Washington is still the guarantor of the agreement, which serves the interest of the Kurds wishing to return from Turkey. ”

Coalition reassures

While Kurdish concerns dominate perceptions involving the safe zone, the National Coalition believes that its formation will not have a negative impact on the population.

Yasser al-Farhan, member of the political body of the Coalition, told Enab Baladi: “The Syrian territory is for all the Syrian people. When a humanitarian catastrophe occurs because of the brutality of the regime inflicted on the people of the region, we won’t be thinking that such issue will make a demographic change, for refugees are returning to Syrian territory. This is a degrading discussion that is not worthy of the Syrian people. The people of the other areas who are going to come to that area will of course come in a temporary situation. ”

Al-Farhan accuses the Autonomous Administration of having an agenda abroad that determines its attitude towards the return of refugees, “unlike the region’s Kurds, Arabs, Syrians and Assyrians.”

“The return will be voluntary and safe; so many people in the region will be willing to return.”

Al-Farhan believes that political gain is greater than the concerns raised about the refugee issue. “When there is a non-regime or PYD forces in the region, this will lead to political balance and the imposition of military dominance at the negotiating table; thus, a temporary safe zone will be established until the conclusion of political solution.

Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) during the removal of military fortifications on the border with Turkey August 22, 2019 (Pentagon)