Enab Baladi’s Investigation Team

Reham al-Assaad | Haba Shahadeh | Ninar Khalifa

The arrest of the American tourist Sam Goodwin by the Syrian regime had not been announced, until his release on July 26, under Lebanon’s mediation.

Goodwin’s case was kept secret until its closure after he spent 62 days at the cells of the Syrian regime, during which negotiations were held for his release, and mediated by the director general of the Lebanese security, Abbas Ibrahim.

The young American traveler, 30, was arrested without charge. His only guilt was wandering in the streets of the city of Qamishli in his endeavor to achieve his tour around the world.

Goodwin is one of dozens of foreigners detained by the Syrian regime for eight years. With the enactment of the “terrorism” law on July 2, 2012, which adopted a “loose” version including all opposition activities, according to Human Rights Watch, arrests have since been carried out under a legal cover.

Human rights organizations concerned with detainees’ cases have been able to document cases of detention of foreigners in Syria, including Arab, American, British, and German journalists, doctors, and activists.

Over the past year, there have been increasing arrests of tourists, including more than 30 Jordanians arrested in Syria after the opening of Nasib Border Crossing last October.

The Syrian Center for Media and Freedom of Expression at the Syrian Journalists Association has documented 29 cases of arrest, detention, or abduction of non-Syrian journalists since March 2011, the director of the center, Ibrahim al-Hussein, told Enab Baladi.

The center has been able to ascertain the regime’s responsibility for the arrest of nine of them, five of whom were released, and four others remained under the pretext of either “not obtaining permission to enter Syria” or “not obtaining permission to practice media work,” according to al-Hussein.

In this file, Enab Baladi monitors the most prominent arrests carried out by the regime against foreigners in Syria and highlights the reasons for keeping them secret and not disclosing the real motives of for the arrest. The file also sheds light on the legal context in which these arrests are carried out.

Turkish journalists protesting in front of the Syrian embassy in Ankara to demand the release of journalists Bashar Fahmi al-Kadumi and Cüneyt Ünal – August 31, 2012 (AP)

Under the table: International moves to release foreign detainees

At a time when the Syrian regime has been denying the presence of foreign detainees in its prisons, international mediations have suddenly appeared to exert pressure on the regime to release foreign citizens who had been detained in mysterious circumstances. Few movements have succeeded in releasing some of them while most of them failed.

In light of the diplomatic boycott the Syrian regime has faced in recent years, some countries have found it difficult to communicate with the regime to discuss the file of foreign detainees, prompting them to find mediators from countries that have maintained relations with the Syrian regime, or its allies.

Jordan and Lebanon issue a position

Lebanon has suddenly imposed itself, with US pressure, in the negotiations field on foreign detainees when the Syrian regime released American citizen Sam Goodwin.

Lebanon still faces obstacles concerning its citizens detained in the regime’s prisons, in light of the political split on the Lebanese scene between those close to and those opposed to the Syrian regime.

The last Lebanese move in the file of Lebanese detainees was on August 8, when the Lebanese Forces Party handed over a list of Lebanese detainees in Syrian regime prisons to the UN envoy to Syria, Geir O. Pedersen, in an attempt to reveal their fate after decades of detention.

Since its entry into Lebanon in 1990, the Syrian army has arrested hundreds of Lebanese people on various political charges. Official authorities are still demanding their release and reveal their fate; but the Syrian regime is still silent about the matter.

As for Jordan, it handed over a list of Jordanian detainees in Syrian prisons to the Syrian Embassy in Amman on July 21, coinciding with the end of the work of the Chargé D’affaires, Ayman Alloush.

In addition, Jordanian Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Sufian al-Qudah summoned on April 4 the Chargé D’affaires of the Syrian Embassy Ayman Alloush to demand the immediate release of all Jordanian detainees and implement international laws.

Canadian tourist, Kristian Lee Baxter, during a press conference in Beirut alongside the General Director of the Lebanese Security Abbas Ibrahim – 9 August, 2019 (AFP)

Russia: The Pressure Ally

Being the political and military ally of the Syrian regime and having a prominent international position, some Western countries, especially the United States, sought to resort to Russia in order to exert pressure on the Syrian regime to release its detained journalists and foreign citizens.

In 2016, Russia acknowledged its contribution into the release of American journalist Kevin Dawes, whose detention the Syrian regime denied in 2012 and who was released four years later. During this period of time, he was only allowed to communicate with his family days before his release.

The US State Department, which acknowledged Russia’s role in Dawes’ release, did not elaborate on the details of the operation, the reasons behind his arrest, and the secret of his release.

“We appreciate the efforts of the Russian government to save this American citizen in Syria,” said the spokesperson of the State Department, Mark Toner, during a news conference at that time.

US Presidential Envoy for Hostage Release Robert O’Brien also asked for Russia’s help, in November 2018, to rescue American journalist Austin Tice, kidnapped in Syria since 2012.

However, all American attempts to release Tice have failed, despite all the negotiations carried out until today.

Under Russian pressure, the Syrian regime, released German journalist Billy Six, aged 26, in March 2013 two and a half months after his arrest, on charges of “illegally” entering Syria and infiltrating regime areas through opposition areas.

The handover process took place between Syrian Deputy Foreign Minister Faisal al-Miqdad and the former Russian ambassador to Damascus, Azmatullah Kul Mamadov.

Czech: The US Official Mediator

The Czech Republic has maintained its relations with the Syrian regime since 2011, making itself the “semi-official bridge of the United States” to negotiate the file of detainees with the Syrian regime, according to the New York Times report published in December 2019.

Czech declared its efforts aiming to release two US citizens of Syrian origin, namely Majd Kamalmaz and Layla Shweikani. However, unlike the Russian, the Czech mediation was not successful.

The first Czech mediation occurred 10 months after the arrest of the Syrian-American girl, Layla Shweikani, when the Czech ambassador in Damascus, Eva Felipe, visited her while in Adra Central Prison on behalf of the US.

Shweikani “confessed” the “crimes” the Syrian regime has accused her of committing to the Czech ambassador, according to a report published by the Independent newspaper in December 2018. The report pointed out that the Syrian regime threatened to harm Layla and her family “in case she did not confess before the ambassador”.

According to the newspaper, Layla was transferred eight days after meeting the ambassador to Sednaya prison where she was executed and her family was later notified about her death in November 2018. The White House or the State Department did not issue any statement regarding the circumstances of her death as a US citizen.

Czech second attempt as a mediator was meant to release the American detainee of Syrian origin Majd Kamalmaz, who was detained by the Syrian regime in 2017 in Damascus. Shortly after his disappearance, the Czech Embassy asked the Syrian regime to report his location. The regime then declared Majd Kamalmaz to be detained inside one of its prisons, but then backed down, according to the New York Times.

In a report published in 2019, the newspaper revealed that Majd’s family, living in the US, reached out to the FBI and the US State Department to release him, but both recommended the family not to stay quiet about his disappearance until negotiations would succeed. However, Majd is still missing until today.

Why is the regime being secretive about foreign detainees?

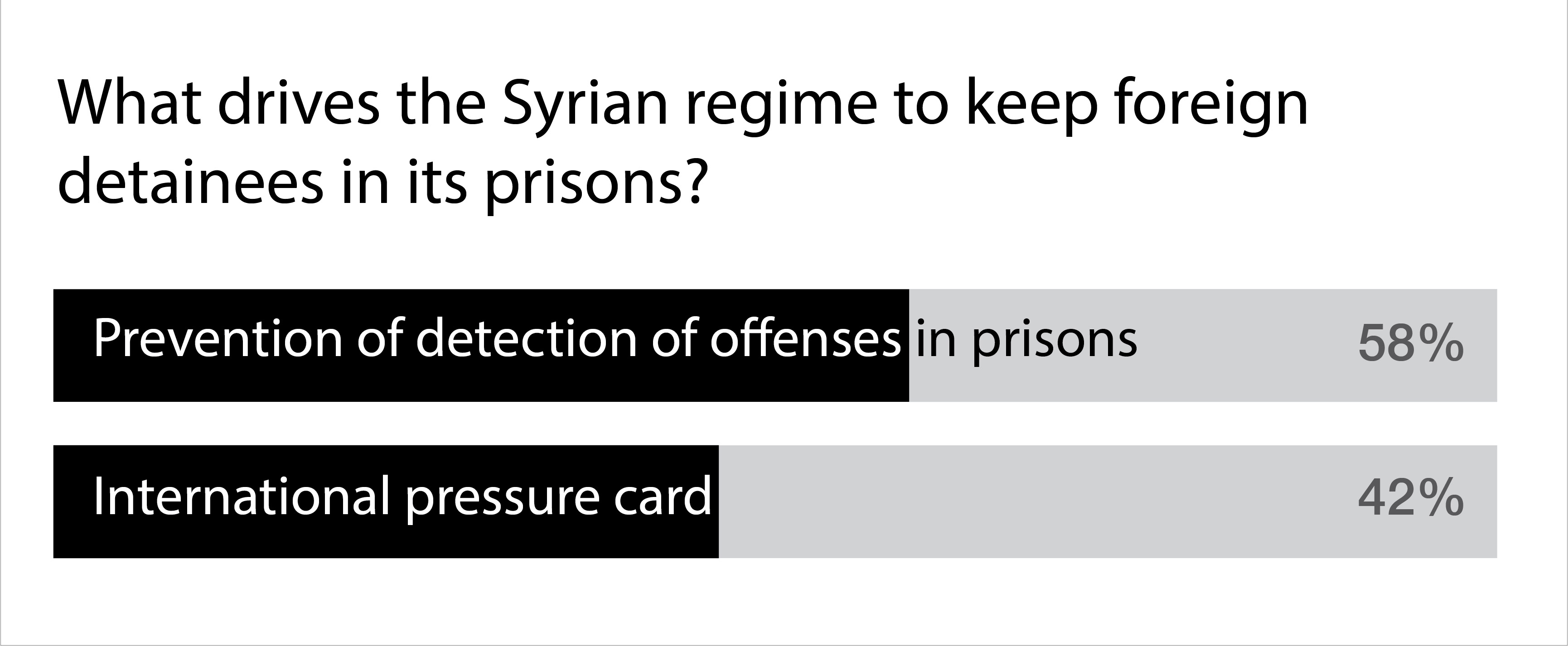

Opinion poll

The Syrian regime is being very cautious and discreet about the issue of foreign detainees inside its own prisons, disclosing no information about them, while international mediation often reveals the names and circumstances under which some of these arrests are carried out.

Political and academic researcher, Samira Moubayed, believes that the large number of security branches affiliated to the regime and separated from one another is encouraging it to deny under the pretext that each branch does not know anything about others detained in other branches. Such separation helps the regime withhold information and deny international actors and press access to it.

Referring to the reasons why the Syrian regime does not recognize the presence of foreign detainees in its prisons, Moubayed pointed out that there are several motives preventing the regime from disclosing information about them, mainly “evading international responsibility and prosecution in case the regime decided to acknowledge the presence of foreign detainee; thus, condemning it in the future.”

The pressure card

“The regime may use these detainees as a pressure card, hiding them and then announcing their presence at certain moments through internal negotiations with the concerned countries. As a result, the regime may achieve gains and demands, ensuring that detainees would not disclose any of what they have seen inside the detention centers,” said Moubayed during an interview with Enab Baladi.

She added that “arresting foreigners may help the regime condemn opposition factions and Islamic militant organizations before the international community, accusing them of arresting and killing foreign journalists and citizens,” as in the case of American journalist Austin Tice.

“However, after clearing the prisons of the opposition factions and militant organizations, it has become clear these names do not exist there. The regime has benefited from procrastination and blaming the factions by virtue of their existence during the past period.

As for foreign journalists kept in the Syrian regime’s prisons, Moubayed believes that “denying their existence and even eliminating them better serves the regime’s interest as they possess information and evidence that condemn its activities.” If the regime admits their presence and allows them to communicate with external parties, they will be able to deliver and share information that exposes and convicts the regime of committing crimes against humanity. They will also report what they saw in Syria in and inside the detention centers in particular.

“Limited” international action: Why?

Despite the several cases during which countries have taken action to release citizens detained at the regime’s prisons, political researcher Samira Moubayed believes that secret moves are much greater, for those countries want to make sure to avoid media escalation that could endanger the detainee’s life.

“In case of any media whirlwind addressing any foreign detainee, the regime may end up hiding or killing him or her, obliterating evidence and accusing the opposition factions of arresting him or her to avoid international prosecution,” Moubayed said.

“When the regime denies the existence of foreign detainees, countries may indirectly rely on other sources to ensure this person exists in one of its prisons. However, in this case they will not have any official document convicting the regime, forcing them to resort to secret negotiations with the government in exchange for benefits”.

Moubayed pointed out that with the proliferation of the news tackling the death of a foreign detainee in the regime’s prisons the media starts to take action, as countries have lost any possibility of liberating the detainee and pushing the case to the public opinion, as in the case with the American-Syrian detainee, Layla Shweikani.

“Legal cases should play an important role, for the relatives of a foreign detainee who was murdered under torture are pressing charges and lawsuits against the Syrian regime for future conviction of committing crimes against humanity,” she said.

“War crime”: Will the regime escape accountability for foreign detainees?

While the issue of foreign detainees remains subject to secret talks tackled whenever a government is trying to reclaim its citizens, or when someone is released thanks to an international mediation, the extent of the lawfulness of the regime’s detention of these foreigners is called into question.

Lawyer and former chief negotiator of the opposition, Mohamed Sabra, pointed out that all legal systems in the world take root in the validity of punitive laws reigning in the national territory (the country where the person is located) regardless of the perpetrator.

During an interview with Enab Baladi, Sabra said that although this is a general root, the Syrian regime, from a very early period dating back to the early 1970s, abducted some opponents and citizens of other countries (whether neighboring countries or others) and took them to detention in Damascus without any legal cause.

Sabra revealed that the regime previously abducted hundreds of Lebanese, Palestinian, and Jordanian citizens on the border. Some of them were about to enter Syrian territory, or brought from Lebanon.

Hundreds of them are still missing today, “especially the Lebanese who were kidnapped from Tripoli in 1986, after Bab al-Tabbaneh massacre, or from Beirut after the Syrian regime re-established control over it in 1984,” Sabra said.

Sabra recalls some of the names representing political and social leaders in their countries, such as Ibrahim Kulaylat from Lebanon, and Hakem al-Fayez from Jordan, who spent more than 20 years in regime detention, along with many others.

“War crime”

Sabra stressed that the regime’s previous and ongoing actions are to be considered as a “war crime” and serious violation of international human rights law, whether the arrest taking place on Syrian soil, or kidnapping people from outside, especially if the reason behind these arrests is disagreeing with the regime and its political vision.

Sabra pointed out to the “failure to raise this issue at the regional level, because those affected by the criminal behavior of the regime are many, and they are citizens to almost all neighboring countries.”

He underlined the importance of taking action so as to “form a united front bringing together regime’s victims from neighboring countries, in coordination with the Syrians. This front will be responsible for pushing the case forward and bringing the regime before international tribunals and prosecute it for the crimes it has committed in Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq, and the Palestinian camps in Lebanon.”

“Violating the Treaty of Rome”

Attorney Mohammed Sabra pointed out that the regime arresting foreigners and getting them killed sometimes is a serious violation of the Treaty of Rome, the founder of the International Criminal Court, which regulates the way signatory states’ are dealing with crimes having international impact.

This applies, for example, to the case of the abducted British doctor, Abbas Khan, who was killed under torture in the regime’s prisons in 2013, given the fact that his country is a signatory to the Charter.

Sabra believes “these criminal acts have not enough access to the Western public, although they themselves constitute evidence of the scale of violations committed by the regime.”

He stressed that several attempts have been made to transfer the case of Doctor Abbas Khan to the International Criminal Court, but considering that Syria is not a signatory to the treaty, it requires the intervention of the Security Council. “Currently, this is considered to be very difficult due to the veto, used 14 times to thwart any serious attempt to refer the file of violations of the regime to the International Criminal Court,” according to Sabra.

Two alternatives to Justice

Although the regime has so far escaped accountability for what it has committed against foreign detainees, Sabra pointed out that “two influential ways can be taken to reach a breakthrough in this file.”

First, it shall be referred by the United Nations General Assembly on the basis of the principle of the Union for Peace, and second, to form an international human rights coalition that presses in this direction and demonstrates to the public the magnitude and type of violations of the regime according to international law.

Sabra believes that the next stage will bring positive developments in this file, for “there is currently serious work and movements in order to bring justice to the victims that is necessary to reach any peace in Syria.”

Fatma Khan, mother of British surgeon Abbas Khan during his mourning service – 26 December, 2013 (PA)

if you think the article contain wrong information or you have additional details Send Correction

النسخة العربية من المقال

-

Follow us :

Mark and Debra Tice standing in front of the photo of their kidnapped son Austin Tice after a press conference in Beirut - December 4, 2018 (VOA)

Mark and Debra Tice standing in front of the photo of their kidnapped son Austin Tice after a press conference in Beirut - December 4, 2018 (VOA)

A

A

A

A

A

A

More In-Depth

More In-Depth