Enab Baladi’s Investigation Team

Hala Ibrahim/ Reham al-Assaad/ Murad Abdul Jalil/ Nour Dalati

In 2014, the Simon Wiesenthal Centre, which campaigns for the prosecution of Nazis, suggested that Alois Brunner, one of the last Nazi war criminals to be persecuted, had died in Syria four years ago.

The announcement of Brunner’s death at the time was reminiscent of one of the most obscure personalities, as the Simon Wiesenthal Centre described him; given the paucity of information on his case, which began when he left Germany at the end of World War II and arrived in Syria in the early 1950s. For almost 60 years, Brunner has been protected in Syria from international prosecution.

Brunner, who lived in the Damascus suburb of Rawda under the name of George Fisher, did not reveal his real identity to his Syrian neighbors, but his presence in Syria was not a secret to the European intelligence services, according to the US-based centre.

Claims to prosecute Brunner on charges of mass murders in Germany have been recurrently reiterated until 2008, two years before his death.

The French newspaper, Revue 21, published a report last year, stating that Brunner had paid for his own safety, insured by the Syrian regime, by providing advising services for Hafez al-Assad unofficially, contributing to the construction of “al-Assad’s terrifying intelligence system.”

| “Ansar Allah is a Palestinian armed group founded in 1990 as a battalion affiliated to the Palestinian movement Fatah, but its support and proximity to Hezbollah has led to its separation from Fatah.” |

Brunner’s story, which has been an intriguing case for intelligence systems all over the world, was not the last one where the Syrian regime protected a fugitive from justice; a practice which became more observable after the Syrian revolution.

Despite Syria’s commitment to international and regional extradition treaties, any judicial decision to deport any wanted fugitive to his/ her country is not binding to the Syrian executive branch, which has the freedom to implement such resolution or reject it.

The latest incident took place this month when the General Secretary of the Palestinian organization Ansar Allah, Jamal Suleiman, fled the Mieh Mieh Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon to Mezzeh in the Syrian capital.

The Lebanese National News Agency NNA reported that Suleiman fled with 17 members of his family and siblings, in addition to a number of his companions, after the Palestinian camp witnessed armed clashes between Ansar Allah, Fatah and the Palestinian National Security Forces.

The Syrian regime did not comment on or admit the presence of Suleiman on the Syrian territory, which also happened in the case of Lebanon’s notorious drug lord Noah Zaiter, and Yusuf Nazik, who was accused of mapping out the 2013 Rihaniyah bombing in Turkey and other wanted criminals.

Incidents the Syrian regime contained

International wanted fugitives in al-Assad’s stronghold

Either as an individual murder or as abuses committed by organized gangs, the common solution between them consisted in the perpetrators’ escape from the crime scene to a country that offers protection in one way or another, saving the runaways from their inevitable fate; as they may be thrown behind prison bars or executed if they stayed.

These incidents were repeated during a period where Syria went through a state of security breach at the level of borders and border crossings. It was a safe haven for a number of runaways who were prosecuted legally and judicially in several countries around the world.

Yusuf Nazik: The Turkish Intelligence operates in Syria

Yusuf Nazik, was arrested during an operation that the Turkish National Intelligence Organization described as highly efficient. Nazik was accused of plotting the 2013 Rihaniyah bombing in Turkey, which killed 53 people and left a number of wounded casualties behind.

The operation’s distinctiveness was attributed to the fact that it was carried out inside Syria, last September. The Turkish Intelligence transferred the offender from Latakia to Turkey via “safe” roads, and interrogated him till he admitted that he knew about the preparations of the terrorist attack, denying any prior knowledge of the bombing’s designated location, i.e. inside the Turkish border, according to the results of the interrogation.

Although Nazik is not the first or the last person to flee to Syria escaping legal and security charges, the source of controversy was that the Syrian regime had purposefully avoided mentioning the incident, especially since the operation took place in the regime’s largest stronghold. Thus, Yusuf Nazik admitted to plan the bombing in cooperation with the regime’s intelligence services and for the interest of al-Assad.

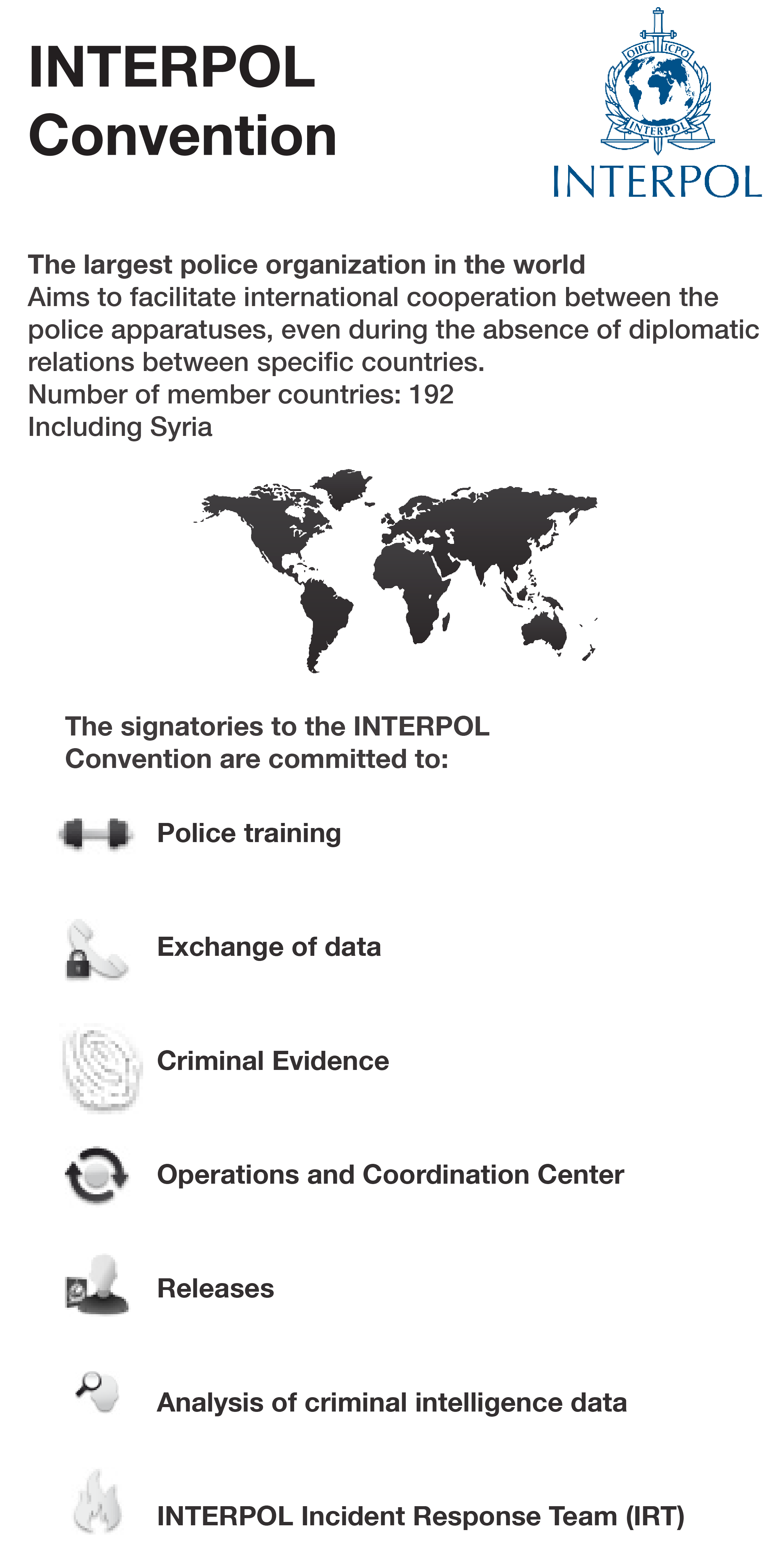

Syrian lawyer Yasser al-Sayyed, an expert in criminal and military courts in Syria, said in an interview with Enab Baladi that Syria had signed an agreement with the Interpol and that the Syrian authorities are supposed to abide by the terms of this accord.

But, what happened in the case of Nazik is that the Syrian regime did not acknowledge the suspect’s presence in the Syrian territories, “which is contrary to the provisions of the agreement” according to al-Sayeed.

Lebanon’s lord of drug trafficking circulates freely in Syria

A member of al-Assad family in Syria, Wassim Badie al-Assad, posted his photos with Noah Zaiter, the notorious Lebanese drug trafficker, on his Facebook page last June. However, the photographs were not taken in Lebanon but rather in Homs, Syria.

Although Zaiter has been speaking out of committing many crimes, including drug trafficking and cultivation, and admitting that he is wanted for justice, the photos that Waseem al-Assad published did not trigger the Syrian authorities.

Noah Zaiter is one of the most dangerous wanted people by the Lebanese security forces because of committing hundreds of crimes, including cannabis and drug dealing. The mayor of Baalbek, Hussein al-Lakis, said in an interview with the Saudi newspaper Asharq al-Awsat last June that a number of those wanted by the Lebanese judiciary had fled to Syria, after the Lebanese army talked about carrying out a security plan in Baalbek to arrest them.

He added that the wanted persons fled to tourist resorts in the coastal city of Tartus, and pointed out that security coordination between Lebanon and Syria would lead to their arrest.

The crime of Kuwait… hidden behind a local constitution

In February 2018, the Kuwaiti authorities found the dead body of a Filipina housemaid inside a refrigerator in an abandoned apartment in Salmiya neighborhood in Kuwait City. Investigations revealed later that the perpetrators were a Lebanese man and his Syrian wife, and that the dead body remained in the refrigerator for a year and a half before finding it.

During that period, the couple went to Syria immediately after committing the crime, while the Criminal Court of Kuwait had filed an in absentia death penalty by hanging against them in last April.

However, after Interpol circulated the names of the two accused persons, the Syrian authorities arrested them and handed over the Lebanese husband to his country’s authorities, while his wife, who has not been sentenced to date, was held in custody.

During the investigation, the accused husband confessed committing the crime, pointing out that his wife tortured the housemaid and he put her in the refrigerator, though she was still alive, according to forensic report.

The Lebanese authorities refused to extradite the accused husband to Kuwait, as the Lebanese judiciary refuses external parties’ trial of its citizens.

The Syrian constitution also prevents the extradition of Syrian citizens to foreign authorities to be tried in their courts or to be penalized under a decree issued by a foreign judiciary, under Article 38 of the Syrian Constitution.

The regime turns Syria into a tax haven

Syria has not only been a haven for people who committed crimes in their home countries, but the regime has also attracted businessmen who were described as “corrupt” through turning Syria into a safe haven and enacting special laws related to economic and tax policy.

A safe tax haven is a country that charges low taxes or does not impose any taxes, has its own fiscal and tax policy, banking regulations and laws, and deals following the principle of complete confidentiality regarding the identities of its registered companies, their owners or customer accounts, thus protecting them from prosecution.

The country, which is considered a tax haven, refuses to cooperate with the international organizations concerned with tax prosecution of people. The country also refuses to cooperate with judicial authorities in other countries, making it attractive to rich people and businessmen.

Strong banking structure is the first step

The country that is a tax haven is characterized by financial openness and the non-imposition of legal restrictions on the entry and exit of funds. Therefore, it is necessary to build a banking system that facilitates and expedites administrative procedures. This is what the Syrian regime is working on, according to economic analyst Younes al-Karim.

Al-Karim added in an interview with Enab Baladi that “in order to have a tax system, there is a need for an advanced banking structure to facilitate the entry and exit of funds.” This was provided by the former Governor of the Central Bank of Syria, Adib Mayaleh, through the “e-government” system in its monetary form, in a way that all banking procedures between customers and banks are carried out online, like developed countries.

According to al-Karim, Mayaleh had also worked on developing the bank’s infrastructure by linking banks with the so-called Electronic Clearing Service (ECS), which refers to the transfer between banks through an electronic network operating with the ERP system that connects the banks with each other in an integrated database, in a way the Central Bank becomes an observer of all financial transactions.

In November 2012, the state-owned al-Thawra newspaper said that “the bank has started the procedures of implementing the electronic clearing project for the purpose of collecting checks, and is adopting the transfer of the electronic image of the check between banks instead of conventional methods, which expedites and facilitates the process of collection and settlement between banks in a safe, easy and fast way.”

Since his accession to his position in 2016, the former Governor of the Central Bank of Syria, Duraid Durgam, had paid great attention to the electronic clearing project and considered that its development will reduce the circulation of banknotes, reduce the factors of the manipulation of the exchange rate and speculation, and allow the rapid transfer of funds between banks with the aim of encouraging deposit, a better control of liquidity and the development of more precise and effective policies.

According to al-Thawra newspaper, Durgam said in December 2017 that the most important part of the structure of the electronic environment will be available for the public soon, including e-portfolio management and clearing operations. He also pointed out that an electronic payment system is currently being prepared, which the system is seeking to implement in purchasing and selling operations.

Attracting investors through a lavish infrastructure

In addition to an advanced banking system, it is necessary to provide businessmen with an infrastructure that comprises luxurious hotels and apartments. This will encourage wealthy people to travel to Syria and businessmen to invest their illicit funds, which they have earned through the drugs smuggled or the goods stolen from their state institutions, to purchase and sell real estate. These business activities will be lucrative in Syria due to the high prices of these estates, and therefore these funds will be reproduced into legitimate funds thanks to the existing strong banking structure, according to Karim.

For this reason, the Syrian regime is working to establish residential cities near Damascus, such as Marota and Basilia Cities. However these cities will not be reserved for the Syrians, but rather for the Arab and foreign people belonging to the wealthy classes who have no problem in carrying out suspicious and illegal deals, especially with the international sanctions imposed on al-Assad. These projects are expected to attract “gangs, mafia and corrupt leaders” in the world and become a safe shelter for their money, and in return the regime will receive their financial and logistical support as well as a share of these funds.

“Damascus won’t be an industrial city at all, but a residential city where people can relax and live,” stressed the member of the executive office of Budget and Financial Affairs, Faysal Suroor, during a seminar held last March.

Karim stated that Syria was chosen because of its strategic location and for being a promising market due to its ability to attract too many investors and establish many projects, such as building infrastructure. The regime is trying to rearrange its economic and political documents and strengthen its authority in Damascus by turning it into a safe tax haven.

Dubai, UAE, which is considered as a tax haven in the region, is no longer able to receive and attract investors because it is at capacity. In addition, Damascus is the Gulf’s gateway to the Mediterranean.

Counter escape… running away from accountability

Unlike regime-held areas, which have been turned into a shelter for wanted people, the unofficial status of the courts in opposition-held areas prevented them from prosecuting perpetrators of crimes or those convicted of committing different charges and have left their areas to Turkey or to regime-held areas.

Several incidents where prisoners run from some prisons without being prosecuted have occurred repeatedly. The city of Bab al-Reef in eastern Aleppo countryside had witnessed a security alert last September against the backdrop of prisoners’ mass escape from the military police prison.

Enab Baladi’s reporter in Aleppo countryside stated that the number of prisoners who escaped amounted to 13, but the military police managed to arrest eight of them.

It was not the first time that prisoners escape from the prisons of the Free Syrian Army’s factions. Previously, 180 prisoners managed to flee the Central Prison of Idlib, held by Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham, to unknown destinations in Idlib Governorate last August.

In July, 17 members of ISIS escaped from a prison of Sham Legion (Faylaq al-Sham) in the countryside of Afrin.

Last May, 28 prisoners belonging to ISIS escaped the prisons of Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham after they managed to smash a window at the top of the wall in the town of Binnish in the countryside of Idlib.

Lawyer Yasser al-Sayed, a specialist in criminal cases, noted in an interview with Enab Baladi that “courts in areas that are not held by the regime are not acknowledged by the international community, and therefore people sentenced from local courts there are able to escape punishment.”

Al-Sayed stated that arresting these people “will be difficult, or rather impossible,” because Interpol will not be responsible in this case, since these people have not been sentenced by an acknowledged court, such as the regime’s.

According to al-Sayed, this is the most serious case, for many criminals are now integrating themselves into other communities and posing great threat to them. He recalls the bombing of the central prison in Idlib in 2015, which has been also reached the court, where some people were sentenced to death.

“These people fled to Turkey and lived there, because there was no internationally acknowledged court that could send a file to Interpol or circulate the name of the wanted person at the borders. Some of them committed murder or embezzlement, raised huge sums of money by investing them and escaped with all of the money they earned,” he said.

Opposition factions-held areas are governed by different laws, according to the ruling faction. The courts vary, and this would give a great chance for criminals to escape from justice.

Criminals Extradition in international law

Extradition is defined as the procedure by which a state would extradite a wanted person to another state for trial or for the imposition of a penal sentence by its courts.

Extradition is carried out either on the basis of international agreement or reciprocity, and it is a necessary for the principle of solidarity among states in the fight against crime so that the sovereignty of states is not an encouraging cause for committing crimes.

Thus, the fugitive finds a safe haven in some states that do not abide by treaties or do not apply the principle of reciprocity, in addition to the difference of the content of those treaties from one State to another.

In principle, all persons who are refugees to the territory of the state may be extradited, but international custom came with exceptions, namely, that the state does not extradite its nationals, people who appeared in court, and diplomatic or consular corps.

Among cases of extradition between states, international custom excludes cases where the crime is prohibited by law or custom, such as political and military crimes.

Extradition in Syrian law

“Extradition and Prosecuted Persons Law” No. 53 of 1955 provides for the implementation of the principle of extradition in Syria. Article 1 states: “In the absence of international treaties which have the force of law in Syria, the provisions, principles and effects of ordinary criminals’ extradition and people who are prosecuted for ordinary crimes shall be subject to the provisions of this Law and Articles 30 to 36 of the Penal Code.”

The Syrian authorities follow the mixed (administrative-judicial) method of extradition, albeit in a predominantly judicial manner.

The state that requests extradition shall apply to the Syrian authorities by diplomatic means. Then, the request is submitted to a committee in the Ministry of Justice called the Extradition Committee. This body examines the request from both sides. The first one is formal, where it examines the availability of the legal conditions of the demand, such as that the person sought for extradition is a non-citizen, the crime shall be non-political, or the imprisonment penalty provided for the crime shall not be less than a year, in accordance with article 33 of the Penal Code.

The other aspect where a request for the extradition of a criminal is being considered is the objective dimension. The Extradition Committee has the right to examine the basis and the facts of the case to determine whether the charge is proven. This committee is composed of two judges, headed by the assistant to the Minister. It can arrest and interrogate the accused and carry out all legal acts that it deems necessary to reach the truth, and then issues its decision to extradite or reject the demand. This decision is concluded, and no method of review is accepted.

If the committee decides to reject the extradition request, its decision shall be binding on the executive authorities and shall they refrain from extradition in accordance with article 35, paragraph 1, of the Penal Code.

However, if the decision is to accept the extradition request, it is not binding on the executive authority, which is free to implement it or not. In all cases, the decision of extradition is effective only if it is issued by a decree.

Penal code and extradition

The extradition condition was mentioned in the Syrian Penal Code in Article 30, which states that “no one shall be extradited to a foreign state, except in cases provided for in the provisions of this Act, apart from being an implementation of a treaty which has the force of law.”

This means that Syrian law does not apply the principle of extraditing from Syria to other countries, as stated in the Syrian Penal Code in Article 32 thereof.

Some of the extradition agreements between Syria and Arab states included the fact that “the requested state may refuse to extradite a person in case he is a national.”

In addition, the person sought for extradition is considered Syrian, in case he holds another nationality (Even if it is the nationality of the state that demands extradition) and he has a Syrian nationality. He is excluded from the extradition according to the Ministry of Justice’s letter No. 3749, which imposes the treatment of a citizen who holds several nationalities in addition to Syrian citizenship as a Syrian citizen.

Further, the extradition demand is rejected if there is a lawsuit against the person sought for extradition before the Syrian courts, and this was confirmed by Article (33) of the Penal Code, paragraph (3). Extradition demand is rejected under the same article if the Syrian law does not punish the crime with a criminal offence or misdemeanor. However, the opposite happens if the circumstances of the offence are not available in Syria because of its geographical situation.

The demand is also rejected if the penalty provided for in the law of the state that demands extradition or the law of the state in whose territory the acts were committed does not amount to one year in prison for all the offences dealt with in the demand. In the case of the sentence, the penalty cannot be less than two months in prison.

The same thing happens if a sentence was issued on the crime in Syria, or the case of the public right or punishment was dropped in accordance with the Syrian law or the law of the state demanding extradition, or the law of the state in which the crime was committed.

Meanwhile the Syrian Penal Code is consistent with international law in excluding political crime from extradition. Article 34 states that “an extradition demand is refused if an offence is of a political nature or appears to have a political purpose.”

if you think the article contain wrong information or you have additional details Send Correction

النسخة العربية من المقال

-

Follow us :

A soldier in al-Assad forces waving a flag and a machine gun after Israeli raids targeted Damascus - April 14, 2018 (Reuters)

A soldier in al-Assad forces waving a flag and a machine gun after Israeli raids targeted Damascus - April 14, 2018 (Reuters)

A

A

A

A

A

A

More In-Depth

More In-Depth