Syrian women have never been absent from the workplace alongside men. However, this issue has received varying levels of attention and acceptance according to the historical context and the economic and educational situation in the country. After the Syrian revolution, the security situation in the areas controlled by opposition factions, continuous shelling and poor economic conditions have resulted in the restriction and decline of women’s role in this respect.

Although there are many civil society organizations whose programs carry ideas that promote the role of women and enhance their contribution and role in society, this role has not progressed significantly, and has even witnessed a relative decline. This is linked to widespread “conservative” thinking in most of these areas, as well as shrinking opportunities and the need for specific occupations through which women can support their families.

While most doctors and teachers are still working in their field, a broad range of educated and specialized women in various fields (law, engineering, economics, applied sciences) have lost the opportunity to work in their fields of study, and most have switched to teaching or other professions.

Between the difficult and the forbidden

Syrian women keep their jobs despite the war

Doctor Ikram speaks quickly while often stopping to catch her breath, telling us about the exhausting conditions she has to endure. The dark bags under her eyes tell the story of her city, which only recently gained freedom, paying with the lives of its people and their bodies and endless worries. A small movement on the ultrasound display pushes her to continue working, burdened with responsibilities that do not end by the end of the day, and which she feels she cannot carry out to the best standard.

Enab Baladi interviewed Doctor Ikram Habboush in her small clinic in a medical complex in Idlib, after several failed attempts due to lack of time and the large number of female patients at the clinic. It is natural that Doctor Ikram has no time to talk about the difficulties of her work or about anything other than a due date, the need for a caesarean section or the uncertain future of a child without a father.

“We are responsible for people’s lives. There is no room for error in our work, and this increases the pressure on us”, says the doctor, who has had several responsibilities from an early age. Despite being a recent graduate, a wife and mother of several children, she found herself facing a professional “duty” that she is obliged to fulfill, while at the same time facing a society which ambuscade women, and a family that requires care and attention.

While most women in the city of Idlib, where society is still relatively conservative, want to visit a female doctor for examinations, only four women doctors – including Ikram – are still working in defiance of the conditions of bombing and displacement, and a society that, although it is not completely opposed to women working, does not want women to be away from their homes for long periods of time.

We all know the saying, “a woman is half the society”. According to statistics indicating a decline in the number of males in comparison to females, women now represent more than half the population in Syrian areas controlled by opposition factions. This often occurs during wars, a time when women’s influence and contribution often increase. German women are credited with rebuilding Germany after the Second World War, paving the way for a country with solid institutional foundations and a strong economy.

In Syria, however, despite many efforts to strengthen the role of women, it continue to be below the level expected. According to the president of Idlib city council Ismail Andani, women are reluctant to participate in many roles, both at the professional level and at the administrative and governmental levels.

Pragmatically speaking, Syrian society is drawing on women to meet practical needs while depriving them of a large portion of their interests and ambitions in the areas controlled by the opposition. While a proportion of workers in the medical field still practice their profession (as doctors, pharmacists, nurses), the majority of engineers and graduates of specialized branches (such as economics, natural sciences and engineering) have switched to teaching, as confirmed by Idlib’s health manager, Doctor Mundhir Khalil. He points out that women make up 30% of workers in the health sector. While this percentage is considered “good”, it exceeds many times the scale of women’s participation in other sectors.

From the point of view of Doctor Ikram and other women who have decided to work despite war and living in a society full of restrictions, “social pragmatism” opens the door for women from one of side while closing it from another.. The restrictions they face do not seem worth stopping work for, even though they represent an additional burden. Doctor Ikram says that motivation is what makes her resist her desire to stop working, but her love for the experience and belief in the necessity of giving push her to increase her workload and contribute to establishing a charity for orphans as well.

Other women who managed to circumvent this exploitation and adapt themselves to the general needs of society in order to achieve their goals. Hala al-Shami, an engineer, was able to join the projects and planning section of one of the local councils in Eastern al-Ghouta after having been forced to work in teaching for around four years, without losing her dream of going back to engineering. She says she pays no attention to “men’s awkward looks” that seem to ask, “What is a girl doing here?”.

Hala believes that being a girl who works in a predominantly male workplace requires having a strong personality to be able to face having the projects she proposes repeatedly rejected and having her work devalued “just because she is a girl”. This necessarily leads women to rethink their decision and makes the idea of work itself “arduous”.

The war has exhausted Syrian women, with some choosing a life of homelessness and displacement, while others face a life where they have no power to decide their fate. However, it has provided a very limited opening for some women who want to work in fields that had just begun to go beyond male domination at the end of the last century, and which are once again being monopolized by men after the start of the Syrian revolution.

“May God help working and non-working women,” says Dr. Ikram Habboush, with a long sigh that carries the intermingled fatigue of a mother and a working woman. It is clear that the daily problems women suffer in liberated Syrian territory amount to a struggle, under the gaze of a society plagued by war and that is still scrutinizing women’s every move.

Apparent presence and absence from specialized fields

How has women’s labour participation in Syrian opposition-controlled areas changed?

Syrian women have found an opportunity to strengthen their role in economic life during the ongoing conflict since 2011, assisted by the deterioration of the economic situation in the country and the massive waves of displacement that have disrupted customs and traditions in the areas of origin of Syrians.

Regardless of whether they are forced to work to support their families or driven by the idea of empowering women in Syrian society, economic life has witnessed a remarkable growth in women’s active participation, as advocated for by Syrian women’s organizations for years under the term “gender”.

Women’s work depends on the presence of organizations

Local relief associations and civil society organizations have been active during the recent years of war and displacement, providing both moral and financial support to those who have been affected by the conflict in various parts of Syria and who lack basic necessities.

In order to prove their ability to meet the pressing needs of society, Syrian women have become involved in working for these associations, which now require female candidates to hold a university degree for some positions.

This data reveals that civil society organizations operate not only in regime-controlled areas but also in liberated areas controlled by the opposition. The total number of these organizations, which are providing health care, social and educational services, has reached more than 1000. 91% of these organizations became active after 2011, according to statistics provided by the organization Citizens for Syria, which focuses on the work of Syrian associations.

According to the study “Syrian civil society organizations: reality and challenges” carried out by Citizens for Syria, 44% of organizations operate in opposition-controlled areas, which represents the largest proportion when compared with all other regions.

Organizations operating outside Syria are ranked second (23% of organizations), followed by 14% that operate in government-controlled areas. The remaining organizations operate in the Kurdish areas of “autonomous administration”.

Thus, civil society organizations have broken the monopoly held by the provinces of Damascus and Aleppo and have spread throughout all Syria’s provinces except for Raqqa and Deir Ez-Zour, which are under the control of ISIS.

Is women’s role being strengthened or limited?

According to Citizens for Syria’s data, more than 25% of organizations that are operating target women as a “vulnerable” group in society. Thus, most of their employees are women. as women are more able to delve into private social life and to interact with women and children.

However, in other organizations, women’s employment opportunities are the same as men’s, despite their absence in strategic and leadership decision-making roles at a rate of 88%, according to a study carried out by “I and She” organization in March 2016.

As for women’s participation in liberated areas, many organizations, including Rakeen, which focuses its work on women and children in Idlib, told Enab Baladi that most of the women working in these areas are involved mainly in relief organizations and associations as well as working as teachers and nurses. Opposition-held areas have a real shortage of female specialists in medicine, engineering, IT, accounting and other disciplines and official positions, which reflects the gap of genderization.

Restrictions still in place and women “need to do more”

Ismael Andani, the head of Idlib city council, told Enab Baladi that women are notably absent from political life in the areas controlled by the opposition, as well as from specialized professions such as medicine, accounting and engineering.

He said, “Both women and official authorities need to do more. We need female specialists. We need female doctors, engineers and teachers. However, there are certain moral and religious constraints and regulations that apply.”

Andani explained that the city council opened the door for women to participate in the council’s founding elections, which were held last January. However, women “refrained” from standing as candidates and from voting, amid the absence of encouragement for them to engage in political life.

He explained that in the aftermath of the elections, Idlib city council introduced a new office called the “Office for Assistance to Women” in order to promote the role of women and to represent them in the council’s departments and institutions.

Despite the “limited” openness to women working in liberated areas, customs and traditions still constrain their ability enter more specialized fields and to take decision-making roles.

Nada Samee, director of the organization Barqet Amal, which focuses on women’s affairs in Idlib, says that women in the liberated areas “have to work in all fields but within the prevailing customs and traditions and the framework of religious and moral codes”.

“The civilized woman” in the eyes of the regime

In its attempt to convey a civilized image of its areas of dominance, the Syrian regime has opened new opportunities for women to work. The regime has made different roles in social and political life accessible, appointing Hadia Khalaf Abbas as head of the People’s Assembly making her the first female head of parliament in Syria’s history.

Due to security conditions, women have entered professions previously restricted to men, such as working in restaurants, selling from food carts and specialized administrative and official occupations.

The current situation in Syria has seen the proportion of females increase to reach 65% of the total population. Companies and institutions are keen to stabilize their own situations by recruiting women instead of men in order to avoid having their employees called up for national service (which is obligatory on males), which leads to young men either travelling abroad or enrolling in the army.

In spite of all this, a large proportion of women in regime-held areas work as teachers. The results of a competition to select teachers run by the Faculty of Education showed women to be far outperforming men, revealing the large numbers of women entering the teaching profession. 89% of the graduates from the teachers’ college specializing in primary school level were from Damascus while 85% of the teachers were from the province of Homs, according to data from the Ministry of Higher Education.

Exceptions highlight the “limited” role of women

Syrian women in the liberated areas also enjoy prominent leading roles. The appointment of Bayan Rehan as the head of the Women’s Office by the local council of Duma is a perfect example. The council’s initiative was the first of its kind compared to local councils in other regions.

Rehan told Enab Baladi that the work of women in the liberated areas has not diminished but has been “concentrated” in specific areas, namely the educational, medical and NGO sectors, while they play no “effective” role whatsoever in political life.

She added that the work of women in al-Ghouta “has been restricted to the field of teaching”, with “even graduates of the Faculty of Commerce and Economics working as schoolteachers.”

Rehan attributed the absence of women from political life to their lack of qualifications in this field and their inability to break the rules that prevent them from working in official positions.

Women have also had a prominent role in the media since the outbreak of the Syrian revolution. Many female journalists have appeared in liberated areas, who have gained a large following among women, according to Sawsan al-Saeed, a board member of Barqet Amal who spoke to Enab Baladi. “There are many female journalists who have been entered the media sector, many more than males, because they are more able to delve into the hidden aspects of social life.”

The Syrian Civil Defense Force team (White Helmets Commission) has also witnessed the participation of women in the fields of nursing and medical assistance. The number of female volunteers in the liberated areas has reached around 200 out of 3000 volunteers, which amounts to 6.6% of the total number of volunteers.

Gender

The term “gender” refers to the relationships, social roles and values defined by society for both sexes (men and women). These roles, relationships and values change according to space and time due to their intersection with other social relationships such as religion, social class, race and others.

“Gender” is a relatively recent concept, emerging in the 1980s as a prominent term used in feminist vocabulary, first in North America and then in Western Europe in 1988.

“Gender” differs from the concept of equality between women and men. In fact, it aims at enhancing the role of women in proportion to their potential and their ability to contribute to a particular area and to be present in a particular place, and not to create competition over roles between women and men.

In accordance with the 1979 Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), “genderization” calls for changing the social and cultural behavioral patterns of men and women in order to eliminate prejudices, customary practices and all other practices that are based on the belief that either sex is inferior or superior to the other, or on stereotyped roles for men and women.

It also refers to the need to adjust the social and cultural behavioral patterns of men and women with a view to achieving the elimination of prejudices, customary practices and all other practices that are based on the idea of inferiority or superiority of either sex or stereotyped roles of men and women.

In Syria, the term “gender” or “genderization” has only recently begun to be used. Its spread can be linked to the increasing number of local and international civil society organizations that have increased after the Syrian revolution.

The prevalence of the term has also been linked to the need to strengthen the role of women in light of the deteriorating security situation in Syria and the tendency of some regions to adopt forms of religious extremism that prevent women from participating in various social roles, and different working conditions, in addition to the need to enable them to make a greater social contribution in the post-war phase.

46% say there is a lack of job opportunities for Syrian women

How do civilians in Syria view the idea of women working?

In opposition-controlled areas in Syria, there is a widely-held view that there has been a decline in job opportunities for women. There main difference is between supporters of the principle of women working and its opponents, based on various arguments. There are varying views over the professions in which women should be able to work and make a contribution.

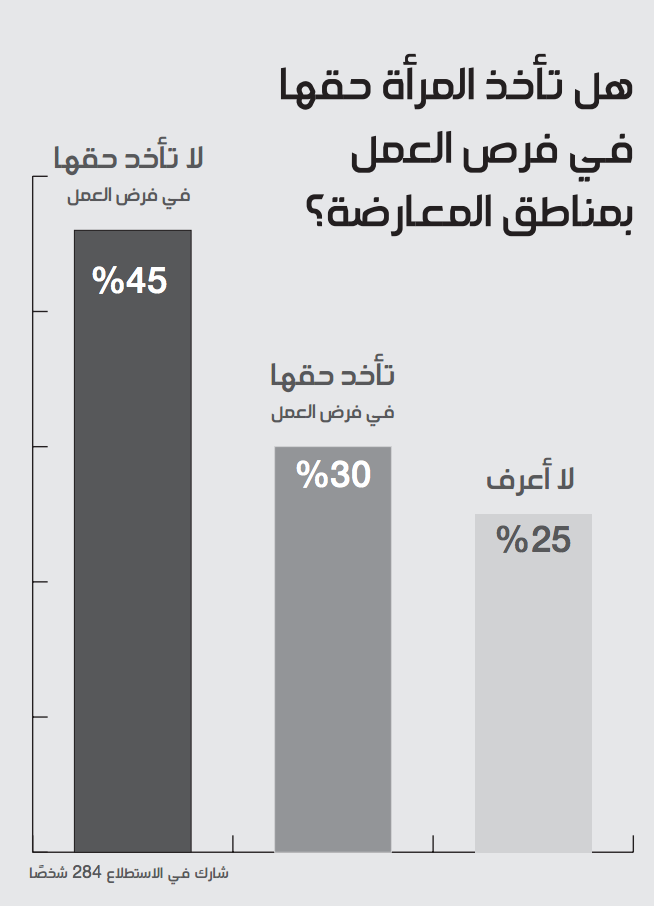

In a poll conducted by Enab Baladi on its website, it was revealed that most of the 170 participants believe that women in opposition-controlled areas do not enjoy enough job opportunities, while 29% believe that they do.

Enab Baladi also conducted a video reportage with a number of civilians from different professions and specializations concerning employment opportunities and whether there had been a change after the outbreak of the Syrian revolution. We also touched on the most important obstacles to women’s labour participation and the jobs that still attract the largest number of female workers.

Before and after the revolution

Most respondents believe that job opportunities have declined significantly after the outbreak of the Syrian revolution, compared with the years before 2011, which had witnessed a relative recovery in the labor market and a diversification of opportunities, both in the private and public sectors.

Yahya Nema, a pharmacist from Idlib, believes that employment opportunities for women have declined because of the circumstances following the revolution, including shelling and the dangers faced by women as a result of the difficult security situation during the war.

Nermin Khalifa, the director of the Union of Educated Women in Idlib, attributed the decline in women’s employment opportunities compared to the period before the revolution to the disappearance of institutions and directorates that used to provide a suitable place for working women specializing in various fields, stressing that “the destruction of institutional infrastructure” has strongly affected women’s ability to work.

Urf (custom) and Sharia regulations

Amin Badran, an engineer residing in Eastern al-Ghouta, says that urf (social customs) are what determine the nature of jobs that women can do, by accepting certain types of work and refusing others.

Ridha Samee, director of the Education Office at the organization Barqet Amal in Idlib, points out that women can work in all fields as long as she respects “Sharia regulations”. “A female engineer can work in places where she does not have to mix with men. She can improve her house by linking it to the electricity supply”.

Doctor or teacher

Judge Rateb al-Riz, who lives in Eastern al-Ghouta, explained to Enab Baladi that women no longer work as lawyers in opposition-held areas, nor are there any female judges in those areas. He pointed out that he supports this, since women must work in the field of medicine or education but not in the judiciary, arguing that “a nation with a female ruler will never be successful”.

Yahya Nema, a pharmacist Enab Baladi spoke to, believes that efforts by women to enter into the institutional field is still “limited”, while the role of women in the medical field is almost equal to that of men.

Lack of “political maturity and knowledge” restricts women’s participation

Interview with the former Minister of Culture and Family in the interim government, Samah Hadaya

Former Minister of Culture and Family in the interim government, Samah Hadaya, described the work of women in liberated areas as “superficial participation”. In an interview with Enab Baladi, she said that women in these areas are able to take control and play a leading role but “she is never involved in the decision-making process”.

Although she emphasizes the importance of the role played by women in the health, educational and organizational sectors, she refuses to confine and restrict this role to sectors other than specialized field, “If women do not participate as leaders in the workplace, their work will remain superficial”.

Same mentality prevails among leaders

Hadaya criticizes the leaders responsible for civic and social life in opposition-held areas, describing them as “backward and undeveloped”. She considers that those leaders have not allowed women to undertake “real and effective” work that matches their abilities and qualifications.

Most of the organizations that Enab Baladi met in Idlib and al-Ghouta pointed out the presence of university graduates working in fields other than their specialties. Among these is Wisam Maari, the director of Rakeen’s office for orphans. She is a civil engineering graduate but did not find a job in her area of specialty. So, she joined the organization.

Former minister, Samah Hadaya, called for placing Syrian women in the position they deserve according to their specialization and qualifications, far from the customs and traditions imposed by leaders in opposition areas, as she put it.

“Protecting women intellectually before protecting them physically”

Samah considers the first solution to promoting the active role of women in opposition areas to be “the involvement of women in official women’s associations that have the mission of leading the process of effective, not superficial, change”.

She also called on the ruling civilian leadership to adopt a “mature” mentality and a political framework that believes in the work of women and gives all social groups their rights within the framework of social justice.

She also called for activating the role of female intellectuals who are capable of taking control. She added, “We must develop the skills of women in specialist fields and train them to work in their own sectors in order to be able to participate effectively in political, social and administrative life”.

As for raising awareness among women, Hadaya stressed the importance of using techniques that are far from the “gender awareness” approach that has become more of a threat to women than a way of protecting them. She argued that it is important to protect women “mentally and intellectually before protecting them physically” and activating their leadership role in a society that has been “destroyed”.

if you think the article contain wrong information or you have additional details Send Correction

النسخة العربية من المقال

-

Follow us :

A

A

A

A

A

A

More In-Depth

More In-Depth