Enab Baladi – Jawad Sharbaji

“You have come to your final resting place. This is hell. God does not enter on the orders of President Hafez al-Assad, so do not bother praying to anyone!”

This is how the official welcoming rituals begin for those arriving at the prison in the middle of the desert, according to Ali Abu Dahan, a Lebanese national who was formerly detained in Tadmur prison. Abu Dahan recounted his experiences at the opening session of the “Documenting Darkness” conference held in Bern on 12-14 December 2016.

Faraj Bayrakdar, Ali Abu Dahan, Baraa al-Saraj, Mohammad Berou and Wael al-Sawah are five former detainees who were all held in Tadmur. They came to Bern from different countries at the invitation of Umam Foundation for Research and Documentation and Etana to discuss the issue of prisons in Syria over the course of the two-day conference. They shared with attendees their personal stories of life in Tadmur prison and it was clear that its effects had yet to be erased from their souls or bodies.

Abu Dahan is the head of the Association of Lebanese Detainees in Syria. He still speaks in a hoarse voice after being forced to swallow a dead bird, damaging his vocal cords. He said that he would “never” forget what he experienced in Tadmur prison even 16 years after leaving it, and that everything he experienced is etched in his memory “like engraving in stone.”

According to Abu Dahan, enumerating the different methods of torture is no longer that important as they are the same in every place ruled by a torturer. The methods do not differ according to nationality, belonging or alleged crime. The important thing is for detainees to break the taboo about their experiences in Syrian prisons, which kept detainees silent during the years of iron rule, regardless of their nationalities, according to Abu Dahan.

The former detainee is one of 782 Lebanese nationals whose detention in Syrian prisons Umam has documented. “What we witnessed, experienced and is imprinted in our memory, what you are seeing today in the horrific images of detainees who died of starvation or due to their reproductive organs or tongues being cut out, is the same thing we will continue to witness today and tomorrow – torture, terror and terrorism, killing, blood and crimes unless the United Nations, major powers and non-governmental human rights organizations do something to stop these daily inhumane violations of the rights of Syrian, Lebanese and other prisoners held in all Syrian regime prisons,” said Abu Dahan, summing up his experience of 13 years spent in “hell.”

Mohammad Berou was arrested at the age of 17 in May 1980 and accused of joining the military youth wing of the Muslim Brotherhood. He was not executed at the time as he was still a minor but was instead sentenced to 10 years imprisonment, which was then extended to 13 years. He was transferred to Tadmur prison where he spent 12 years, witnessing the most brutal period of torture and field executions ordered by Hafez al-Assad.

Berou quotes the hero of the film “Imagining Argentina”, which tells the story of forced disappearances in Argentina – “The survivors never forget…what is left if we forget? Our lives are just past memories, and if they finish or are lost, nothing will remain.”

Storytelling is a form of resistance where the regime seeks to hide the truth. Documenting these experiences restores value to the victims, even if it cannot restore their rights. It immortalizes them in the national and social memory, as well as identifying the criminal and condemning him, according to Berou.

In Berou’s opinion, the value of documentation lies in the extensive number of witnesses, victims and survivors who have lived the Syrian crisis since the 1980s and who are now recounting their stories and giving their testimonies regarding the violations and injustices they experienced, to identify the perpetrators and condemn them, which is the least that could be done to achieve justice.

According to Berou, Tadmur was the site for the execution of over 15,000 detainees, and all were executed without a single written order from the President. Most of the orders were verbal, as the regime recognized early on that documents and written orders may serve to condemn it later on in any trials or inquires that might ensue. The lack of execution orders is one of the greatest challenges to documenting crimes in Syria.

Tadmur prison was built in 1966 close to the desert city of Palmyra (Tadmur) with its famous archeological sites. It was intended to be for members of the military in particular but during the reign of al-Assad (the father and son) the Syrian regime used it for detaining prominent political and opposition figures. Amnesty International described the prison as “designed to inflict the greatest possible suffering, humiliation and fear on inmates.”

My land “blessed” me with countless lashes that only God could count. The number of lashes I received almost equal the number of words I have written; can you believe that? This is what Faraj Bayrakdar, a Syrian poet and politician, said while describing his experience in Tadmur and Sadnaya prisons. Bayrakdar was detained three times during the reign of al-Assad senior, and was held for 14 years in his last period of detention.

Bayrakdar said that with the passage of time and after repeated slaps, curses and beatings, he learnt to present himself as “Prisoner number 13”. Prison is an attempt to destroy the inmate’s sense of value, “So I had a deep conviction that any creativity or act to create meaning through writing or art or even gossiping was a mode of challenging prison and its effects… Poetry managed to save me and give my life in prison a different meaning or different value than what was desired for me.” Prisoner number 13 left prison having written six poetry anthologies and a story about the prison experience and its most significant incidents.

Tadmur… Our Prison… Our Home… And the Keeper of Our Secrets

On 30 May 2015, “Daesh” blew up Tadmur prison, days after they gained control of the city of Tadmur in Homs’ eastern countryside. The prison’s tale ended there after having borne witness to the many massacres perpetrated against its inmates in the 1980s and during the Syrian revolution.

Ali Abu Dahan said, “When Tadmur prison was destroyed people rejoiced, but my colleagues and I who were in Tadmur cried… we cried over our prison, our home, the keeper of our secrets… We cried over the walls that we leaned on and used to tell our stories to, which heard our pain… We cried over the ground that drank from our blood and our feet…that drank our pain… We cried over the military blankets that we used to cover ourselves with, which were covered in blood and rust after so many years… We cried over the scabies that we carried, the disease and the pains that we lived in Tadmur… We cried over Tadmur prison, the place that should have remained a museum for people to know what happened inside it.”

Activists and Politicians Discuss the Issue of Prisons in Syria

Participants at the conference “Documenting Darkness” in Switzerland, 14 December 2016 (Enab Baladi)

The Syrian organization “Etana” and the Lebanese organization “Umam Foundation for Research and Documentation” held a conference on the issue of prisons in Syria in the Swiss city of Bern on 12-14 December 2016. The conference was supported by the German Institute for International Affairs and the Human Security Division of the Swiss Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Around 20 activists and politicians from Syria and Lebanon, representing various human rights, research and media organizations, attended the two-day conference to discuss the various dimensions of Syrian prisons. The conference saw several discussions and interventions that highlighted the reality of human rights and legal violations that detainees in Syrian prisons experience and the ongoing efforts to achieve justice in Syria.

The conference opened with testimonies of former detainees held in Syrian regime prisons, among them Faraj Bayrakdar, Ali Abu Dahan, Baraa al-Saraj and Basema Jabri. They spoke of their prison experiences and recounted some stories of their daily lives in detention.

The conference focused on the political dimensions of prisons in Syria through the presentation of Wael al-Sawah, manager of the Center for Freedom of Expression in Berlin and Radwan Ziyadeh, manager of the Syrian Center for Political Studies and Research in Washington. Both spoke about the history of detention in Syria and how the situation reached its current condition.

One session focused specifically on documentation and media efforts in Syria and the role of legal and media institutions in advocating for detainees. The session included presentations by Awees al-Dabbash, coordinator of the Center for Justice and Accountability, Bassem al-Ahmad, manager of the organization “Syrians for Truth and Justice” and Jawad Sharbaji, editor-in-chief of Enab Baladi. Some participants criticized the “cautious” approach by Syrian media to defending the cause of detainees to local and international public opinion. Participants called on media and documentation institutions to unify their strategies and draw up a joint work plan to develop a “professional” approach that engages with public opinion and influences it.

Documentation and its role as a tool of transitional justice were a significant part of the discussions, and two sessions were dedicated to the issue. Manager of the Sada Center for Surveys Mohammad Berou, French journalist Gharanas Loukin, program manager for the organization “Next Day” Omar Shnan, and deputy manager of the Arab Reconciliation Initiative Salam al-Kawakibi all participated in these sessions.

The conference concluded with a showing of the two-hour long film “Tadmur” produced by Umam Foundation. The film showing was attended by a number of participants and many interested Swiss attendees. The film portrays the daily suffering of detainees in Tadmur prison through re-enactment by five Lebanese detainees who spent many years in Syrian prisons. Their testimonies and experiences contributed to preparation of the film, which was recorded in a building constructed specially to replicate the desert prison of Tadmur.

What is Next After the Conference?

Luqman Slim, Umam’s director, considers that a conference on the issue of prisons in Syria hosting honest and open discussions is an “achievement” and contributes to pushing western governments to pay more attention to the issue at a time when detainees are considered a secondary consideration on political agendas.

In Slim’s opinion, the conference was an important opportunity to conduct a series of meetings between the relevant institutions, producing many ideas worth pursuing. He expressed Umam’s interest in following up the conference’s outcomes, adding that the institution is working on a regional project on prisons and has begun initiating preliminary contact with other countries on this issue. Slim described the project as transcending Arab borders, especially as the discussion on transitional justice has become part of the public space in the Arab world.

Using the Law to Silence Opponents

Ibrahim Hussein, Secretary of the Supreme Council for Justice

Tyrannical rulers need not find an excuse to execute opponents or imprison them, as they control all the resources of the country. No one holds the tyrant accountable and no authority protects the people from him.

Despite this, a tyrant is at times forced to find legal cover for his actions especially vis-a-vis foreign organizations and countries that may criticize him or open cases of human rights violations against him or in his country.

In Syria, the totalitarian regime hastened to legitimize the dictatorship and its oppression by drawing on a series of laws that are used as mechanisms to silence anyone who dared to oppose it.

It is well-known in criminology and legal studies that legal texts must be written using precise and clear terminology that is not open to all interpretations, but the tyrant’s law is distinguished by the use of language that is flexible, ambiguous and includes broad and vague terms that could potentially apply to all acts and include any person.

The tyrant’s objective is to guarantee a wide margin for judicial authorities when examining cases and determining situations to which the law applies. The accused becomes a hostage of the judge’s disposition, which is usually determined by the authorities and the state’s security apparatus, as so-called “judicial authority” is made completely subservient to the tyrant and turned into one of his tools.

The Syrian dictatorial regime worked according to this principle. The articles of the penal code on crimes against state security, internal or external, are characterized by their generality and vagueness. The same characteristics are found in all the laws and decrees issued after the Baath Party took power.

Decree number 6 of 1964 punishes all who oppose the aims of the revolution and resist the implementation of the socialist system, whether verbally, in writing or other acts. Those who are accused based on this decree are punished with life imprisonment and in serious cases the sentence extends to capital punishment.

The text can be interpreted in many ways to include any action that displeases the authorities. This decree has been used extensively to justify the arrest and trial of persons opposing the regime.

Executive Decree number 4 of 1965 is similar and includes the following clause, “Any person who attempts to obstruct the execution of socialist legislation will be punished with a life sentence of hard labor, and the sentence may extend to execution.”

In addition to these decrees, several laws were used to justify arrests, among them Law 49 of 1981, which is an emergency law that mandates capital punishment for all persons belonging to the Muslim Brotherhood movement, even if the person did not commit any other crime. Perhaps the most absurd aspect of the law, which is currently still in operation, is its retroactive nature as it includes all individuals who joined the group even if their membership ended prior to the law being issued.

The Publications Law 50 of 2001 institutes a sanction of up to three years imprisonment for vague and unspecific accusations such as insulting national honor, insulting the army, violating the unity of society and disseminating false news, which provides room for a “non-neutral” judiciary to bring cases against people working in the media who criticize the state. The law also gives the Minister for Media and Communications and the Prime Minister the power to allow or prevent the issuing of publications. The Minister of Media and Communications holds the power to grant or rescind licenses for foreign and Arab newspaper journalists without any judicial or administrative restrictions. The executive authority can thus easily silence any voice.

Syrian penal law was the basis for security authorities to justify the arrest of opposition actors, relying on court decisions that condemned them. Perhaps the most important articles used were those that condemned any Syrian who sought, through action, speech, writing or other means, to split off part of Syrian territory to unite it with a foreign country, or any person in Syria who, at a time of war or anticipated war, behaved in a way that weakened national sentiment or awakened ethnic or sectarian divisions. Both these accusations were used against Kurdish Syrians or any person who sympathized with their cause.

Other articles that were frequently used as accusations against a number of opposition actors relate to undermining national consciousness, stirring up sectarian or ethnic rivalries or inciting conflict between sects or the different components of the nation, as well as membership in unlicensed parties and organizations.

We must also mention the law on combatting terrorism, which was issued as a substitute for all legislation issued under the state of emergency that was lifted after the start of the Syrian revolution. This law includes broad and very vague terms that can be interpreted according to the dictator’s whim. The law introduced a new unprecedented crime concerning the use of electronic means of communication. Article 8 of the law dictates, “Persons engaged in disseminating printed material or stored information, regardless of its form, with the aim of promoting terrorism and terrorist acts, will be sentenced to temporary hard labor, and the same punishment will be used in the case of any person who managed or used an electronic website for that aim.”

We have tried to cover above some but not all of the laws and texts used by the regime to persecute opponents, and arrest and prosecute them. It must be noted that in many cases, the Syrian regime’s security apparatus made additional accusations of immoral acts against some opponents with the aim of taking revenge against them and destroying their reputation in their social environment.

Who Kills Detainees?

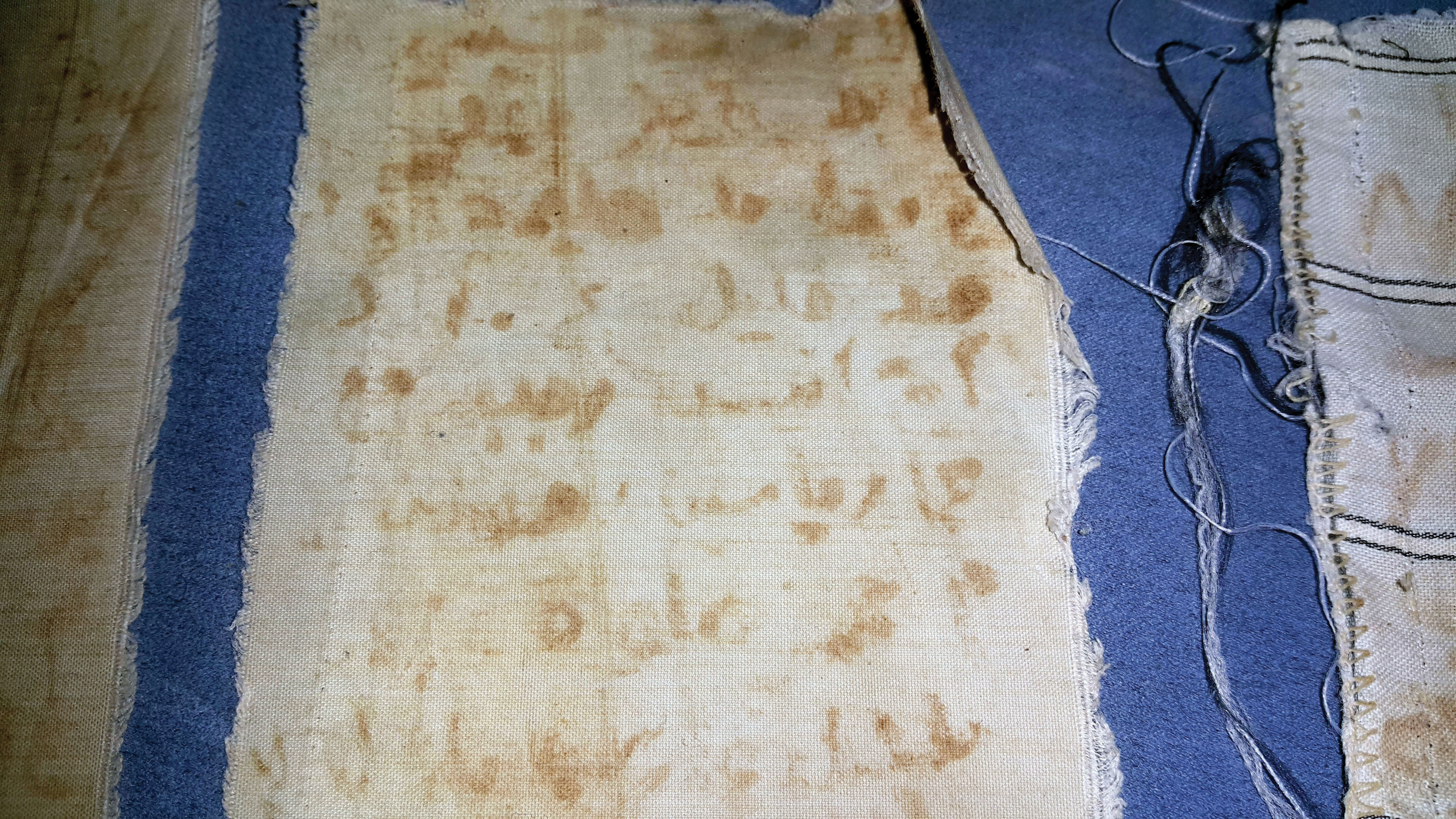

A detainee’s shirt, on which Nabil Sharbaji wrote the names of his cellmates in blood and rust, and which the journalist Mansour al-Omari took with him when he was released (Enab Baladi Exclusive, Mansour al-Omari)

Mansour al-Omari, Syrian writer and journalist

The many crimes of the al-Assad regime are known to the international community in all their different forms. Many of these crimes have been documented in their entirety and there have been attempts to prosecute the perpetrators. The regime’s crimes are perhaps the most documented throughout history, since most were observed directly by the international community, while others were documented through video recordings and the testimonies of thousands of Syrian refugees in different countries around the world. One of the most violent of these crimes is still being committed right now. As I wrote this article, a number of detainees were killed and tens of thousands more, by the lowest estimates, are struggling against death every day in regime-imposed purgatory inside the network of detention centers on Syrian territory and under it.

We all know this. But what have we done, as decent people concerned with these crimes more than those against whom we direct accusations of silence, betrayal and complicity? Do we know that every day, detainees perish and are killed in the basements of the Syrian government?

Are the detainees those we have betrayed the most? Do we know the circumstances of their detention? Who among us has not seen the picture of Cezar? Who among us does not have a detained relative or friend who was killed under torture or due to illness? Do we carry their blood on our hands?

Have we dedicated just one hour a week or a month to do something for those forgotten people under us, in the depths of the earth?

Have we managed to save one detainee from his inevitable fate? Have we established one single organization specialized in following up the cases of detainees and campaigning, using everything at our disposal, to keep the issue of detainees at the forefront of our demands? Do we search for the families of detainees to document their pain?

Who of us would dare to say that he or she has done all they could?

Have we resorted to burying the issue among al-Assad’s multiple crimes? Have our hearts gone cold? Or did we fail when our humanity was tested, even before those whom we accuse of silence, betrayal and complicity? Have we fallen lower than the international community in their record on the issue of our detainees?

Did We Kill Nabil Sharbaji?

Nabil Sharbaji, a former political prisoner killed in detention in a Syrian regime detention center in May 2015

The Syrian regime arrested Nabil on 26 February 2012 in Daraya. Nabil spent the first period of his detention in the Air Force’s investigation division in al-Mazi airport in Damascus. He was then transferred to Adra central prison and then to Sadnaya prison. Nabil struggled against fate for three years. He did not want to die. He used to sing “Raj’een ya Hawa” (We will return) in a whisper so the guards would not hear him. He wanted to return to life.

His body tried to cling to his soul in this purgatory but the feet of Sadnaya’s jailors struck his chest and sent his soul into the heavens and his body to a mass grave, or an incinerator perhaps. All we know is that we do not know where Nabil’s body is but we assume his spirit is above us, asking for forgiveness for us or perhaps cursing us.

The al-Assad regime’s monsters killed the journalist Nabil Sharbaji in May 2015, sending his soul to join the many others watching us from above.

Nabil spoke to us many times but we did not really listen to him. He documented the names of his cellmates from inside his silent cement cell but we did not appreciate the risk he took or say thank you.

From his cell, Nabil wrote using his finger and blood from a bleeding cellmate’s gums mixed with rust, the names, telephone numbers and place of residence of all his cellmates on a piece of cloth for it to be smuggled out of prison. The cloth, which was part of a shirt belonging to another inmate, was smuggled out by journalist Mansour al-Omari when he was released.

Nabil communicated with us what was happening in the basement of al-Assad’s prisons in a letter smuggled out of Adra prison. In it he wrote:

“Mansour, my friend, I was so sad when you left us. I tried to continue what you started and I did continue but the conditions have changed a lot and it has become too difficult… We are now 90 people in one room… I miss singing together and you telling us about films. You amazed me you and ****** all the time you were here… By Allah we will return, my friend, to the tune of Raj’een ya Hawa… Peace. Adra Central Prison. 15/04/2013.”

Nabil had hopes of surviving more than once and we let him down each time.

Omar al-Shaghiri, one of the people who witnessed Nabil’s death in detention, said, “The jailor used to come every morning and shout, “Bastards, who has someone who died?” That day, the cell officer in the cell next to mine said he had someone. The jailor asked him for the full name, mother’s name and date of birth. The officer responded, ‘Nabil Sharbaji’. Then he said his father’s name, mother’s name and his date of birth. I remember that day well. One of Nabil’s closest friends was in the same cell as me and he cried when he heard Nabil’s name. His mental state and health deteriorated after hearing of the death of one of his dearest friends.”

if you think the article contain wrong information or you have additional details Send Correction

النسخة العربية من المقال

-

Follow us :

Scene from Tadmur (Palmyra) produced by Umam Foundation for Research and Documentation (Film Official Website)

Scene from Tadmur (Palmyra) produced by Umam Foundation for Research and Documentation (Film Official Website)

A

A

A

A

A

A

More In-Depth

More In-Depth