Odada Kojan – Enab Baladi

Syria’s borders have not remained stable since the start of the twentieth century. Since the fall of the Ottoman Empire and the beginning of the British and French mandate period, Greater Syria lost half its regions and provinces. These changes raise serious questions regarding Syria’s future and its current borders – will it maintain them or will it contract again in light of the war underway since April 2011?

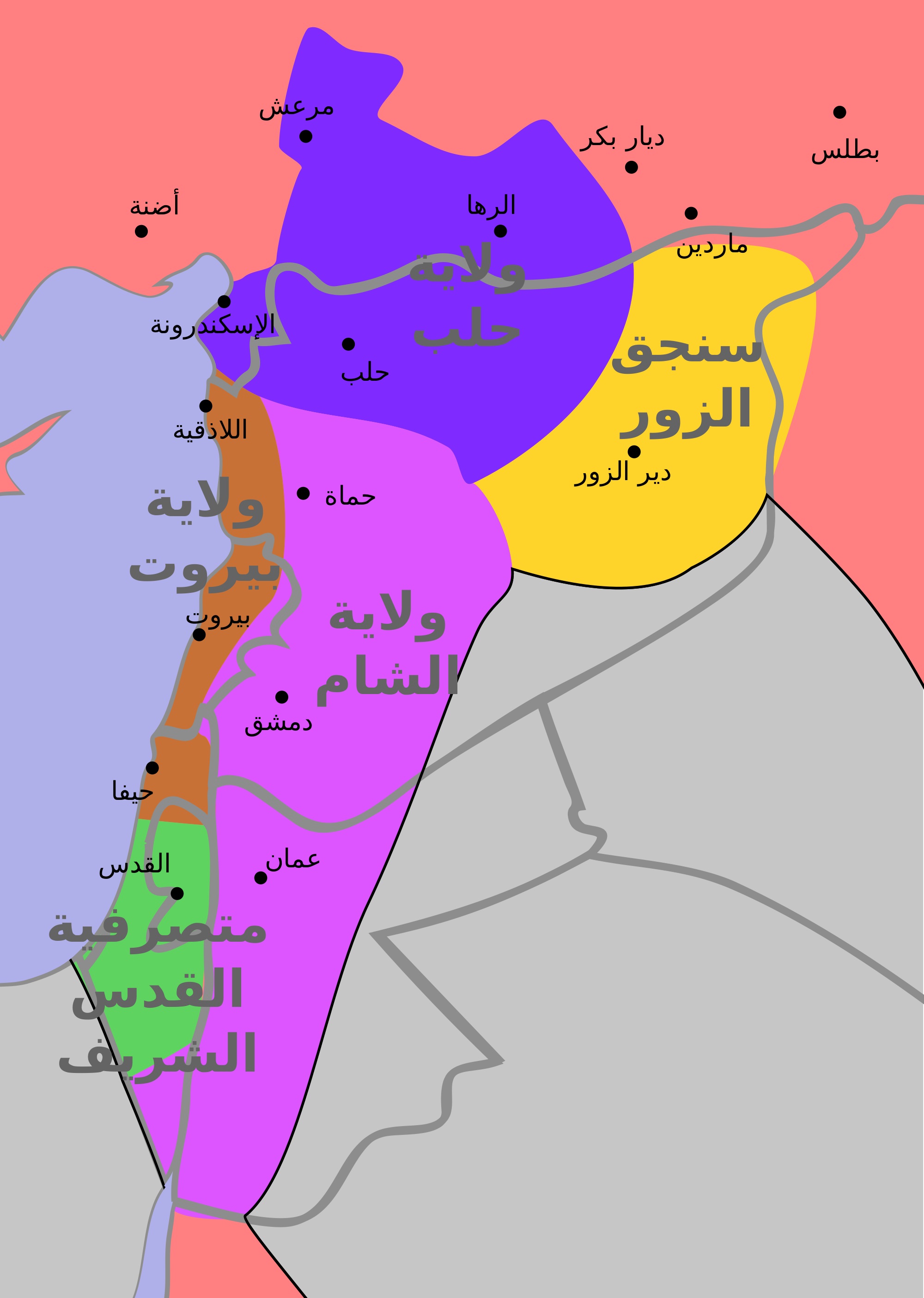

Greater or “Natural” Syria

Greater Syria or “Natural Syria” as it is called in Arabic, is a geopolitical term to describe countries that currently form the Levant (Bilad al-Sham) – Syria, Jordan, Palestine and Lebanon – including areas that are currently under Israeli control. It also includes areas in southern Turkey such as Adana, Mersin, Gaziantep, Kahramanmaraş, Alexandretta, Diyarbakir, Urfa and Mardin. These areas were part of one entity until France and Britain announced their mandates in the region in 1920.

In a series of British-French written exchanges that led to the Sykes-Picot agreement, Aristide Briand, the French Prime Minister, recommended on 9 October 1915, “Maintaining the current administrative borders of Syria and its lands including the provinces and Ottoman administrative regions of Jerusalem, Beirut, Lebanon, Damascus and Aleppo, and in the North West all of Adana province south of the Taurus mountains.”

Following Briand’s recommendations, Syria lost Jerusalem, Beirut, Adana and many other areas. Enab Baladi explores these losses, summarizing the geographical and on-the-ground conditions in Syria to predict the country’s future in light of a complicated national and international conflict.

The Agreements That Tore Greater Syria Apart

Between 1916 and 1939, several agreements were made on the ruins of the disappearing Ottoman Empire, dividing Greater Syria into four countries subject to French and British mandates, some of which (in the northern regions) was later taken over by Ataturk’s Turkey.

Sykes-Picot Agreement, 1916

As the First World War raged between Germany and the Allied powers, London and Paris (the decision-making capitals at the time) mandated Sir Mark Sykes as Britain’s representative and Mr. George Picot as France’s representative, as they were seen as the shrewdest and most capable diplomats at the time.

The Sykes-Picot agreement dictated the division of the Levant and Mesopotamia into three areas: Iraq under British administration, Syria under French sovereignty and Palestine under international administration as a prelude to its occupation by the Jews later in accordance with the Balfour Declaration.

The Syrian lands under French control extended from the eastern coast of the Mediterranean to the city of Mosul, which was part of Syria according to the agreement. It also included provinces now within southern Turkey including Alexandretta. The Iraqi lands under British control extended to the western and southern shores of the Arab Gulf including Kuwait and extending to Jordan.

The decision-making states took advantage of the sickness afflicting the Ottoman Sultanate and executed their agreement, which drew borders between Arab states. These borders are highly unstable today in light of the conflict in the Middle East, a conflict that may produce new borders that will further deepen divisions.

Treaty of Sevres, 1920

On 10 August 1920 in the French area of Sevres, a treaty was signed between the Ottomans and the victorious Allies of the First World War. The treaty was the final nail in the coffin of the Ottoman Empire as its terms included the Ottoman government relinquishing all areas whose inhabitants spoke languages other than Turkish, including Arab areas. Syria, Iraq, Egypt and Hijaz were no longer officially part of the Ottoman state, leading to the formation of new borders and multiple states in the region.

Ankara Agreement, 1921

After the Sevres Treaty, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk led the “war of independence” to restore Turkey’s pride, overthrow the Ottoman government in Istanbul and regain the lands mandated by Britain, France, Greece and Italy. The Ankara Agreement was signed between France and Turkey on 29 October 1921 in the Turkish state’s new modern capital, Ankara. The agreement redrew Syria’s border with Turkey, giving Turkey the northern regions of Syria including Adana, al-Othmaniya, Kahramanmaraş, Gaziantep, Kilis, Urfa, Mardin, Diyarbakir, Nusaybin and Cizre.

Lausanne Conference, 1922-1923

This conference, hosted in the Swiss city of Lausanne, did not directly affect Syria’s borders after France had changed it to Turkey’s advantage in 1920, but gave Turkey international recognition for its current borders including the regions taken from Syria.

The conference, which came just 20 days after announcement of the dissolution of the Ottoman Sultanate, failed to impose British conditions that the new state announce that it was secular, agree to freedom of water navigation in the straits, expel the Ottoman Sultan and his family and relinquish control of the oil-rich Mosul region.

The second conference held in Lausanne in November 1923 saw greater flexibility from Ankara and its willingness to sign the agreement relinquishing Syria, Iraq, Egypt, Sudan and its privileges in Libya. The agreement gave Turkey its current land and nautical borders with the exception of Alexandretta, which was later included as part of Turkey.

Stripping of Alexandretta Province, 1939

Alexandretta province is situated North West of Syria along the Mediterranean Sea. The province is 4800 kilometers squared and was part of Aleppo province during the Ottoman period. It currently includes a number of cities and towns, the most important of which are Antioch, Alexandretta, al-Reyhanli and Kharakhan.

Alexandretta was one of the most prominent problematic issues between Syria and Turkey between the years 1916 and 1939. Following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, the area was granted autonomous rule under Syrian authority but was subsequently integrated within the Syrian state in 1926 under Syrian president Ahmad Nami.

France obtained a League of Nations decision in 1937 granting Alexandretta autonomous rule and nominally tying it to the Syrian government in Damascus. However, France withdrew from the province when Turkish forces entered in 1938.

In 1939, Turkey held a referendum in the province, overseen by France, which revealed popular support for the province’s official inclusion within Turkey. The province was thus integrated into Turkey despite Arab discontent and doubts concerning the referendum results. Today the province is included within Turkish territory under the name “Hatay province”.

The stripping of Alexandretta was a shock to Syrians and angry protestors took to the streets of Damascus, Aleppo and other Syrian provinces to oppose the move. The demonstrators overthrew the government of Jamil Mardem, causing the resignation of the president Hashim al-Attasi. Alexandretta province continued to be a source of direct conflict between Syria and Turkey for decades.

The Six Day War, and the Occupation of the Golan Heights 1967

The Golan Heights are situated south west of Syria and to the west of the capital Damascus. The area, which measures around 1800 kilometers squared, was administratively part of al-Quneitra province before most of it was occupied by Israel in June 1967 after it defeated Syrian and Egyptian forces in what is commonly referred to as the “June Naksa” (Naksa meaning catastrophe in Arabic).

The Syrian army tried to regain the Golan in the October 1973 war but failed. The Israeli forces withdrew approximately 60 kilometers leaving the destroyed city of al-Quneitra and its outskirts. Tel Aviv effectively maintains two-thirds of the Heights and the Israeli Knesset unilaterally decided to incorporate the area into the Israeli state in 1981.

Thousands of families migrated from the Golan to Syria’s interior while around 40,000 citizens preferred to remain in their homes. Syria’s demands for the return of the Golan after the 1973 war became a mere show as no measures were taken to effectively regain the occupied land. Opposition activists allege that Hafez al-Assad relinquished this water-rich and fertile area in secret agreements with Tel Aviv.

The Revolution and the Reality of Frayed Borders

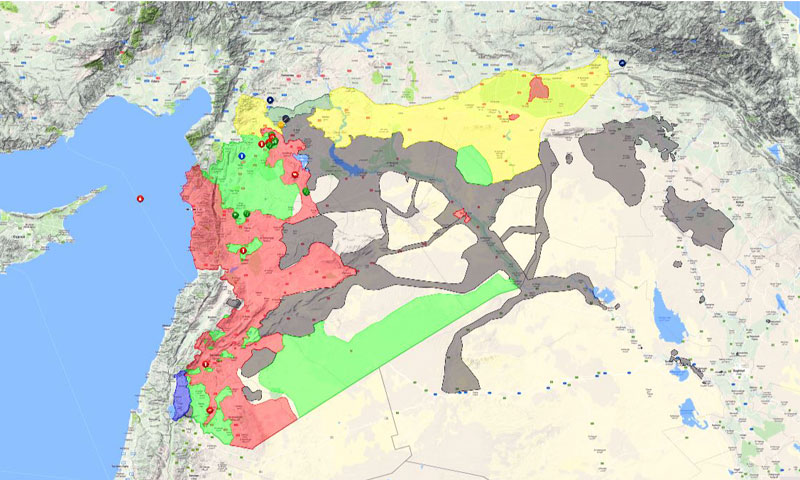

Geographical map showing the distribution of military forces controlling Syria, 6 November 2016 (livemap)

Syria maintained stable administrative borders during the four decades that preceded the revolution against Bashar al-Assad. Turkish-Syrian relations gradually improved especially at the end of Hafez al-Assad’s reign. The two sides signed the Adana Security Agreement in 1998, which strengthened trade and political relations between the governments of Recep Tayyip Erdogan and Bashar al-Assad from the early 2000s until April 2011.

This occurred at the same time as conflict with the Israeli “enemy” subsided on all fronts. Land borders with Jordan and Iraq also remained stable, not undergoing any changes after demarcation by London and Paris despite the cessation of diplomatic ties and the rivalry between Hafez al-Assad and Saddam Hussein.

In the third year of the revolution against the Syrian regime, Syria’s administrative borders began to weaken and fragment. This is fundamentally due to the al-Assad government losing control over most of its border crossings as well as migratory movements as Syrians escape the war and seek refuge in neighboring states, new militias and armed organizations joining the conflict and direct international intervention in Syria, which threatens to bring about geographical changes in Syria in the near future.

Syria’s current borders

Syria’s current territory measures 185,000 kilometers squared and its border with its neighbors is around 2250 kilometers long. To the east, it shares a 605 kilometer-long border with Iraq; to the south west, a 76 kilometer-long border with the Palestinian state; to the south, a 375 kilometer-long border with the Jordanian Kingdom; and to the west, a 370 kilometer-long border with the Republic of Lebanon. To the north, it shares an 822 kilometer-long border with the Turkish Republic.

Turkey Oversees Euphrates Shield Operation from the Inside

Turkey directly oversees the Euphrates Shield operation rooms since August 2016. The Free Syrian Army factions supported by Ankara managed to take control of vast areas of Jarablus city and even Azaz city north of Aleppo in a strategy that includes the cities of al-Bab and Manbaj, according to Turkish statements, to form the “safe zone” that Turkey has repeatedly been proposing for the past year.

The Syrian-Turkish border in the provinces of Aleppo and Idlib is under Turkish control except for the areas of Kobani and Afrin. Turkish forces contributed to expelling “Islamic State” forces from these areas, strengthening Turkish influence in northern Syria.

The Turkish president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, said on 22 October 2016, “Some actors are asking Turkey not to take control of the town of al-Bab but the Syrian opposition forces supported by Turkey are determined to take control of the town to establish a terrorist-free zone there.” He added, “We respect the existing international political borders, despite the anguish in our hearts… We have no problem with the sovereignty of any neighboring state. Our primary concern is protecting our brothers and our heritage.”

Vast “Autonomous Administration” Borders Turkey and Iraqi Kurdistan

The “Autonomous Administration” announced by the Kurdish Democratic Union Party controls most of the border regions with Turkey in al-Hasakah, al-Raqqah and Aleppo provinces. Turkey accuses the Kurdish armed groups in Syria of being under the directly control of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) and of military cooperation with the PKK.

Ankara announced in the beginning of November that a tunnel extending from Nusaybin in Turkey to al-Qamishli in Syria was blown up, which indicates military cooperation between the two Kurdish areas. Despite this cooperation, Turkey effectively controls the border region and regulates border movement.

The “Autonomous Administration” controls the border regions with Iraq to the east of al-Hasakah province, where the areas on the Iraqi side are under the control of the Kurdish Regional Government. This part of the border witnesses extensive trade activities including the transportation of individuals and trucks via the Simalka border crossing point.

“Islamic State” Connects Syria to Iraq

The “Islamic State” obliterated the border between Syria and Iraq in Deir Ez Zor province and in the southeastern parts of al-Hasakah province. This area between the two countries has become a single entity without administrative borders since the start of 2014.

The effacing of these borders has facilitated the movement of “Islamic State” fighters, Arab and foreign, between the two countries. There is significant economic exchange between the areas, especially trade in fuel derivatives, which provide foreign currency for the “Islamic State” treasury. The group’s control over this area provided the United States and allied countries an excuse to launch ground and aerial attacks in Syria, set up military bases in al-Rmelan in al-Hasakah province and arm local factions to fight “Islamic State” forces.

Israel Moves on the Southern Border

The southeastern border with the land occupied by Israel has witnessed tensions and intermittent shelling by the Israeli army as a response to the rockets that sometimes fall on Israeli settlements in the occupied Golan Heights. Human rights organizations have documented Israeli hospitals admitting tens of wounded Syrians in light of the absence of the Syrian regime’s authority in most of the areas bordering the entity with the exception of the district of Hadar, which is subordinate to al-Quneitra.

In July 2016, Israeli forces crossed the border with Syria and several armored vehicles entered 400 meters into Syria close to Tel Okasha in al-Quneitra province. According to the local council of opposition groups, the Israeli army established a military post in an unprecedented move and placed barbed wire around the area it entered, which was previously under the supervision of the United Nations Disengagement Observer Force.

Observers see Israel as clearly taking advantage of the situation and war in Syria to reinforce Israeli military control in the occupied Golan Heights. Observers suggest Israel will resort to similar steps in the future causing Syria to lose more land.

Jordan: Unilateral Border Control

With Jordan closing its border crossings with Syria and limiting border movement to humanitarian convoys and evacuation of the injured, Jordan has gained sole control over the border without the Syrian regime having an active presence on the other side, despite the regime holding the border in al-Sweida province.

Jordan uses its border with Syria to support the southern front of the Free Syrian Army through a support coordination room (MOC). It has also contributed by establishing training centers for the “New Syrian Army” in rural areas in the border region with Syria in coordination with the United States and Britain.

Syria’s Border With Lebanon Under Hezbollah Control

Along the western border with Lebanon, the official Lebanese-Syrian border has become a mere formality due to the domination of Hezbollah’s militia of the areas extending from Homs’ western rural areas until the area south of al-Qalamoun in Damascus’s rural outskirts.

Hezbollah has disregarded the borders, effectively controlling several cities and towns in the two provinces including the border city of al-Qasir and its rural outskirts, the city of Yabroud in al-Qalamoun and the villages surrounding it such as Falitet and Asal al-Ward.

By controlling the border, with the Syrian regime’s consent, Hezbollah ensures that its fighters can cross into and out of Syria. Hezbollah is the most prominent foreign auxiliary force supporting the al-Assad forces. The militia has strengthened its position through its local control in light of the retreat of opposition factions from the area.

Forecasting The Next Stage: Will Syria Remain or Disappear?

Will Syria remain or disappear? Will it witness division or federalization? Will it maintain its administrative borders or will they shrink once more? Enab Baladi put these questions to political scientist Sasha al-Alo in an interview in which the researcher explained that all these questions will be answered by the shape of the future political system in Syria.

Division and Federalism

Federalism, if it is implemented in Syria, will take place in an unnatural context. Federalism usually follows a phase of administrative centralization followed by political centralization, based on a free market and an economic system that aligns with federalism. In the current situation, the region is moving according to the Americans’ “creative chaos” theory, according to al-Alo.

Al-Alo explained that the “creative chaos” theory dictates that local forces fight in the area and that the winner and survivor will be “cleaned up” and prepared for the task of governing. Thus, it is the legitimization of chaos. “If we are unable to control this chaos and the conflict spreads, then the north with its factions will gain recognition, as will the south, the areas under regime control and the Autonomous Administration. This will mean a federation without any clear political, administrative or economic system.”

Al-Alo sees that the ongoing battle for Mosul against “Islamic State” forces has special significance for Syria, since the “Islamic State”, once expelled from Iraq, will withdraw into Syria and all its fighters will cross into Syrian territory.

Despite this, al-Alo sees neither hypothesis – division or federalism – as likely. He explained that the options currently available to Syria are shaped by international and regional interests and no side has an interest in seeing Syria divided. Although this is a policy that Israel has always pushed for, in the Syrian case it would not be in their interest as the Americans have warned Tel Aviv that federalism or dividing up states in the region such as Iraq, Syria, Jordan and Lebanon would lead to US support for the two-state solution in Israel, which is something Tel Aviv does not want.

Neither of these options is in the interests of the Iranians, as Tehran wants Syria to remain whole so it can retain its ports on the Mediterranean Sea, according to al-Alo. Iran’s position is shared by Turkey, which is seeking to curb Kurdish ambitions. Dividing up Syria would lead to the emergence of new ethnic-based nation states, from which Ankara would be the biggest loser. This is why both the Iranians and the Turks oppose the Israeli project for dividing the region.

The choice of federalism would weaken the Syrian regime (the central government) and place it in a difficult position. Analysts suggests that al-Assad may retreat to the coast and accept an Alawite state if the country is divided. However, he adamantly rejects the two options because they would erode the basis of his legitimacy as president vis-à-vis his sect and supporters.

According to Al-Alo, “Syria’s geography, as much as it is a curse for Syria, is also its source of protection. The changes we are seeing are a result of its position next to Israel and Turkey at the centre of equilibrium and politics in the region.” He clarified that the role Syria played under Hafez al-Assad is now being played by Turkey after it became the balancing power in the region due to the intersecting interests it shares with international actors.

Fragile Borders Open The Door for Many Possibilities

Regarding Syria’s borders, al-Alo indicated that no one completely controls them today, but it is possible to reassert points of control, as Israel has done. Taking advantage of the situation in the past five years, Israel has sought to obtain international recognition of the current border and to legally include the Golan Heights within its territory, in an effort to redraw the borders drawn before 1967.

According to Al-Alo, the Turks are known to have intervened in Syria to protect Turkish national security. He said, “The Turks, in their way of thinking and the nature of the current ruling party, have a very mercantile mentality and they approach areas as investments. For example, all Syrian organizations are prevented from entering Jarablus as all the organizations operating there are exclusively Turkish.”

There is no doubt that the future of Syria is uncertain. It is difficult to predict the future governance system and the shape of the country after the war, but the current variables are complicated and the regional interventions are unprecedented, threatening to fracture Syrian unity once more. Perhaps we will witness agreements like those that occurred in the twentieth century, which would break Syria into states or regions defined by religion or ethnicity in the absence of inclusive national unity.

Al-Alo rejected the idea that Turkey entered northern Syria with the aim of taking control of new areas. Rather, it is an alliance aimed at filling the vacuum following American withdrawal from the region and Russia and Iran taking its place. He said, “Turkey’s role here is to act on two fronts. Turkish-Russian relations have improved remarkably while Turkish-Iranian relations do not appear to be negligible. So it is possible to disagree in Mosul and coordinate in Syria.”

At the same time, he indicated that Syria’s borders are now malleable after they were broken by the “Islamic State” which has made it impossible to isolate Syria from changes in the region. For example, Sunni Muslims in Syria face a situation of extreme persecution just like the Sunnis of Iraq. Al-Alo said, “If you grant federal self-rule to the Sunnis of Syria in the event of a particular geographical border, it is possible that in the long term they will join up with the Iraqis. It is a project many established figures in both countries have called for.”

Al-Alo reiterated that the future political system in Syria will determine the country’s sovereign identity and administrative borders. He said, “We are before multiple choices among them resorting to a quota system based on sectarian quotas like Lebanon and Iraq. Looking at the experience of those neighboring states, this system presents a danger to the borders as the decisions of the Druze of Syria will be made by the Druze of Lebanon, and the decisions of the Kurds of the Autonomous Administration will come from Erbil or Kandil based on political mobilization, not because they are subordinate but because those models have been in place for longer.”

The “fight against terrorism” is weakening and destroying borders. As long as organizations classified as “terrorist” are present in Syria they will provide an excuse for all sides to cross the border or violate the borders at any time. “Terrorism” gives political legitimacy to any side seeking to intervene in Syria using the excuse that they are fighting it, according to al-Alo.

A No-Fly Zone And Its Disadvantages

Regarding a secure no-fly zone and Turkey’s major role in achieving it, al-Alo explained that the decision to establish it has already become a reality even if it was not officially issued. He indicated that according to information he received, the FAO organization under the United Nations has held meetings with organizations with the aim of planting vast tracts of land in the areas now under the control of the Euphrates Shield forces in northern Syria. He added, “Considering that the FAO has entered this area, the decision to set up a no-fly zone has been implemented.”

The political scientist indicated that the population in the northern area is a mix of Arabs, Kurds and Turkmen. Gathering them in the no-fly zone in order to later cut the area out and incorporate it into Turkey is highly unlikely as the population is heterogeneous. He said, “I cannot guess if Turkey will take it or not, but I can confirm that this area is harmful to Turkey as it would lead to a decrease in Turkey’s role in Syria on the basis that it has guaranteed its security by setting up a human shield, then a military shield then a border. It is also possible that this would legitimize the regime targeting other areas as any area outside the regime’s control would not be safe, according to local perception.”

Al-Alo pointed out that the Turkish mentality is purely financial and that they aim to invest their influence and not to control the land, “They may drown Aleppo with their products in the future. It is also possible that they may keep some oil wells under the control of the Turkmen, which would guarantee their political power in Syria in the future. They do not have a developed ideological project in the area, unlike the Iranians who support the regime and want to control the land… The Turks’ project does not go beyond the economy, as it is the motor for their progress.

if you think the article contain wrong information or you have additional details Send Correction

النسخة العربية من المقال

-

Follow us :

Most viewed

- Printing Syrian currency in Europe... A file on the table

- Black market traders manipulate dollar prices under eyes of Central Bank officials

- AANES insists on decentralization in Syria

- Al-Sharaa attends 4th Antalya Diplomacy Forum

- Books make a comeback in Damascus libraries after being banned under Assad

A

A

A

A

A

A

More In-Depth

More In-Depth