Enab Baladi – Khaled al-Jeratli

The draft constitutional declaration received a wave of criticism after it was handed to the Syrian transitional president Ahmed al-Sharaa on March 13. This was followed by attempts to clarify some of its provisions, while the debate focused on articles that observers believe pave the way for absolute powers in the hands of the president.

The declaration sparked widespread controversy, especially in northeastern Syria, as both the Syrian Democratic Council (SDC) and the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES) as well as their traditional rival, the Kurdish National Council (KNC), argued that the proposed constitution did not acknowledge the rights of Syrian components, including the Kurdish component.

On the other hand, Syrian legal experts pointed out the provisions related to presidential powers, noting that the draft did not clearly define the powers of the president, or the mechanisms for holding him accountable if he errs, or even the accountability of ministers, along with the part that talks about appointing one-third of the members of the Syrian parliament by the president.

The ongoing debate on the draft declaration also touched on the identity of the state, which the committee left as stated in the previous constitution: an Arab Republic governed by a Muslim president, whose laws are derived from Islamic Sharia.

The president appoints those who hold him accountable

Just hours after announcing the draft constitutional declaration, the spokesperson for the drafting committee, Abdul Hamid al-Awak, stated at a press conference that the committee chose a political system that relies on a complete separation of powers.

Al-Awak added that the proposed political system in the draft constitutional declaration helps manage the transitional phase, noting that the parliament has no authority to hold the president accountable, nor does the president have the authority to dismiss or hold parliament members accountable.

For her part, committee member Riaan Kahilaan said during the same press conference that under the presidential system based on strict separation of powers, the president is not accountable before the parliament, but rather the president will form a high constitutional committee comprised of qualified individuals, which will be responsible for holding the president accountable.

She pointed out that according to the characteristics of the presidential system, this committee is not concerned with the work of the parliament, and the parliament is not concerned with its work.

Syrian lawyer Ghazwan Kurunful said that the heavy concentration of power in the hands of the president, who assumes the executive management of the country without being accountable for his actions and without the possibility of being questioned or held responsible as the head of the executive authority, constitutes a valid criticism.

He added that the justification provided by committee members, stating that they adopted a presidential system that does not allow for holding the president accountable, is inaccurate, asserting that these justifications contradict the realities and constitutional facts of the world.

The committee that prepared the draft constitutional declaration claimed that this system is adopted in many presidential systems, including the United States, but Kurunful said that this comparison does not reflect reality, as in the United States, the president is accountable for his administration’s actions and can be questioned by the Congress if he errs.

Kurunful continued that the Congress has in certain cases the ability to impeach the president, like when they initiated proceedings against President Nixon over the Watergate scandal, which forced Nixon to expedite his resignation to avoid impeachment, and the case of Clinton when he lied under oath to cover up his affair with Monica Lewinsky, which compelled him to admit he lied and later apologize to the nation.

The Syrian lawyer pointed out that in the Syrian case, the president is not only immune from accountability and impeachment, but he also appoints members of the constitutional court, and he appoints members of the parliament, which does not have the authority to summon the president in his capacity as head of the executive authority to hold him accountable for issues related to actions or decisions issued by his administration, nor does it have the authority to question ministers.

He added, “With this declaration, we are creating a Pharaoh,” as he put it.

Enab Baladi attempted repeatedly to contact members of the draft constitution preparation committee and its spokesperson to clarify the points that received criticism, but did not receive a response to the questions up to the time of writing this report.

The draft sets the transitional period at five years and grants the president the right to declare a state of emergency.

The declaration emphasizes the importance of judges and their rulings and their independence and leaves the matter of dismissing the president or limiting his powers to the parliament.

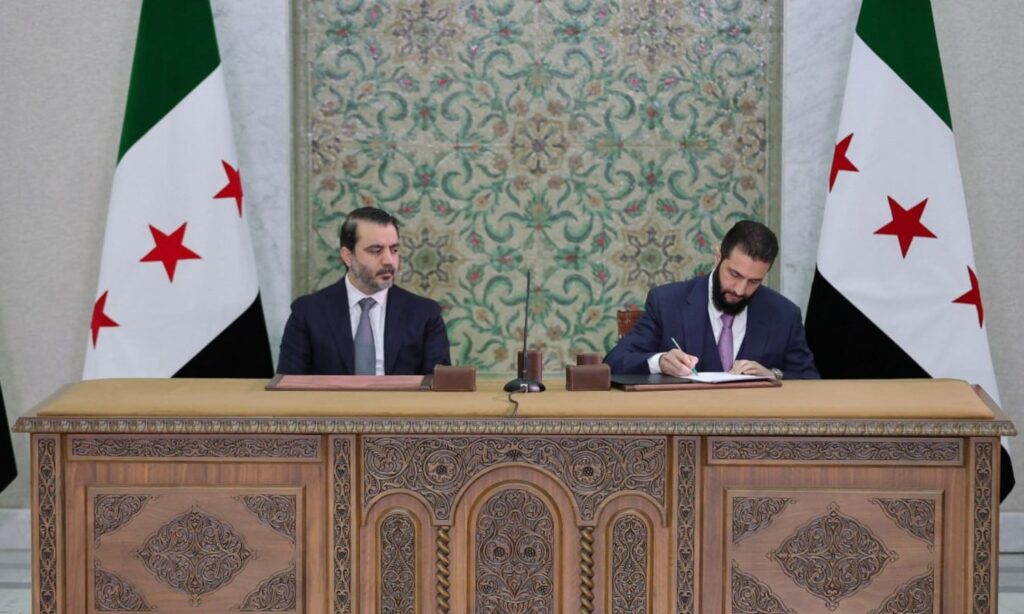

Al-Sharaa issued a decision to form a special committee to draft the constitutional declaration in Syria on March 2.

The committee includes Abdul Hamid al-Awak, Yasser al-Huwaish, Ismail al-Khalfan, Riaan Kahilaan, Muhammad Ridha Jalakhi, Ahmad Qurabi, and Bahia Mardini.

The identity of the state and the president

Article one of the constitutional declaration mentions the name of the Syrian Arab Republic as defining the identity of the state, while article three reiterates what was stated in previous constitutions, stating that the religion of the president of the republic is Islam, and Islamic jurisprudence is the main source of legislation. Article four stipulates that Arabic is the official language of the country.

Article ten also states that Syrian citizens are equal before the law in rights and duties, without discrimination based on race, religion, gender, or lineage.

Article 15 of the declaration mentions that work is a right for citizens, and the state guarantees the principle of equal opportunities among citizens.

The Syrian lawyer Ghazwan Kurunful noted during his conversation with Enab Baladi the existence of a contradiction between the provisions, as it is impossible to consider citizens equal before the Syrian law in rights and duties while requiring that the president of the republic be a Muslim.

Kurunful stated that “the religion of the head of state contradicts the principles of equal citizenship and equal opportunity in holding public office and undermines them.”

He added that the constitution is not only rigid rights texts but must also be a space for national convergence and a comprehensive scope for all Syrians, not a hub of estrangement, disagreement, and national division, as he expressed.

Criticism in two directions

The criticisms directed at the constitutional declaration displayed several apparent patterns, including mixing the nature of the constitutional declaration with that of permanent constitutions, calling for more constitutional articles and numerous details. Another focus was on key issues related to identity, such as the name of the state, the religion of the president, and the relationship between religion and the state, as stated by the legal researcher at the Syrian Dialogue Center, Nawras al-Abdullah, to Enab Baladi.

Al-Abdullah considered that the committee that worked on preparing the draft constitutional declaration logically focused on previous agreements in Syria, especially the constitution of 1950, which it granted a special place, and added texts guaranteeing diversity and showing cultural and linguistic guarantees for Syrians, as in Article seven of the first chapter.

Article seven emphasized the establishment of coexistence and societal stability, preservation of civil peace, prevention of forms of sedition, and also assured the cultural diversity of society with all its components, alongside the cultural and linguistic rights of all Syrians.

A section of the criticism addressed changing the form of governance to a presidential system in Syria, which is a critical issue that varies in opinions between those fearing the emergence of a new dictatorship and those viewing it as a practical and realistic necessity, presenting numerous international examples of the success of this system in democratic countries like the United States, according to the researcher.

Al-Abdullah considered it necessary to observe two aspects within these criticisms. The first is natural within the presidential system, namely the concentration of executive powers in the hands of the president due to the absence of a prime minister. The second is the lack of a clear provision for the president of the republic to preside over the Supreme Judicial Council, which is a positive aspect for the independence of the judiciary.

He pointed out that the persistent text allowing the president to appoint members of the constitutional court represents a stalemate, and it could also have advanced toward independence, such that the members could be elected by the parliament, alongside the absence of any text granting the president legislative powers as was common in previous constitutions, where his role was limited to presenting laws, which is a normal matter.

Kurdish rejection

Following the signing of the draft constitutional declaration, various Syrian parties issued positions regarding it. The Syrian Democratic Council (SDC) announced its rejection of the constitutional declaration, stating that its stance is an extension of its rejection of the National Dialogue Conference, asserting that everything built on the outcomes of this conference “will remain inadequate to address the national issue.”

The SDC, which is the political umbrella for the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) in eastern Syria, stated in a press release that the constitutional declaration “reproduces tyranny in a new form, consolidates central governance, and grants the executive authority absolute powers, while restricting political activity and freezing the formation of parties, which disrupts the path toward democratic transformation.”

The Kurdish National Council (KNC), one of the pillars of Kurdish politics in northeastern Syria, also expressed its rejection of the constitutional declaration.

Shelal Kado, a member of the General Secretariat of the Council, told the Rudaw news network that the constitutional declaration “was written with a mentality based on one nation and one religion,” and it does not guarantee the rights of the country’s various national and religious components.

Kado called for certain measures to amend the declaration so that it “guarantees the rights of all nationalities and components in the country, because five years is not a short period for managing a country.”

For its part, the Autonomous Administration pointed out that the new document “contains clauses and a traditional style similar to the standards and measures applied by the Baath government.”

It added that the declaration contradicts the reality of Syria and the existing diversity within it, describing it as “a true distortion of Syria’s national and social identity.”