Muhammed Fansa | Yamen Moghrabi

The Syrian humanitarian crisis has become a political one that has extended to neighboring countries, as regional countries agreed to call for the return of Syrian refugees under the pretext that they have become a heavy “burden,” while international actors tend to mass financial capabilities to repel the Russian invasion and to use what is left to solve the refugee crisis.

The length of the Syrian crisis, with the lack of prospects for a political solution in Syria, has contributed to the yearly decline in humanitarian support, in parallel with the increasing need for aid, especially after the Feb.6 earthquake, in Lebanon and Jordan recently.

In this file, Enab Baladi explores the reasons for the decline in humanitarian aid to the Syrians and its impact on the displaced and refugees. It also tries to explain with experts and analysts how host countries, donors, and the Syrian regime have dealt with this crisis, the backgrounds of Jordan and Lebanon’s policies, and their engagement in discussions with the regime in Syria regarding the return of refugees.

More than 4 million Syrians affected

An unprecedented wave of aid cuts has affected more than three million displaced Syrians and refugees at a time of dire need, and international organizations are setting records in poverty levels this year, in addition to the closure of the main crossing for aid entry into northern Syria.

On June 13, the World Food Programme stated that the “fast-depleting funds are forcing the WFP to cut food and cash-for-food assistance for nearly half of the 5.5 million people it supports in Syria, from July.

“The move is a last resort that will harshly impact up to 2.5 million people dependent on what are already half-rations on which they can barely survive,” the WFP stated.

In Syria, WFP urgently requires a minimum of $180 million to avert cuts and continue providing food assistance at its current level until the end of the year.

“Instead of scaling up or even keeping pace with increasing needs, we’re facing the bleak scenario of taking assistance away from people right when they need it the most,” says WFP Representative and Country Director in Syria, Kenn Crossley.

The WFP counted on the pledges of the seventh Brussels Conference on “Supporting the Future of Syria and the Region,” which aims to mobilize funds for Syrians in need of aid and for neighboring countries hosting refugees.

The International donors on June 15 pledged 5.6 billion euros ($6.13 billion) at an EU-hosted conference in Brussels. The pledges include 4.6 billion euros for 2023 and one billion for 2024 and beyond to support people inside Syria and neighboring countries hosting Syrian refugees, according to Reuters.

In addition, international financial institutions and donors have announced 4 billion euros in loans, bringing the total of grants and loans to 9.6 billion euros.

As of the end of July, 77% of the UN response plan for the current year from donor countries and institutions is still not funded, according to UN data, and only 27.4% is funded by the UN response plan to the earthquake in Syria and Turkey.

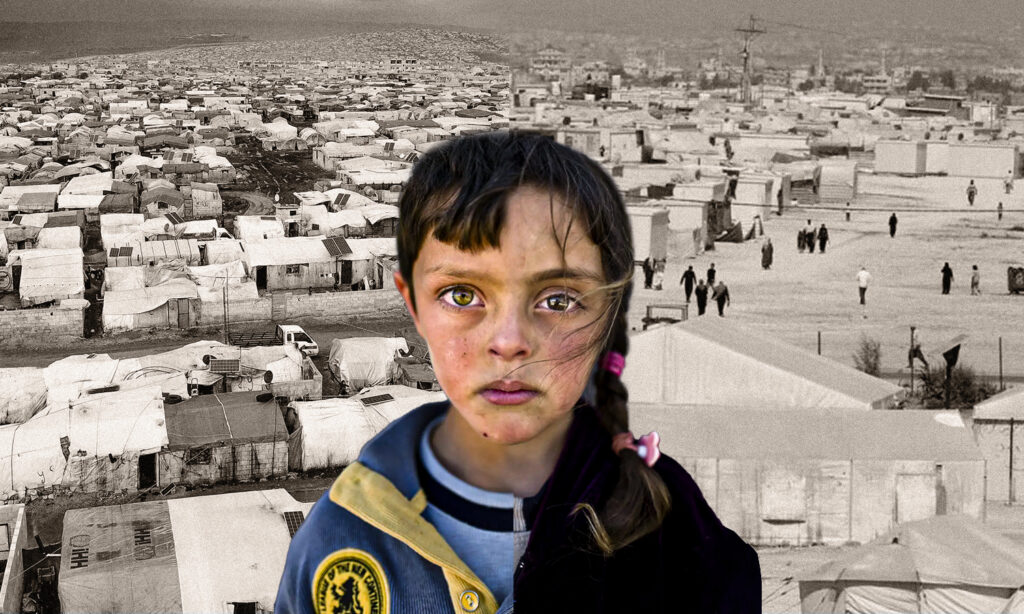

Syrian children stand in a refugee camp in the town of Bar Elias in Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley – July 13, 2023 (AP)

In Lebanon, the Syrian refugees were affected by the sharp decline in the value of the Lebanese pound against the dollar, which led to a decrease in the value of aid, prompting the United Nations to demand cash assistance in dollars for the refugees, which was rejected by the Lebanese caretaker government, according to what the United Nations reported in a statement last May.

Syrian refugees used to receive UN aid in Lebanon in Lebanese pounds until the UN demanded the “dollarization” of aid (the delivery of money in dollars) to the refugees due to the difficulty of securing large amounts of Lebanese cash in bank machines, due to the sharp drop in the value of the local currency.

The Lebanese government justified its refusal of the UN’s request to “dollarize” the aid, saying that this step would “exacerbate the crisis” between the Syrians and the Lebanese so that about 230 thousand Syrian families would receive two and a half million Lebanese pounds per family, and each person would have one million and 100 thousand Lebanese pounds, up to five people, as a fixed amount in Lebanese pounds, despite the continuous rise in prices parallel to the depreciation of the pound.

In Jordan, fears are increasing after the World Food Program announced in mid-July that it will reduce its monthly food aid to 465,000 refugees and exclude about 50,000 other people from monthly assistance starting next August under the pretext of a funding shortfall of $41 million until the end of 2023.

Enab Baladi contacted by e-mail the office of the World Food Program in Jordan, which explained that refugee families “most in need” of food assistance will receive $21 per person per month, while families with an average need will receive $14 per person per month.

In a subsequent statement, the WFP announced the reduction of support by a third for all the 119,000 Syrian refugees in the Zaatari and Azraq camps, also starting in August, as the refugees will receive a cash transfer of $ 21 per person per month, a decrease from the previous amount of $32.

30% of adults in the two camps work in mostly temporary or seasonal jobs, and cash assistance is the only source of income for 57% of camp residents.

Syrian children on a hill above a refugee camp in the town of Bar Elias in Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley, June 13, 2023 (AP)

Underfunding policy

The Jordanian Minister of the Interior, Mazen al-Faraya, in a speech he delivered at the regional conference entitled “Waves of Migration between the Southern and Northern Coasts of the Mediterranean” on July 23, said that the financial support provided within the Jordanian response plan to the Syrian crisis amounts to 7.5% of the percentage of funding required for the first half of 2023.

Al-Faraya expects, according to information received from the UN program, to stop financial aid for refugees residing outside the camps as of early September, in addition to halting financial aid for refugees residing inside the camps as of next October.

Enab Baladi contacted the WFP office in Jordan to clarify the reasons for the lack of funding, which is estimated at $41 million.

The UN food program office stated that it relies entirely on voluntary donations to finance its humanitarian and development projects and that the reduction in the value of food aid provided by the program is not linked to the services provided by other humanitarian organizations, which have their own programs, standards, and funding to provide assistance.

In situations of funding shortfalls such as the current situation, WFP is forced to direct limited resources to try to keep assistance going to the neediest families for as long as possible.

The WFP continues to work with the Jordanian government, donor countries, and United Nations agencies to collect the necessary funding through many local, regional, and international initiatives, the office told Enab Baladi.

A previous report by Human Rights Watch (HRW), in its approach to assessing the problems of donor funding for the Syrian education file in countries of asylum in 2017, indicated that the most important reasons for the lack of funding are the lack of transparency by donors and host countries, the lack of information about donor-funded projects and their timing, and the difference among the data provided by donors regarding the amount of funding provided, and data announced by host countries or the United Nations.

The lack of funding is not a spur of the moment or specific to the current year only. In 2018, the deficit rate was 37.2% of the total pledged $3.36 billion. In 2019, the deficit rate reached 36.3%, and in 2020 the deficit rate rose to 41.9%.

The same applies in 2021 when the deficit of a total of $4.22 billion was 45.7%, and finally, last year, the deficit was 52.5% of the total of $4.44 billion pledged by donors.

What are the effects of aid cuts?

In early July, the Daraa Provincial Council published a circular on its official Facebook page stipulating that delivery periods will be delayed for a period of up to six months in some administrative units in the governorate.

The food basket is considered important for the local residents in light of the decline in purchasing power and the historic low of the Syrian pound value over the past years.

Louay Kharita, member of the Relief Committee in Daraa, who declined to be named for security reasons, told Enab Baladi that the committee had received a circular signed by the Governor of Daraa, stating that the Syrian Red Crescent branch of Daraa informed the provincial council that it had received a letter from the WFP deciding to reduce relief allocations for Daraa governorate.

This decision raised the fears of the residents in light of their reliance on the components of the basket to relieve a financial burden that would prevent them from buying it from the market for a limited period.

The basket contains five liters of vegetable oil, which currently costs 20,000 Syrian pounds, 15 kilograms of flour, three kilograms of sugar, four kilograms of chickpeas, and five kilograms of rice.

Mohammad al-Mafa’alani, of the eastern countryside of Daraa, told Enab Baladi that the divergence of delivery periods doubles the suffering of the population, especially in light of the state of poverty and the increase in unemployment, adding that the population at the present time needs an increase in aid because there are families waiting “impatiently” for them, as he put it.

Abdul-Hamid Aslan, Syrian refugee based in Jordan, told Enab Baladi that he was surprised by the extent of the reduction in the assistance he received from 207 Jordanian dinars to 90 dinars for his nine-family members, which had a “strong” impact on the family’s living condition.

Aslan fears that aid will stop completely, in light of his injury in Syria during the past years, which prevents him from working, leading to a “miserable” situation without a solution or alternative that covers this aid.

Enab Baladi interviewed several Syrian refugees residing in the camps of neighboring countries, who have similar concerns about the danger of reducing aid on their living conditions in light of the lack of existing job opportunities, most of which are unsustainable day jobs.

In her turn, the Syrian refugee Fatima al-Mafa’alani, residing in Lebanon, told Enab Baladi that cutting aid to her family will push her to return to Syria, especially in light of the security tightening experienced by Syrians in Lebanon, which deprives her husband and children of freedom of movement to find work that secures the family’s expenses.

On May 1, the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Aid (OCHA) said the number of Syrians in need of humanitarian aid is estimated at 15,300,000 people, an increase of 5% over the year 2022.

Aid cut linked to regional moves

The complexities of the Syrian file and its association for years with the regional environment and the active countries have led to the association of the humanitarian file with the political one.

This seems clear through the repeated Russian veto in the Security Council when renewing the authorization for the entry of UN aid through the Syrian land crossings with Turkey, as well as with the focus of Jordan and Lebanon and the decisions of the Arab summit meetings in the Saudi city of Jeddah on the file of the return of refugees in the wake of the rapprochement with the head of the Syrian regime, Bashar al-Assad and his return to the Arab League.

Since this return, officials from Jordan and Lebanon have held frequent meetings with officials of the Syrian regime, including al-Assad himself. The title of these meetings was the fight against drugs and the return of refugees.

These meetings coincided with the WFP announcement to cut aid in Jordan and Lebanon, and it seems that both countries may benefit, both on the political and economic levels, from this announcement to put pressure on the refugee file and their return, whether towards the regime or towards the Syrian refugees or at the international level.

The Jordanian Foreign Minister, Ayman Safadi, said on Twitter, anticipating the issuance of the WFP organization’s statement on July 13, that Jordan “will not bear the burden alone,” holding those who cut support responsible for the suffering of refugees, considering that providing a decent life for refugees is a global responsibility and the United Nations must work to enable voluntary return.”

|

The governments of Jordan and Lebanon will use the decision to reduce international aid to increase pressure on the Syrian refugees to leave their country and use them as scapegoats to explain their economic difficulties, which Lebanon has announced several times, so more restrictions on refugees can be expected. Joseph Daher – Expert in Political Economy |

On July 24, the Jordanian Minister of Interior, Mazen al-Faraya, said that Jordan is committed to facilitating the return of Syrian refugees to their country, referring at the same time to the directives of the King of Jordan to provide facilities for refugees commensurate with the aid provided to Jordan.

There are 1.3 million Syrian refugees in Jordan, according to figures from the Jordanian Ministry of Interior.

Al-Faraya also mentioned that the waves of refugees “negatively affected” the economic level in his country, calling for increased international support.

This restriction also includes the EU countries, which seem to be trying to significantly reduce the number of refugees arriving, whether from Syria or elsewhere, according to political economy expert Joseph Daher, who indicated in an interview with Enab Baladi that the European Union and Tunisia signed an agreement in this regard to prevent the flow of refugees in exchange for money no matter how this flow is stopped.

At the end of each visit of a Lebanese or Jordanian official, it is announced that the Syrian refugee file will be dealt with in the discussions with the Syrian regime and preparations for their return.

Last June, the Lebanese Minister of the Displaced, Issam Sharaf al-Din, met with the head of the Syrian regime, Bashar al-Assad, in Damascus, after which he issued statements about the regime’s readiness to receive 180,000 Syrian refugees as a first stage, according to what was reported by the Russian Sputnik agency.

The Syrian political researcher, Firas Faham, believes that both Jordan and Lebanon are already negotiating with the Syrian regime over the return of Syrian refugees within the current situation.

However, the Syrian regime will not cooperate, given that it wants to obtain direct financial funding related to the return of refugees, especially since the crises that the EU is facing in the Ukraine file prompt these countries to fear that the refugee file will become a burden on them alone in light of the decline in international aid.

A UN aid convoy enters northern Syria from the Bab al-Hawa crossing – February 11, 2023 (Enab Baladi/Iyad Abdul Jawad)

Regional push to refugee return, regime rejects

For the countries neighboring Syria, which host the largest number of them, the file of the return of refugees is one of the priorities of each government there, which appears in the form of plans or declarations issued by governments or statements by government officials against Syrian refugees.

On July 12, the European Parliament voted on a resolution calling for the continuation of aid to refugees in Lebanon, which angered Lebanese officials, headed by the Lebanese Prime Minister, Najib Mikati, during press statements on the sidelines of the Rome conference to discuss migration across the Mediterranean, considering the decision “A violation of Lebanon’s sovereignty.”

Meanwhile, the General Coordinator of the National Campaign for the Return of the Displaced Syrians, Maroun Khouli, held, in a press conference on July 13, the responsibility for the economic crisis in Lebanon on the refugees and the “sacrifices made by Lebanon,” considering that the decision of the European Parliament is unfair and “blatant interference in Lebanon’s internal affairs.

Despite the different rhetoric in Jordan, government moves and statements in this regard go in the same direction, and government decisions were issued during the past weeks restricting the work of Syrians in the kingdom.

On July 23, an internal circular was circulated through social media, issued by the Jordanian Ministry of Labor, to intensify visits to all sectors and activities in which non-Jordanian workers work, specifically the Syrian nationality.

Syrian children play soccer next to their tents in a refugee camp in the town of Bar Elias in the Bekaa Valley, Lebanon – July 7, 2022 (AP)

Last April, the Jordanian government issued a decision, published in the Official Gazette, banning several professions for non-Jordanians, including men’s barbering, sweets and pastry making, carpentry, blacksmithing, embroidery, goldsmithing, water bottling, nuts production, coffee roasting, ceramic and pottery products, and services, washing and ironing clothes.

Hiba Zayadin, senior researcher in the Middle East and North Africa Division investigating human rights abuses in Syria and Jordan, believes that decisions to reduce or stop aid can contribute to Syrian refugees’ decisions to return despite the risks.

Zayadin pointed out that the human rights organization’s successive research on refugee issues, especially Syrians, shows that there are very few people who voluntarily return despite the difficult conditions in neighboring countries and that those who return are under “enormous pressure.”

|

Despite the ongoing violations and the devastating economic and humanitarian conditions inside Syria, countries in the region and beyond continue to promote the narrative of post-conflict return. Hiba Zayadin, senior researcher in the Middle East and North Africa Division investigating human rights abuses in Syria and Jordan |

Syrian regime eyes funding

The Syrian regime repeats its demand to contribute economically to Syria in preparation for the return of the Syrian refugees. During the preparatory meetings for the Arab Summit last May, the Assistant Minister of Economy in the government of the Syrian regime, Rania Ahmed, called on the Arab countries to invest in medium and small projects in Syria, which was repeated by several officials in the government later.

The Syrian political researcher, Firas Faham, stated in his interview with Enab Baladi that the Syrian regime will not cooperate with Jordan and Lebanon in the file of the return of Syrian refugees, even if statements show the opposite, the regime wants to obtain direct international funding in this file, and its unwillingness for the return of refugees reaches the extent to arrest those who returned.

On May 11, 20 local and international organizations, including the Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR), issued a joint statement calling for stopping the deportation of Syrian refugees from Lebanon to areas of the Syrian regime where they face the risk of persecution or torture.

Faham attributes the regime’s rejection of this return to the fulfillment of certain requests it insists on, the most prominent of which is, in addition to obtaining international funding, that it directly handle the humanitarian aid file, as well as the reconstruction file, and the lifting of international sanctions on it, in order to support economic investment, which has greatly declined.

For his part, Daher believes that the Syrian regime will use the increasing pressure from Syria’s neighboring countries in the refugee file to increase normalization with it and with other countries at the regional level.

The leaks of the “Jordanian Initiative” towards the Syrian regime, published by the Saudi magazine Al-Majalla on June 25, showed that the Arab countries focused on the return of Syrian refugees within its first phase and demanded official facilitations from the Syrian regime in return for investing in areas to which the refugees are expected to return, within a “pilot project,” starting from southern Syria, on the border with Jordan.

Al-Assad had previously linked, during his meeting with the Jordanian Foreign Minister, Ayman Safadi, on July 3, the issue of the return of refugees to the deteriorating conditions in the areas under his control, stressing that the safe return of refugees is a priority, with the need to secure the infrastructure for this return and the requirements for reconstruction and rehabilitation in all its forms and support them with early recovery projects.

Syrian children play soccer next to their tents in a refugee camp in the town of Bar Elias in the Bekaa Valley, Lebanon – July 7, 2022 (AP)

War in Ukraine negatively reflected in Syria

The WFP’s announcement of reducing allocations for Syrian refugees comes due to its funding crisis, despite international pledges to provide more than $10 billion during the seventh Brussels Conference on “Supporting the Future of Syria and the Region” last June.

At that time, the countries pledged to continue helping the Syrians inside Syria and in neighboring countries, provided that the financial grants would be divided between 4.6 billion euros for the year 2023 and one billion euros for the year 2024 and beyond, while the international financial institutions and donors announced four billion euros in the form of loans, to help Syrian funding in Syria and neighboring countries hosting Syrian refugees.

The shortage of amounts announced by the WFP appears to be linked to two main factors, namely the absence of a clear political solution in Syria 12 years after the start of the Syrian revolution and the Russian invasion of Ukraine that has been going on since February 2022, which in turn constituted a global food and security crisis on the European continental level, pushing the largest percentage of donors to pay attention to their problems and reduce aid, analysts said.

The regime has sought, through various political tracks, including the Syrian Constitutional Committee (SCC), to obstruct any political solution leading to an end to the political and economic crises in Syria. In practice, this obstruction and the absence of a solution horizon leads to a reduction in aid to the Syrian refugees.

Osama al-Hafez, a researcher and political analyst, explained this point to Enab Baladi, considering that the crisis of reducing funding for the World Food Program and grants to refugees is “expectable” due to the lack of funding for refugees that will last for a long time.

The reduction process is linked to two political and economic aspects, according to al-Hafez, as the absence of hope for a sustainable political solution that will end the crisis in Syria and provide a form of long-term stability means that there will be no commitment to providing aid for a longer period.

This is due to fears of the refugee crisis turning from emergency to permanent, which cannot be tolerated by any country or international organizations for a long time, especially with the economic crisis in Europe, according to al-Hafiz, who believes that the solution to this crisis is linked to the political file.

|

Finding a long-term political solution will encourage the United Nations and donors to provide the necessary support because there is a horizon, and the situation will not last forever, while if the settlement is lame, the donors will lose hope for an appropriate solution, knowing that the solution that will keep al-Assad in power is not an ideal solution, and therefore the region will remain unstable. Osama al-Hafez – Political Analyst |

On the other hand, it seems that the influx of Ukrainian refugees into European countries in the wake of the Russian invasion and the European countries’ focus on the war there directly affected the Syrian refugee issue.

Political researcher Firas Faham believes that Europe has fears of a major refugee crisis in its vicinity and of dealing with the damages of the war in Ukraine, all of which require a high financial cost.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine led to a reorientation of international foreign aid in accordance with the political priorities of the donors.

Political economy researcher Joseph Daher pointed out that raising the Official Development Assistance from $186 billion to $204 billion means that there is a significant increase in allocations related to processing and hosting refugees within donor countries and the expansion of official development assistance to Ukraine after the Russian invasion.

The Official Development Assistance (ODA) is one of the committees of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, which acts as a forum of 31 donors and monitoring bodies and is defined as concessional financing flows to promote economic development and the “well-being” of developing countries.

Foreign aid from official donors in the Official Development Assistance rose in 2022 to its highest level at $204 billion, compared to $186 billion in 2021, as developed countries increased their spending on processing and hosting refugees and on aid to Ukraine, according to a statement issued by ODA last April.