Homs – Orwah al-Mundhir

The smuggled mobile phone markets in Homs governorate are currently a strong competitor to the govt-taxed mobile phones that are officially imported through companies licensed by the regime.

A parallel market to the regular market emerged over the 11-year conflict, which was fed by smuggling from the areas controlled by the US-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) in northeastern Syria or through the Lebanese border.

The tanks transporting oil from northeastern Syria to the Homs refinery are considered the most prominent smuggling route, as they operate under the umbrella of the al-Qaterji company, which provides its drivers with immunity when they bypass roadblocks.

The smuggling line from Lebanon constitutes a secondary factor in the process of entering smuggled mobile phones, and traders often resort to it as a result of the increase in the smuggling commission through the east of the Euphrates through tankers.

In turn, the regime’s government is prosecuting shop owners and dealers of smuggled mobile phones by raiding suspicious shops and publishing patrols to monitor those suspected of selling smuggled mobiles in Homs governorate.

Price differences, break the “IMEI”

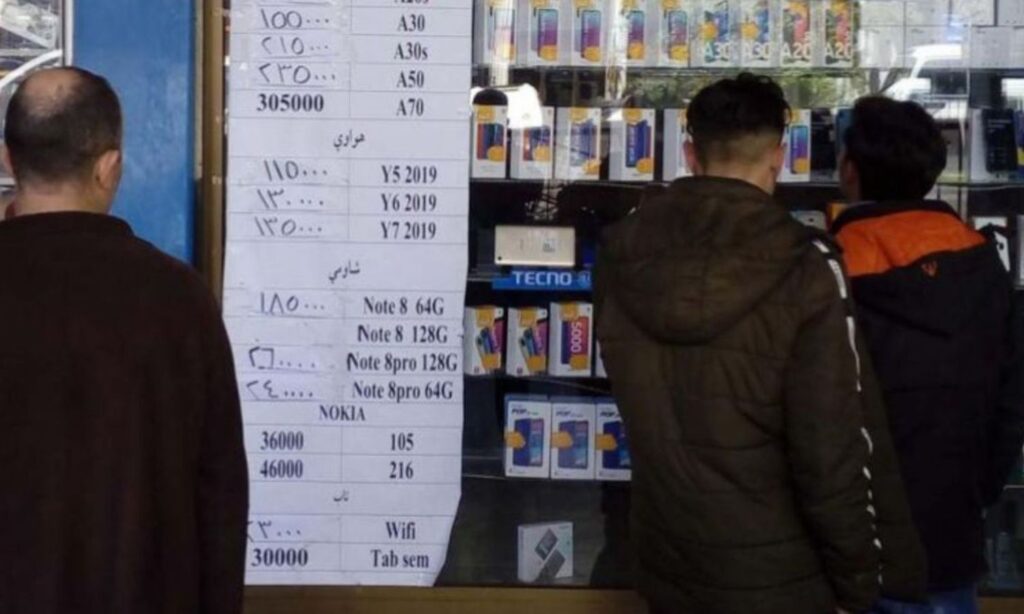

The demand for smuggled mobiles outweighs that for legally and licensed imported ones due to the large differences in prices, as the prices of regularly imported mobiles increase by about 40 percent over smuggled ones.

The only difference between the two types is the possibility of working on telecommunications networks in Syria, whose service is constantly declining in relation to the coverage and speed of the Internet.

The owner of a mobile phone store in Homs (reserved to remain anonymous due to security considerations) told Enab Baladi that the smuggled mobile phone trade is increasingly flourishing at the expense of licensed devices, explaining that despite his owning an agency for selling devices licensed by the Emma Tel company, the percentage of sales is almost zero for licensed devices, compared to smuggled devices.

The shop owner pointed out that the differences in prices are illogical, which drives most people to buy smuggled devices, which work on the network for a maximum of two months and then stop working.

The smuggled-mobile dealers offer the service of breaking the device’s “IMEI” (the International Mobile Equipment Identity unique serial number that distinguishes mobile devices and cannot be changed or erased) to ensure that it works on the communications network by downloading “Rot” programs to break the device’s protection, which allows changing the device’s protection.

This allows the device identifier to be changed in order to escape the high costs of network identification imposed by the Telecommunications and Postal Regulatory Authority.

Mahmoud, a software worker of Talbiseh town in the northern countryside of Homs, told Enab Baladi that most stores offer a “security-braking system” service and change IMEI to ensure the mobile’s work on the Syrian network.

The cost of changing the device identifier, according to its type and level of protection, starts from 35,000 to 80,000 Syrian pounds (7-17 USD), according to the device’s protection system.

Mahmoud pointed out that there are devices whose security systems cannot be broken, such as the iPhone and some Xiaomi devices, because their protection systems are complex and cannot be penetrated.

The regime’s government raised in early September the value of the customs declaration for mobile devices entering Syria without customs duties at different rates, reaching about 50 percent of the value of the cost of the device.

The customs of each device are determined based on the globally popular price, which is determined through a special price-setting system, after which the customs value is calculated, as the customs value ranges between 80,000 SYP (about 17 USD) for phones with low specifications, and about 4 million SYP (about 880 USD) for some types of high specifications.

According to previous statements by officials in the Syrian regime government, the fees for entering cellular devices are linked to the official exchange rate of the dollar set by the Syrian Central Bank.

Old phones for local network

Well-off people depend on buying old and authorized middle-class phones to use them on communication networks and to broadcast the Internet from them to the smuggled modern mobiles they carry, which do not work on the Syrian telecommunications network.

Homs-based Ghassan, who works in a private bank, told Enab Baladi that he had recently bought a “Not” mobile device from Samsung, but he is still using his old phone for communications on the cellular network and made it a hotspot for the new device.

Ghassan added that the tariff for declaring the new mobile is about 2.5 million SYP (about 550 USD). Also, he does not prefer to break the device’s protection through the “Rot” program, which pushed him to keep his old device and use it to work on the local network.

Tracking smugglers

Smuggled mobile dealers deliver devices in public squares, near bus stations, or on highways after agreeing with the customer on the price, model, and specifications of the device.

At the same time, the security forces and the police have begun to monitor and inspect anyone suspected of working in the smuggled mobile phone trade.

Omar, who sells smuggled mobile phones in Homs city, told Enab Baladi that he does not own a shop to sell mobiles, and his work is limited to selling freely through regular intermediates or phone shops in return for a commission.

Omar explained that there are members of the security and police standing near the gates of the main bus stations; their task is to monitor anyone suspicious.

The police ask for the person’s identity card and search his bag, and if any new mobile is found, it is investigated to ascertain whether the device is smuggled or licensed.

The local al-Watan newspaper reported, in early March, that the total customs revenues exceeded the amount of 113 billion SYP, during the year 2021 only, based on the data of the General Directorate of Customs.

A source in the Directorate spoke to the newspaper about a case of exploitation of economic and living circumstances practiced by some traders and smugglers, resulting from the decline in the movement of commercial activity and the regime’s policy of “import rationalization” and limiting imports to basic materials and commodities, what pushes some merchants to resort to smuggled goods.