Enab Baladi – Amal Rantisi

A year ago, the Tunisian President, Kais Saied, began a series of measures in which he sought to monopolize power by expanding his executive and legislative powers, which raises fears of a regime return to dictatorship after 11 years of the first Arab Spring revolution in Tunisia.

On any occasion since 25 July 2021, Saied used to describe his opponents as traitors and agents, saying that “those who fear dictatorship are the same ones who “commit mischief on the earth, making mischief,” in connotation to a verse from the Holy Quran, according to what he said in a speech aired on 8 July in the Eid al-Adha holiday.

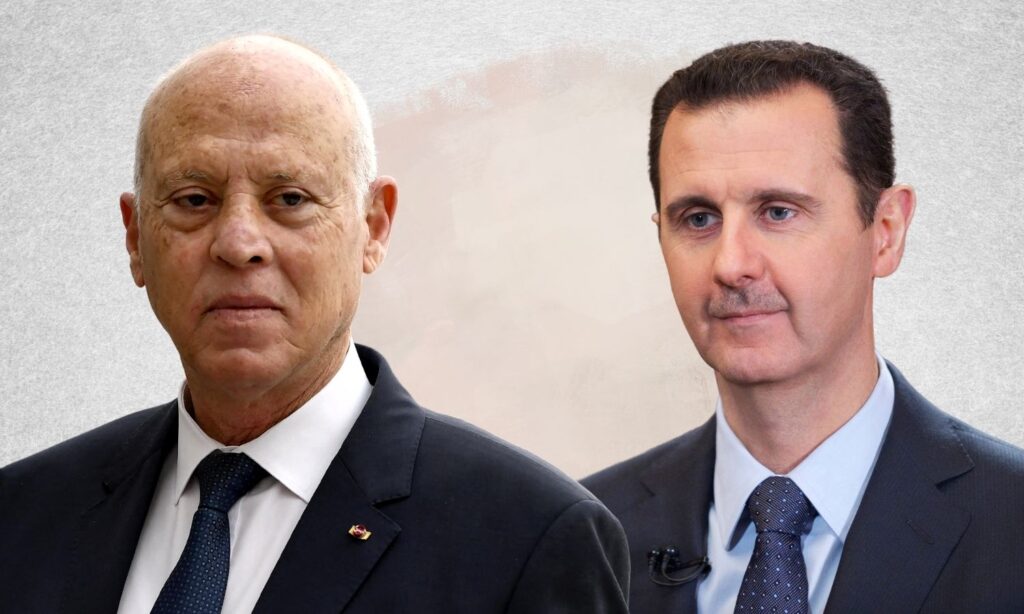

Saied’s terms belong to the same dictionary of the head of the Syrian regime, Bashar al-Assad, in his quibble to the revolution and its opponents, describing them as “scums, agents of the West and traitors.”

Saied met with the Syrian regime’s foreign affairs minister Faisal Mekdad as the pair celebrated Algeria’s 60 independence anniversary on 4 July, the state-run news agency (SANA) revealed almost two weeks ago.

Saied asked the foreign minister to convey his greetings to al-Assad, and likened Syrian and Tunisian “achievements” to one another, stating the “brotherly” countries share “common goals,” according to Syrian officials.

Enab Baladi discusses in this report the most important political changes that occurred in the relationship between Tunisia and the Syrian regime during Saied’s mandate, and the two countries’ interest in a possible rapprochement, in addition to the internal and international factors and the available approaches.

Common background, ideology

Saied called the measures he took, on 25 July 2021, “exceptional measures” that came as an outcome of a political and economic crisis triggered by the health crisis and the high number of deaths from the Covid-19 pandemic, even though some Tunisian parties described the “measures” as a “coup.”

At the time, the regime’s foreign ministry voiced support for Saied, saying, “Syria stresses the right of peoples to self-determination, and the legitimate state in Tunisia and the Tunisian people are able to move towards a future decided by the Tunisians themselves,” adding that what happened in Tunisia is within “the framework of the constitution that the Tunisian people voted on.”

Tunisia went through a series of severe political turmoil following exceptional measures that Saied began to impose, including the dissolution of parliament, the abolition of the constitutionality monitoring body, the issuance of legislation by presidential decrees, and the dissolution of the Supreme Judicial Council.

But the main hinge is Saied’s submitting a new draft constitution for a popular referendum that includes 142 articles granting broad powers to the president of the republic, in contrast to the 2014 constitution, which provided for a quasi-parliamentary system, as the first draft was described as “paving the way for a disgraceful dictatorial regime.”

Many local and international non-governmental organizations believe that the Tunisian president is alone in power and violates the principles for which the 2011 revolution took place.

Human rights organizations, including Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International, denounced Saied’s decisions and the approach he adopts towards political parties.

Regarding Saied’s approach to the Syrian regime, the political researcher at the Omran Center for Strategic Studies, Maan Talaa, believes that there is a common belief between the two parties in the narrative of “confronting the forces of darkness,” which are the forces that seek to strengthen democracy.

But for these regimes, local political interactions are classified between two options, either “terrorist” or “pro-regime,” in other words, it is a reflection of the duality of tyranny that imposes force or a police state in exchange for liberation and thus heading towards chaos, according to Talaa.

The researcher added that this is in support of rapprochement and strengthening the narrative of the Tunisian regime in the series of measures it has taken, especially with regard to the constitution, which ultimately led to the strengthening of the power of the “one man” or the dictatorial and authoritarian state in which a person tyrannizes all local authorities.

The other factor is related to the state of “nationalist partisanship,” which finds itself a trend that meets with Damascus with discourses against what is known as “imperialism” and others which is due to the necessity of having political propaganda that constitutes a lever for authoritarian rule, and here the “nationalist” factor is a common factor for a joint discourse and propaganda between the Syrian regime and the Tunisian president.

Regime interest in rapprochement with Tunisia

The Syrian regime seeks to return to the Arab incubator after 11 years through declared and undeclared normalization with a number of Arab countries, where some Arab countries such as the UAE, Oman, Bahrain, and Algeria have moved towards relations and re-recognition of the Syrian regime, while the position of some Arab countries was limited to not purifying clear support for the regime, and limited to small diplomatic representations or some commercial exchanges, in light of the EU and US sanctions imposed on it.

During an interview with the Kremlin-run RT channel on 9 June, al-Assad expressed political compassion for Arabs in general and Algeria in particular, denying the presence of political grudges against the Arab countries and considering what happened in Syria “has become a thing of the past,” noting that relations between Syria and the Arab countries have not changed in substance, but only in form.

Al-Assad also focused on the importance that Algeria gives to the upcoming Arab summit, considering that the only weight of this summit is that it will be held in Algeria, praising the stability of the relationship with Algeria since the seventies of the last century.

In regard to the regime’s interest in a possible rapprochement with Tunisia, political researcher Maan Talaa does not believe that it will make a big difference because the issue of normalization with the Syrian regime is not related to finding its external legitimacy only because this legitimacy, in the end, is linked to an American and European veto, which makes any normalization step restricted to narrow political approaches, up to this moment.

Reading the common interests between Syria and any country now comes within a deeper perspective than that of diplomatic formation, representation, or recognition, and what the Syrian regime needs now is to lift the sanctions and lift the red lines on reconstruction, and thus remove the sanctions and engage more in the international community with the post-war challenges, Talaa says.

He added that this helps the regime to overcome the internal crisis, but all attempts at diplomatic representation remain within formal frameworks if it is not accompanied by a developmental trade and economic movement.

Russia, a common factor

Russia is a common factor between the key ally, the Syrian regime, and most of the countries that support it. At the level of the Maghreb countries, Algeria is known as Russia’s “strategic and historical ally.” It also voted with the Syrian regime against the decision to suspend Russia’s membership in the United Nations Human Rights Council.

In April, Tunisia’s ambassador to Moscow, Tarek Ben Salam, told Russian news agency Sputnik, “we are now working to ensure the Tunisian president visits Russia as soon as possible,” The New Arab newspaper reported.

But the expected visit was later denied by the Tunisian ambassador to the Congo, Adel Bouzekri Rmili, who tweeted on his official account on 28 April, “I just checked with my colleague in Russia, and he told me that is not true! He just said he intended to develop bilateral relations through “high-level visits” while highlighting the importance of the training of the first astronaut.”

He also said that “Russia is still a historical partner for Tunisia in several fields, and it is natural for the ambassador to hope for the development of Tunisian-Russian relations, and indeed it is his duty to work on this.”

According to The New Arab, “A number of activists in coordination groups supporting the Tunisian president defended the news of the announcement of the visit, considering that it will strike new balances for the benefit of Tunisia as it heads east towards strengthening its relationship with Russia, that would stop a series of Western warnings criticizing the political path approved by Saied in Tunisia,” especially after the US administration criticized Saied for his seizure of power.

On 11 May, al-Quds al-Arabi newspaper published photos showing Saied’s supporters in gatherings, carrying Russian flags and al-Assad portraits.

Analyst Talaa told Enab Baladi that the Tunisian approach comes within the policy of managing axes, especially that the forces that support or are in alliance with Russia aspire with their imagination to reach the formation of an eastern axis that balances the western axis and thus returns the regional political scene to the stage of the Cold World War.

Saied’s announced visit may come to manage the balances in Tunisia’s relationship with international powers, especially since the stability or reconfiguration of the international system is now linked to the Russian war on Ukraine and its repercussions and outcomes.

“This is why this approach to Moscow makes Tunisia have multiple options, not only options related to regional countries or the US and the EU,” says Talaa.

The major message in all these moves by the Tunisian president is to build a system for an authoritarian state in which the president controls the keys to local authority and maximizes his legislative, judicial, and security powers, according to the researcher.

In the end, this enhances the chance of him staying in power by narrowing the spaces of action for the forces opposing him inside Tunisia, and he has an example in the Egyptian model, and the Syrian model is another example, Talaa adds.

In general, Tunisia’s move towards the Syrian regime does not constitute a feasible path in the foreseeable future, which is reflected in the feasibility and effectiveness of the Syrian regime itself because it is linked to the questions of the regime’s internal renaissance, according to Talaa.

These questions are related to US and EU sanctions that prevent the regime from responding to post-war crises and the continuation of economic and local development deterioration, and this is an obstacle at the level of reconfiguring the internal structure of the Syrian regime and its local networks again, and thus continuing the idea of a failed state, he concluded.