Saleh Malas | Zeinab Masri | Diana Rahima

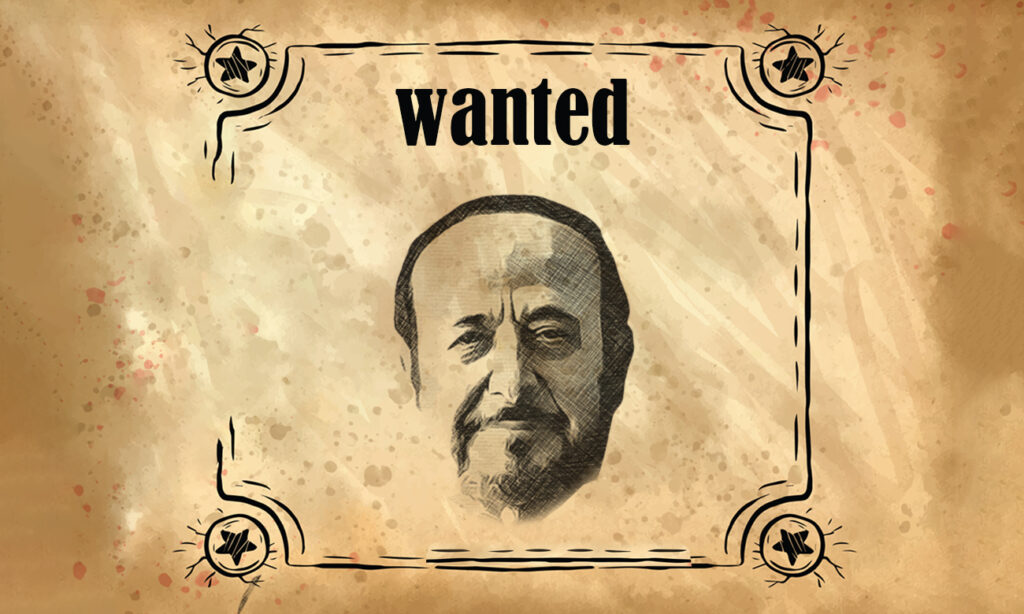

While the legal debate on how Rifaat al-Assad, the uncle of Syrian regime president Bashar al-Assad, has managed to flee France to dodge arrest continues, media outlets and social media platforms have exploded with news over the past days about his return to Syria after four decades in exile.

The French and Western media reported conflicting information about Rifaat al-Assad’s escape method from France. However, French journalist Georges Malbrunot, who is experienced in Syrian affairs, presented a shocking revelation that Rifaat did not escape but left France in a deal thanks to past services he made to the French intelligence services.

Some media reports said that Rifaat’s return was to prevent an imprisonment term in France and described Syria as a “haven for criminals fleeing justice.”

Rifaat’s return to Syria brings back to Syrians’ memories hundreds of narratives about his role as the commander of Saraya al-Difaa (Defense Brigades), which targeted Islamist opponents to Hafez al-Assad’s rule in Hama city and his responsibility for the Tadmur prison massacre in the 1980s.

Rifaat’s escape has brought criticism to France for allowing him to leave the country, while some directed their critique to the Syrian opposition and Syrian human rights organizations for failing to prosecute Rifaat al-Assad, the godfather of human rights violations in Syria, or provide evidence against him.

In this in-depth article, Enab Baladi talks with lawyers, legal experts, and Syrian opposition figures about how Rifaat al-Assad managed to return to Syria and why he was not held responsible by human rights organizations who could file criminal lawsuits against him. It also tackles France’s entitlement to claim Rifaat back in the event of any court ruling incriminating him for war crimes or crimes against humanity, in addition to Interpol’s stand on this matter.

A “dramatic blow” to accountability efforts

How did Rifaat al-Assad escape France?

After nearly 40 years in exile, Rifaat al-Assad dubbed the “Butcher of Hama,” escaped France to Syria to avoid a jail term after the Paris Appeal Court sentenced him to four years in prison.

On 8 October, the pro-government local newspaper al-Watan said that Rifaat had arrived in Damascus to avoid imprisonment in France, following a court ruling and the seizure of his assets in Spain. The newspaper added that Bashar al-Assad “has overlooked everything his uncle had done and allowed him to return to Syria like any other Syrian citizen, but with strict regulations, and no political or social role.”

A day after a court ruling was issued against Rifaat al-Assad, his son Ribal shared a video showing his father doing the “dabke” dance with his two grandchildren, Rifaat junior and Kaisar. On 11 September, Rifaat’s second son, Somer, said in an interview with the Russian news agency RIA Novosti that accusations against his father are “politicized and fabricated.”

On 9 September, the Paris Appeal Court backed a guilty verdict against Rifaat al-Assad for accumulating assets worth about 90 million euros in France, including townhouses, a stud farm, and a chateau with ill-gotten-gains.

The 84-year-old former Syrian vice-president, who has lived in exile since 1984, was convicted of money laundering, embezzlement of Syrian public funds, and aggravated tax evasion and will have his real estate assets confiscated by law.

However, the verdict against Rifaat was not implemented in France because Rifaat’s lawyer appealed the court ruling within 48 hours following the sentencing, political writer and Syrian lawyer in France Zaid al-Azem told Enab Baladi.

Al-Azem said that a penal sentence in France would only be carried out when it becomes final and imperative, adding that had the Cassation Court issued a final rule in Rifaat’s case, he would have been forced to stay in France.

The French government released no information about the way Rifaat al-Assad left France, which prompted lawyers and human rights activists to demand answers from the French Ministry of the Interior on this issue.

“It is possible that the French themselves do not know how he escaped, as he may have fled France with the help of Britain,” al-Azem said.

The French newspaper Le Figaro published on 14 October that Rifaat left France thanks to previous services he made to the French Intelligence.

The writer of the Lefigaro’s article, Georges Malbrunot, said that Rifaat has previously made services to Pierre Marion, the director of the French Intelligence in 1982, where his services “played a significant role in the exposure of Sabri al-Banna (Abu Nidal) network after it carried out bombings in France.

According to Malbrunot, the Syrian authorities wish to utilize Rifaat’s sons’ relations with the European mafias and that the relationship between Rifaat’s son, Somer al-Assad, and Bashar al-Assad’s brother, Maher, was never disrupted.

In all cases, the French Interior Ministry is responsible for Rifaat’s escape from France, as he was under receivership and was prohibited from leaving the country, al-Azem said.

In a statement issued on 11 October, the French organization Sherpa, which defends victims of financial crimes and is responsible for prosecuting Rifaat al-Assad, called his escape a “dramatic blow” to France’s efforts to fight transnational corruption and an “alarming signal” about France’s commitment to the anti-corruption fight.

In the statement, Sherpa said, “We question the conditions that made Rifaat’s escape possible, which constitutes a failure on France’s part to meet its international commitments to fight and punish corruption effectively.”

Sherpa added that the return of Rifaat al-Assad to Syria and his reception by the current Syrian president demonstrates that it is urgent that the framework for the restitution of assets put in place by France considers the risk that the returned assets will fall back into the corruption circuit.

The organization called on French President Emmanuel Macron to withdraw the Legion of Honour from Rifaat al-Assad, who received it in 1986 and still holds it till today.

No need to file new lawsuits against Rifaat al-Assad

Al-Azem pointed out that there is no need to bring new cases against Rifaat al-Assad, with the presence of far more important lawsuits filed against him before Swiss courts pertaining to his involvement in the 1982 Hama massacre and the Tadmur prison massacre in the 1980s, in addition to money-laundering and tax evasion cases in France.

Besides, France does not need to circulate an arrest warrant against Rifaat al-Assad among the European Union (EU) countries, for he would be arrested and deported to France in case he was busted in any EU country under the European arrest warrant (EAW).

Al-Azem added that the arrest issue of Rifaat al-Assad had become more complicated. Hypothetically speaking, Rifaat would not serve any final sentence by the Swiss judiciary for being a fugitive criminal in Syria.

This problematic situation requires focusing on the possibility of enforcing previous sentences of currently valid cases instead of bringing out new cases against Rifaat al-Assad.

According to al-Azem, the Syrians themselves are responsible for Rifaat’s state as a free man. They fell short in bringing him to accountability, as they did not take any legal action against him since he left Syria. The only time Syrians took moves against Rifaat was after the eruption of the popular uprising in 2011 when a group of Syrian legal professionals and activists started bringing up past crimes.

Lawsuits raised against Rifaat al-Assad before 2011 were “weak” and did not receive serious financial, moral, or legal support, al-Azem said.

When asked about the difficulty of building a case against Rifaat al-Assad in terms of providing evidence and witness statements incriminating him of war crimes, al-Azem said that it is a difficult matter with limited access to evidence (video recordings or photos) and testimonies against Rifaat.

The Syrian people know that Rifaat is responsible for the Sednaya and Tadmur prisons’ massacres, but there is no hard evidence or confessions from regime officers or elements to prove his criminal involvement.

Al-Azem talked about one incident in 1981 when Syrian officers confessed under investigation that they planned to assassinate Jordanian Prime Minister Mudar Badran. During the same investigation, the officers said that Moein Nassif, Rifaat’s son-in-law, ordered the Sednaya prison massacre, but they gave no information about Rifaat’s involvement.

These incriminating confessions entail the immediate arrest of Moein Nassif once he steps foot in Europe.

Al-Azem said that there is no visual evidence of the Hama massacre, except with the British/Irish journalist Robert Fisk who witnessed the massacre and took photos of the devastated city, but he died without sharing them with the world.

Al-Azem mentioned that there were attempts to reach Fisk between 2014 and 2015 to get access to the Hama photos he took, but to no avail.

Fisk is one of the few Western journalists to witness the Hama massacre carried out by the Syrian army under the rule of former president Hafez al-Assad. At that time, Fisk was a correspondent for the British Times newspaper in Lebanon, who had the chance to visit Hama during the time of the massacre.

The Middle East correspondent Fisk wrote a lengthy article about his version of the Hama massacre events in his book, “Pity the Nation.”

Legal or political factors?

How did Rifaat al-Assad escape criminal penalties in Europe?

There were attempts by international organizations to bring up (ill-gotten-gain) financial cases against Rifaat al-Assad, with charges of corruption, tax evasion, and embezzlement of public funds.

Meanwhile, there were very few and humble attempts by Syrian and international human rights organizations to build a criminal case against Rifaat inside the EU while he was still living there.

Several legal and political factors prevented the enforcement of criminal penalties on Rifaat al-Assad.

Rifaat’s return to Syria this October shocked many Syrians who resorted to social media platforms asking why Rifaat was not held accountable for his crimes during the 20 years or more he spent in Europe.

Since 2014, several EU countries have witnessed court cases bringing together Syrian victims and war criminals under the principle of universal jurisdiction, a primary tool for prosecution in cases of war crimes and crimes against humanity.

The principle of universal jurisdiction is relatively recent in European law. It was first introduced into the legal systems of EU countries in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

Since adopting this principle, Syrian human rights organizations have tried to work on the file of Rifaat al-Assad’s war crimes, the lawyer and director of the legal office of the Syrian Center for Media and Freedom of Expression (SCM), Tariq Hokan told Enab Baladi.

Hokan said that any human rights advocate agency wishing to open the file of Rifaat al-Assad’s war crimes must know in advance that it will have to search into details of crimes committed 40 years ago in circumstances very different from those of today. Back then, people did not have fast communication tools, nor could they document war crimes; that is why “we faced great difficulties finding witnesses, and when we did, they refused to cooperate in many cases,” Hokan said.

Syrian and international human rights organizations, including the SCM and the Syrian Center for Legal Studies and Research, are trying to bring justice to victims of human rights violations committed by the Syrian regime and its breaches of the international humanitarian law inside European courts, particularly in Germany, Sweden, and France.

For any international war crime or crime against humanity case to reach a European court, it should go through a legal procedure starting with preliminary investigations on those suspected of human rights violations. Then, the court views the case to see if it is within its jurisdiction. When accepted, the legal body behind the case must provide strong evidence, including visual proof and testimonies; otherwise, the case would be weak.

Each case within the jurisdiction of the European courts relating to the human rights file in Syria carries a great deal of legal evidence that sets the stage for the prosecution of suspects of war crimes in Syria.

The legal evidence is presented to the court prosecutor as indisputable evidence, besides reports issued by functionally, professionally, and legally authorized bodies under the International Rules of Procedure and Evidence. These legal proofs confirm criminal charges against individuals administratively linked to the Syrian regime government or other perpetrators of violations on Syrian territory.

The claim that Syrian human rights organizations did not make efforts to hold Rifaat al-Assad or other individuals of high military ranks accountable before European courts is unfair and distant from reality and international laws, Hokan said.

He added that the principle of universal jurisdiction is limited by immunity, as states’ heads are immune from prosecution.

Aside from presidents, all officials can be prosecuted under the universal jurisdiction principle. In Germany, the Chief of the Syrian Air Force Intelligence Directorate, Jamil Hassan, had an arrest warrant issued against him by German judicial authorities. In France, Chairman of the National Security Bureau Ali Mamlouk and the Head of the Investigation Branch of the Air Force Intelligence Directorate Abdulsalam Mahmoud were named in international arrest warrants by French authorities.

Other Syrian regime’s officials responsible for horrific violations will be brought to justice, Hokan said.

The 2018 arrest warrants issued by French courts against the regime’s three officials were triggered by the Caesar photographs. In 2013, a dissident Syrian intelligence officer leaked 50,000 photographs showing torture and starvation victims of Syrian regime prisons.

In Syria’s war and human rights crimes cases, the prosecution requires suspects’ physical presence in the European country where the trial is held. This requirement is a sine qua non in most legal systems acknowledging the principle of universal jurisdiction.

According to Hokan, the investigation file of Rifaat al-Assad’s crimes before Swizz judicial authorities has come a long way.

He added, “The legal grounds on which the case against Rifaat al-Assad is built might change now that he has returned to Syria, for Switzerland requires the physical presence of the suspect on its territories to continue criminal proceedings. But no matter how the situation evolves, we will continue legal proceedings against Rifaat al-Assad, the godfather of war crimes and crimes against humanity perpetrators in Syria.”

In September 2017, the Swiss TRIAL International organization filed a criminal complaint against Rifaat al-Assad following a thorough investigation, on which Swiss judicial authorities charged him for his role in the 1982 Hama massacre and the 1980 Tadmur prison massacre.

This case dates back to December 2013, when the Geneva-based non-governmental organization TRIAL discovered that Rifaat al-Assad was staying in one of Geneva’s luxury hotels discussing Syria’s future, two years after the beginning of the Syrian revolution against his nephew, Syria’s incumbent president, Bashar al-Assad.

“We did not ignore Rifaat al-Assad’s crimes”

During the legal proceedings held in Switzerland, a witness made a testimony before the prosecutor last July, the Director of the Syrian Center for Legal Studies and Research, lawyer Anwar al-Bunni, told Enab Baladi.

“The witness confirmed the presence of Rifaat al-Assad in Hama during the city’s 1982 massacre. Rifaat’s lawyers were present during the hearing of the witness’s testimony, whom they questioned thoroughly about his statement,” al-Bunni said.

In April 2020, Syrian and international media and human rights advocacy organizations clamored with news of Syrian officials’ trial in Koblenz city in western Germany for crimes against humanity in the regime’s detention centers in Damascus.

A German judge convicted Eyad al-Gharib and sentenced him to four and a half years’ imprisonment for complicity in crimes against humanity, while the prime suspect, Anwar Raslan, remains on trial pending the hearing of witnesses’ statements.

“We did not ignore Rifaat al-Assad’s crimes to focus on inferior Syrian officials. We continue to build a case against him since 2014, but the search for witnesses able to make a statement is difficult, and there are attempts to continue prosecuting Rifaat in absentia in Switzerland, al-Bunni said.

The Syrian political opposition in Western countries and human rights organizations are responsible for Rifaat al-Assad’s escape from prosecution in Europe during his extended stay there, former spokesperson of the Muslim Brotherhood and the director of the Asharq al-Arabi Center, Zuhair Salem, told Enab Baladi.

In 1982, Rifaat launched his offensive against the Muslim Brotherhood movement in Hama city, which led to the killing of nearly 40,000 people, Salem said.

“There have been attempts to prosecute this man (Rifaat al-Assad) for crimes against humanity, but the European courts are governed by higher policies no matter how impartial their judicial decisions may be, preventing the opening of Rifaat’s war crimes file,” Salem added.

“The legal requirements of European courts are unattainable,” Salem added in the context of legal action raised against Rifaat al-Assad.

“Rifaat dodged accountability even after being named in many cases thanks to political reasons or courts’ rejection of evidence and witnesses’ testimonies. In addition, the lack of photos or videos proving Rifaat’s responsibility for war crimes in Syria has helped him escape justice,” Salem said.

According to Salem, the director of the Syrian Human Rights Committee (SHRC) and member of the Muslim Brotherhood, Walid Safour, tried to bring a legal case against Rifaat al-Assad and join the prosecution’s side as a witness. “However, our inability to meet legal requirements necessary for the success of previous cases, alongside political constraints, have prevented us from securing a verdict condemning Rifaat al-Assad,” Salem said.

Rifaat’s case is part of bigger “political settlements”

Samira Moubayed, a member of the civil society delegation within the Syrian Constitutional Committee (SCC), told Enab Baladi that the failure of the Syrian opposition to bring legal proceedings against Rifaat al-Assad could be attributed to two factors.

The first factor is the “inclusion of Rifaat al-Assad’s case into Syrian political settlements between several parties, including the regime and the opposition, mainly the Islamic political movement. These settlements are conducted under certain political perspectives and power-sharing objectives, with no regard to the victims’ rights or those of their families and relatives,” Moubayed said.

The second factor is “international settlements and bargains pertaining to political trends that existed and supported the Syrian regime in the past era for the ‘maintenance of security and stability in the region’ attitude, which is now undergoing radical changes,” Moubayed added.

Opinion poll

Enab Baladi conducted an opinion poll on its social media platforms and official website on the reasons that prevented the Syrian opposition outside Syria from prosecuting Rifaat al-Assad.

The poll was answered by 929 persons, of which 616 said that the reasons are related to the opposition’s focus on side issues, while 313 participants said that cases like that of Rifaat al-Assad need compelling and sufficient evidence to be completed.

Syria is not bound by extradition treaties

No intention to surrender Rifaat al-Assad to France

Article 38 of the 2012 Syrian Constitution provides that “A Syrian national may not be extradited to any foreign party,” meaning that Syria is not bound to hand over Syrian criminals fleeing accountability for crimes against humanity.

Law No. 53 of 1955 containing provisions for the extradition of ordinary criminals says, “In the absence of international conventions that have the force of law in Syria, the provisions for the extradition of ordinary criminals and those prosecuted in court for ordinary crimes and their effects shall be subject to the provisions of this law and Articles 30 to 36 of the Syrian Penal Code. These provisions apply to all cases not regulated by international conventions.”

The extradition of criminals between two countries must meet a set of conditions to be acceptable, including that the act for which extradition was requested be a misdemeanor or a felony for both countries.

However, the Syrian regime government did not release any statement incriminating Rifaat al-Assad for war crimes or crimes against humanity during his service as a military or political official in the last century.

A Damascus-based lawyer told Enab Baladi that if a Syrian national was charged with a felony punishable under Syrian law, the Syrian state could try him or her in national courts.

If the person to be extradited was not Syrian and the felony he/she committed is punishable under Syrian law, the Syrian state can extradite them to a country with which it has an extradition treaty or to the International Criminal Police Organization (Interpol).

Many foreign nationals who committed criminal acts in their countries before coming to Syria were extradited within legal regulations.

In 1983, Syria ratified the Riyadh Arab Agreement for Judicial Cooperation between States of the Arab League. This agreement is one of the extradition bases in the Syrian law, in addition to a series of bilateral agreements between Syria and some foreign and Arab countries.

|

A person is a fugitive from justice where he/she is charged or convicted with an extraditable offense in the demanding state. Extradition is the surrender of an alleged criminal, usually under the provisions of a treaty or statute by one authority (such as a state) to another having jurisdiction to try the charge. |

Interpol: Rifaat al-Assad’s extradition is a national decision

Enab Baladi emailed Interpol about its possible arrest of Rifaat al-Assad, to which it responded, “the Interpol General Secretariat does not conduct investigations itself, and its officials do not have any powers of arrest.”

“If an individual is wanted for prosecution or to serve a sentence, the member country which is investigating that person may request the Interpol to issue a Red Notice based on a valid national arrest warrant.”

“A Red Notice is not an international arrest warrant, it is a request for international police cooperation sent to member countries’ law enforcement agencies to locate and, in accordance with the national laws of the member country, provisionally arrest a person pending extradition, surrender, or similar legal action.”

“A decision to arrest and or extradite, or not, an individual subject to a red notice is a matter for the competent national authorities,” the Interpol told Enab Baladi.

“The Interpol cannot demand that action be taken on a Notice, and whether to do so is completely within the discretion of each country.”

According to the Damascus-based lawyer, Rifaat al-Assad enjoys a broad popular base among the regime’s loyalists, and the possibility of him representing a danger to Bashar al-Assad’s regime or leading an opposition activity against it is unlikely.

Rifaat’s old age and subjection to control will prevent him from making a move against the regime in Syria, the lawyer said.

The head of the Syrian Legalists Committee, judge and chancellor Khaled Shihab Eddin, confirmed that the text of the Syrian Penal Code prohibits the extradition of Syrian nationals, whatever the crime they have committed, and in whatever territory. By law, Syria can prosecute any fugitive criminal, as in the case of Rifaat al-Assad, who could be trialed under a file submitted by France, clarifying facts and evidence and everything relating to the crime for which he was punished.

Shihab Eddin added that Syria will refrain from handing over Rifaat al-Assad, and France will not demand his extradition, as it could have prevented his escape in the first place, but did not do so.

Any extradition request from France would require communication with the Syrian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and would be looked at as an official acknowledgment of the regime or a normalization of relations with it, thus a victory for the regime’s diplomatic relations with France.

Under Syrian law procedures, the demanding state must submit a request to the Syrian authorities by diplomatic means through the Syrian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The ministry would then transmit the request together with the extradition file to the Ministry of Justice, which would forward the request to the Extradition Commission.

The Extradition Commission is headed by the Deputy Minister of Justice and two judges appointed by an official decree and has all the powers of investigating judges, such as questioning, arresting, and releasing wanted persons.

Spanish authorities seizing Rifaat al-Assad’s assets under operations linked to an investigation in France on charges of misappropriation of public funds and money laundering – 4 April 2017 (AFP)