Enab Baladi – Saleh Malas

“We spent 30 years building our house to bring the family together and create memories. Years went by abroad until we could return home and settle down. Then, in a single moment, all was gone, and we found ourselves at the beginning of a new tiring journey. Once again, we left our home country searching for a new life.”

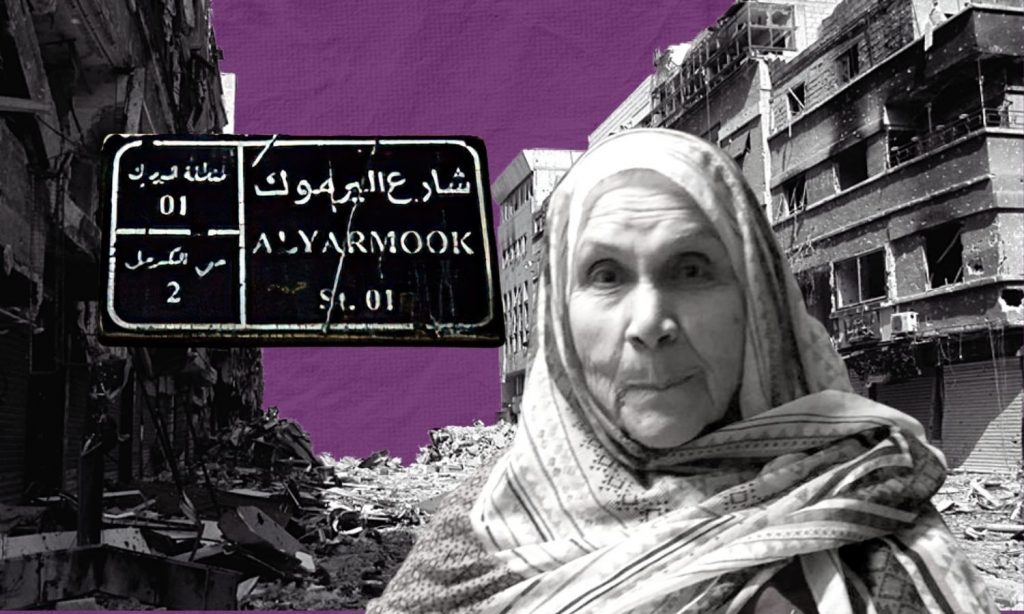

With these words, Rihab Qassem (aged 65) recounted to Enab Baladi her daunting life journey spent in search of stability in someplace where human dignity is respected while going through many tragic detours and surviving their destructive psychological effects.

In December 2012 and after Syrian regime forces bombed her family house, Rihab fled the Yarmouk camp area in southern Damascus, with her sons who were prosecuted by the regime’s security services.

“We did not take sides. We only treated people injured by bombardments,” Rihab said. In October 2013, Rihab took her last look at her house’s destroyed walls, captured some photos for memory, and embarked on a new journey seeking refugee in Europe to reach Denmark eventually.

Threats of deportation

In early 2014, Rihab was granted a residency permit in Denmark under humanitarian protection grounds. Her house in the Yarmouk camp was completely destroyed during the battles, ending any dream of returning home.

Despite being permitted residency in Denmark, Rihab’s story was far from reaching a happy ending, as Danish authorities issued a report in 2019 saying that the security situation in some parts of Syria has “improved markedly.”

The same report was used as a pretext to start reevaluating hundreds of residence permits granted by the Danish government to Syrian refugees coming from the Syrian capital of Damascus and its surrounding areas.

Last July, Rihab was handed over the Danish Immigration Service’s decision of deportation from Denmark on the grounds that Damascus is reclassified as a “safe zone.”

“A house’s value is nothing when compared to thousands of people’s loss of loved ones during the war in Syria, and even if I wanted to go back home, do you think there is any chance for me to return to my house? There is not,” Rihab said.

Speaking of her house, Rihab shows zero hope of returning home, knowing that the Yarmouk camp is in ruins and its streets are empty with nothing but destroyed houses.

Syrian government’s property laws destroy hopes of returning home

In the last ten years, the regime’s government issued several laws and legislative decrees and some administrative decisions that adversely affected house, land, and property (HLP) rights of Syrian citizens in general and Syrian refugees in particular.

The government HLP regulations have created additional burdens and challenges for Syrian refugees seeking to deprive them of their property rights.

Legislative Decree No. 66 of 2012 is one of the laws threatening the HLP rights of Syrian citizens. It stipulated the establishment of two zoning areas within Damascus province to achieve urban development in informal settlement areas.

Syrian lawyer Hussam Sarhan told Enab Baladi that properties included in the zoning area are viewed as common property between a group of property holders. Each group member has a share equal to the estimated value of his/her property or rights in rem.

Sarhan said that under the decree, the zoning area serves as a legal personality incorporating all rights holders and is represented by Damascus province, while real estate transactions (sell, purchase, or donations) for properties included in Decree No. 66 two zoning areas are banned.

According to Sarhan, Decree No. 66 constitutes a significant threat to Syrian refugees’ property rights as it grants them a short period of 30 days starting after the announcement date of the decree to claim ownership. During this period, absentees outside Syria must submit an application after choosing a place of residence within the zoning plans’ boundaries in Damascus province attached with legal documents.

He added, the fact that many property owners were forced out of Syria like Rihab Qassem, who cannot return to her country due to security concerns, makes absentees’ HLP rights at risk of being violated under the decree.

According to the lawyer, Decree No. 66 does not guarantee accurate estimation of properties’ value, including building structures, trees, and crops, affecting the final valuation of these properties.

The decree ignored the Syrian government’s acknowledgment of some slum areas like the Yarmouk camp when it provided its residents with necessary infrastructure services and regarded them as areas of building violations that must be regulated in zoning plans.

The decree stipulated that residents of informal settlements included in zoning plans are only entitled to the cost of their properties’ rubble built on public or private state property.

In June 2020, Damascus Provincial Council held a special session in which it announced the approval of the Yarmouk camp’s regulatory map before sharing it with the public. Soon later, the Council opened the door for objections and received thousands from the camp’s residents.

Many Yarmouk camp former residents saw the new zoning plan as a threat to the camp’s identity and status as a symbol of return to Palestinian refugees in Syria. Fears of demographic changes also prompted objections.

Decree No. 66 paved the way for the issuance of Law No. 10 of 2018, which also gave a short notice of 30 days to rights holders to claim ownership. Later, the law was amended, and the objection period was extended to one year, starting after the announcement date of the zoning plan.

In 2015, the regime government passed Law No. 23 on planning and urban development. The law aimed at creating zoning areas with legal personality.

Law No. 23 allows administrative units such as municipalities and governorates to expropriate informal housing areas located within zoning areas. As a result, owners of informal housing would lose their independent ownership in favor of having shares in a common property that would be divided into plots under the supervision of real estate distribution committees.

Several factors impede the return of Syrian refugees in Europe or other parts of the world to their homes, chiefly the absence of any legal instruments that would help them restore their properties or receive compensation, Sarhan said.

He added that another factor complicating Syrian refugees’ return is the Syrian judiciary’s lack of impartiality, independence, and fair trial standards.

According to Sarhan, the Syrian government has its own policy managing Syria’s real estate problem in its best interests. It exploits the problem in different ways instead of finding solutions to it.

“A living nightmare”

Syrian regime forces started bombing the Yarmouk camp on 16 December 2012 in what was known as the massacre of the Abdul Kadir al-Husseini Mosque and the Fallujah School, leaving more than 200 persons killed or injured.

The bombing caused the displacement of more than 80 percent of the camp’s residents to other areas inside Syria or abroad. Those who remained suffered from a siege imposed by regime forces between 2013 and 2018, with the participation of allied Palestinian militias.

A report by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) mentioned that millions of Syrian refugees are distributed over more than 120 countries, while Syria’s security and economic situations remain a discouragement for any return.

“Houses are murdered with the absence of their residents,” These meaningful words said by the famous Palestinian poet and writer Mahmoud Darwish best describe the conditions of Syrian refugees’ houses whose owners left Syria with no hopes of returning to claim back their property rights.

As for Rihab, she told Enab Baladi that this period of her life has been a living nightmare as she did not achieve the stability that she has been working so hard for decades to achieve.

Rihab intends to fight for her and her family’s right of protection and residence in Denmark by attempting to file a lawsuit before relevant local courts.