A shift has been marking the dynamics of the educational process in Northern Syria, as a group of Idlib University students chose to contribute to the process themselves, refusing to be passive recipients. Some of these students decided to put their skills and knowledge into practice and volunteered to train their colleagues; others held discussions and seminars to exchange expertise and widen their horizons. Both approaches granted students access to application beyond the limitations of theory.

Training classmates and non-student applicants attracted the attention of dozens of male and female undergraduates from different universities in northwestern Syria. “They wish to influence society,” head of the Khuttwa Training Team (Step), Muhammad Da’boul told Enab Baladi.

These student-led training programs cover a variety of fields: arts; languages; literature; computer skills; psychological support; protection and healthcare awareness; first aid and nursing.

It was a student initiative that started the project seven moths ago. Four students of Idlib University offered to teach their classmates Turkish language and provide them with drawing lessons. Soon, many students joined the group, which consists of 70 male and female students today.

At first, training was Internet-based, held via Zoom, or WhatsApp. Nearly two and a half months later, student trainers shifted to in-person teaching. They rented centers and charged applicants a “nominal” fee to cover logistics and stationery, Da’boul reported, who is a third-year student in the department of Arabic Language and Literature.

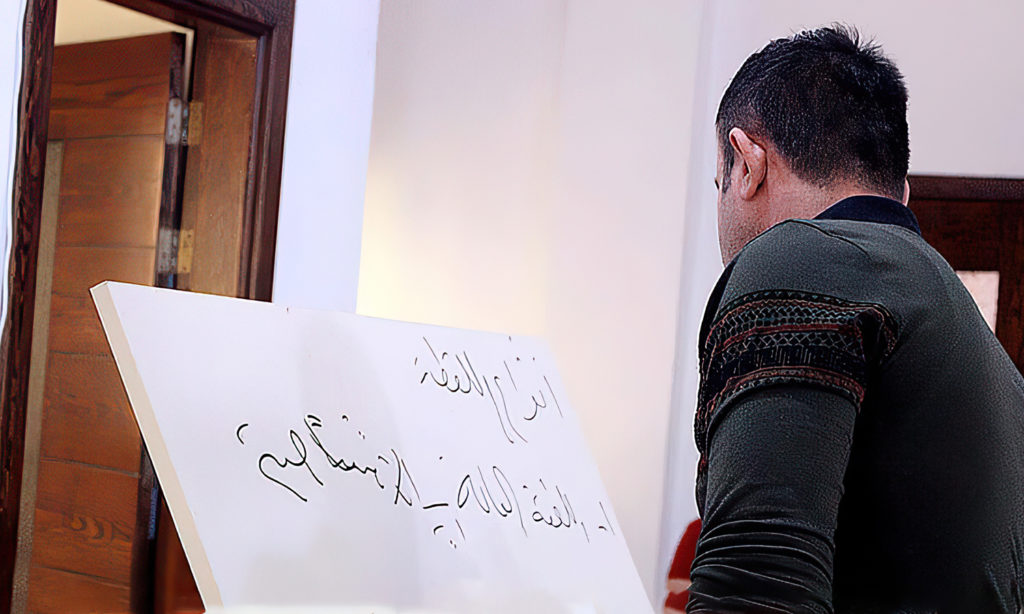

“You are students, not academics; you are not qualified to offer such trainings,” Da’boul said, describing the recurrent criticism laid by detractors against the initiative.

It was not only criticism that hampered the students/trainers’ efforts but also the lack of accommodation at the beginning. Still, the team plans to overcome this hurdle and to hold its first all literature seminar, with a focus on short stories; prose; and monologue.

Students also plan to expand their programs’ scope and conduct professional training for women in Idlib city, its suburbs, and the Aleppo countryside.

“We Can”

Khuttwa’s target group was initially fellow students, but the team welcomed all the applicants who searched for a means to develop, train, and build their capacities.

Da’boul said it was not the lack of services or education materials that made students embark on this experience, but it was that “as students, we discuss better, and can communicate information easier,” Muhammad told Enab Baladi.

Other than logistics, the students’ lack of practical experience poses a challenge to the initiative.

University curricula are extensive but still do not cover courses such as arts. Inas Darwish, a second-year business administration student, attempts to address this gap. She uses her talent to create drawing videos for her classmates.

“I have a passion for teaching drawing,” said Inas, who is also one of the student team’s founders. “Training was fun and difficult because we still cannot offer trainees in-class sessions. We still do not have a place to offer physical training. Without unmediated contact and body language, ideas are not completely channeled.”

Unlike Inas’ situation, it was the lack of practical experience that prompted a group of students at the Technical Institute of Media at the University of Idlib to form a team called We Can. Members share their work and discuss it with colleagues. Everyone is encouraged to apply needed modifications or corrections.

“Employers always ask for no less than three years of experience to hire applicants to a job opportunity. But young people cannot have this experience without working,” Yazan Baya’, a graduate of the Technical Institute, told Enab Baladi.

Student teams and their training projects lie in the interest of students and equip them for the labor market, even when a training does not correspond to the academic content, said Yazan, also a member of Khutwa Team. “Learning a new language is one of the most important qualifications that students need to have today.”

Can students be teachers?

Ahmed Haj Ibrahim, a medicine student at the University of Idlib, does not mind receiving training from his colleagues. “Training is useful on the personal level. It enables trainees to acquire new skills and expertise,” he told Enab Baladi, adding that what matters is serious commitment on the part of students, as recipients, and trainers.

Ahmed appreciates all training opportunities, related to university education, or not, such as communication; human development; literature; languages and arts, suggesting that a student meeting must be held to present ideas and identify training needs.

“Students cannot teach students,” according to Dr. Muhammad al-Omar, a professor of pediatrics at the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Idlib, because an academic approach should underpin education.

Al-Omar said that only a degree qualifies teachers.

As the faculty’s former dean, al-Omar added that language courses and other complementary activities that the university offers are “sufficient.”

For his part, the president of the University of Idlib, Dr. Ahmed Abu Hajar, believes that student training initiatives deserve appreciation, because they help to refine the students’ personality; make them feel socially included; teaches them to share and cooperate, he told Enab Baladi.

Abu Hajar denied the claim that the student-run training programs address issues neglected by the university, stressing that they would be particularly beneficial for students who miss classes due to long working hours.