Enab Baladi – Aleppo Countryside

in order to adopt the best option, Tasneem Kanju, a high school student from Azaz city, has decided to avoid problems she might face during her university enrollment. Thus, she chose to take her final exams in the Turkish method. Students in the northern countryside of Aleppo find it difficult to determine the

Tasneem chose not to trouble herself by taking two different exams, and attributed that to the region’s circumstances, based on what she told Enab Baladi, in addition to the problems students have encountered last years, as they were asked to seal their Turkish certificates to be admitted into the University of “Aleppo.”

One curriculum with two different certificates

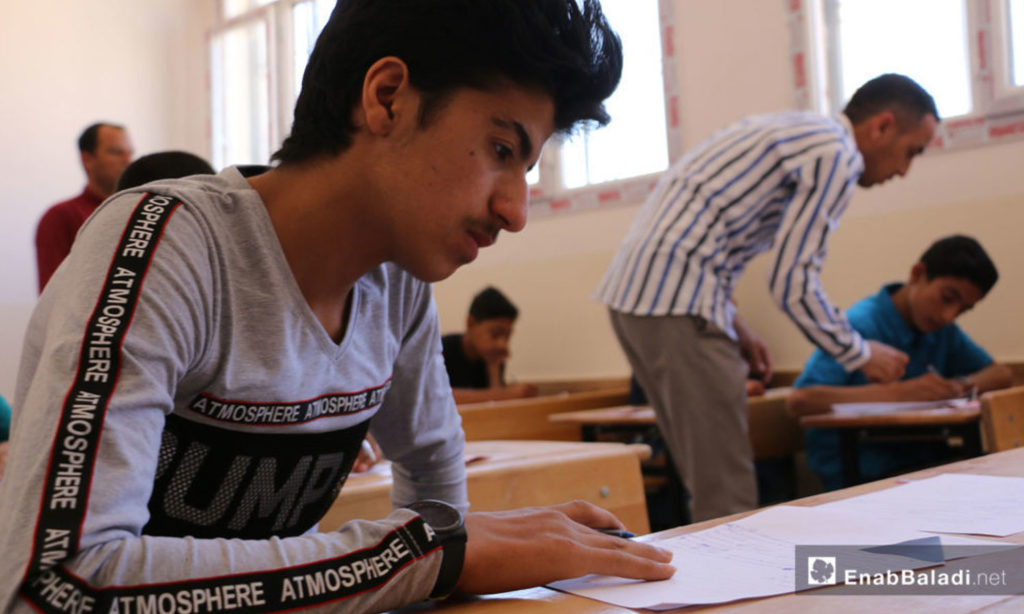

Taking the first secondary school examination in the northern countryside of Aleppo is done through an automated Turkish system which lasts for six days, while its correction takes place in Turkey. Certificates obtained are recognized by Turkey and students are also allowed to apply for universities in opposition-held areas.

These automated exams are organized by the education directorates affiliated to the local councils along with the Turkish education directorates. For students to take these exams, they must have an identity card issued by the local councils and linked to the Turkish Civil Registration Department, provided that they are not more than 27 years old.

While, the system of the “Syrian interim government” (SIG), known as the “coalition system”, all exams are written and they last for twenty days. Meantime, the obtained certificates are recognized by many European countries, according the ministry of education, also students can use these certificates to gain admission to universities in opposition-held areas.

Turkish exam “easier” and the Syrian “fairer”

Tasneem preferred the Turkish automated system because it is hard to memorize all study materials, since “SIG” exams are longer and require more details and explanations in their answers taking into account that she is a student of literature.

As per grades, Tasneem said that written exams are more “tolerant”, since their marks are broken down based on the provided answers, while the Turkish ones are easier but you might end up losing more marks if you missed the right answers.

Baker al-Saqqa, another student from al-Bab city, chose to take the automated exam, because it suits him better being a student of literature, also “the automated questions provide suggestions which makes it easier for students to recall answers”

However, automated exams are harder compared to written ones, especially for students whose major is science, because in written exams they have the chance to make more grade, according to Baker. He proceeded by explaining, in the automated system, an error in calculation means losing the whole mark for science students, unlike in the written one in which they obtain marks only by writing the solution.

Education professionals prefer written exams

The number of students who will sit for the final secondary school exam and whose names are registered in the education directorates affiliated to “SIG” amounted to more than eight thousand students according to the minister of education, Houda al-Abssi. Meantime the ministry adopts the written system.

Most of education professionals object the use of automated systems because they do not fully examine students and do not provide accurate assessments, while they rely heavily on guesswork and memory.

According to a female instructor (who refused to disclose her name for personal reasons), through automated systems, students can take more than one study material per day; however, the process of correction does not require expertise and staff.

While written exams focus is on the students’ ability to memorize and recall information they have studied and they rely on summaries and private lessons.

Although written exams require long periods of study, the ministry grants suitable preparation periods. The instructor added that several factors are taken int account during the correction process, which is not the case in the correction of automated exams.

Asim Melhem, Enab Baladi’s correspondent, contributed in the preparation of this article