Enab Baladi’s investigation team

Dia Odeh- Mohamed Homs- Nour Dalati

For an unknown reason, Syrian security forces arrested Wissam al-Tair, founder and director of the news website and page Dimashq Now, last December, after a security patrol raided an office where al-Tair was with Sham FM correspondent, Sonel Ali, and seized their equipment.

News about al-Tair’s arrest came as a shock as the founder of Dimashq Now was known for publicizing the Syrian regime’s propaganda as part of a process of psychological preparation ahead of launching a military campaign in Eastern Ghouta, on 18 February, in addition to coordinating between elements of the opposition, who are willing to be integrated in the reconciliation accord, and al-Assad forces and Russia.

Activists said that the reason behind al-Tair’s arrest was his cooperation with the international media. Others considered his frequent criticism of the regime’s officials to be the cause. Thus, al-Tair was supposed to be immune from such fate as has been honored by Asma al-Assad, in addition to being the first journalist to cover the news of the regime’s forces and having good relations with the regime’s officers.

After al-Tair’s arrest, publications and news broadcast have been shut down in Dimashq Now for two weeks, before resuming the website’s activities without referring to any kind of news about its founder till this moment.

Al-Tair is not the only media figure to meet this fate despite being loyal to the regime, as news about journalists and media professionals being harassed in areas under the regime’s control have been circulating lately.

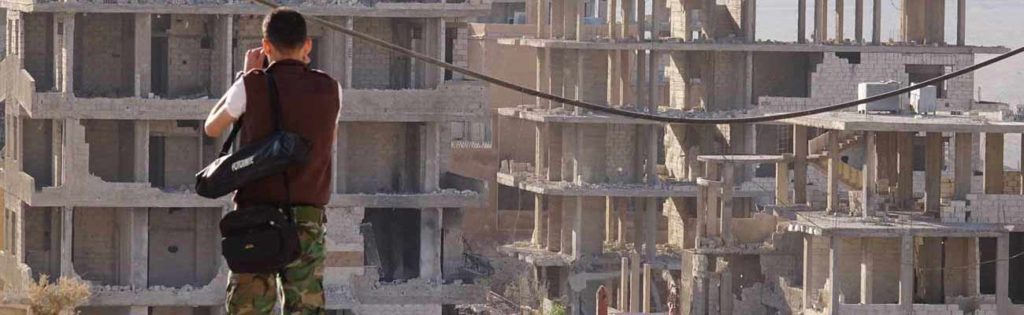

Journalist photographing wreckage of a destroyed building at the Scientific Studies and Research Center in Barza, north of Damascus – 2018 (AFP)

In the grip of security forces: Harassment is the predominant practice

Prior to al-Tair’s arrest, three local media journalists have been also detained. Local news website Hashtag Syria reported that journalist Amer Daru, who worked for several Lebanese media outlets, was arrested last August following orders issued by a “high-ranking party official.”

The Syrian regime’s security branches arrested Ihab Awad and Rola al-Saadi, two of Hashtag Syria’s journalists, following the confusion caused by the decision to hold a “special session” of university examinations, last summer. Hence, both journalists were taken into custody after subjugating them to physical search and inspecting their cameras in order to make sure they did not contain any footage or videos of the Umayyad Square.

The local news website Snack Syrian indicated that the journalists were detained in the Umayyad Square, where a students’ sit-in was supposed to take place demanding the government to issue a decision to hold a “supplementary examination session.” The website noted that the arrest was conducted “by a security agency and not by the Ministry of the Interior, although the detainees were Journalists and civilians.”

Cybercrime

Most of the arrests against local journalists, which may go on in the future, are part of the Cyber Crime Act, which was issued under the Electronic Media Law No. 26 of 2011, to regulate communication with the public via networks, media and publishing regulations, before issuing the latest legislation on cyber crimes in Decree No. 17 of 2012.

Most of the charges against some journalists or media figures are included in the article “Public defamation of public personalities through social media platforms” or “Infringement of their privacy by publishing information, even if it is true.” This is exactly what happened to the journalist Rafiq Salameh, who was arrested last April and released early May.

Salameh, who works for several media outlets, including Al-Alam News Network, war media, the Qatari Command and the Baath party branch in Homs, said on his Facebook page that the charges against him were based on the suspicion of having a Facebook page and “posting offensive comments against the Minister of Health,” pointing out that there is no evidence or proof of these charges.

In another incident, the Syrian security services arrested the director of Hashtag Syria, Mohammed Hersho, in April, after publishing news about the government’s intention to increase the price of gasoline, amid the acute fuel crisis that hit the country. The Syrian Ministry of Petroleum and Mineral Resources launched a campaign against the news website and accused its founder of disseminating misleading news that caused overcrowding in gas stations.

The Syrian regime released Hersho following the issuance of a brief statement and apology on the website, explaining that the news reported earlier about the increase of fuel prices is “understudy” and no official decision was taken yet.

Media, whose sin?

Hersho returned to the spot light of local media following news about shutting down his newspaper al-Ayam, after nearly two and a half years of its launch.

The newspaper published in its last issue, issue No 115, a final farewell to its readers, and wrote on the cover in red “Whose sin caused Syrian media to end up in this condition?

The chief editor of the newspaper, Ali Hassoun, announced a few days later that he would retire from journalism. He wrote an article in the editorial section of the last issue, entitled A Warrior’s Break, in which he considered the current stage to be “the harshest” in the history of the Syrian press due to escalating restrictions on the freedom of press, as “the rule of fear is now in control of journalists’ pens.”

Hassoun spoke about the accumulation of a culture of fear that has been handed down by generations of media workers in Syria, forcing most journalists to put their pens under “house arrest.” Journalists can be subjugated to arrest at any moment, as each one of them is guilty until his innocence is proven.

Hassoun indicated in his retirement statement that it became a sort of “insanity” to work in the field of journalism at the current stage, given that Syrian journalists are being harassed and pressed by powerful and influence people.

One symphony: The illusion of freedom is ephemeral

The status of media and press in Syria has not changed since the Baath Party took power in 1963 until today, as it did not depart from the orchestrated symphony that Information Minister under the reign of Hafez al-Assad, Ahmed Iskandar, referred to saying “the Syrian media is like a symphony orchestra led by a Maestro, who is the Minister of Information, and all the musicians look at the stick that he carries and play according to its movement.”

With the rise of the Baath Party to power, a state of emergency was declared and martial laws were issued, suspending the licenses of newspapers and publishing houses. Newspapers were closed; printing houses and tools were confiscated. The media policy in Syria was fixed at that time in accordance with the party’s principles and state policy, until the publication law was issued in 2001, which gave the right to establish private media outlets for the first time in decades.

The Publications Law No. 50 of 2001 gave the executive authorities the full right to intervene without permission in the movement and means of media activity, and established the principle of employing press and media to spread ideas of the ruling class, as a step to ensure their control of public opinion.

Al-Dumari was the first independent newspaper which experimented with the new media law, as Syria did not have private newspapers or magazines before. However, the Syrian government quickly started oppressing the newspaper in 2003 until it forced its founder to shut it down. Journalists and politicians were pursued again, as many of them were arrested in 2005. Thus, the authorities’ oppressive practices reflected the position of Bashar al-Assad’s government regarding all types of independent private media that manage to escape the orbit of state media.

A four-year boom

Ten years have passed since the issuance of the new Publications Law, when Syrian President Bashar al-Assad issued Media Law No. 108 of 2011, which coincided with the start of the Syrian revolution and the outbreak of peaceful protests in several Syrian governorates. The social unrest was accompanied by the emergence of many Syrian journalists and activists who covered the demonstrations, posted on the Internet and reported the revolution news to Arab and foreign media, in an unprecedented scene in Syria.

The Media Law 2011 provided for the establishment of the so-called National Media Council, which is aimed at drawing the state’s media policy and issuing licenses for private media outlets. On the other hand, the National Media Council was granted the authority to accredit Arab, foreign or Syrian correspondents working for foreign media.

In an interview with Enab Baladi, a Syrian journalist in Damascus, who preferred to remain anonymous, declared that the formation of the Council in 2011 was meant to reform and develop Syrian media. However, the Council did not make any contribution due to the dominance of the Syrian regime and the story intelligence has imposed on the media.

The journalist revealed that the main objective behind the formation of the Council is conveying to the whole world that Syrian media is free and supervised by private and public sectors experts. However, it was not successful and couldn’t go on for Bashar al-Assad issued a decree on August abolishing the Council because of the lack of integration between its work and the Ministry of Information’s.

Between 2011 and 2016, Syria’s media coverage was at its peak having local newspapers, networks and websites, which the Syrian regime has allowed to operate in its held areas and battlefields, in the forefront. Hundreds of news pages appeared on social media sites with names in areas covering the news of these regions. Despite their focus on the service and living conditions, they did not exceed the permissible limit in Syria, without tackling political issues or matters that could constitute a breach in the structure of the system.

The Syrian regime sought to grant its loyal journalists and activists enough freedom of expression through enacting the Media Law of 2011, which sets for the creation of the National Media Council. This move was meant to support its propaganda through promoting the concept of “war on terror” and portraying the Syrian revolution as a conspiracy against the country and National security.

The dissolution of the National Media Council in 2016 was no coincidence, but rather occurred at a time when the Syrian regime was about to restore the areas it has lost. The regime felt threatened by the same media professionals it has advocated for four years ago, because they managed to attract large audience and started to criticize and express their opinion; thus crossing the lines they were allowed to work within.

Weapons in the battlefield

After 2011, media shifted focus to greater platforms amid social media overflow. For example, print newspapers could no longer support or deliver an idea, unlike electronic media. After the revolution broke in 2011, activists and field journalists worked on the ground to enhance the role of citizen journalism.

The proliferation of such kind of journalism, and the extent to which it was professional and influential in some cases, made al-Assad’s official media unable to keep up with this phenomenon. Hence, he recognized the need to be present on social media websites, which have overshadowed traditional media in terms of the number of followers.

Journalist and human rights activist Mansour al-Omari said that the beginning of Syrian regime activity on social media platform was marked by establishing centers belonging to the security forces that monitor publications and accounts related to specific events, publish propaganda, and hack the e-newspapers and accounts of activists and others.

Al-Assad allowed for the establishment of news accounts on social media, being supervised by intelligence. Al-Omari also suggested that these accounts were meant to confront opposition news pages, independent news websites and media activists accounts, and publish fabricated news as part of psychological warfare, in addition to disinformation and publishing the regime’s account of events in social media. Their aim was attracting the largest number of followers.

Al-Omari added that al-Assad considers media as another field for the ongoing battles. But with the growing number of pro-regime media activists and pages criticizing the government, he felt threatened by the proliferation of criticism and was afraid that the restrictions through which he was governing the Syrian media would break loose. He issued several decrees to tighten his grip even on people’s publications on Facebook and elsewhere.

“They believed they became free journalists”

Despite the great deal of attention, some journalists and media activists have acquired in Syrian-held areas over the past years, they could not enjoy enough freedom to act and express their opinion. The Syrian regime’s harassment which started in mid-2018 has indicated that it was selling them “press freedom illusion” to promote for the ideas it wanted to convey since the first months of the Syrian revolution.

The Syrian regime tried to trick people into believing that it had won the battle against the opposition factions and showed the progress it had made on the ground by allowing specific media professionals and networks to enter the battlefield to cover its “victories.”

The efforts of media professionals and networks were not qualitative, for the regime was in control of the information disseminated to the public and the target groups. It has relied on specific key figures, such as the correspondent of Russia Today TV Channel, Iyad al-Hussein, the manager of Dimashq Now page Wissam al-Tair.

The Syrian regime chose specific media key figures to play a specific role and allowed them to enter the areas where the population has been displaced,” said Mohammad al-Abdullah, Executive Director of Syria Justice & Accountability Center, in an interview with Enab Baladi

But later on, the situation has changed and the journalists the regime has promoted for ended up having many followers and a large audience and becoming influential. The Syrian regime rejected this and worked to overcome it, in conjunction with the deterioration of services and supplies, including the high prices of food and fuel.

According to al-Abdullah, the journalists thought they were influential. “They believed they became real journalists capable of criticizing.” Public pressure and opinion played an important role pushing them to talk about poor services.

Journalists tried to take advantage of the fame they gained, as well as playing the “support” card, being so close to senior officials, and having access to all areas, especially during military operations.

Around the regime’s orbit

The regime rejected the new role of journalists “because they exceeded the limit, and went on mobilizing people against deteriorating services, in addition to the emergence of their critical voice in the country,” according to al-Abdullah.

He believed that the regime made use of these figures to convey certain messages but this does not grant them the right to criticize it. Therefore, the regime had to arrest them albeit for a limited period of time.

Although the arrests of journalists in regime-held areas were few, they communicated its true doctrine conveying a certain message to these journalists saying: “If you want to work with us being part of our media, then we won’t I will let you express your own opinion.”

According to the Executive Director of Syria Justice & Accountability Center, “the Syrian regime will not allow the emergence of an independent media that is not directly linked to its security services.

In the same vein, journalist and human rights activist Mansour al-Omari said that media propaganda is one of the main pillars of dictatorial regimes, which succeed in controlling the media only by suppressing any other that may present a threat to the official version.

If the security grip imposed on the media is loosened, the pillars of these regimes will become weaker and their corruption and criminality will be exposed. Al-Assad’s regime being perfectly aware may allow some of these journalists to say something, but after killing and displacing more than half of the Syrian people in order to maintain its position, it won’t pave the way willingly to media freedom. It would rather tighten its grip and keep pace with technological developments to achieve this.

Despite declared loyalty:

The tightening is threatening media training centers

Any Syrian who holds a university degree and has media experience can launch a media training center, according to the official website of the Syrian E-Government Portal , precisely the Permits Department of the Ministry of Information.

The active centers are supposed to “practice vocational training in a modern and useful manner for the trainees, and help them to upgrade professional level to practice modern media.” These are the conditions for obtaining permits, provided that “the fees charged by the center are reasonable and appropriate for the Syrian economic situation.” Attendees must have good academic and cultural level and have at least a high school diploma.

On the other hand, the response to the possibility of acquiring a permit was not very remarkable, which is based on the provisions of the Syrian Media Law promulgated in Legislative Decree No. 108 of 2011 and its amendments of 2016, as few institutes are often active in organizing media training sessions in the city of Damascus, or in other governorates on a smaller scale.

Training sessions under Baath Party’s auspices

Despite the increase of the number of media outlets in the regime-controlled areas during the past few years, there have been no qualified staffs in return. This is due to the lack of media experts or students inside Syria. As a result, some media training centers have been established, most of which in the city of Damascus.

Enab Baladi has monitored the activities of three centers that regularly organize media training sessions in Damascus and promote these sessions through Facebook, namely the Middle East Center for Media Training, the Young Journalists Club (YJC) and Media Preparation Institute of the Ministry of Information. Whereas, other centers provide various training sessions in photography, correspondence and radio broadcasting.

Some of the teachers of the Faculty of Media work in these schools, along with two Syrian TV channel employees and Lebanese as well as Iranian trainers.

The pages of these centers reflect the nature of their political loyalty. The YJC is run by Raeda Waqaf, known for her pro-regime positions, who ran the government TV channel Syria Drama, while Iranian director Mohammad Reza Abbasian participates with her in some of the training sessions.

Moreover, images of the head of the regime, Bashar al-Assad, are hanged on the walls of the training rooms of the Media Preparation Institute.

Adding to that, the Baath Party regularly organizes training sessions in the governorates, often provided by the teacher at the Faculty of Media, Ahmad al-Sha’rawi, which in turn graduate dozens of affiliates.

The Syrian regime prohibits the holding of training sessions in the field of media, except with the prior approval of its Ministry of Information, unless the training center is licensed.

A circular issued by the Prime Minister of the Government of the Syrian regime, Imad Khamis, in 2017, has prevented the organization of training dialogues in the form of paid media training courses, in response to the holding of training sessions, especially by the correspondents of pro-regime agencies and TV channels, including a training course for the correspondent of radio station Sham FM, Sumer Hatem, in the cities of Latakia and Tartus.

Faculty of Media attacks training centers: No more licenses

While some of the teachers of the Faculty of Media participate in the work of private training centers, the Dean of the Faculty, Mohammed al-Omar, and his deputy, Nahla Issa, known for their loyalty to the Syrian regime, have attacked these centers.

Al-Omar said in statements to local newspaper al-Watan in May that the media training centers in Syria are “media shops” that are only aimed at earning profits. He added that the training center does not have the legal and professional right to grant the title of a journalist to the trainee.

Al-Omar called on the Ministry of Information and the Syrian Journalists Union to put an end to this “buffoonery,” pointing out that there are talks about the work on limiting the number of these unlicensed centers and holding them accountable. He explained that no license has recently been granted to any training center.

Nahla Issa considered, during the same interview with al-Watan, that those who undergo these training sessions do not hold secondary education diplomas, and “obtain certificates that delude them that they are legally qualified because they are signed by the Syrian Journalists Union and the Ministry of Information.”

Issa justified this saying that the media profession has become “profaned” and “a profession to those who did not find a job.” The evidence to this, according to her, is “the fact that there are hundreds of people on social media websites who claim to have the title of a journalist while they do not hold high school diplomas.”

Conventional patterns and hate speech: Media “straying away from its path”

The number of media outlets in the regime-controlled areas has increased in recent years, under the influence of the new media trends that have followed the issuance of the 2011 Media Law, which encouraged the licensing of new newspapers, news websites and radio stations.

Although this media outlets boom has been accompanied by a similar boom in the Syrian opposition areas, Kurdish forces regions, or even outside Syria, the circumstances under which these outlets have been governed, the nature of security control and the legal framework have not provided an appropriate opportunity for them to achieve professional development. These professional development efforts have rather remained subject to security concerns.

As a result, journalists who have aspired to open up to media concepts, such as breaking stereotypes in journalism, using media to serve the citizens, avoiding hate speech, or achieving advanced levels of freedom of expression, have been frustrated. Those who work in this field have, thus, been forced to conduct their profession in a way that keeps them safe from accountability or detention.

Identical forms

News forms are prevailing in most of the press production of the regime’s media outlets, especially in emerging or relatively recent websites, such as Hashtag Syria, Sham Times News Agency and Syrian Snack website.

Through monitoring the daily production of these websites, it can be noted that most of the topics that are dealt with are local and miscellaneous mostly in the form of news or reports.

Most of these outlets deviate away from deep investigations, which are based on disclosure, accountability and access to the greatest amount of information, for which the journalist or institution may pay a high cost.

For example, al-Ayam newspaper has been prominent as an active part in the production of deep investigations inside Syria over the past two years, but has faced repeated tightening. The regime prevented the release of one of its editions in October, before being closed in May following the arrest of its owner, Mohammad Hersho.

On the other hand, government and pro-regime TV channels have increasingly become directed towards arts and entertainment programs, at the expense of social or local service programs. For example, for the first time, three Syrian actors have been presenting simultaneous contest programs. The first is “Cash with the Stars” presented by Shokran Mortga and Bassem Yakhour on Lana TV, and the other is Sfar Ktar presented by Ayman Reda on Syria TV.

War correspondent Raeif al-Salameh on the front of al-Qaryatayn in the countryside of Homs – 2017 (Raeif al-Salameh)

Highest rate of “hate speech”

The official pro-regime Syrian media is using hate speech more than the opposition media or that active in the areas controlled by the Kurdish forces, according to a study by the Syrian Center for Media and Freedom of Expression, entitled “Hate speech in the Syrian Media” and published in March.

The average use of hate speech by media that defend the regime’s point of view reaches 27.4 percent, the study said.

The study justified this by the fact that the centrality of the decision and the extent to which the discourse adopted by media outlets is unified are important factors in determining the rate of hate speech.

The study added that these outlets, whether governmental or private, follow “a central authority represented by the Ministry of Information and then the security authorities, which makes their editorial policy unified and well-studied towards the promotion of the Syrian regime’s political discourse.”

“Under the military”: The future is similar to the present

Media professional and scenarist Hafez Qarqout does not see a difference between the form of media work in the late twentieth century and its present reality. “Al-Assad’s regime has deliberately worked on controlling all key institutions and linking them to the Republican Palace, which has run everything in the country, including the media, which these regimes consider a sensitive institution that can reach the public and agitate it. The regime has thus developed a plan to control all aspects of the media,” He clarified.

Qarqout considers that there is a link between the security’s management of aspects of society and “the absence of a mature media situation in Syria,” which is widely evident in the current scene that is dominated by the security authorities and the prevailing military situation in the country.

“The intervention of the security forces in the media situation has led to the weakening of energies, displacement of staffs and the arrest and imprisonment of others,” according to Qarqout, who believes that once these young staffs have gotten out of the regime’s control, they have started presenting skillful messages to the world, indicating that “the security tightening had been like a nightmare to all aspects of life and to the media sector.”

Qarqout agrees on this point with journalist and human rights activist Mansour al-Omari, who also stressed that the liberation of media from the security grip undoubtedly does not serve the Syrian regime’s interests.

In the light of this, it can be said that any future of the Syrian media under the regime’s control cannot be auspicious. This is because, under the security’s grip, the media will not enjoy any real margins of freedom of expression or the development of the content and form of media messages.