“We swallow the bitter pill and pray to God,” these words are repeated by dozens of Deir ez-Zor governorate’s employees, who after being displace, have worked in the other governorates’ institutions and directorates. Today, however, they are forced to return following the latest decisions of the Syrian regime’s government, which cancelled Deir ez-Zor employees’, both temporary and permanent, contracts with the institutions in the cities which they have moved to years ago.

The regime took control over the whole city of Deir ez-Zor, the last part of which was al-Hamidiyeh neighborhood, early in November 2017, and gradually announced the reactivation of services and institutions.

The government’s decision triggered a state of indignation among the people of Deir ez-Zor, who expressed their inability to challenge the decisions scared for their lives and their families’ livelihoods according to a number of the people who left the city due to the siege and the shutdown of the governmental institutions in the areas that went out of the regime’s control in favor of the “Islamic State” (IS) group.

A State of Loss and Over Thinking

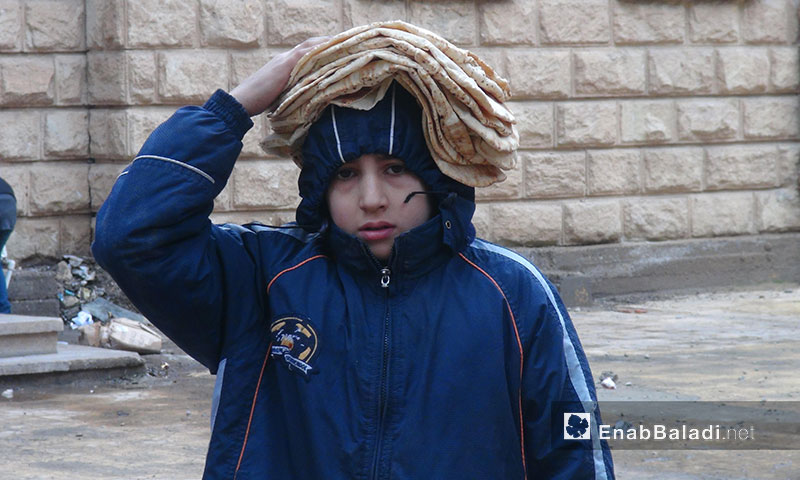

Activists estimate that about 80% of Deir ez-Zor is destroyed, despite the fact that the regime has announced the start of rehabilitating the city and that it deems the neighborhoods of al- Jorah and al- Qosoor in the city’s western part, as well as

Harabesh neighborhood as the less damaged.

Um Mohammad (39 years) says that the directorate under which she works in al-Hasakah has notified her that her salary would stop and that she has not yet made up her mind on going to her work in Deir ez-Zor to earn money.

Um Mohammad worked in al-Hasakah for six years after being displaced from the eastern countryside of Deir ez-Zor, pointing out that she experienced a state of stability in the past a few years; she adds: “I feel like a puppet who is being moved according to decrees that do not show concern for the employees or their exceptional conditions […] Nevertheless, we are forced to listen and obey so our salaries would not stop.”

After the death of her husband, a few years ago, she became responsible for her family and earning money to afford a life for her four children, pointing out that, currently, she has no relatives in Deir ez-Zor.

She wonders: “Where to should I take my family while everyone knows that the condition in the city is unstable. In addition to this, my children have been used to living here and its difficult for them to return to a semi-destroyed city.”

Um Mohammad observes her furniture, in al-Hasakah, and sighing, says: “How would we move all this while we are unable to find a means to transport us. If we sold this, how would we be able to buy new one in the shadow of the high prices?”

“No one would hear our screams or feel our pain,” says Abu Jasem (53 years), the displaced employee from Deir ez-Zor, who earns money for two families. He received a notification informing him of his need to return to work in the city, adding that the rising rentals and the decreasing income would not help him live upon moving to Deir ez-Zor.

According to the employee, who used to own a three-story house that has been totally destroyed due to bombardment, the return of thousands of employees would create a housing crisis and increase rentals, considering that living in Deir ez-Zor will be “impossible under the current situation.”

“The one who issued the decree should have thought of rehabilitating the city first,” according to Abu Jasem, who says that “transportation means to Deir ez-Zor are scares and costly. Additionally, there is no transportation within the city […] The city’s infrastructure is almost destroyed and cannot accommodate a massive number of people.”

Another Crisis

In a survey conducted by Enab Baladi, people from the al- Jorah neighborhood questioned the capacity of the neighborhood and whether it would be able to accommodate new families under its current condition, the one they described as “appalling,” stressing that the city is suffering from the absence of water and electricity, in addition to the spread of rubbles in some of its streets.

According to activists, the regime created another crisis to be added to the many problems which the city and its people are suffering from. Nonetheless, a small segment, including Abu Hussain (49 years) who owns a small shop in the city, believe that this decision is “a chance to reactivate the markets and to end the real estate market’s stagnation.”

Dozens of the city’s houses are empty and fit for habitation, according to Abu Hussain, who considers that “everyone should participate in empowering Deir ez-Zor and giving it its life back,” admitting that this “demands capabilities that exceed the individuals’ capacity.”

The employees’ influx to the city will create a “fierce competition” between people for limited resources, according to Deir ez-Zor’s activists, indicating “a state of social revulsion between the displaced people who left the city and the people who stayed there.”

According to civil organizations estimates, the return to the city starts with clearing the rubble off and creating suitable conditions for about 150 thousand civilians who live in its neighborhoods.

Some of Deir ez-Zor’s people admit that employees are forced to live with the consequences of the governmental decision, “because the regime is used to place undue strain on employees,” considering that their voices “would not be heard, for some of the objections have been met with security threats and warnings, which might place them under penalties that could reach the point of dismissal.”